Brain monitoring may be the future of work – how it could improve employee performance

The Conversation

January 7, 2025

Brain

Despite all the attention on technologies that reduce the hands-on role of humans at work – such as self-driving vehicles, robot workers, artificial intelligence and so on – researchers in the field of neuroergonomics are using technology to improve how humans perform in their roles at work.

Neuroergonomics is the study of human behavior while carrying out real-world activities, including in the workplace. It involves recording a person’s brain activity in different situations or while completing certain tasks to optimize cognitive performance. For example, neuroergonomics could monitor employees as they learn new material to determine when they have mastered it. It could also help monitor fatigue in employees in roles that require optimum vigilance and determine when they need to be relieved.

Until now, research in neuroergonomics could only be conducted in highly controlled clinical laboratory environments using invasive procedures. But engineering advances now make this work possible in real-world settings with noninvasive, wearable devices. The market for this neurotechnology – defined as any technology that interfaces with the nervous system – is predicted to grow to US$21 billion by 2026 and is poised to shape the daily life of workers for many industries in the years ahead.

But this advance doesn’t come without risk.

In my work as a biomedical engineer and occupational medicine physician, I study how to improve the health, well-being and productivity of workers. Neurotechnology often focuses on how workers could use wearable brain monitoring technologies to improve brain function and performance during tasks. But neuroergonomics could also be used to better understand the human experience at work and adapt tasks and procedures to the person, not the other way around.

Capturing brain activity

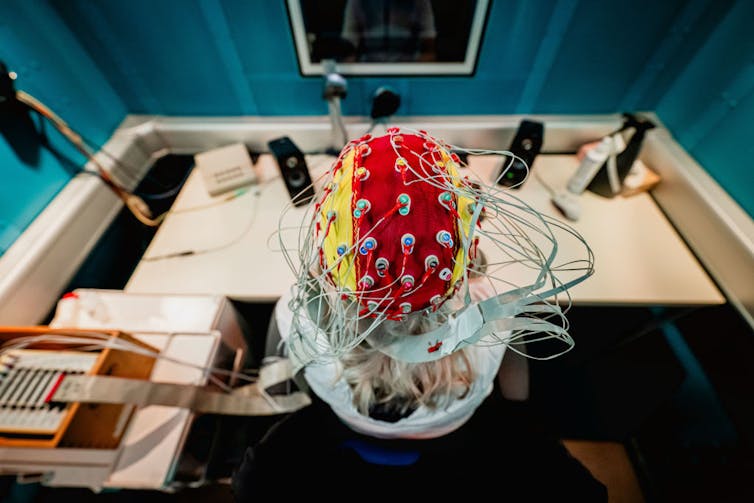

The two most commonly used neuroergonomic wearable devices capture brain activity in different ways. Electroencephalography, or EEG, measures changes in electrical activity using electrodes attached to the scalp. Functional near-infrared spectroscopy, or fNIRS, measures changes in metabolic activity. It does this by passing infrared light through the skull to monitor blood flow.

Both methods can monitor brain activity in real time as it responds to different situations, such as a high-pressure work assignment or difficult task. For example, a study using fNIRS to monitor the brain activity of people engaged in a 30-minute sustained attention task saw significant differences in reaction time between the beginning and the end of the task. This can be critical in security- and safety-related roles that require sustained attention, such as air traffic controllers and police officers.

Electroencephalography, or EEG, is one method of collecting brain activity. Jacob Schröter/picture alliance via Getty Images

Neuroergonomics also studies how brain stimulation could be used to improve brain activity. These include neuromodulation technologies like transcranial electrical stimulation, or tES; transcranial magnetic stimulation, or TMS; or focused ultrasound stimulation, or FUS. For example, studies have shown that applying tES while learning a cognitive training task can lead to immediate improvements in performance that persist even on the following day. Another study found that tES may also help improve performance on tasks that involve motor skills, with potential applications in surgical skills training, military tasks and athletic performance.

High-stakes ethical questions

The use of neurotechnology in the workplace has global implications and high stakes. Advocates say neurotechnology can encourage economic growth and the betterment of society. Those against neurotechnology caution that it could fuel inequity and undermine democracy, among other possible unknown consequences.

Ushering in a new era of individualized brain monitoring and enhancement poses many ethical questions. Answering those questions requires all stakeholders – workers, occupational health professionals, lawyers, government officials, scientists, ethicists and others – to address them.

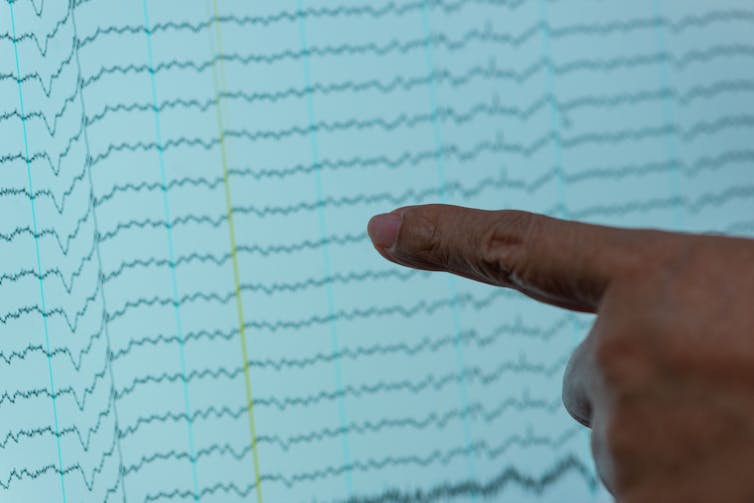

How to protect the brain activity data of workers remains unclear. Stock via Getty Images Plus

For example, how should an individual’s brain activity data be protected? There is reason to suspect that brain activity data wouldn’t be covered by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, or HIPAA, because it isn’t considered medical or health data. Additional privacy regulations may be needed.

Additionally, do employers have the right to require workers to comply with the use of neuroergonomic devices? The Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008 prevents discrimination against workers based on their genetic data. Similar legislation could help protect workers who refuse to allow the collection of their brain information from being fired or denied insurance.

Protecting workers

The data neurotechnology collects could be used in ways that help or hurt the worker, and the potential for abuse is significant.

Employers may be able to use neurotechnology to diagnose brain-related diseases that could lead to medical treatment but also discrimination. They may also monitor how individual workers respond to different situations, gathering insights on their behavior that could adversely affect their employment or insurance status.

Just as computers and the internet have transformed life, neurotechnologies in the workplace could bring even more profound changes in the coming decades. These technologies may enable more seamless integration between workers’ brains and their work environments, both enhancing productivity while also raising many neuroethical issues.

Bringing all stakeholders into the conversation can help ensure everyone is protected and create safer work environments aimed at solving tomorrow’s challenges.

Paul Brandt-Rauf, Professor and Dean of Biomedical Engineering, Drexel University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Op-Ed: The future of work — A shower cap full of electrodes on your head?

By Paul Wallis

DIGITAL JOURNAL

PublishedJanuary 7, 2025

Image by Andrea De Santis on unsplash

It’s called neuroergonomics, coming to an idiotic management team near you, eventually.

It’s about “studying brain performance at work and in everyday settings”. It’s sort of like surveillance, but much, much, dumber.

This tech is pretty basic. Its advocates use all the familiar sales pitches. There’s no indication of peer evaluation. It uses EEGs and metabolic monitoring, just a step up from last century. It also uses “transcranial magnetic stimulation”, which is used to provide “improvements during training”.

It’s also used for “mood control” and in treatments for depression, according to the Mayo Clinic.

If you think about the expression “at work”, a few things may have already come to mind, excuse the expression:

Most current jobs won’t exist anyway.

Strangely enough, cognitive training requires applied cognitive skills. How much cognition do you see in the world, let alone the workplace? Sounds more like a raffle.

Do you need neuro-anything when AI will do most of the work?

Neural science is in its somewhat brattish infancy at best.

This proto-level tech will be superseded pretty much immediately.

It’s likely to be extremely expensive. All that enthusiasm costs money, y’know.

You’ll be monitoring broke illiterates with the comprehension and literacy of an American.

There’s no information on whether management will be monitored.

The ethical issues are pretty well documented and very unimpressive. You can’t assume ethics will have any bearing on the actual use of the tech.

Imagine a performance review using this technology. It’s about the only thing that could be more farcical than the current performance reviews.

Highly stressed people in confined social spaces won’t do well with this tech. Lunatics, maybe. (It takes you six months to find out whether or not someone can do a job? Come off it, and you obviously can’t do your own job as a manager.)

Now’s my chance to endear myself to an entire sector –

Firstly – So what?

Who needs this tech?

The world seems to have survived without it.

Real-time monitoring of brainwaves seems like watching the dandruff pile up. Lacks depth. Imagine nitpicking about individual brainwaves.

It’s Management Science at its most mediocre.

(Have you guys ever managed anything at all, yourselves? Thought not.)

No thought seems to have gone into the environment in which this tech will be used. Add brain surveillance to the average hostile, insecure, partially insane workplace and what do you get? Nothing good, and nothing useful.

“A lawsuit with every headset” is far more likely than actual cost benefits.

The somewhat unsanitary stench of “B movie mind control cliches and plot lines” is hardly encouraging.

This tech could discriminate against individuals based on test outcomes. You can’t expect the science to help with that.

Remember this is the same science that will call anyone “neurodivergent” and pay itself lots to manage neurodivergence. The same science which has no comments to make on actual insanity and delusions at high levels.

How useful can this tech actually be to anyone?

There seem to be some performance metrics, mainly for people with medical conditions. Not in the workplace.

Why not?

Where are the usual “Aspiring halfwit Bozo Junior did a pirouette and back somersault on the differential equation and almost nobody got killed much”?

Imagine, O wary and wild-eyed reader:

You and your recently polished degree have had a stellar day at work. The strange owl-like neuro-person-thing even smiled at you as though you were worth smiling at. You take off your shower cap with electrodes and saunter effervescently back to your palatial cardboard box in Gangland.

Meh.

There’s too much to prove and nothing like enough proof.

__________________________________________________

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed in this Op-Ed are those of the author. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the Digital Journal or its members.

No comments:

Post a Comment