Even though statistics show a consistent downward trend in violent crime since the early 1990s, conservative politicians and media are trying to convince voters that America is under attack. Often these messages are geared toward rural voters to make them think large cities are rife with crime.

Colorado GOP chairman Dave Williams speaks before Republican presidential nominee former President Donald Trump at a campaign rally at the Gaylord Rockies Resort and Convention Center Friday, Oct. 11, 2024, in Aurora, Colo. (David Zalubowski, AP Photo)

The overarching message: the only way to keep this crime from infiltrating rural areas is to vote for conservatives.

Examples abound. On Monday, vice-presidential nominee J.D. Vance visited Minneapolis, stopping at the site of the Third Precinct, which burned in protests after the 2020 murder of George Floyd. Conservatives often criticize Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz, Kamala Harris’s running mate, for not doing more to stop the protests.

“The story of Minneapolis is coming to every community across the United States of America if we promote Kamala Harris to president of the United States,” Vance told a phalanx of media and supporters.

Nearly 6 in 10 Americans (58%) say that reducing crime should be a top priority for politicians. That number is nearly 7 out of 10 for Republican voters or those who lean Republican, according to the Pew Research Center. In comparison, three years ago the number of Americans who said reducing crime should be a priority was at 47%.

Experts on politics and political rhetoric say that voters in rural areas may be susceptible to claims of violent crime rampant in large cities because instead of seeing cities for themselves, they rely on news reports and political speeches.

“Conservative media has painted a wholly false picture of urban centers as ‘Mad Max’ wastelands where you can’t step out the door without getting stabbed or there are people dying of fentanyl overdoses on every corner,” says Brian Hughes, a research assistant professor in the Department of Justice, Law & Criminology at American University.

Hughs calls it a “divide-and-conquer” approach. “People who watch these reports are more fearful, less likely to connect with neighbors, less likely to visit the cities and experience lives of people who live there.”

The facts of violent incidences are often cherry-picked by politicians and held up as examples emblematic of a wider problem.

“The right is totally comfortable perverting the truth and the circumstances of a crime to fit a particular narrative,” says Seyward Darby, editor-in-chief of Atavist magazine and the author of Sisters in Hate: American Women on the Front Lines of White Nationalism (2020, Little, Brown and Company).

While voters say violent crime is up and that politicians should make fighting it a priority, they are more likely to believe it is a problem elsewhere rather than where they live. According to the Pew Research Center, 55% of people say there is more crime in their local area, while 77% believe crime rates are up nationally.

It’s only logical to realize that crime exists in rural areas. But in small towns where everyone seems to know each other’s business, it can be easier to explain away criminal actions, says Kevin Parsneau, a professor of political science at Minnesota State University, Mankato.

“You look around your hometown and let’s say somebody had a drug problem. Well, the thinking goes, they never had their life together to begin with. So then it becomes a personal thing.” Or, he adds, “You either misunderstand what’s going on in the city, or you don’t see what’s going on right in front of you.”

Exaggerating, misleading or simply false claims about crime is not a new tactic from the right.

“Fear mongering is one of the classic propaganda techniques. What it does is it softens us up, softens up our critical faculty,” Hughes says. He says this type of propaganda does an end run around intelligence, logic and reason, making it especially effective. This can be particularly true when the suspension of critical thinking is used as a pretext to dehumanize certain groups like immigrants.

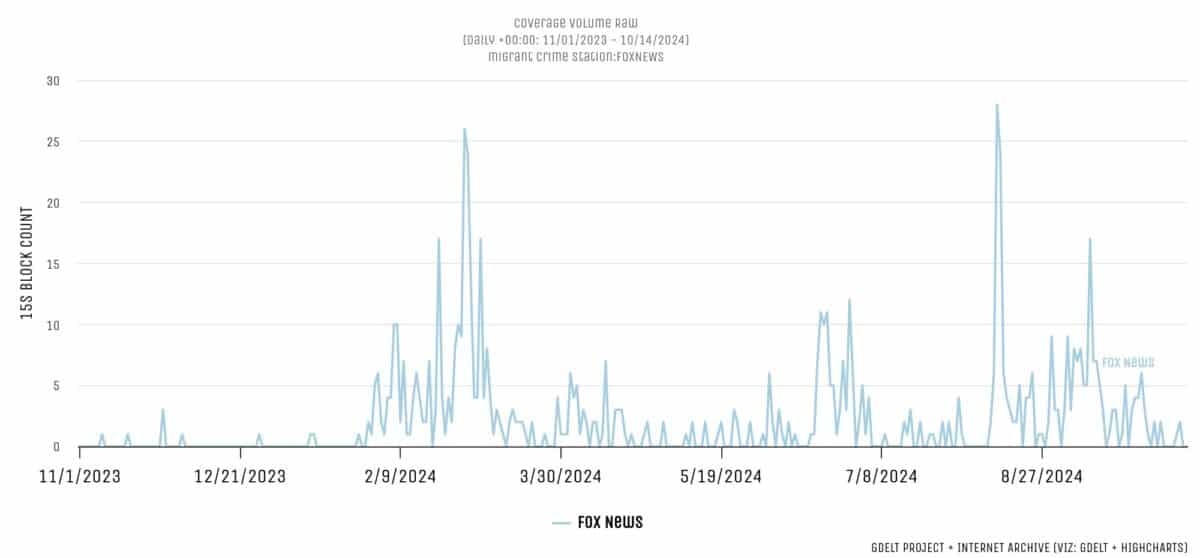

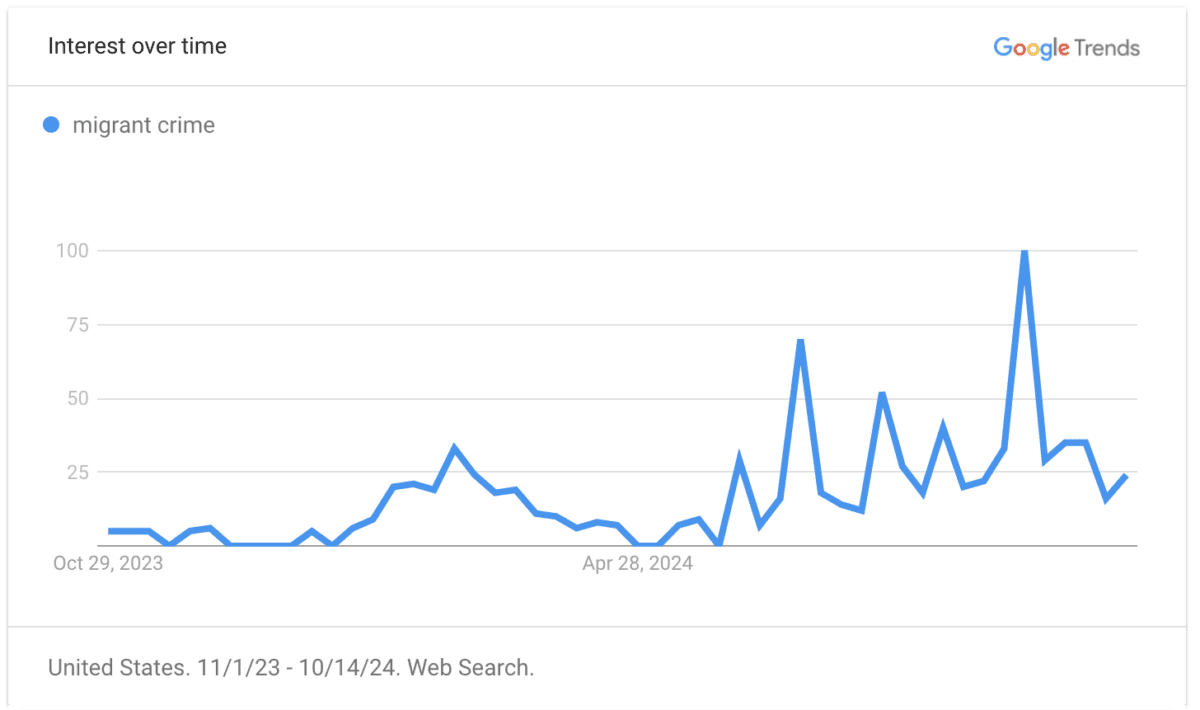

A constant refrain from both the Trump campaign and Fox News warns that “dangerous criminals” are flooding across the southern border at unprecedented rates, causing a wave of so-called “migrant crime.” The category may be invented but the rhetoric has real consequences, with Trump claiming that criminal illegal immigrants are “poisoning the blood” of this country. Aside from a few highly publicized cases, data show there is no increase in crime attributable to immigration. According to border officials, most migrants are families fleeing violence and poverty.

Darby says that this tactic can be found in the post-Civil War era. The Ku Klux Klan, founded in rural Tennessee, rose to prominence by promoting the idea that the end of slavery posed dangers to a white populace, particularly white women. Then, as now, the racial component of imagined crime was emphasized.

“I really don’t think a lot has changed,” she says. Over time, too, the American public has overestimated crime rates. Pew Research Center data shows for the past 30 years, in 23 out of 27 surveys about crime rates, at least 60% of adults said crime is on the rise, even when statistics show the opposite is true.

These attitudes on crime reflect media coverage, Parsneau says. Indeed, the saying “If it bleeds, it leads,” is a given on local television newscasts.

“Fear of crime correlates more with media coverage of crime than actual crime. So crime can be going up, but if the media aren’t talking about it, people aren’t that concerned. But if crime is going down, but the media is still talking about it, the fear of crime goes up,” Parsneau says. It’s the “mean world syndrome,” a phrase coined by communications scholar George Gerbner in the 1970s. When people learn about the wider world only through media reports, the media can shape a false reality.

People generally do not directly consult sources of crime statistics, such as the FBI or Bureau of Justice Statistics. Instead, they rely on local news reports or social media. Even for official statistics, there’s an atmosphere of distrust.

“Increasingly we see that people on the right do not care about official statistics and say, ‘No, that’s fake’ or ‘That’s someone lying,’ ” Darby says.

Even mainstream media don’t always remind voters of the hard facts, Parsneau says. Reporters, when asking politicians questions, might say something like, “A big issue for voters is crime. What are you going to do about violent crime?” without noting that violent crime rates are actually down.

In rural America, emphasis on crime takes attention away from other, more pressing issues, such as the agricultural economy and infrastructure needs.

Even though rural voters know those issues are important, “that doesn’t seem to overwhelm their fear that somebody from Mexico is going to sneak across the border and sell them fentanyl,” says Parsneau says. “It makes the assumption that we could reduce the amount of drugs if we could just stop them at the border. Well, they’re actually cooking the meth a few blocks away, so work on that.”

Hughes, who is also the associate director of Polarization and Extremism Research and Innovation Lab (PERIL) at American University, uses “attitudinal inoculation” to combat manipulative messages.

“It’s a tried-and-true practice demonstrated effectively hundreds of times in lab environments,” he says.

Attitudinal inoculation involves showing people a short sample of propaganda and warning them about manipulative methods they will see—for example, the use of deep, ominous sound effects to produce an unsettled feeling.

Hughes would like to see more money invested in helping people understand how political messaging can be manipulative. But it can be an uphill battle. Propaganda comes out of the big-money advertising industry. Show people how they are being manipulated politically, and they may also start to see how they are manipulated by advertising.

“It’s a tall order to get people with money to fight this,” Hughes says.

Even though political manipulation around crime is not new, it’s disheartening to see it continue to wield influence, Darby says.

“It reveals how little people learn, how prone we are as a society of making the same mistakes over and over.”

But Parsneau says to some degree, this could be politics as usual.

“If you’re the out party,” he says, “you want to portray everything that’s happening now as bad, as a justification as to why the Democrats should be thrown out.”

Rachael Hanel began her career as a newspaper reporter and now teaches creative nonfiction at Minnesota State University, Mankato. She’s the author of Not the Camilla We Knew: One Woman’s Path from Small-Town America to the Symbionese Liberation Army (2022) and We’ll Be the Last Ones to Let You Down: Memoir of a Gravedigger’s Daughter (2013).

No comments:

Post a Comment