China on track to operate African Tazara railway as powers vie for control of mineral trade routes

South China Morning Post

Sun, November 12, 2023

China has chosen China Civil Engineering Construction Corporation (CCECC) to negotiate a concession to operate the Tanzania-Zambia Railway line, as geopolitical tensions rise over control of trading routes for critical minerals in Africa.

CCECC, a subsidiary of the China Railway Construction Corporation, is expected to negotiate a public-private partnership concession in the form of a build-operate-transfer model with Tanzania and Zambia to operate Tazara.

It is also expected to upgrade the railway - which Chinese President Xi Jinping has called "a symbol of China-Africa friendship" - at an estimated cost of US$1 billion.

Do you have questions about the biggest topics and trends from around the world? Get the answers with SCMP Knowledge, our new platform of curated content with explainers, FAQs, analyses and infographics brought to you by our award-winning team.

The concession is expected to give a much-needed lifeline to the almost 50-year-old line, also known as Tazara, which was originally funded by Mao Zedong's government as a foreign aid project.

Last month, the Tanzania-Zambia Railway Authority announced the news, saying Chinese investors and CCECC were poised to play a significant role, hence the company's proposal was "expected imminently".

Observers have said the funding for the railway pointed to Beijing's keen interest in using Tazara for mining exports from Zambia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

But China is not alone - competition in the area with both the European Union and the United States is intensifying as the race for critical minerals used in the production of electric vehicle batteries heats up.

Tim Zajontz, a lecturer in global political economy at the University of Freiburg, said while the Chinese consortium would commit to invest in Tazara's ailing infrastructure and insufficient rolling stock, it was not an aid mission.

"The Chinese investors have made it unmistakably clear in previous negotiations that Tazara is no longer considered an aid project but that it must be a commercially viable venture," said Zajontz, who is also a research fellow in the Centre for International and Comparative Politics at Stellenbosch University.

Aly-Khan Satchu, a sub-Saharan Africa geoeconomic analyst, said the Tanzanian and Zambian governments seemed to be looking for a major revamp of the railway and were happy to concede the running of this line to the private sector.

"So I expect this to be a revamp, to operate as the concessionaire for a meaningful period of time," Satchu said.

He also noted Xi's keen interest in upgrading Tazara.

"This railway is a symbol of the Sino-African story and President Xi understands the power of the narrative," Satchu said.

Xi had promised to overhaul the railway when Tanzanian counterpart Samia Suluhu Hassan visited China last year and during Zambian President Hakainde Hichilema's visit in September.

"China is willing to support the upgrading and transformation of the Tanzania-Zambia Railway in accordance with the principles of marketisation and commercialisation," Xi said when he met Hichilema.

Zajontz said Tazara was part of the DNA of Sino-African relations, and often used to emphasise that China's dealings with Africa were based on equality, solidarity and anti-imperialism.

"Notwithstanding the official rhetoric, Beijing has also keen geoeconomic interests in Tazara's rehabilitation which would improve the performance of the Dar es Salaam corridor, not least for mining exports from Zambia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo," said Zajontz, whose coming book, The Political Economy of China's Infrastructure Development in Africa, discusses Tazara's planned privatisation.

When China's involvement in the Tazara railway began in the 1970s, the country was facing its own financial difficulties.

Meanwhile, Zambia was desperate for a railway link to the Tanzanian coast for its main export, copper. Neighbouring white-controlled Rhodesia - now Zimbabwe - had cut Zambia's only route to the sea in response to its transfer of power to the black majority.

The US and Russia both refused to fund a new railway, so China stepped in, building Tazara for about a billion yuan, or billions of US dollars at today's rates.

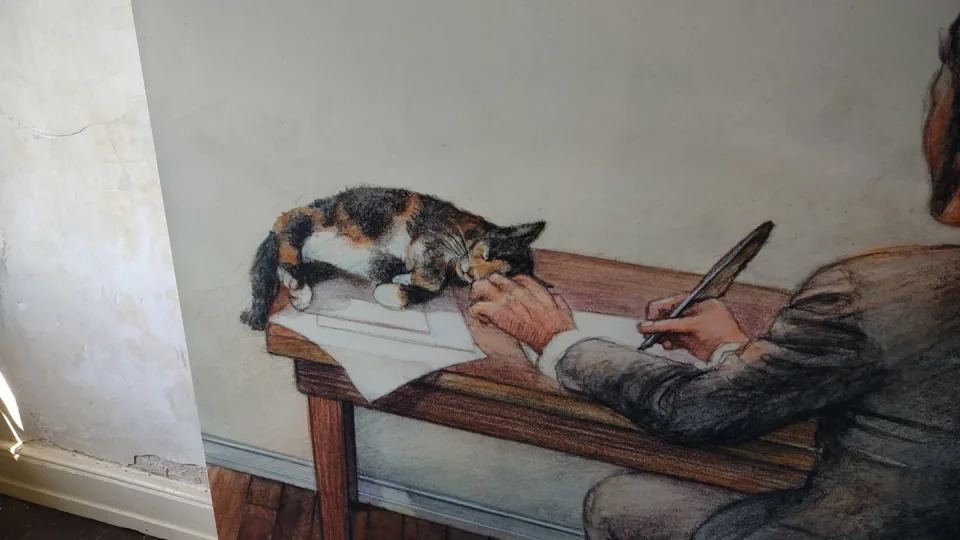

The Tazara Memorial Park in Zambia's Lusaka province commemorates Chinese nationals who died during the construction of the railway line in the 1970s. Photo: Xinhua alt=The Tazara Memorial Park in Zambia's Lusaka province commemorates Chinese nationals who died during the construction of the railway line in the 1970s. Photo: Xinhua>

From 1970 to 1975, as many as 50,000 Chinese workers were deployed to build the 1,860km (1,155 miles) of track stretching from Zambia's copper belt to the Tanzanian port of Dar es Salaam on the Indian Ocean.

It remains China's biggest overseas project to date, and managed to boost Beijing's political capital during the Cold War.

However, the American embassy in Zambia said in a post on X, formerly Twitter, that although China had funded Tazara's construction, it was the US that kept it running, with over US$45 million in help for "new locomotives and rolling stock" as well as "substantial technical assistance".

"Tazara has never reached its full potential," the embassy wrote on Thursday. "By the end of 1978, only two trains were operating daily."

"In the 1980s, the United States joined international partners in responding to Zambia and Tanzania's request to rehabilitate Tazara, with the US government providing over US$27 million through USAID," it added.

Zajontz said the embassy's post was a great example of how the "great powers" competed for public opinion across Africa.

"Everyone who knows a little bit about Tazara knows that eventually it will be privatised and that the Chinese would not allow a non-Chinese firm to run it - for obvious historical reasons," Zajontz said.

He added that the tweet showed how "desperate" both China and the West were in stressing how much they had invested in African infrastructure initiatives.

Tazara's upgrade follows EU and US announcements that they will fund the building of a railway from the Zambian copper belt to an existing line to the Angolan port of Lobito. They will also develop the Lobito transport corridor, which will connect inland southern DRC and northwest Zambia to regional and global trade markets via the Angolan port city.

The interest in the central African countries all circles back to minerals that are vital to the manufacture of electric batteries, including cobalt which is mined in the DRC and Zambia. Chinese companies have made vast investments in both countries.

"The US wants to chalk up something on the board and this Lobito corridor is a relatively bite-sized investment - but the US is a Johnny-come-lately and woefully behind the curve," Satchu said.

Zajontz said the West was keen to control its own transport routes in the region.

"Both the US and the EU want to prevent a situation in which Chinese transport or logistics firms could interrupt critical value chains if prompted as part of geopolitical escalations," Zajontz said.

"For Beijing, the recent announcement of Western investments along the Lobito corridor has certainly increased the geopolitical incentive to invest in and operate Tazara."

Emmanuel Matambo, research director at the University of Johannesburg's Centre for Africa-China Studies, said China understood the ideological and intangible value of Tazara, and so "the concession will not place high demands, if at all, on Zambia and Tanzania".

As a landlocked country, Zambia in particular had struggled to make efficient use of its neighbours' seaports and China was alive to that, he said. "The Tazara is more than a railway; it embodies China's long-standing solidarity with the developing world."

Matambo added that, unlike Tanzania where the ruling party had a firm hold on the incumbency, Zambia was more politically open and China had wanted to retain Zambia's friendship through leadership changes. Helping in tangible ways such as reviving Tazara would boost China's image in the eyes of Zambians, he said.

Copyright (c) 2023. South China Morning Post Publishers Ltd. All rights reserved.