A new approach, not currently described by the Clean Air Act, could eliminate air pollution disparities

While air quality has improved dramatically over the past 50 years thanks in part to the Clean Air Act, people of color at every income level in the United States are still exposed to higher-than-average levels of air pollution.

A team led by researchers at the University of Washington wanted to know if the Clean Air Act is capable of reducing these disparities or if a new approach would be needed. The team compared two approaches that mirror main aspects of the Clean Air Act and a third approach that is not commonly used to see if it would be better at addressing disparities across the contiguous U.S. The researchers used national emissions data to model each strategy: targeting specific emissions sources across the U.S.; requiring regions to adhere to specific concentration standards; or reducing emissions in specific communities.

While the first two approaches—based on the Clean Air Act—didn't get rid of disparities, the community-specific approach eliminated pollution disparities and reduced pollution exposure overall.

The team published these findings Oct. 24 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

"In earlier research, we wanted to know which pollution sources were responsible for these disparities, but we found that nearly all sources lead to unequal exposures. So we thought, what's it going to take? Here, we tried three approaches to see which would be the best for addressing these disparities," said senior author Julian Marshall, a UW professor of civil and environmental engineering. "The two approaches that mirror aspects of the Clean Air Act were pretty weak at addressing disparities. The third approach, targeting emissions in specific locations, is not commonly done, but is something overburdened communities have been asking for for years."

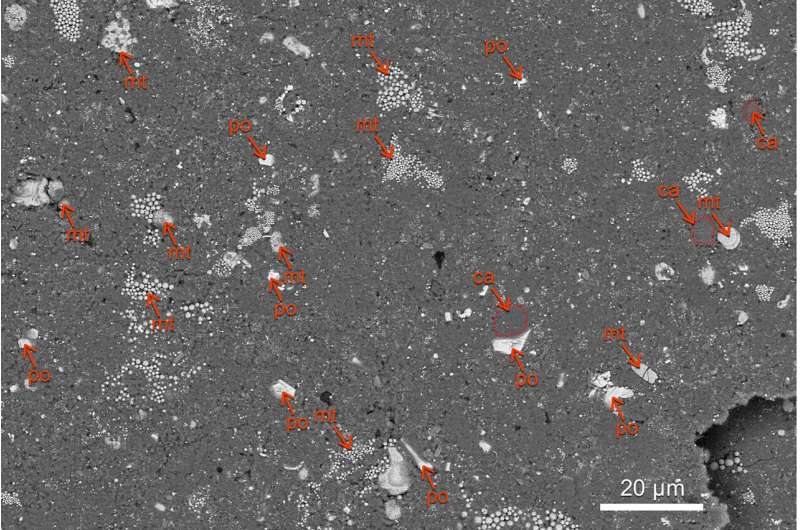

Fine particulate matter pollution, or PM2.5, is less than 2.5 micrometers in diameter—about 3% of the diameter of a human hair. PM2.5 comes from vehicle exhaust; fertilizer and other agricultural emissions; electricity generation from fossil fuels; forest fires; and burning of fuels such as wood, oil, diesel, gasoline and coal. These tiny particles can lead to heart attacks, strokes, lung cancer and other diseases, and are estimated to be responsible for about 90,000 deaths each year in the U.S.

The researchers tested the three potential strategies using a tool called InMAP, which Marshall and other co-authors developed. InMAP models the chemistry and physics of PM2.5, including how it is formed in the atmosphere, how it dissipates and how wind patterns move it from one location to another. The team modeled these approaches with national emissions data from 2014 because it was the most recent data set available at the time of this study.

The researchers looked at how efficiently and effectively each approach reduced average pollution exposure for all people and how well it eliminated the disparities for people of color.

While the emission source and concentration standards approaches were successful in reducing overall exposure across the country, these methods failed to address pollution disparities.

"Our optimization models what happens if we maximize the reductions in disparities. If an approach cannot address disparities even when optimized to do so, then any real-world implementation of the approach will also not address disparities," said lead author Yuzhou Wang, a doctoral student in civil and environmental engineering. "But we saw that even with less than 1% of emission reductions targeting specific locations, the pollution disparities that have persisted for decades were reduced to zero."

Implementing this location-specific approach would require additional work to identify which locations would be the best to target and working with the communities there to identify how to reduce emissions, the team said.

"Current regulations have improved average air pollution levels, but they have not addressed structural inequalities and often have ignored the voices and lived experiences of people in overburdened communities, including their requests to focus greater attention on sources impacting their communities," Marshall said. "These findings reflect historical experiences. Because of redlining and other racist urban planning from many decades ago, many pollution sources are more likely to be located in Black and brown communities. If we wish to address current inequalities, we need an approach that reflects and acknowledges this historical context."

Additional co-authors are Joshua Apte and Cesunica Ivey, both at the University of California, Berkeley; Jason Hill at the University of Minnesota; Regan Patterson at the University of California, Los Angeles; Allen Robinson at Carnegie Mellon University; and Christopher Tessum at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.People of color hardest hit by air pollution from nearly all sources