Mysterious results in an experiment may be due to dark energy

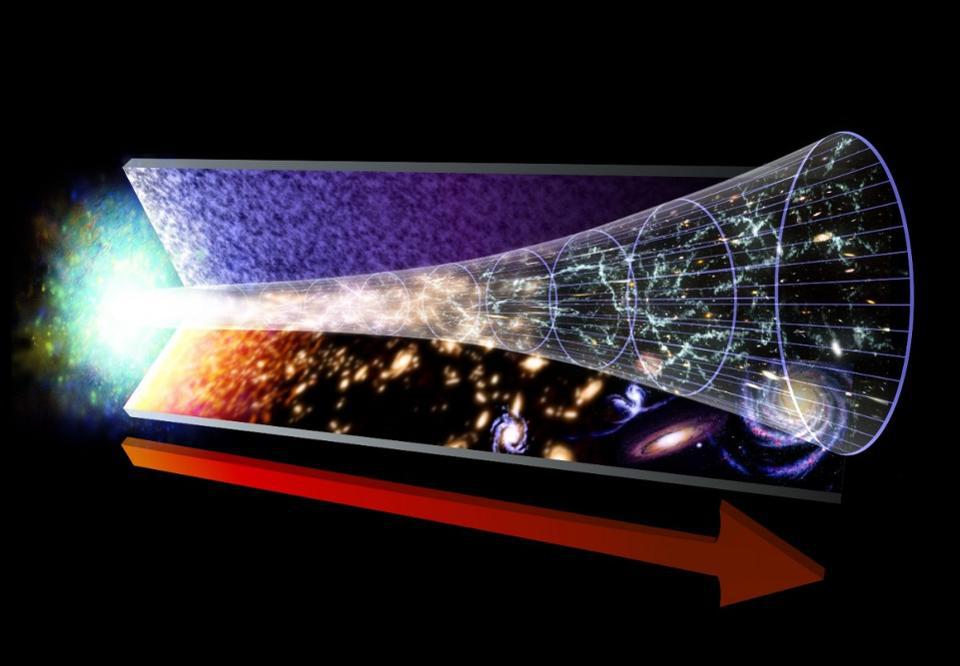

One of the most mysterious subjects that scientists around the world are studying is called dark energy. Scientists believe dark energy is the mysterious force that leads to acceleration in the universe. A team of researchers from the University of Cambridge has published a study that suggests unexplained results obtained from an experiment conducted in Italy called XENON1T could have been caused by dark energy.

Interestingly, the experiment was designed to detect dark matter, but Cambridge scientists believe dark energy could account for the mysterious and unexplained results from the experiment. In the study, physical models were constructed in an attempt to explain the experiment results. Study researchers believe the experiment results could have been caused by dark energy particles in a region of the sun dominated by strong magnetic fields.

Unfortunately, additional experiments will be required to confirm their theory. Nevertheless, scientists are excited at the possibility of the discovery of dark energy. Currently, estimates predict that everything we can see with our eyes in the universe accounts for less than five percent of what’s there. Most of the material in the universe is dark, and theories suggest 27 percent of the entire universe is dark matter.

Dark matter is described as a force that holds galaxies and the cosmos itself together. Scientists also believe that 68 percent of the universe is made up of dark energy causing the universe to expand and accelerate. Since both dark matter and dark energy are invisible, little is known about them.

The presence of dark matter was first theorized in the 1920s, but dark energy wasn’t discovered until 1998. Scientists say that while the experiment was intended to detect dark matter, detecting dark energy is even more difficult. The study comes after the XEON1T experiment discovered an unexpected signal about a year ago that was higher than the expected background. Researchers on this study decided to explore a model where the unexpected signal was attributed to dark energy rather than dark matter. Scientists admit they are still far from understanding dark energy, and additional experiments are needed.

Have we detected dark energy? Scientists say it's a possibility

A new study, led by researchers at the University of Cambridge and reported in the journal Physical Review D, suggests that some unexplained results from the XENON1T experiment in Italy may have been caused by dark energy, and not the dark matter the experiment was designed to detect.

They constructed a physical model to help explain the results, which may have originated from dark energy particles produced in a region of the Sun with strong magnetic fields, although future experiments will be required to confirm this explanation. The researchers say their study could be an important step toward the direct detection of dark energy.

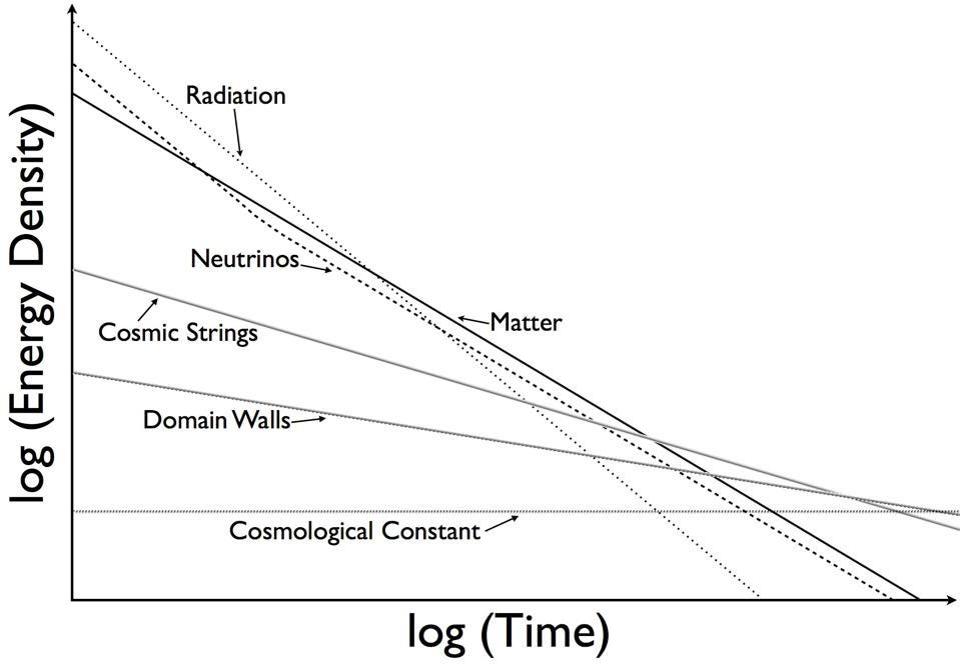

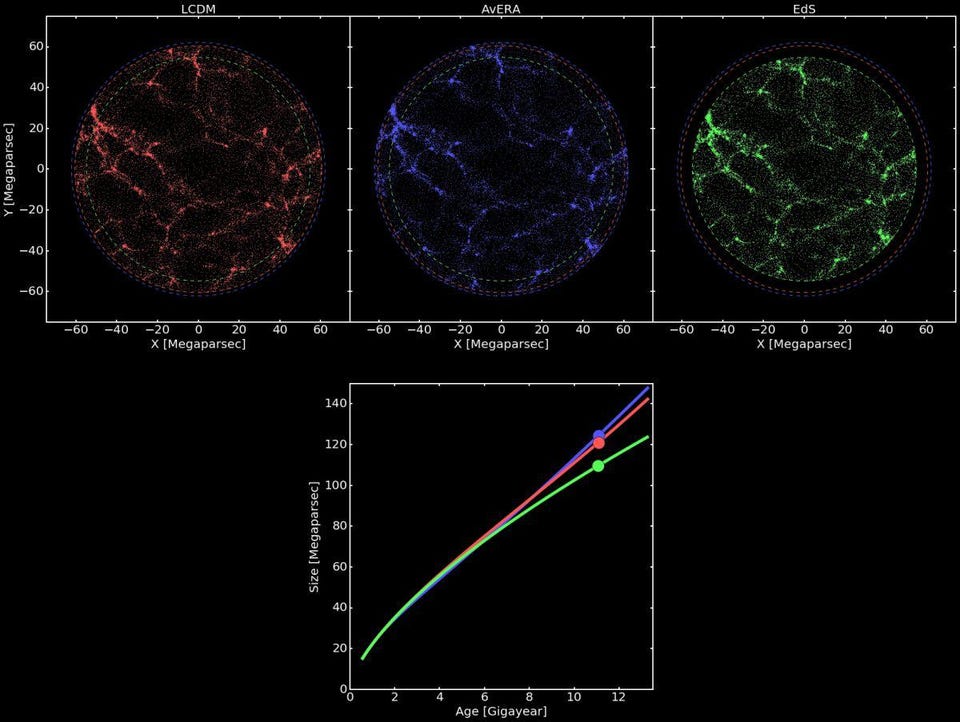

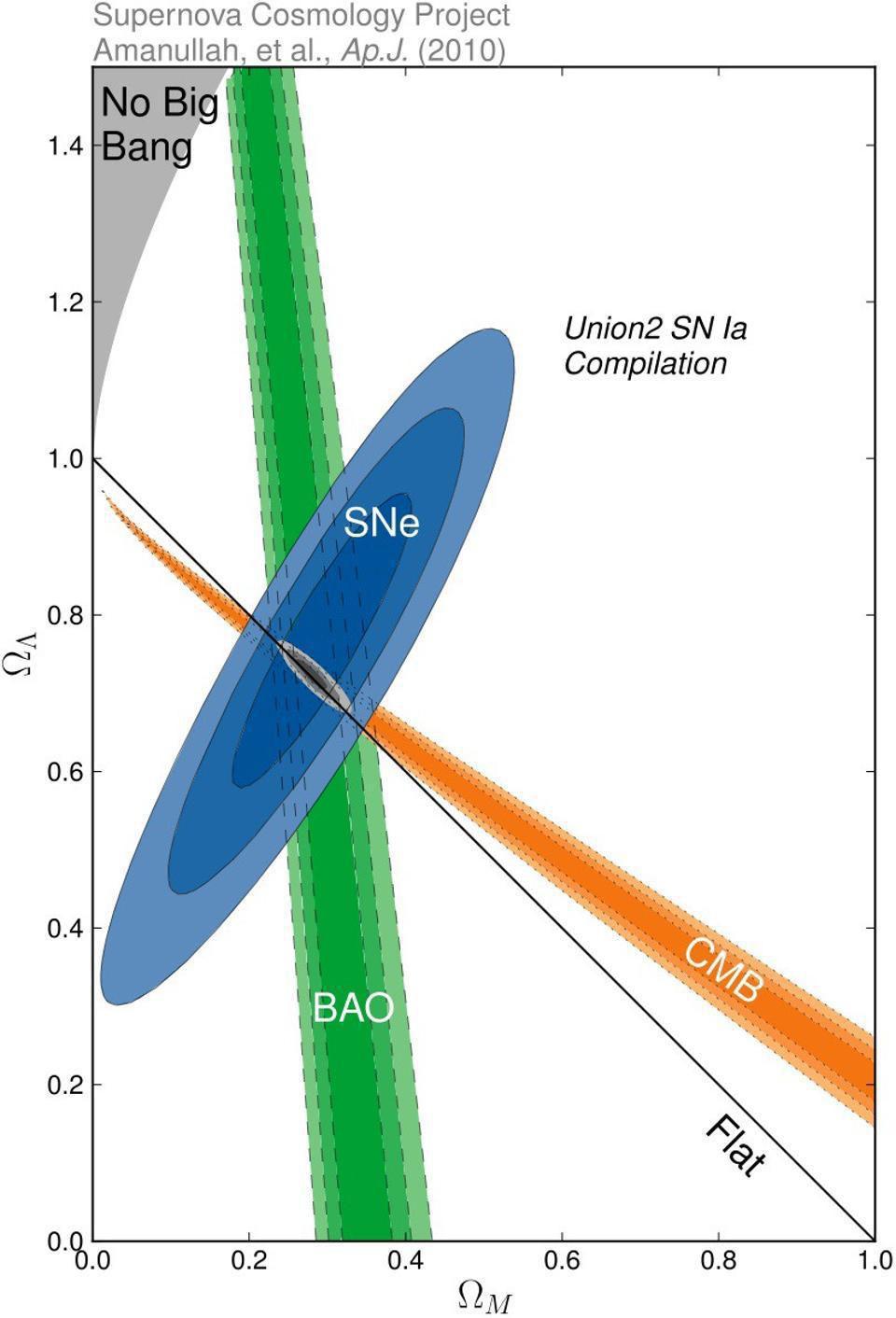

Everything our eyes can see in the skies and in our everyday world—from tiny moons to massive galaxies, from ants to blue whales—makes up less than five percent of the universe. The rest is dark. About 27% is dark matter—the invisible force holding galaxies and the cosmic web together—while 68% is dark energy, which causes the universe to expand at an accelerated rate.

"Despite both components being invisible, we know a lot more about dark matter, since its existence was suggested as early as the 1920s, while dark energy wasn't discovered until 1998," said Dr. Sunny Vagnozzi from Cambridge's Kavli Institute for Cosmology, the paper's first author. "Large-scale experiments like XENON1T have been designed to directly detect dark matter, by searching for signs of dark matter 'hitting' ordinary matter, but dark energy is even more elusive."

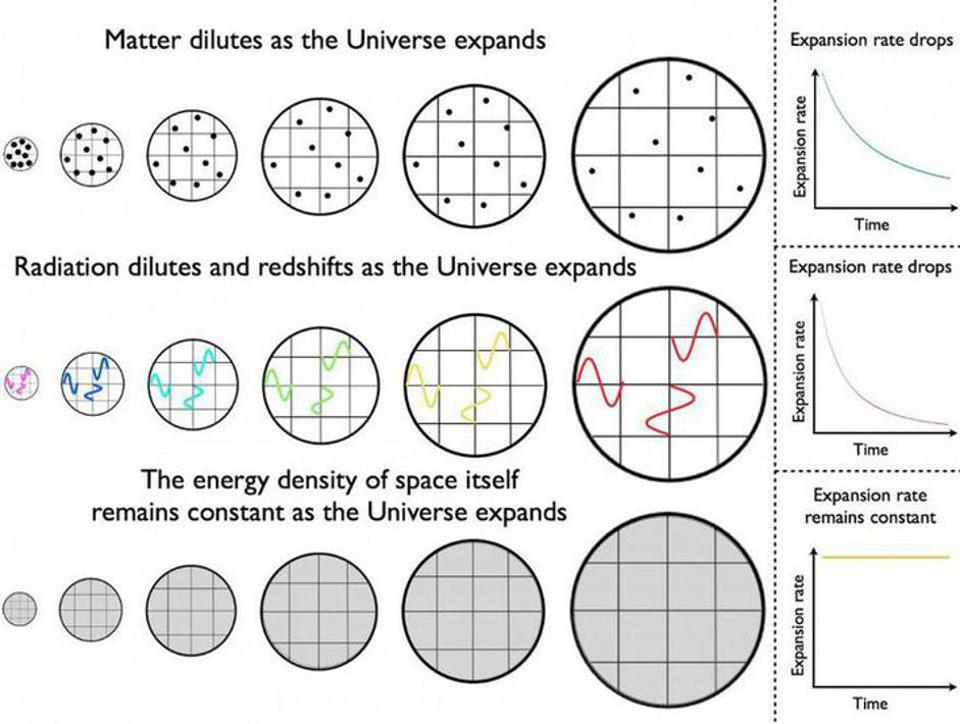

To detect dark energy, scientists generally look for gravitational interactions: the way gravity pulls objects around. And on the largest scales, the gravitational effect of dark energy is repulsive, pulling things away from each other and making the Universe's expansion accelerate.

About a year ago, the XENON1T experiment reported an unexpected signal, or excess, over the expected background. "These sorts of excesses are often flukes, but once in a while they can also lead to fundamental discoveries," said Dr. Luca Visinelli, a researcher at Frascati National Laboratories in Italy, a co-author of the study. "We explored a model in which this signal could be attributable to dark energy, rather than the dark matter the experiment was originally devised to detect."

At the time, the most popular explanation for the excess were axions—hypothetical, extremely light particles—produced in the Sun. However, this explanation does not stand up to observations, since the amount of axions that would be required to explain the XENON1T signal would drastically alter the evolution of stars much heavier than the Sun, in conflict with what we observe.

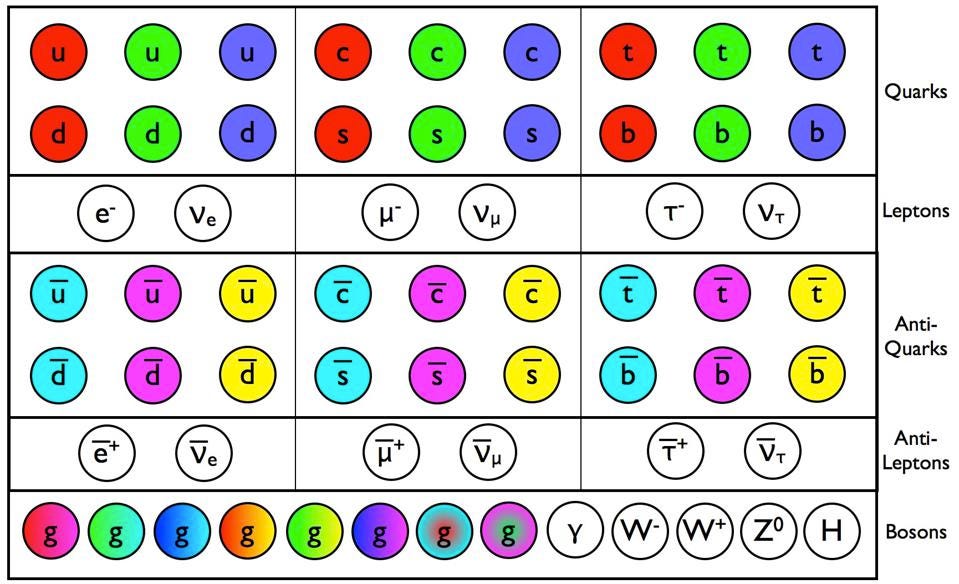

We are far from fully understanding what dark energy is, but most physical models for dark energy would lead to the existence of a so-called fifth force. There are four fundamental forces in the universe, and anything that can't be explained by one of these forces is sometimes referred to as the result of an unknown fifth force.

However, we know that Einstein's theory of gravity works extremely well in the local universe. Therefore, any fifth force associated to dark energy is unwanted and must be 'hidden' or 'screened' when it comes to small scales, and can only operate on the largest scales where Einstein's theory of gravity fails to explain the acceleration of the Universe. To hide the fifth force, many models for dark energy are equipped with so-called screening mechanisms, which dynamically hide the fifth force.

Vagnozzi and his co-authors constructed a physical model, which used a type of screening mechanism known as chameleon screening, to show that dark energy particles produced in the Sun's strong magnetic fields could explain the XENON1T excess.

"Our chameleon screening shuts down the production of dark energy particles in very dense objects, avoiding the problems faced by solar axions," said Vagnozzi. "It also allows us to decouple what happens in the local very dense Universe from what happens on the largest scales, where the density is extremely low."

The researchers used their model to show what would happen in the detector if the dark energy was produced in a particular region of the Sun, called the tachocline, where the magnetic fields are particularly strong.

"It was really surprising that this excess could in principle have been caused by dark energy rather than dark matter," said Vagnozzi. "When things click together like that, it's really special."

Their calculations suggest that experiments like XENON1T, which are designed to detect dark matter, could also be used to detect dark energy. However, the original excess still needs to be convincingly confirmed. "We first need to know that this wasn't simply a fluke," said Visinelli. "If XENON1T actually saw something, you'd expect to see a similar excess again in future experiments, but this time with a much stronger signal."

If the excess was the result of dark energy, upcoming upgrades to the XENON1T experiment, as well as experiments pursuing similar goals such as LUX-Zeplin and PandaX-xT, mean that it could be possible to directly detect dark energy within the next decade.

New study sows doubt about the composition of 70 percent of our universe

More information: Sunny Vagnozzi et al, Direct detection of dark energy: The XENON1T excess and future prospects, Physical Review D (2021). DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevD.104.063023

Journal information: Physical Review D

Provided by University of Cambridge

By

Isaac Schultz

Friday 3:03PM

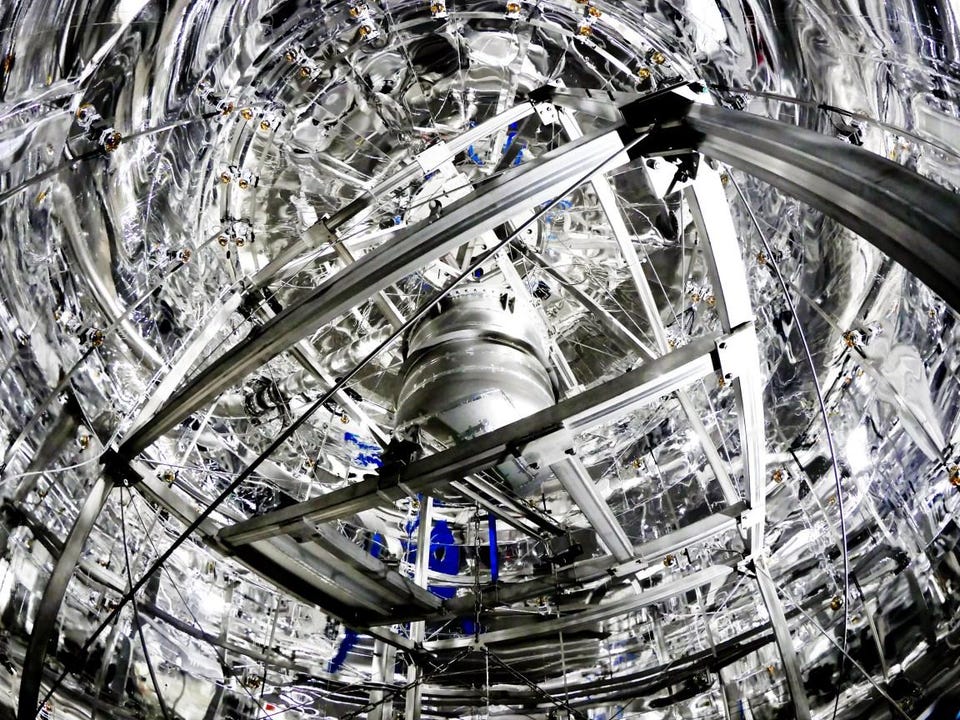

A team of physicists at the University of Cambridge suspects that dark energy may have muddled results from the XENON1T experiment, a series of underground vats of xenon that are being used to search for dark matter.

Dark matter and dark energy are two of the most discussed quandaries of contemporary physics. The two darks are placeholder names for mysterious somethings that seem to be affecting the behavior of the universe and the stuff in it. Dark matter refers to the seemingly invisible mass that only makes itself known through its gravitational effects. Dark energy refers to the as-yet unexplained reason for the universe’s accelerating expansion. Dark matter is thought to make up about 27% of the universe, while dark energy is 68%, according to NASA.

Physicists have some ideas to explain dark matter: axions, WIMPs, SIMPs, and primordial black holes, to name a few. But dark energy is a lot more enigmatic, and now a group of researchers working on XENON1T data says an unexpected excess of activity could be due to that unknown force, rather than any dark matter candidate. The team’s research was published this week in Physical Review D.

The XENON1T experiment, buried below Italy’s Apennine Mountains, is set up to be as far away from any noise as possible. It consists of vats of liquid xenon that will light up if interacted with by a passing particle. As previously reported by Gizmodo, in June 2020 the XENON1T team reported that the project was seeing more interactions than it ought to be under the Standard Model of physics, meaning that it could be detecting theorized subatomic particles like axions—or something could be screwy with the experiment.

“These sorts of excesses are often flukes, but once in a while they can also lead to fundamental discoveries,” said Luca Visinelli, a researcher at Frascati National Laboratories in Italy and a co-author of the study, in a University of Cambridge release. “We explored a model in which this signal could be attributable to dark energy, rather than the dark matter the experiment was originally devised to detect.”

“We first need to know that this wasn’t simply a fluke,” Visinelli added. “If XENON1T actually saw something, you’d expect to see a similar excess again in future experiments, but this time with a much stronger signal.”

Despite constituting so much of the universe, dark energy has not yet been identified. Many models suggest that there may be some fifth force besides the known four known fundamental forces in the universe, one that is hidden until you get to some of the largest-scale phenomena, like the universe’s ever-faster expansion.

Axions shooting out of the Sun seemed a possible explanation for the excess signal, but there were holes in that idea, as it would require a re-think of what we know about stars. “Even our Sun would not agree with the best theoretical models and experiments as well as it does now,” one researcher told Gizmodo last year.

Part of the problem with looking for dark energy are “chameleon particles” (also known as solar axions or solar chameleons), so-called for their theorized ability to vary in mass based on the amount of matter around them. That would make the particles’ mass larger when passing through a dense object like Earth and would make their force on surrounding masses smaller, as New Atlas explained in 2019. The recent research team built a model that uses chameleon screening to probe how dark energy behaves on scales well beyond that of the dense local universe.

“Our chameleon screening shuts down the production of dark energy particles in very dense objects, avoiding the problems faced by solar axions,” said lead author Sunny Vagnozzi, a cosmologist at Cambridge’s Kavli Institute for Cosmology, in a university release. “It also allows us to decouple what happens in the local very dense Universe from what happens on the largest scales, where the density is extremely low.”

The model allowed the team to understand how XENON1T would behave if the dark energy were produced in a magnetically strong region of the Sun. Their calculations indicated that dark energy could be detected with XENON1T.

Since the excess was first discovered, the XENON1T team “tried in any way to destroy it,” as one researcher told The New York Times. The signal’s obstinacy is as perplexing as it is thrilling.

“The authors propose an exciting and interesting possibility to expand the scope of the dark matter detection experiments towards the direct detection of dark energy,” Zara Bagdasarian, a physicist at UC Berkeley who was unaffiliated with the recent paper, told Gizmodo in an email. “The case study of XENON1T excess is definitely not conclusive, and we have to wait for more data from more experiments to test the validity of the solar chameleons idea.”

The next generation of XENON1T, called XENONnT, is slated to have its first experimental runs later this year. Upgrades to the experiment will hopefully seal out any noise and help physicists home in on what exactly is messing with the subterranean detector.

SEE

LA REVUE GAUCHE - Left Comment: Search results for ETHER (plawiuk.blogspot.com)