Starting in the ’80s, the rise of finance set forces in motion that have reshaped the economy

Ken-Hou Lin

Jan 2 · 2020

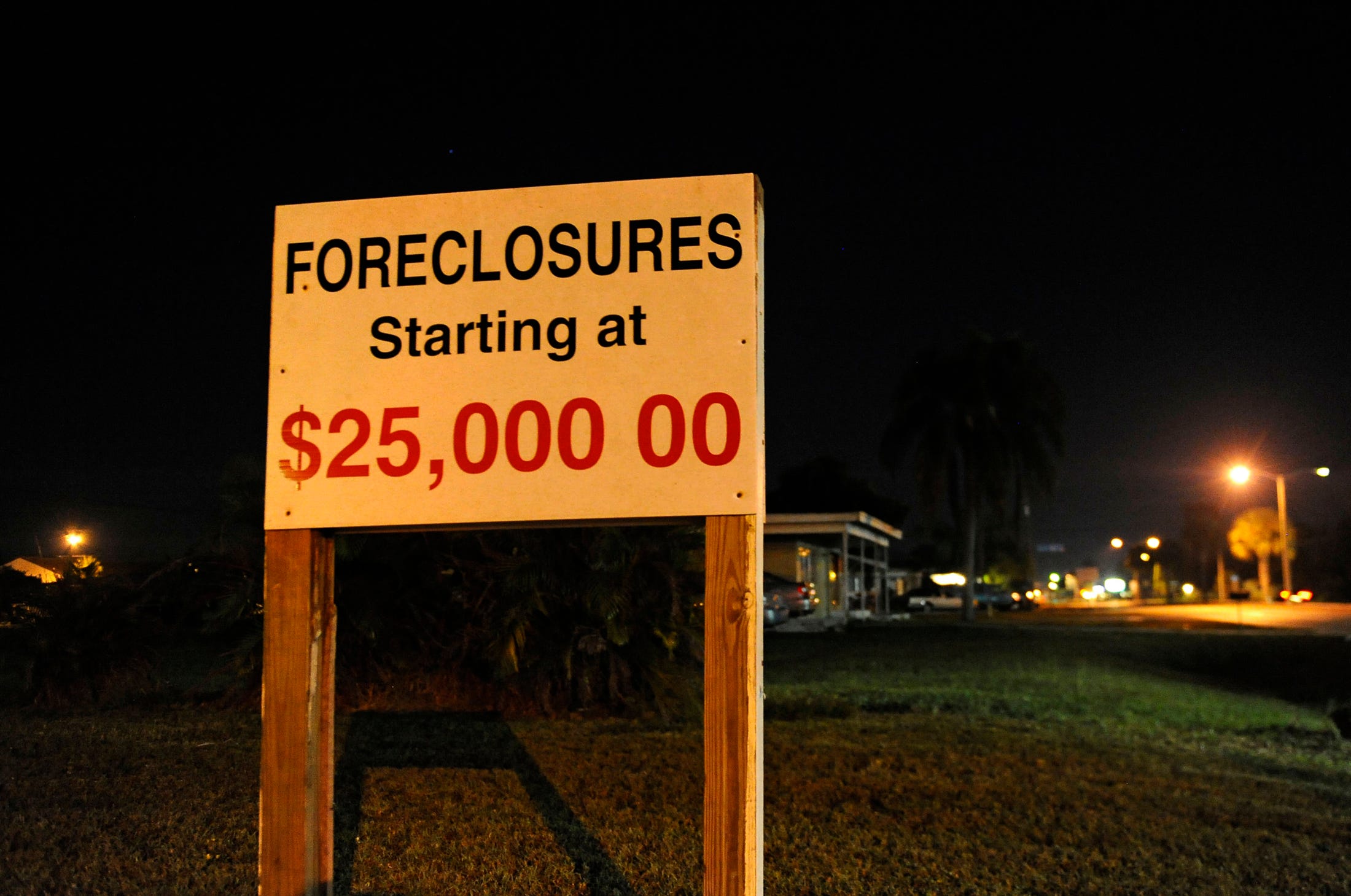

Photo: The Washington Post/Getty Images

Coauthored with Megan Tobias Neely, Postdoctoral Fellow in Sociology at The Clayman Institute for Gender Research at Stanford University.

These days, finance is so fundamental to our everyday lives that it is difficult to imagine a world without it. But until the 1970s, the financial sector accounted for a mere 15 percent of all corporate profits in the US economy. Back then, most of what the financial sector did was simple credit intermediation and risk management: banks took deposits from households and corporations and loaned those funds to homebuyers and business. They issued and collected checks to facilitate payment. For important or paying customers, they provided space in their vaults to safeguard valuable items. Insurance companies received premiums from their customers and paid out when a costly incident occurred.

These days, finance is so fundamental to our everyday lives that it is difficult to imagine a world without it. But until the 1970s, the financial sector accounted for a mere 15 percent of all corporate profits in the US economy. Back then, most of what the financial sector did was simple credit intermediation and risk management: banks took deposits from households and corporations and loaned those funds to homebuyers and business. They issued and collected checks to facilitate payment. For important or paying customers, they provided space in their vaults to safeguard valuable items. Insurance companies received premiums from their customers and paid out when a costly incident occurred.

By 2002, the financial sector had tripled, coming to account for 43% of all the corporate profits generated in the U.S. economy. These profits grew alongside increasingly complex intermediations such as securitization, derivatives trading, and fund management, most of which take place not between individuals or companies, but between financial institutions. What the financial sector does has become opaque to the public, even as its functions have become crucial to every level of the economy.

And as American finance expanded, inequality soared. Capital’s share of national income rose alongside compensation for corporate executives and those working on Wall Street. Meanwhile, among full-time workers, the Gini index (a measure of earnings inequality) increased 26%, and mass layoffs became a common business practice instead of a last resort. All these developments amplified wealth inequality, with the top 0.1% of U.S. households coming to own more than 20% of the entire nation’s wealth — a distribution that rivals the dominance of the robber barons of the Gilded Age. When the financial crisis of 2008 temporarily narrowed the wealth divide, monetary policies adopted to address it quickly resuscitated banks’ and affluent households’ assets but left employment tenuous and wages stagnant.

The past four decades of American history have therefore been marked by two interconnected, transformative developments: the financialization of the U.S. economy and the surge in inequality across U.S. society.

The rise of finance expanded the level of inequality since 1980 through three interrelated processes. First, it generated new intermediations that extract national resources from the productive sector and households to the financial sector without providing commensurate economic benefits. Second, it undermined the postwar accord between capital and labor by reorienting corporations toward financial markets and undermining the direct dependence on labor. And third, it created a new risk regime that transfers economic uncertainties from firms to individuals, which in turn increases the household demands for financial services.

As American corporations shift their focus from productive to financial activities, labor no longer represents a crucial component in the generation of profits, and the workers who perform productive tasks are devalued.

Economic rents

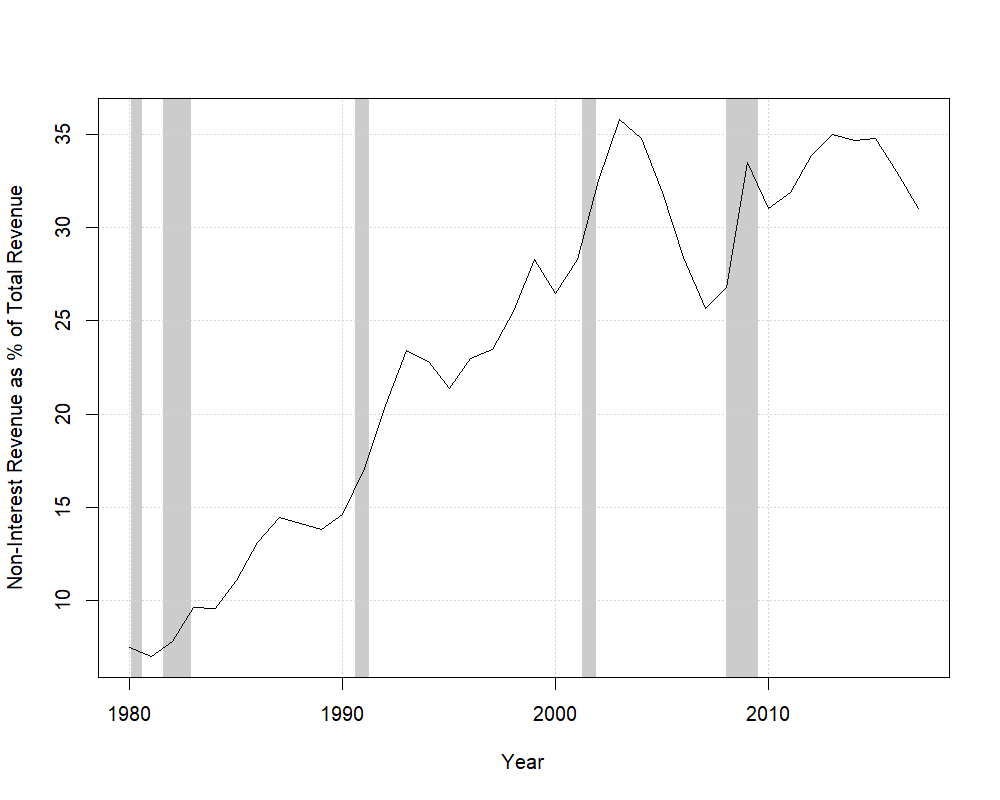

Where do all the financial sector’s profits come from? Most of the revenue for banks used to be generated by interest. By paying depositors lower interest rates than they charged borrowers, banks made profits in the “spread” between the rates. This business model began to change in the 1980s as banks expanded into trading and a host of fee-based services such as securitization, wealth management, mortgage and loan processing, service charges on deposit accounts (e.g., overdraft fees), card services, underwriting, mergers and acquisitions, financial advising, and market-making (e.g., IPOs [initial public offerings]). Altogether, these comprise the services that generate non-interest revenue.

Coauthored with Megan Tobias Neely, Postdoctoral Fellow in Sociology at The Clayman Institute for Gender Research at Stanford University.

These days, finance is so fundamental to our everyday lives that it is difficult to imagine a world without it. But until the 1970s, the financial sector accounted for a mere 15 percent of all corporate profits in the US economy. Back then, most of what the financial sector did was simple credit intermediation and risk management: banks took deposits from households and corporations and loaned those funds to homebuyers and business. They issued and collected checks to facilitate payment. For important or paying customers, they provided space in their vaults to safeguard valuable items. Insurance companies received premiums from their customers and paid out when a costly incident occurred.

These days, finance is so fundamental to our everyday lives that it is difficult to imagine a world without it. But until the 1970s, the financial sector accounted for a mere 15 percent of all corporate profits in the US economy. Back then, most of what the financial sector did was simple credit intermediation and risk management: banks took deposits from households and corporations and loaned those funds to homebuyers and business. They issued and collected checks to facilitate payment. For important or paying customers, they provided space in their vaults to safeguard valuable items. Insurance companies received premiums from their customers and paid out when a costly incident occurred.By 2002, the financial sector had tripled, coming to account for 43% of all the corporate profits generated in the U.S. economy. These profits grew alongside increasingly complex intermediations such as securitization, derivatives trading, and fund management, most of which take place not between individuals or companies, but between financial institutions. What the financial sector does has become opaque to the public, even as its functions have become crucial to every level of the economy.

And as American finance expanded, inequality soared. Capital’s share of national income rose alongside compensation for corporate executives and those working on Wall Street. Meanwhile, among full-time workers, the Gini index (a measure of earnings inequality) increased 26%, and mass layoffs became a common business practice instead of a last resort. All these developments amplified wealth inequality, with the top 0.1% of U.S. households coming to own more than 20% of the entire nation’s wealth — a distribution that rivals the dominance of the robber barons of the Gilded Age. When the financial crisis of 2008 temporarily narrowed the wealth divide, monetary policies adopted to address it quickly resuscitated banks’ and affluent households’ assets but left employment tenuous and wages stagnant.

The past four decades of American history have therefore been marked by two interconnected, transformative developments: the financialization of the U.S. economy and the surge in inequality across U.S. society.

The rise of finance expanded the level of inequality since 1980 through three interrelated processes. First, it generated new intermediations that extract national resources from the productive sector and households to the financial sector without providing commensurate economic benefits. Second, it undermined the postwar accord between capital and labor by reorienting corporations toward financial markets and undermining the direct dependence on labor. And third, it created a new risk regime that transfers economic uncertainties from firms to individuals, which in turn increases the household demands for financial services.

As American corporations shift their focus from productive to financial activities, labor no longer represents a crucial component in the generation of profits, and the workers who perform productive tasks are devalued.

Economic rents

Where do all the financial sector’s profits come from? Most of the revenue for banks used to be generated by interest. By paying depositors lower interest rates than they charged borrowers, banks made profits in the “spread” between the rates. This business model began to change in the 1980s as banks expanded into trading and a host of fee-based services such as securitization, wealth management, mortgage and loan processing, service charges on deposit accounts (e.g., overdraft fees), card services, underwriting, mergers and acquisitions, financial advising, and market-making (e.g., IPOs [initial public offerings]). Altogether, these comprise the services that generate non-interest revenue.

Figure 1. Note: The sample includes all FDIC-insured commercial banks. Source: Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Historical Statistics on Banking Table CB04

Figure 1 presents non-interest revenue as a percentage of commercial banks’ total revenue. Non-interest income constituted less than 10% of all revenue in the early 1980s, but its importance escalated and its share of income rose to more than 35% in the early 2000s. In other words, more than a third of all the bank revenue — particularly large banks’ revenue — is generated today by non-traditional banking activities. For example, JPMorgan Chase earned $52 billion in interest income but almost $94 billion in non-interest income right before the 2008 financial crisis. Half was generated from activities such as investment banking and venture capital, and a quarter from trading. In 2007, Bank of America earned about 47% of its total income from non-interest sources, including deposit fees and credit card services.

The ascendance of the new banking model led to a significant transfer of national resources into the financial sector in terms of not only corporate profits but also its elite employees’ compensation. Related industries, such as legal services and accounting, also benefit from the boom. However, whether these non-interest activities actually created values commensurate to their costs has been questioned, particularly when the sector has been dominated by only a handful of banks. In a way, these earnings could be considered economic rents — excessive returns without corresponding benefits.

The capital-labor accord

Besides extracting resources from the economy into the financial sector, financialization undermined the capital-labor accord by orienting non-financial firms toward financial markets. The capital-labor accord refers to an agreement and a set of production relations institutionalized in the late 1930s. The accord assigned managers full control over enterprise decision-making, and, in exchange, workers were promised real compensation growth linked to productivity, improved working conditions, and a high degree of job security. This agreement was reinforced by New Deal labor reforms such as unemployment insurance, the formal right to collective bargaining, maximum work hours, and minimum wages. As a result, for most of the 20th century, labor was considered a crucial driver for American prosperity. Its role, however, has been marginalized as corporations increasingly attend to the demands of the stock market.

To maximize the returns to their shareholders, American firms have adopted wide-ranging cost-cutting strategies, from automation to offshoring and outsourcing. Downsizing and benefit reductions are common ways that companies trim the cost of their domestic workforce. Many of these strategies are advocated by financial institutions, which earn handsome fees from mergers and acquisitions, spinoffs, and other corporate restructuring.

As non-financial firms expanded their operations to become lenders and traders, they came to earn a growing share of their profits from interest and dividends. The intensified foreign competition in the 1970s, combined with deregulated interest rates in the 1980s, drove this diversion, with large U.S. non-finance firms shifting investments from production to financial assets. Instead of targeting the consumers of their manufacturing or retail products to raise profits and reward workers, these firms extended their financial arms into leasing, lending, and mortgage markets to raise profits and reward shareholders.

Figure 1 presents non-interest revenue as a percentage of commercial banks’ total revenue. Non-interest income constituted less than 10% of all revenue in the early 1980s, but its importance escalated and its share of income rose to more than 35% in the early 2000s. In other words, more than a third of all the bank revenue — particularly large banks’ revenue — is generated today by non-traditional banking activities. For example, JPMorgan Chase earned $52 billion in interest income but almost $94 billion in non-interest income right before the 2008 financial crisis. Half was generated from activities such as investment banking and venture capital, and a quarter from trading. In 2007, Bank of America earned about 47% of its total income from non-interest sources, including deposit fees and credit card services.

The ascendance of the new banking model led to a significant transfer of national resources into the financial sector in terms of not only corporate profits but also its elite employees’ compensation. Related industries, such as legal services and accounting, also benefit from the boom. However, whether these non-interest activities actually created values commensurate to their costs has been questioned, particularly when the sector has been dominated by only a handful of banks. In a way, these earnings could be considered economic rents — excessive returns without corresponding benefits.

The capital-labor accord

Besides extracting resources from the economy into the financial sector, financialization undermined the capital-labor accord by orienting non-financial firms toward financial markets. The capital-labor accord refers to an agreement and a set of production relations institutionalized in the late 1930s. The accord assigned managers full control over enterprise decision-making, and, in exchange, workers were promised real compensation growth linked to productivity, improved working conditions, and a high degree of job security. This agreement was reinforced by New Deal labor reforms such as unemployment insurance, the formal right to collective bargaining, maximum work hours, and minimum wages. As a result, for most of the 20th century, labor was considered a crucial driver for American prosperity. Its role, however, has been marginalized as corporations increasingly attend to the demands of the stock market.

To maximize the returns to their shareholders, American firms have adopted wide-ranging cost-cutting strategies, from automation to offshoring and outsourcing. Downsizing and benefit reductions are common ways that companies trim the cost of their domestic workforce. Many of these strategies are advocated by financial institutions, which earn handsome fees from mergers and acquisitions, spinoffs, and other corporate restructuring.

As non-financial firms expanded their operations to become lenders and traders, they came to earn a growing share of their profits from interest and dividends. The intensified foreign competition in the 1970s, combined with deregulated interest rates in the 1980s, drove this diversion, with large U.S. non-finance firms shifting investments from production to financial assets. Instead of targeting the consumers of their manufacturing or retail products to raise profits and reward workers, these firms extended their financial arms into leasing, lending, and mortgage markets to raise profits and reward shareholders.

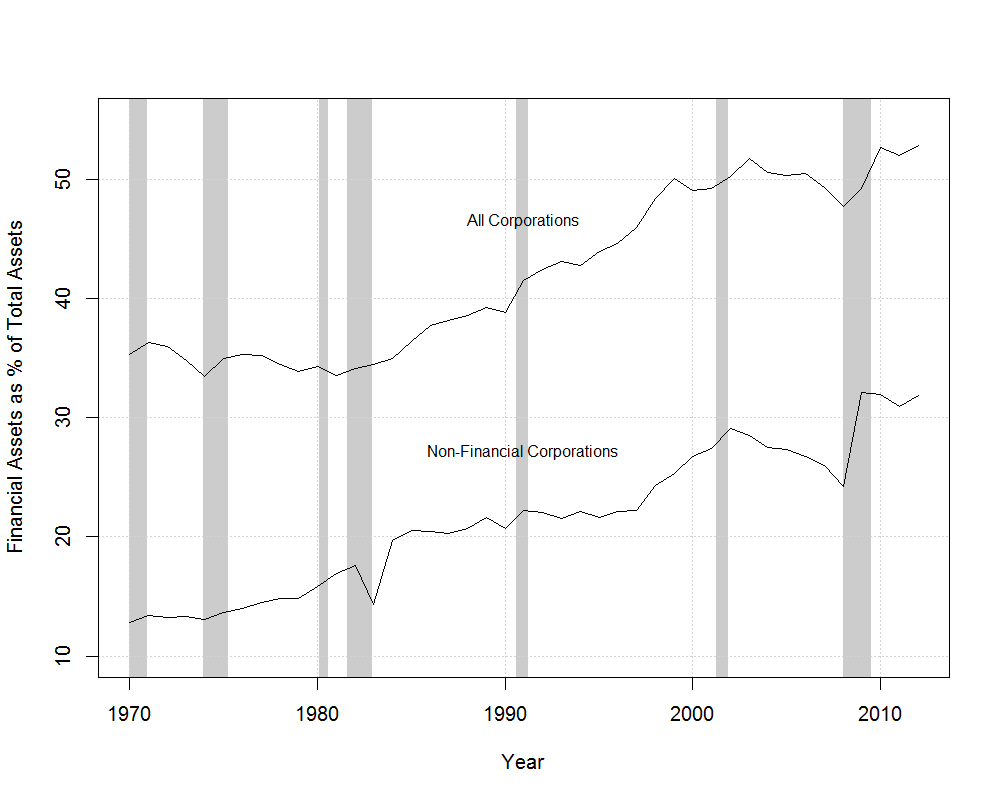

Figure 2. Note: Financial assets include investments in governmental obligations, tax-exempt securities, loans to shareholders, mortgage and real estate loans, and other investments, but do not include cash and cash equivalence. Financial corporations include credit intermediation, securities, commodities, and other financial investments, insurance carriers, other financial vehicles and investment companies, and holding companies. Source: Internal Revenue Service Corporation Complete Report Table 6: Returns of Active Corporations

Figure 2 shows the amount of financial assets owned by U.S. corporations as a percentage of their total assets. Financial assets here consist of treasury, state, and municipal bonds, mortgages, business loans, and other financial securities. In theory, financial holding is countercyclical, meaning that firms hold more financial assets during economic contractions and then invest these savings in productive assets during economic booms. However, there has been a secular upsurge in financial holding since the 1980s, from about 35% of their total assets to more than half. Even when we remove financial corporations from the picture, we see a rise in financial holding from under 15% to more than 30% in the aftermath of the recession. Again, as American corporations shift their focus from productive to financial activities, purchasing financial instruments instead of stores, plants, and machinery, labor no longer represents a crucial component in the generation of profits, and the workers who perform productive tasks are devalued.

In addition to marginalizing labor, the rise of finance pushed economic uncertainties traditionally pooled at the firm level downward to individuals. Prior to the 1980s, large American corporations often operated in multiple product markets, hedging the risk of an unforeseen downturn in any particular market. Lasting employment contracts afforded workers promotion opportunities, health, pension, and other benefits, unaffected by the risks the company absorbed. Since the 1980s, fund managers have instead pressured conglomerates to specialize only in their most profitable activities, pooling risk at the fund level, not at the firm level. Consequently, American firms have become far more vulnerable to sudden economic downturns. To cope with that increased risk, financial professionals advised corporations to reconfigure their employment relationships from permanent arrangements to ones that emphasize flexibility — the firm’s flexibility, not the employees’. Workers began to be viewed as independent agents rather than members or stakeholders of the firm. As more and more firms adopt contingent employment arrangements, workers are promised low minimum hours but are required to be available whenever they are summoned.

The compensation principle shifted, too, from a fair-wage model that sustains long-term employment relationships to a contingent model that ties wages and employment to profits (meaning more workers are involved in productivity pay schemes than they realize; should their portion of the company lag in profits, their job, not just their compensation, is on the line). Retirement benefits also transformed from guarantees of financial security to ones dependent on the performance of financial markets. Of course, this principle mostly benefits high-wage workers who can afford the fluctuations. Many low-wage workers, not knowing how many hours they will work and how much pay they will receive, are forced to borrow to meet their short-term needs.

Atomized risk regime

The dispersion of economic risks and the widening labor market divide are reflected in the growing consumption of financial products at the household level. As defined-contribution plans gradually replaced defined-benefit pensions as the default benefit in the private sector, mutual funds and retirement accounts flourished. This new retirement system allows workers to carry benefits over as they move across different employers (helpful when jobs are evermore precarious), but it ties their economic prospects to the fluctuation of financial markets. Families became responsible for making investment decisions and securing retirement funds for themselves.

Retirement in the United States, thus, is no longer an age but a financial status. Many middle-class families have had to cash out their retirement accounts to cover emergency expenses. Many others fear that they cannot afford to exit the workforce when the time comes. And these are the lucky ones.

The expansion of credit is supposed to narrow consumption inequality across households and smooth volatility. Instead, it adds to economic uncertainty.

About half of American workers have neither defined-benefit nor defined-contribution plans; that rate declines to a third among millennials. Affluent families, who allocate an increasing proportion of their wealth to financial assets, benefit, since they have sufficient resources to buffer downturns and can gain substantially from financialization. Still, the only sure winners are financial advisors and fund managers, who charge a percentage of these savings annually, without having to pay out when there are great losses.

The expansion of credit is supposed to narrow consumption inequality across households and smooth volatility across the life course. Instead, it, too, adds to economic uncertainty. The debate about whether Americans borrow too much obscures the reality that the consequences of debt vary dramatically across the economic spectrum (as well as by race and gender). The abundance of credit provides affluent families the opportunity to invest or meet short-term financial needs at low cost. At the same time, middle-income households carry increasingly heavy debt burdens, curtailing their ability to invest and save, and low-income households are either denied credit or face enormously high borrowing rates that go beyond preventing savings to imprison the impoverished in a cycle of debt payments.

More and more Americans are in the last category: unable to service their obligations (that is, to pay the bills on their debts), an increasing number of families have become insolvent, owning less than they owe. The credit market has been revealed as a regressive system of redistribution benefiting the rich and devastating the poor.

In this atomized risk regime, financial failure is attributed to individuals’ lack of morality or sophistication. Outside academic and leftist political circles, few question the overwhelming demand for toxic financial products such as payday loans, let alone the creation of those products. Instead, everyday workers are urged to educate themselves about the market, enhancing their financial literacy. “Financial inclusion” has become the buzzword of the day. Financial self-help like the perennial best-seller Rich Dad, Poor Dad and Secrets of the Millionaire Mind fly off the shelves, while entire governmental agencies and public outreach programs are established to promote the “savvy” use of financial products.

Taken together, the rising inequality in the United States is not a “natural” result of apolitical technological advancement and globalization. Economic inequality is not a necessary price we need to pay for economic growth. Instead, the widening economic divide reflects a deeper transformation of how the economy is organized and how resources are distributed.

Figure 2 shows the amount of financial assets owned by U.S. corporations as a percentage of their total assets. Financial assets here consist of treasury, state, and municipal bonds, mortgages, business loans, and other financial securities. In theory, financial holding is countercyclical, meaning that firms hold more financial assets during economic contractions and then invest these savings in productive assets during economic booms. However, there has been a secular upsurge in financial holding since the 1980s, from about 35% of their total assets to more than half. Even when we remove financial corporations from the picture, we see a rise in financial holding from under 15% to more than 30% in the aftermath of the recession. Again, as American corporations shift their focus from productive to financial activities, purchasing financial instruments instead of stores, plants, and machinery, labor no longer represents a crucial component in the generation of profits, and the workers who perform productive tasks are devalued.

In addition to marginalizing labor, the rise of finance pushed economic uncertainties traditionally pooled at the firm level downward to individuals. Prior to the 1980s, large American corporations often operated in multiple product markets, hedging the risk of an unforeseen downturn in any particular market. Lasting employment contracts afforded workers promotion opportunities, health, pension, and other benefits, unaffected by the risks the company absorbed. Since the 1980s, fund managers have instead pressured conglomerates to specialize only in their most profitable activities, pooling risk at the fund level, not at the firm level. Consequently, American firms have become far more vulnerable to sudden economic downturns. To cope with that increased risk, financial professionals advised corporations to reconfigure their employment relationships from permanent arrangements to ones that emphasize flexibility — the firm’s flexibility, not the employees’. Workers began to be viewed as independent agents rather than members or stakeholders of the firm. As more and more firms adopt contingent employment arrangements, workers are promised low minimum hours but are required to be available whenever they are summoned.

The compensation principle shifted, too, from a fair-wage model that sustains long-term employment relationships to a contingent model that ties wages and employment to profits (meaning more workers are involved in productivity pay schemes than they realize; should their portion of the company lag in profits, their job, not just their compensation, is on the line). Retirement benefits also transformed from guarantees of financial security to ones dependent on the performance of financial markets. Of course, this principle mostly benefits high-wage workers who can afford the fluctuations. Many low-wage workers, not knowing how many hours they will work and how much pay they will receive, are forced to borrow to meet their short-term needs.

Atomized risk regime

The dispersion of economic risks and the widening labor market divide are reflected in the growing consumption of financial products at the household level. As defined-contribution plans gradually replaced defined-benefit pensions as the default benefit in the private sector, mutual funds and retirement accounts flourished. This new retirement system allows workers to carry benefits over as they move across different employers (helpful when jobs are evermore precarious), but it ties their economic prospects to the fluctuation of financial markets. Families became responsible for making investment decisions and securing retirement funds for themselves.

Retirement in the United States, thus, is no longer an age but a financial status. Many middle-class families have had to cash out their retirement accounts to cover emergency expenses. Many others fear that they cannot afford to exit the workforce when the time comes. And these are the lucky ones.

The expansion of credit is supposed to narrow consumption inequality across households and smooth volatility. Instead, it adds to economic uncertainty.

About half of American workers have neither defined-benefit nor defined-contribution plans; that rate declines to a third among millennials. Affluent families, who allocate an increasing proportion of their wealth to financial assets, benefit, since they have sufficient resources to buffer downturns and can gain substantially from financialization. Still, the only sure winners are financial advisors and fund managers, who charge a percentage of these savings annually, without having to pay out when there are great losses.

The expansion of credit is supposed to narrow consumption inequality across households and smooth volatility across the life course. Instead, it, too, adds to economic uncertainty. The debate about whether Americans borrow too much obscures the reality that the consequences of debt vary dramatically across the economic spectrum (as well as by race and gender). The abundance of credit provides affluent families the opportunity to invest or meet short-term financial needs at low cost. At the same time, middle-income households carry increasingly heavy debt burdens, curtailing their ability to invest and save, and low-income households are either denied credit or face enormously high borrowing rates that go beyond preventing savings to imprison the impoverished in a cycle of debt payments.

More and more Americans are in the last category: unable to service their obligations (that is, to pay the bills on their debts), an increasing number of families have become insolvent, owning less than they owe. The credit market has been revealed as a regressive system of redistribution benefiting the rich and devastating the poor.

In this atomized risk regime, financial failure is attributed to individuals’ lack of morality or sophistication. Outside academic and leftist political circles, few question the overwhelming demand for toxic financial products such as payday loans, let alone the creation of those products. Instead, everyday workers are urged to educate themselves about the market, enhancing their financial literacy. “Financial inclusion” has become the buzzword of the day. Financial self-help like the perennial best-seller Rich Dad, Poor Dad and Secrets of the Millionaire Mind fly off the shelves, while entire governmental agencies and public outreach programs are established to promote the “savvy” use of financial products.

Taken together, the rising inequality in the United States is not a “natural” result of apolitical technological advancement and globalization. Economic inequality is not a necessary price we need to pay for economic growth. Instead, the widening economic divide reflects a deeper transformation of how the economy is organized and how resources are distributed.

From Divested by Ken-Hou Lin and Megan Tobias Neely. Copyright © 2020 by the authors and reprinted by permission of Oxford University Press. Full set of citations for the facts and figures in this excerpt can be found in the full text.

No comments:

Post a Comment