Michael Natale

Mon, November 13, 2023

How Did Edgar Allan Poe Die?Bettmann - Getty Images

This story is a collaboration with Biography.com.

Edgar Allan Poe, the man who invented the detective story, saved his most unsolvable mystery for last: the cause of his own untimely death.

It’s been more than two centuries since Poe first entered this world, and despite dying only 40 years after doing so, he’s never truly left us. But Poe’s immortality is not through reincarnation, as it was for his “Morella” or “Ligeia.” Nor is it a resurrection, like in his famous “The Fall of the House of Usher” or his satirical “Some Words with a Mummy.”

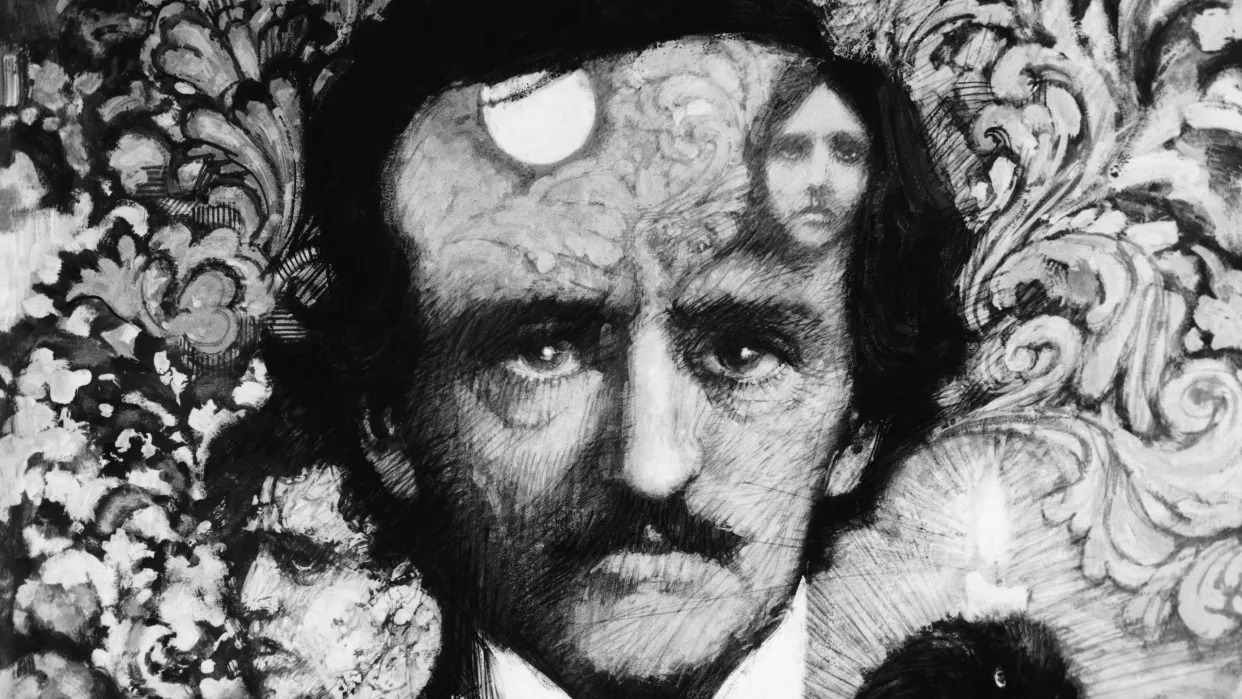

If any Edgar Allan Poe work anticipated how the author would find life after his mysterious death, it is the fate of the young bride in “The Oval Portrait”: a body withered away in neglect, the visage preserved forever in a work of art, even if the creation of that very art led to the subject's death.

Arthur Rackham’s illustration of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Oval Portrait,” wherein an artist is so absorbed in painting a portrait of his beautiful young bride that he fails to notice that she’s passed away while posing for him.

Culture Club - Getty Images

After all, Poe himself is still very present in the popular culture. In 2023, Mike Flanagan’s Poe-meets-Succession miniseries The Fall of the House of Usher rose to the top of the Netflix charts, and Austria’s official submission to the 2023 Eurovision Song Contest—“Who the Hell Is Edgar?”—is about singers Teya and Salena feeling like they’re possessed by the ghost of Poe.

But though Edgar Allan Poe is often viewed as the pre-imminent horror author of American letters, he’s also vibrantly present in the DNA of two other popular sub-genres of literature. For it’s through his invention of detective C. Auguste Dupin and his crime-solving technique of “ratiocination” in “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” that we get the groundwork for Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes and the entire thriving genre of detective fiction.

Likewise, it’s through the puzzling circumstances of Edgar Allan Poe’s mysterious death that we get an early taste of the “true crime” craze, as real-world amateur sleuths across two centuries have tried their hand at unravelling a mystery buried under layers of myth-making, medical quandaries, and possibly even political corruption.

After all, Poe himself is still very present in the popular culture. In 2023, Mike Flanagan’s Poe-meets-Succession miniseries The Fall of the House of Usher rose to the top of the Netflix charts, and Austria’s official submission to the 2023 Eurovision Song Contest—“Who the Hell Is Edgar?”—is about singers Teya and Salena feeling like they’re possessed by the ghost of Poe.

But though Edgar Allan Poe is often viewed as the pre-imminent horror author of American letters, he’s also vibrantly present in the DNA of two other popular sub-genres of literature. For it’s through his invention of detective C. Auguste Dupin and his crime-solving technique of “ratiocination” in “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” that we get the groundwork for Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes and the entire thriving genre of detective fiction.

Likewise, it’s through the puzzling circumstances of Edgar Allan Poe’s mysterious death that we get an early taste of the “true crime” craze, as real-world amateur sleuths across two centuries have tried their hand at unravelling a mystery buried under layers of myth-making, medical quandaries, and possibly even political corruption.

Edgar Allan Poe’s grave marker, erected in 1875 in Baltimore.

drnadig - Getty Images

The latest would-be Dupin to take a swing at the mystery of what, and perhaps who, killed Edgar Allan Poe is author Mark Dawidziak. In his 2023 book, A Mystery of Mysteries: The Death and Life of Edgar Allan Poe, Dawidziak posits a breakthrough new theory that incorporates a deadly illness that had previously claimed the life of both Poe’s mother and wife, and a fiendish and criminal act of the era called “cooping.”

But even Dawidziak acknowledges in his book that, though he has his theory, nobody knows anything for sure:

“Nobody can tell you with anything resembling certainty why, while traveling from Richmond to New York, he ended up in Baltimore. Nobody can tell you what happened to him during the missing days between his last sighting in Richmond on the evening of September 26 and his reappearance outside an Election Day polling place in Baltimore on the damp, chilly afternoon of October 3. Nobody has ever solved the identity of the person, Reynolds, for whom Poe supposedly called out for hours before he died at the Washington University Hospital of Baltimore. Nobody has ever produced conclusive evidence, or so much as a first cousin to it, regarding the cause of the delirium generally described as “congestion of the brain,” “cerebral inflammation,” or “brain fever.” Even the melodramatic and rather pat last words attributed to him—“Lord help my poor soul!”—have been called into question.”

But just how, exactly, could there be such a mystery around the death of Edgar Allan Poe, one of America’s most celebrated authors? Let’s take a look at the life and death of Edgar Allan Poe, as one simply can’t discuss one without the other. After all, as Poe himself put it in “The Premature Burial’: “The boundaries which divide Life from Death are at best shadowy and vague. Who shall say where the one ends, and where the other begins?”

The latest would-be Dupin to take a swing at the mystery of what, and perhaps who, killed Edgar Allan Poe is author Mark Dawidziak. In his 2023 book, A Mystery of Mysteries: The Death and Life of Edgar Allan Poe, Dawidziak posits a breakthrough new theory that incorporates a deadly illness that had previously claimed the life of both Poe’s mother and wife, and a fiendish and criminal act of the era called “cooping.”

But even Dawidziak acknowledges in his book that, though he has his theory, nobody knows anything for sure:

“Nobody can tell you with anything resembling certainty why, while traveling from Richmond to New York, he ended up in Baltimore. Nobody can tell you what happened to him during the missing days between his last sighting in Richmond on the evening of September 26 and his reappearance outside an Election Day polling place in Baltimore on the damp, chilly afternoon of October 3. Nobody has ever solved the identity of the person, Reynolds, for whom Poe supposedly called out for hours before he died at the Washington University Hospital of Baltimore. Nobody has ever produced conclusive evidence, or so much as a first cousin to it, regarding the cause of the delirium generally described as “congestion of the brain,” “cerebral inflammation,” or “brain fever.” Even the melodramatic and rather pat last words attributed to him—“Lord help my poor soul!”—have been called into question.”

But just how, exactly, could there be such a mystery around the death of Edgar Allan Poe, one of America’s most celebrated authors? Let’s take a look at the life and death of Edgar Allan Poe, as one simply can’t discuss one without the other. After all, as Poe himself put it in “The Premature Burial’: “The boundaries which divide Life from Death are at best shadowy and vague. Who shall say where the one ends, and where the other begins?”

Who Was Edgar Allan Poe?

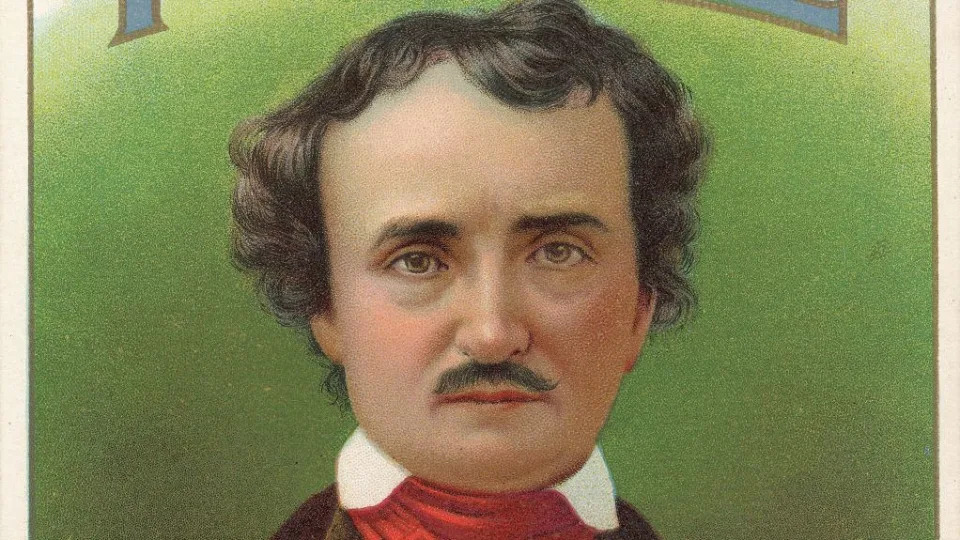

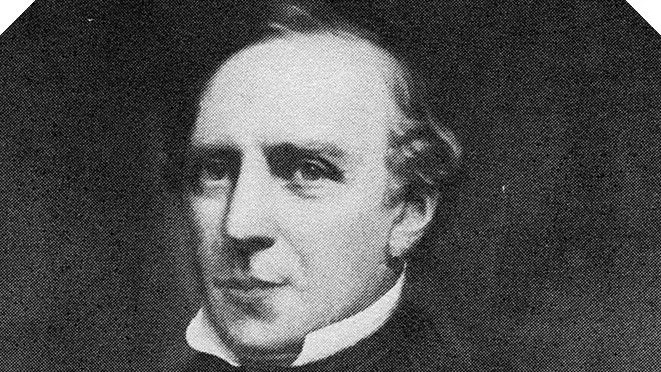

A 19th century etching of Edgar Allan Poe.

powerofforever - Getty Images

While virtually every major city along the U.S.’s East Coast now wishes to lay some sort of claim to the legacy of Edgar Allan Poe, only one can hold the title of his birthplace: Boston. Though, as The New England Grimpendium notes, neither the house in which he was born, nor even the street upon which the house could have been found, still exist in Boston today, wiped away by robust urban renewal efforts and perhaps a then-lack of public interest.

After all, while cities from Richmond, Virginia to New York City all now proudly boast a piece of Poe, it was not as though any of these cities, or anyone in them, had much interest in claiming the author in his early years. And that includes his own parents.

As Biography notes, “Edgar never really knew his biological parents: Elizabeth Arnold Poe, a British actor, and David Poe Jr., an actor who was born in Baltimore.” An alcoholic, reportedly frustrated with being seen as the lesser stage performer in his family when compared to his wife (as is suggested in Kenneth Silverman’s Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-ending Remembrance), David “left the family early in Edgar’s life.”

Which, it should be noted, is only the second worst thing an alcoholic stage actor frustrated at being viewed as the lesser performer in their family did in the 19th century.

While virtually every major city along the U.S.’s East Coast now wishes to lay some sort of claim to the legacy of Edgar Allan Poe, only one can hold the title of his birthplace: Boston. Though, as The New England Grimpendium notes, neither the house in which he was born, nor even the street upon which the house could have been found, still exist in Boston today, wiped away by robust urban renewal efforts and perhaps a then-lack of public interest.

After all, while cities from Richmond, Virginia to New York City all now proudly boast a piece of Poe, it was not as though any of these cities, or anyone in them, had much interest in claiming the author in his early years. And that includes his own parents.

As Biography notes, “Edgar never really knew his biological parents: Elizabeth Arnold Poe, a British actor, and David Poe Jr., an actor who was born in Baltimore.” An alcoholic, reportedly frustrated with being seen as the lesser stage performer in his family when compared to his wife (as is suggested in Kenneth Silverman’s Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-ending Remembrance), David “left the family early in Edgar’s life.”

Which, it should be noted, is only the second worst thing an alcoholic stage actor frustrated at being viewed as the lesser performer in their family did in the 19th century.

Hulton Archive - Getty Images

For her part, Elizabeth appears to have tried to tend to her children (Edgar had an older brother, William, and a younger sister, Rosalie), but died from tuberculosis when Edgar was only two years old.

“Separated from his brother, William, and sister, Rosalie,” Biography continues, “Poe went to live with his foster parents, John and Frances Allan, in Richmond, Virginia.” John Allan was in the tobacco business, and made no bones about wishing for Edgar to continue in his footsteps. Poe, however, had ambitions to become a poet, and at a young age began to write with feverish inspiration he attributed to his muse and fiancée, Sarah Elmira Royster.

But if John Allan was the first person of many in a position to help Poe achieve his ambitions, he was also the first person of many to decline to do so. His lack of support extended to the financial, and though Poe was reportedly an excellent student when he attended the University of Virginia, his academic life was cut short when John Allan refused to fund his studies. So, too, was his romance with Royster, who “had become engaged to someone else” in Poe’s absence.

And so, dejected and searching for a path forward, young Edgar Allan Poe returned to Boston.

The dilapidated cellar of Poe’s Philadelphia home, now maintained by the National Parks Service to appear as it did when the author resided there.

Michael Natale

Thus would begin a lifetime of odd jobs, low finances, and moving from place to place. Poe was briefly in the Army, briefly a cadet at West Point, and briefly employed by the Southern Literary Messenger. He resided in Boston, Richmond, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York City.

As a writer, Edgar Allan Poe penned poetry, literary criticisms (his reviews were so scathing they earned him the nickname “Tomahawk Man” and the ire of none other than Henry Wadsworth Longfellow), a novel (The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket), an essay on cosmology (Eureka: A Prose Poem), treatises critiquing the contemporary style of home decor (“The Philosophy of Furniture”), articles debunking hoaxes (“Maelzel’s Chess Player”), and even created some hoaxes of his own (“The Balloon-Hoax”).

In 1836, a 27-year-old Poe married Virginia Clemm, his 13-year-old cousin. While we naturally cannot know what occurred behind closed doors, it’s been suggested by several Poe scholars that theirs was a chaste marriage, one that was more a legal matter than one of carnal intentions. When Poe wrote of Virginia, he employed the term “maiden.” While this could have been simple literary flourish, it also could be used to indicate the virginal status of Virginia throughout their marriage. Virginia would, however, provide emotional support for the struggling author.

Indeed, acclaim largely eluded Poe until the publication of his poem “The Raven” in 1845, just four years before his death. Easily his most enduring and iconic composition, “The Raven” has permeated the American cultural lexicon as few poems have, and unlike so much of Poe’s work, it was recognized as exceptional by his peers at the time.

Thus would begin a lifetime of odd jobs, low finances, and moving from place to place. Poe was briefly in the Army, briefly a cadet at West Point, and briefly employed by the Southern Literary Messenger. He resided in Boston, Richmond, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York City.

As a writer, Edgar Allan Poe penned poetry, literary criticisms (his reviews were so scathing they earned him the nickname “Tomahawk Man” and the ire of none other than Henry Wadsworth Longfellow), a novel (The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket), an essay on cosmology (Eureka: A Prose Poem), treatises critiquing the contemporary style of home decor (“The Philosophy of Furniture”), articles debunking hoaxes (“Maelzel’s Chess Player”), and even created some hoaxes of his own (“The Balloon-Hoax”).

In 1836, a 27-year-old Poe married Virginia Clemm, his 13-year-old cousin. While we naturally cannot know what occurred behind closed doors, it’s been suggested by several Poe scholars that theirs was a chaste marriage, one that was more a legal matter than one of carnal intentions. When Poe wrote of Virginia, he employed the term “maiden.” While this could have been simple literary flourish, it also could be used to indicate the virginal status of Virginia throughout their marriage. Virginia would, however, provide emotional support for the struggling author.

Indeed, acclaim largely eluded Poe until the publication of his poem “The Raven” in 1845, just four years before his death. Easily his most enduring and iconic composition, “The Raven” has permeated the American cultural lexicon as few poems have, and unlike so much of Poe’s work, it was recognized as exceptional by his peers at the time.

An 1869 label for Raven brand tobacco, which depicts a scene from Poe’s story. Check out Biography for more on how Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven” has permeated pop culture across the years.

Transcendental Graphics - Getty Images

But the glow of literary recognition would only shine unencumbered for Edgar Allan Poe for two years after “The Raven” was published. As Biography notes, “In 1847, at the age of 24—the same age when Poe’s mother and brother also died—Virginia passed away from tuberculosis.” Poe was “overcome by grief following her death, and although he continued to work, he suffered from poor health and struggled financially until his death in 1849.”

But the glow of literary recognition would only shine unencumbered for Edgar Allan Poe for two years after “The Raven” was published. As Biography notes, “In 1847, at the age of 24—the same age when Poe’s mother and brother also died—Virginia passed away from tuberculosis.” Poe was “overcome by grief following her death, and although he continued to work, he suffered from poor health and struggled financially until his death in 1849.”

How Did Edgar Allan Poe Die?

MizC - Getty Images

Which brings us to those fateful few days in 1849.

As Biography frames it, “...things were looking up for Poe in October 1849.” But of course, that’s only what we can infer from the material aspects of his life at the time, as well as the posthumous stories relayed by people close to him, who weren’t always reliable. It is true that Poe was “...a star author who commanded great audiences for his readings, and he was about to marry his first love, Elmira Royster Shelton.”

However, one of the pitfalls of history, especially when it comes to the lives of artists, is the creation of a narrative. The earliest iteration of a “Poe narrative” came at the hands of a former rival-turned-executor of his literary estate, Rufus Wilmot Griswold, who opted to portray Poe, in the first official biography of the late author, as “a mentally deranged drunkard and womanizer.”

We’ve come to view Poe as the typical “tortured genius,” but more accurate assessments of Poe, coming from those close to him, would attempt to correct the record, particularly when it came to the writer’s drinking. (He was reportedly not much for alcohol, and was a lightweight on the occasions he did imbibe.)

But these recollections also fed into another irresistible narrative: that of the artist whose life was “just starting to come together” when it was tragically snuffed out. Remember that, especially around this time, the literary world was enthralled by stories of young poets dying well before their time.

The early 1820s had seen the untimely deaths of the Romantics John Keats and Percy Bysshe Shelley, both before the age of 30. By this time, the late Robert Burns (who died at 37 in 1796) was seeing a growing posthumous fanbase elevate him to such an echelon that, by 1880, he would have a statue erected in New York’s Central Park alongside Sir Walter Scott and William Shakespeare. And 11 years after that statue was erected, Arthur Rimbaud, author of the modernist prose poem A Season In Hell and agonized lover of fellow poet Paul Verlaine, would be snuffed out by cancer at age 37 and solidify the public’s idea of the tortured poet who died tragically young (for pop culture obsessives, think of this in much the same way we’ve sanctified the "27 Club"in rock music).

In the absence of facts, when it comes to the mysterious death of Edgar Allan Poe, it’s easy to be tempted to fill in the blanks with the narrative of your choice (tortured genius or tragic dreamer). But much like the witnesses probed in Poe’s “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” who mistake the shrieks of an orangutan for a foreign tongue because they’re manufacturing logic in the absence of fact, we also must avoid missing clues for the sake of forming a satisfying conclusion.

A lobby card for the 1932 Universal film Murders in the Rue Morgue starring Bela Lugosi. Though it shares its title with the Poe story, the film departs drastically from the original mystery tale to be near unrecognizable.LMPC - Getty Images

What Do We Actually Know About Edgar Allan Poe’s Death?

Hulton Archive - Getty Images

Here’s what we know happened for certain: On September 27, 1849, Edgar Allan Poe set out from Richmond to Philadelphia, with the intention of then heading to his cottage in The Bronx, New York. Next, on October 3, a printer named Joseph Walker recognized Poe, in what was described as a “delirious state,” outside of a tavern called Gunner’s Hall in Baltimore. It should be noted that the tavern, also known as Ryan’s Tavern, was at the time host to vote collectors for the 1849 election. It was common at the time for taverns to serve as polling places, and for men to be provided a drink upon casting their vote.

When Walker asked the distressed Poe if there was anyone he could contact for him, Poe named an editor he knew, Joseph Snodgrass. Walker wrote to Snodgrass:

"Dear Sir,

There is a gentleman, rather the worse for wear, at Ryan’s 4th ward polls, who goes under the cognomen of Edgar A. Poe, and who appears in great distress, & he says he is acquainted with you, and I assure you, he is in need of immediate assistance.

Yours, in haste,

JOS. W. WALKER

To Dr. J.E. Snodgrass."

Poe would be taken to Washington College Hospital, and what happened in his time there isn’t much clearer than what occurred before Walker discovered him outside the tavern—though in this case, the reason is a little more nefarious than poor record keeping. We know Poe was kept “alone in a windowless room with only one attendant physician, Dr. John Moran.” And we know that on October 7, without seemingly ever having explained the missing days, Poe died at the age of 40.

Edgar Allan Poe’s cause of death was recorded as “succumbing to phrenitis,” or congestion of the brain, which was also often employed to suggest a drug- or alcohol-related death. It isn’t clear how doctors made that determination. It has also been suggested that Poe uttered the final words, “Lord, help my poor soul,” but the reliability of this reporting has been called into question.

Poe was laid to rest in Baltimore. The author who had neither city nor family to permanently call home, spent his final days, and remains interred, in the very same city in which the father he never knew had been born.

What Are the Theories About Edgar Allan Poe’s Death?

The first theory proposed for what caused the mysterious death of Edgar Allan Poe came courtesy of Joseph Snodgrass, who blamed Poe’s demise on excessive alcohol consumption. It was a tidy explanation for Snodgrass; the doctor was an ardent advocate for temperance, and used every podium and paper he could find to blame Poe’s demise on alcohol consumption.

That Poe had opted to eschew alcohol altogether at the advice of his doctor, and had even joined the Sons of Temperance himself the year of his death, seemed to matter little to Snodgrass’s convenient conclusion.

Others have intimated everything from foul play and madness to rabies contracted from a pet cat. Poe did, indeed, love cats, and reportedly had expressed a reluctance to drink water in his final days, which Dr. R. Michael Benitez pointed to in 1996 to make the case for rabies as the author’s ultimate undoing. Had the man behind "The Gold-Bug" really gone the way of Old Yeller?

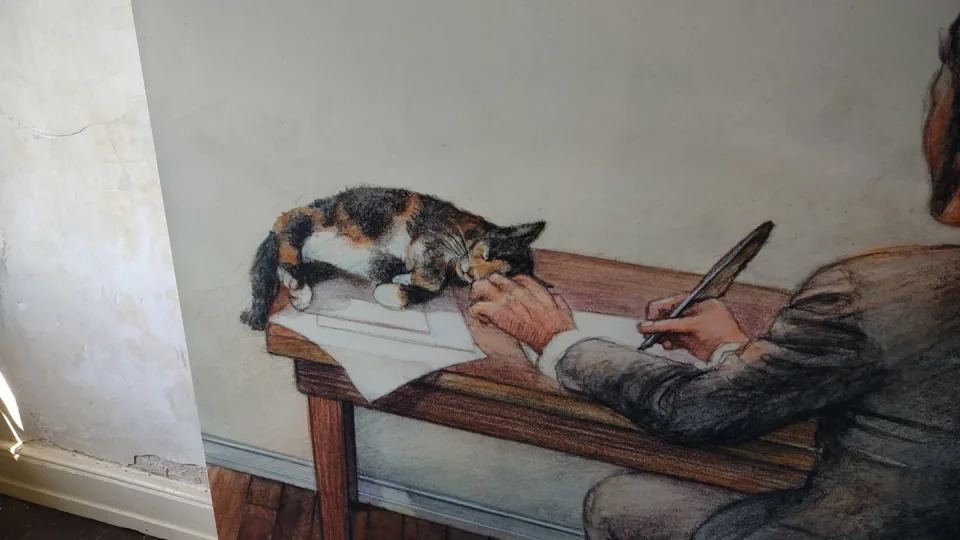

A piece of decor in the otherwise purposefully sparse home at Philadelphia’s Edgar Allan Poe National Historic Site depicts an ever-present cat on the author’s writing desk.

Michael Natale

Mark Dawidziak suggests what is, at first blush, the simplest solution: tuberculosis. As Biography notes, there was “an explosion in tuberculosis cases in the United States at the time,” to say nothing of the fact that the disease had claimed Poe’s wife, Virginia, just two years prior, so Poe had surely been exposed to it. And his symptoms, “like fever and delusions,” fit the diagnosis.

But Dawidziak also points to a more sinister element to explain Poe’s disappearance: the practice of cooping.

In the run-up to the so-called Gilded Age, the U.S. was rife with political machines that would bribe, bargain, and sometimes outright bully their way into positions of power. A common practice of the time was the act of rounding up vagrants and other powerless and unassuming men, trapping them in a confined space (hence “cooping”) and sending them out to various polling places under false names in order to cast fraudulent votes. The theory goes that Edgar Allan Poe was swept up in a cooping, subjected to the various mental and at times physical abuses that came with that, which caused both his absence and his subsequent strange behavior upon his discovery by Walker.

After all, Poe was discovered outside a polling place. And even if the notably “lightweight” man had eschewed alcohol personally, being forced to accept a drink at every tavern where he cast a fraudulent vote could explain a state of intoxication.

Some might balk at the suggestion that a “celebrity” could go unrecognized during all of this, but it’s important to remember that Edgar Allan Poe was merely a literary celebrity, with his image at best appearing as an etching in some newspapers and literary publications. The men actually orchestrating the coopings were often only a few poor choices away from being cooped themselves, usually the poverty-stricken or immigrants willing to do what they had to to survive.

Since we will never know for sure, and no C. Auguste Dupin has yet arrived to offer a conclusive explanation, we’re forced to choose which “story” we want to believe. For those who choose to believe the cooping story, there’s an extra bit of bitter irony to it all.

Mark Dawidziak suggests what is, at first blush, the simplest solution: tuberculosis. As Biography notes, there was “an explosion in tuberculosis cases in the United States at the time,” to say nothing of the fact that the disease had claimed Poe’s wife, Virginia, just two years prior, so Poe had surely been exposed to it. And his symptoms, “like fever and delusions,” fit the diagnosis.

But Dawidziak also points to a more sinister element to explain Poe’s disappearance: the practice of cooping.

In the run-up to the so-called Gilded Age, the U.S. was rife with political machines that would bribe, bargain, and sometimes outright bully their way into positions of power. A common practice of the time was the act of rounding up vagrants and other powerless and unassuming men, trapping them in a confined space (hence “cooping”) and sending them out to various polling places under false names in order to cast fraudulent votes. The theory goes that Edgar Allan Poe was swept up in a cooping, subjected to the various mental and at times physical abuses that came with that, which caused both his absence and his subsequent strange behavior upon his discovery by Walker.

After all, Poe was discovered outside a polling place. And even if the notably “lightweight” man had eschewed alcohol personally, being forced to accept a drink at every tavern where he cast a fraudulent vote could explain a state of intoxication.

Some might balk at the suggestion that a “celebrity” could go unrecognized during all of this, but it’s important to remember that Edgar Allan Poe was merely a literary celebrity, with his image at best appearing as an etching in some newspapers and literary publications. The men actually orchestrating the coopings were often only a few poor choices away from being cooped themselves, usually the poverty-stricken or immigrants willing to do what they had to to survive.

Since we will never know for sure, and no C. Auguste Dupin has yet arrived to offer a conclusive explanation, we’re forced to choose which “story” we want to believe. For those who choose to believe the cooping story, there’s an extra bit of bitter irony to it all.

Maryland Senator David StewartWikimedia Commons

We don’t have records of the down-ballot races a cooped Poe may have been forced to vote in to try and sway things, but we do know the two men that Maryland elected to the Senate during that 1849 election. One was James Alfred Pearce, who was the incumbent, and held the seat from 1843 all the way through to 1862, so it’s safe to safe that there needn’t have been much effort to corruptly sway the vote to save him. But the other was David Stewart, a Democrat running for a Senate seat that had previously been occupied by the Whig party member Reverdy Johnson, who had vacated the seat to serve in the cabinet of President Zachary Taylor. (Who had his own death under questionable circumstances, though that’s a story for another time.)

Stewart would indeed win his Senate race, striking a blow to the Whig dominance of Baltimore... for a single year. Just one year later, in 1850, Stewart would lose his Senate seat to the Whig party’s Thomas Pratt, who would occupy it for seven years thereafter. So if the cooping plot that may have captured Poe had been to sway the vote for the Democrat Stewart, then one of America’s most celebrated literary minds was snuffed out for a single year of a single Senate seat.

Why Do We Still Care About Edgar Allan Poe Today?

Michael Natale

As one of the most prominent authors of the American cultural lexicon, it’s not surprising that many of the cities Edgar Allan Poe occupied now not only lay claim to the author, but have also preserved or erected buildings devoted to the man. And as for whether the mystery of Poe’s death still transfixes the public, you need only see the patient exhaustion on the faces of the tour guides within the walls of any of these museums as yet another group of curious tourists press them for the “answer.” How much these institutions embrace the mystery can vary.

In Baltimore, whose NFL team takes its name from Poe’s most famous poem, you can board a “Bus Tour of Edgar Allan Poe’s Life and Death in Baltimore,” which will take you past the hospital where he died, and his two grave sites.

Pay a visit to the Poe Museum in Richmond and you can take part in a tribute to the author, which can include delivering a eulogy and searching for “Death Clues” to solve the mystery.

And at the Edgar Allan Poe National Historic Site in Philadelphia, the National Parks Department opts to not harp on Poe’s death, but rather, the time Poe spent in the still-preserved and sparsely decorated home (save for a charming reading room in the visitor’s center), and the stories he wrote therein. Though you can press a Park Ranger for their take on Poe’s death if you’re so inclined.

Michael Natale

In New York City, Poe’s footprint is a fair bit smaller than elsewhere, his proverbial ghost given less ground to haunt. In Manhattan, West 84th Street is also named Edgar Allan Poe Street, and a plaque on the side of a building suggests on that spot is where Poe composed “The Raven” (though other sites have claimed the same). While up in The Bronx, in a small patch of green known as Poe Park, the modest cottage in which the author resided still stands, though you can only get inside through a privately arranged tour through the Bronx Historical Society. Until September 2023, the cottage reportedly held an exhibit on the tragic deaths of both Virginia and Edgar Allan Poe for those fortunate enough to get inside to see it.

Adjacent to the cottage within the park is the Poe Park Visitor’s Center, operated by the City of New York. This particular facility isn’t focused on the history, or the mystery, of the author. Rather, it exists as a venue to showcase the artwork of current members of the community. It exists to create a space to encourage local artists in a manner Poe himself never had in life.

Edgar Allan Poe’s cottage behind a gate in Poe Park in The BronxMichael Natale

No comments:

Post a Comment