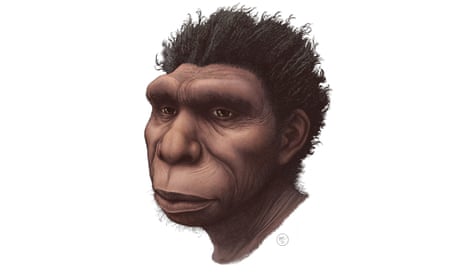

Fossils and ancient DNA paint a vibrant picture of human origins

A century of science has begun to explain how and where Homo sapiens and our kin evolved

A century ago, scientists knew almost nothing about our ancient ancestors, but have since discovered a wide range of relatives.

THE NATURAL HISTORY MUSEUM/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

By Erin Wayman

SEPTEMBER 15, 2021 AT 10:30 AM

In The Descent of Man, published in 1871, Charles Darwin hypothesized that our ancestors came from Africa. He pointed out that among all animals, the African apes — gorillas and chimpanzees — were the most similar to humans. But he had little fossil evidence. The few known human fossils had been found in Europe, and those that trickled in over the next 50 years came from Europe and from Asia.

Had Darwin picked the wrong continent?

Finally, in 1924, a fortuitous find supported Darwin’s speculation. Among the debris at a limestone quarry in South Africa, miners recovered the fossilized skull of a toddler. Based on the child’s blend of humanlike and apelike features, an anatomist determined that the fossil was what was then popularly known as a “missing link.” It was the most apelike fossil yet found of a hominid — that is, a member of the family Hominidae, which includes modern humans and all our close, extinct relatives.

That fossil wasn’t enough to confirm Africa as our homeland. Since that discovery, paleoanthropologists have amassed many thousands of fossils, and the evidence over and over again has pointed to Africa as our place of origin. Genetic studies reinforce that story. African apes are indeed our closest living relatives, with chimpanzees more closely related to us than to gorillas. In fact, many scientists now include great apes in the hominid family, using the narrower term “hominin” to refer to humans and our extinct cousins.

In a field with a reputation for bitter feuds and rivalries, the notion of humankind’s African origins unifies human evolution researchers. “I think everybody agrees and understands that Africa was very pivotal in the evolution of our species,” says Charles Musiba, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Colorado Denver.

Paleoanthropologists have sketched a rough timeline of how that evolution played out. Sometime between 9 million and 6 million years ago, the first hominins evolved. Walking upright on two legs distinguished our ancestors from other apes; our ancestors also had smaller canine teeth, perhaps a sign of less aggression and a change in social interactions. Between about 3.5 million and 3 million years ago, humankind’s forerunners ventured beyond wooded areas. Africa was growing drier, and grasslands spread across the continent. Hominins were also crafting stone tools by this time. The human genus, Homo, arrived between 2.5 million and 2 million years ago, maybe earlier, with larger brains than their predecessors. By at least 2 million years ago, Homo members started traveling from Africa to Eurasia. By about 300,000 years ago, Homo sapiens, our species, emerged.

All in the family

Fossil finds suggest that many hominin species have lived over the last 7 million years (dates for each species are based on those finds), though researchers debate the validity of some of these classifications. The earliest purported hominins (purple) show some signs of upright walking, which became more routine with the rise of Australopithecus (green). Seemingly short-lived Paranthropus (yellow) was adapted for heavy chewing, and brain size began to increase in Homo species (blue).

H. THOMPSON

But human evolution was not a gradual, linear process, as it appeared to be in the 1940s and ’50s. It did not consist of a nearly unbroken chain, one hominin evolving into the next through time. Fossil discoveries in the ’60s and ’70s revealed a bushier family tree, with many dead-end branches. By some counts, more than 20 hominin species have been identified in the fossil record. Experts disagree on how to classify all of these forms — “Fossil species are mental constructs,” a paleoanthropologist once told Science News — but clearly, hominins were diverse, with some species overlapping in both time and place.

Even our species wasn’t always alone. Just 50,000 years ago, the diminutive, 1-meter-tall Homo floresiensis, nicknamed the hobbit, lived on the Indonesian island of Flores. And 300,000 years ago, Homo naledi was a neighbor in South Africa.

Finding such “primitive” species — both had relatively small brains — living at the same time as H. sapiens was a big surprise, says Bernard Wood, a paleoanthropologist at George Washington University in Washington, D.C. Those discoveries, made within the last two decades, were reminders of how much is left to learn.

It’s premature to pen a comprehensive explanation of human evolution with so much ground — in Africa and elsewhere — to explore, Wood says. Our origin story is still a work in progress.

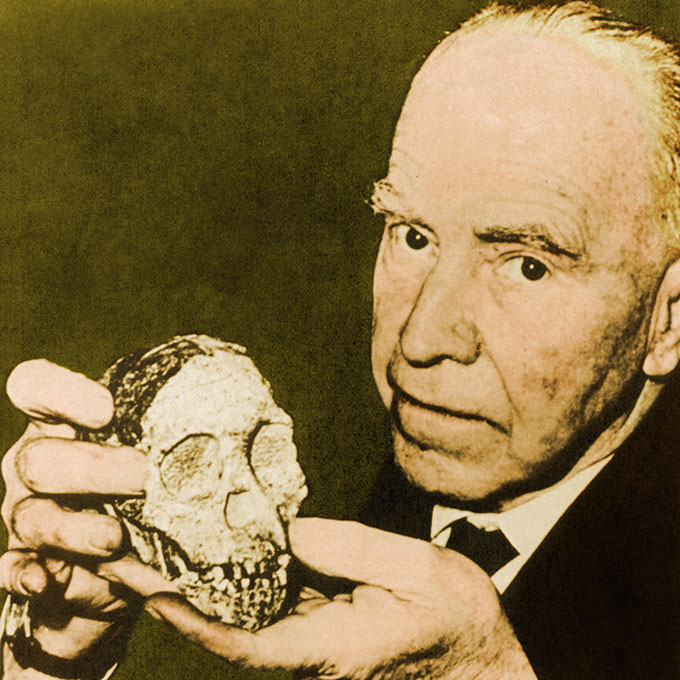

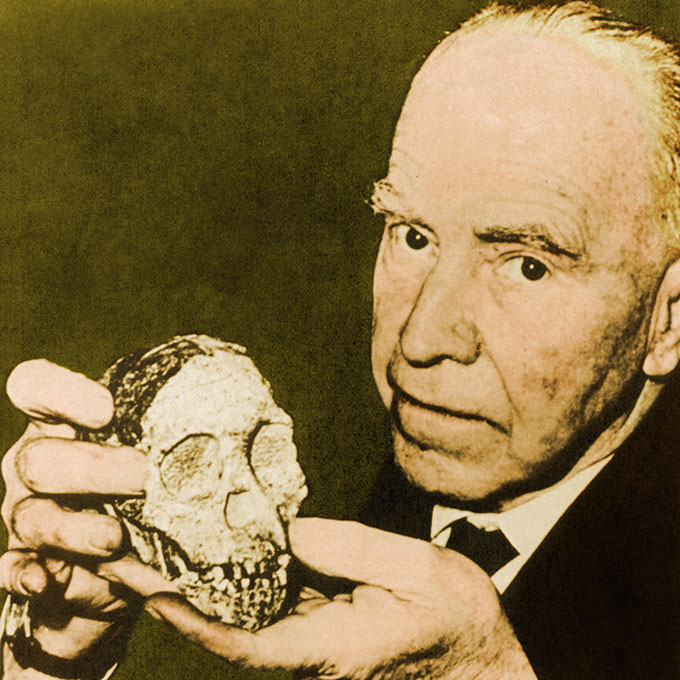

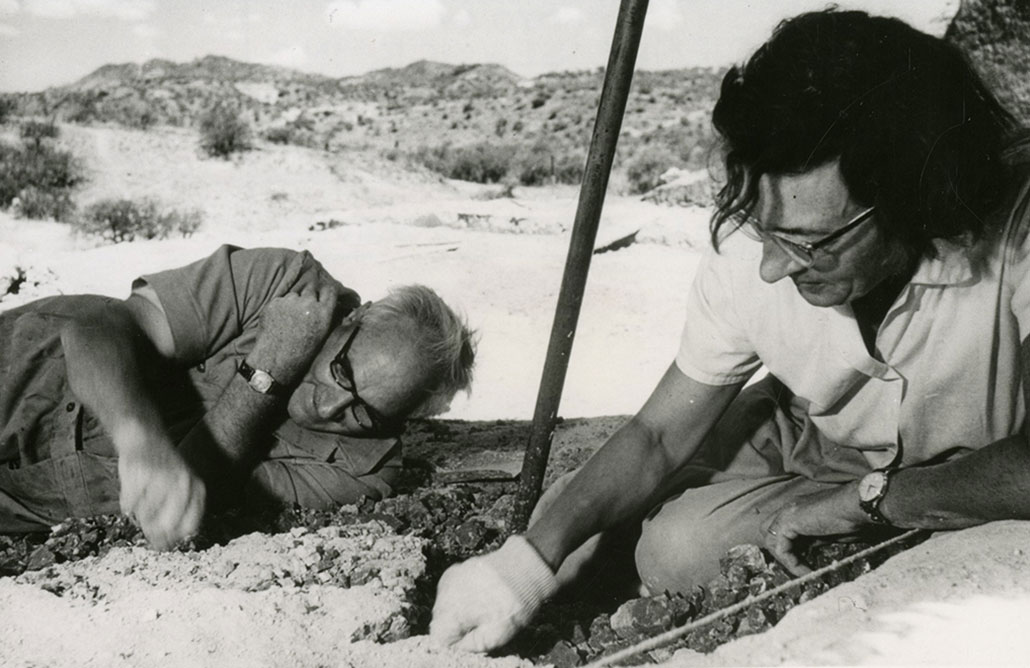

Raymond Dart had a wedding to host.

It was a November afternoon in 1924, and the Australian-born anatomist was partially dressed in formal wear when he was distracted by fossils. Rocks containing the finds had just been brought to his home in Johannesburg, South Africa, from a mine near the town of Taung.

Raymond Dart recognized that the Taung Child (shown with Dart decades after its 1924 discovery) had both apelike and humanlike qualities. The find sparked the search for more hominin fossils in Africa.

SCIENCE HISTORY IMAGES/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

Imprinted on a knobby rock about as big as an orange were the folds, furrows and even blood vessels of a brain. It fit perfectly inside another rock that had a bit of jaw peeking out.

The groom pressed Dart to get back on track. “My god, Ray,” he said. “You’ve got to finish dressing immediately — or I’ll have to find another best man.”

As soon as the festivities ended, Dart, 31 years old at the time, started removing the jaw from its limestone casing, chipping away with knitting needles. A few weeks later, he had liberated not just a jaw but a partial skull preserving the face of a child.

On February 7, 1925, in the journal Nature, Dart introduced the Taung Child to the world. He described the fossil as an ape like no other, one with some distinctly humanlike features, including a relatively flat face and fairly small canine teeth. The foramen magnum, the hole through which the spinal cord exits the head, was positioned directly under the skull, implying the child had an erect posture and walked on two legs.

Dart concluded that the Taung Child belonged to “an extinct race of apes intermediate between living anthropoids and man.” His italicized text emphasized his judgment: The fossil was a so-called missing link between other primates and humans. He named it Australopithecus africanus, or southern ape of Africa.

The Taung Child was the second hominin fossil discovered in Africa, and much more primitive than the first. Dart argued that the find vindicated Darwin’s belief that humans arose on that continent. “There seems to be little doubt,” Science News Letter, the predecessor of Science News, reported, “that there has been discovered on the reputed ‘dark’ continent a most important step in the evolutionary history of man.”

But Dart’s claims were mostly met with skepticism. It would take more than two decades of new fossil finds and advances in geologic dating for Dart to be vindicated — and for Africa to become the epicenter of paleoanthropology.

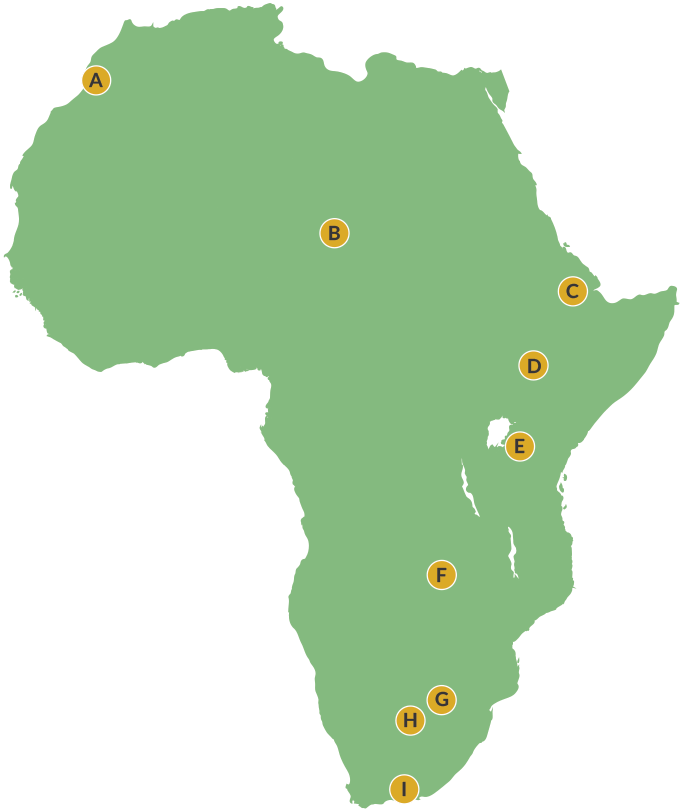

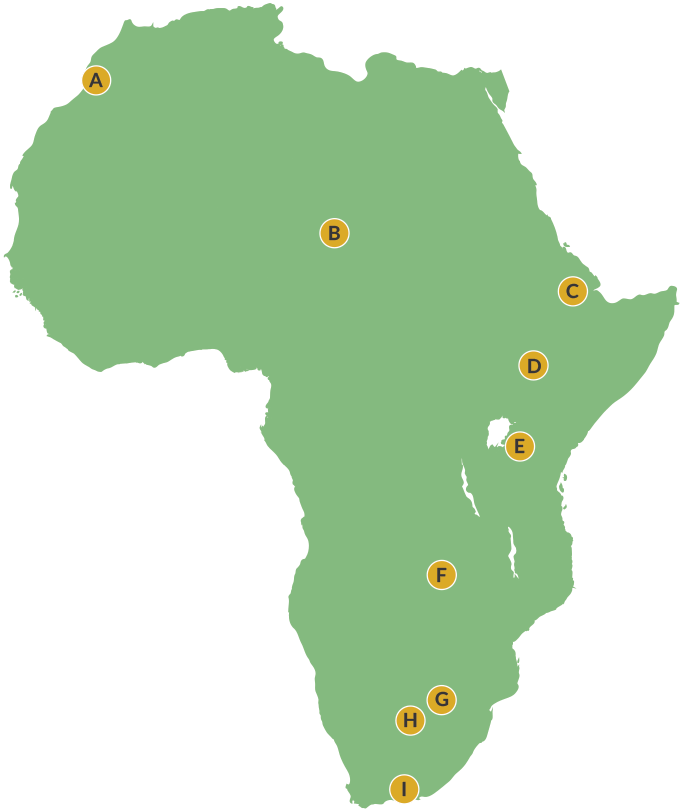

Hot spots

This map marks locations of some of human evolution’s biggest fossil discoveries. The search in Africa began in the 1920s. Yet there is still much of the continent left to explore, as paleoanthropologists have mostly focused on eastern and southern Africa.

A. The oldest known Homo sapiens fossils, dating to about 300,000 years ago, come from Jebel Irhoud in Morocco.

B. At the Toros-Menalla site in Chad, scientists found what may be the earliest known hominin, Sahelanthropus tchadensis.

C. Ethiopia’s Afar region hosts numerous sites, some stretching back more than 5 million years. Major finds include the early hominin Ardipithecus and Lucy.

D. Southern Ethiopia and northern Kenya hold a long hominin history, including Australopithecus fossils, some of the oldest known stone tools, early Homo fossils and early H. sapiens fossils.

E. Louis and Mary Leakey put Tanzania’s Olduvai Gorge on the map with discoveries of Paranthropus boisei and Homo habilis. The nearby Laetoli site preserves hominin footprints dating to 3.6 million years ago.

F. The Kabwe skull, the first hominin fossil found in Africa, came from a mine in Zambia in 1921.

G. South Africa’s limestone caves have yielded Australopithecus, Paranthropus and Homo fossils.

H. Quarry workers near Taung, South Africa, recovered the first Australopithecus fossil ever found.

I. At caves along coastal South Africa, scientists have recovered a rich record of H. sapiens activity, including what may be the earliest known drawing and other signs of symbolic behavior.

SOURCE: NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL/UNDERSTANDING CLIMATE’S INFLUENCE ON HUMAN EVOLUTION 2010; ADAPTED BY E. OTWELL

Against the establishment

Unlike Darwin, many evolutionists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries had theorized that the human family tree was rooted in Asia. Some argued that Asia’s gibbons were our closest living relatives. Others reasoned that tectonic activity and climate change in Central Asia sparked human evolution. One naturalist even proposed that human origins traced back to a lost continent that had sunk in the Indian Ocean, forcing our ancestors to relocate to Southeast Asia.

And that’s where the best contender for an early human ancestor had been found. In the 1890s, a crew led by Dutch physician-turned-anthropologist Eugène Dubois had uncovered a skullcap and thigh bone on the Indonesian island of Java. The thick skullcap had heavy brow ridges, but Dubois estimated it once held a brain that was about twice as big as an ape’s and approaching the size of a human’s. The thigh bone indicated that this Java Man, later named Homo erectus, walked upright.

Europe had its own tantalizing fossils. Neandertals had been known since the mid-19th century, but by the early 20th century, they were generally thought to be cousins that lived too recently to shed much light on our early evolution. A more relevant discovery seemed to come in 1912, when an amateur archaeologist had recovered humanlike bones from near Piltdown, England; the site also contained fossils of extinct creatures, suggesting Piltdown Man was of great antiquity. Skull bones hinted he had a human-sized brain, but his primitive jaw had a large, apelike canine tooth.

Some experts questioned whether the skull and jaw belonged together. But British scientists embraced the discovery — and not just because it implied England had a role in human origins. Piltdown Man’s features fit with the British establishment’s view of human evolution, in which a big brain was the first trait to distinguish human ancestors from other apes.

So when Dart announced that he had found a small-brained bipedal ape with humanlike teeth in the southern tip of Africa, scientists were primed to be skeptical, says Paige Madison, a historian of science at the Natural History Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen. Scientists were also skeptical of Dart. While a student in London, he had earned a reputation as a “scientific heretic, given to sweeping claims,” according to a paper coauthored by a colleague.

But initial criticism focused mostly on practical concerns, says Madison, who has studied the skeptics’ reactions. “I found what they were actually saying on paper to be quite reasonable.”

A big problem: Dart’s fossil was of a 3- or 4-year-old child. Critics pointed out that a young ape tends to resemble humans in some ways, but the similarities disappear as the ape matures. Critics also complained that Dart hadn’t done proper comparative analyses with young chimps and gorillas, and he refused to send the fossil to England where such analyses could be done. This refusal irked the British old guard. “It was unpalatable to the scientists in England that the young colonial upstart had presumed to describe the skull himself,” one of Dart’s contemporaries later wrote, “instead of submitting it to his elders and betters.”

It’s hard not to wonder how the era’s colonialist and racist attitudes shaped perceptions. The Taung Child came to light at a time when eugenics was still considered legitimate science, and much of anthropology was devoted to categorizing people into races and arranging them into hierarchies. On the one hand, Western researchers tended to maintain the perverse notion that Africans are more primitive than other people, even less evolved. On the other, they wanted to believe Europe or Asia is where humans originated.

How these views influenced reactions to the Taung Child is not clear-cut. Many skeptics didn’t cite the fossil’s location as a problem, and some acknowledged humans could have evolved in Africa. But deep-seated biases may have made it easier for some researchers to reject the Taung Child and accept Piltdown Man, even though fossil evidence for that claim was also scant, says Sheela Athreya, a paleoanthropologist at Texas A&M University in College Station.

Newspapers worldwide followed the Taung Child controversy. And while fans sent Dart poems and short stories casting the child as a national hero, he also received letters from disapproving creationists.

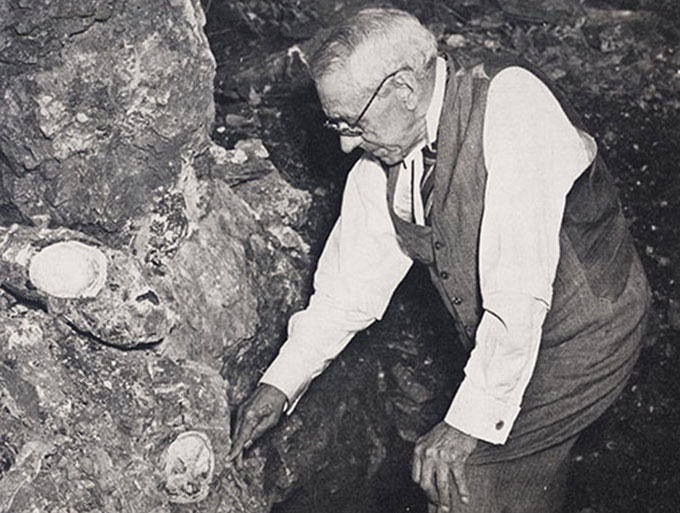

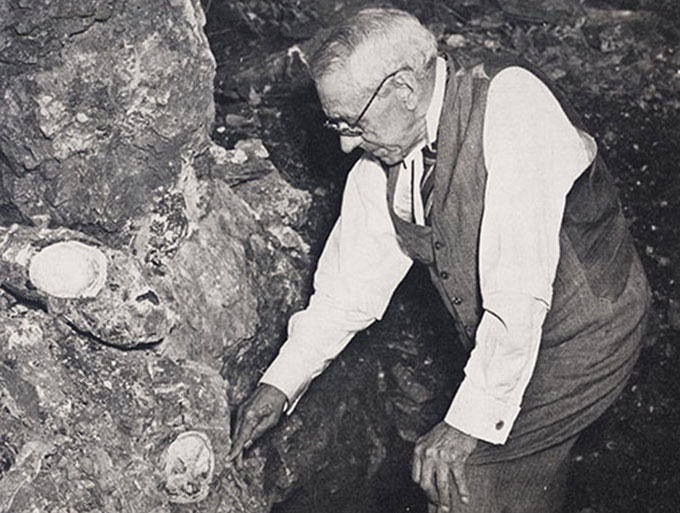

Amid it all, Dart had convinced at least one well-known scientist. Robert Broom, a Scottish-born physician living in South Africa and an authority on reptile evolution, recognized that fossils of fully grown A. africanus individuals would be needed to confirm that the Taung Child’s humanlike qualities were retained in adulthood.

In the 1930s and ’40s, Robert Broom unearthed fossils in South African caves, including at Sterkfontein (shown), that helped convince skeptics that Australopithecus was a human ancestor.

NATURAL HISTORY, 1947 (LINDA HALL LIBRARY)

Broom began to find just that evidence in 1936 in caves not far from Johannesburg. Often taking the heavy-handed approach of detonating dynamite to free specimens, he amassed a collection of fossils representing both the young and the old. Limb, spine and hip bones confirmed South Africa was once home to a bipedal ape, and skull bones verified Dart’s inferences about A. africanus’ humanlike teeth.

Even the staunchest Dart doubters couldn’t overlook this evidence. British anatomist Arthur Keith, who had once called Dart’s assertions “preposterous,” conceded. “I am now convinced,” he wrote in a one-paragraph letter to Nature in 1947, “that Prof. Dart was right and that I was wrong; the Australopithecinae are in or near the line which culminated in the human form.”

A few years later, in 1953, researchers exposed Piltdown Man to be a hoax — someone had planted a modern human skull alongside an orangutan jaw with its teeth filed down. Many experts outside of England had never been convinced by the find in the first place. “It was not a complete surprise when he was proved to be a fake,” Science News Letter reported.

Still, Africa’s role in human evolution was not cemented. From the time of the Taung Child’s unearthing through World War II, discoveries of hominin fossils continued in Indonesia and at a cave site near Beijing called Zhoukoudian. These fossils kept the focus on Asia

.

Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania’s eastern Serengeti Plains was home to a lake millions of years ago. Nearby volcanic eruptions helped preserve fossils at the site and enable dating of the finds.

A series of surprises

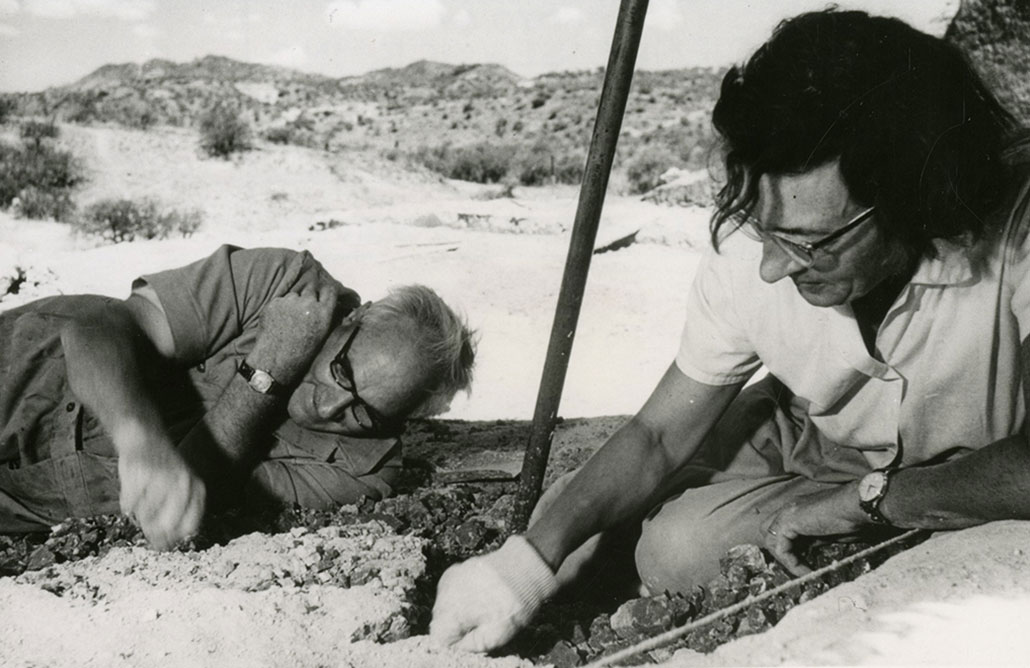

It was ultimately a series of discoveries by the husband-wife paleoanthropologists Louis and Mary Leakey that shifted the focus. Louis, who had grown up in East Africa as the son of English missionaries, had long believed Africa was the human homeland. While Broom was scouring South Africa in the 1930s, the Leakeys began exploring Olduvai Gorge in what is now Tanzania.

Year after year, the pair failed to find hominin fossils. But they dug up stone tools, suggesting that hominins must have lived there. So they kept looking. One day in 1959, while an ill Louis stayed behind in camp, Mary discovered a skull with small canine teeth like Australopithecus. But the fossil’s giant molar teeth, flaring cheekbones and bony crest running along the top of the skull where massive chewing muscles would have attached suggested something else. Nicknamed Nutcracker Man for its chompers, the species was dubbed Zinjanthropus boisei (it’s now called Paranthropus boisei because it is clearly a close cousin of P. robustus, a South African species found by Broom).

Louis and Mary Leakey spent decades digging in East Africa’s Olduvai Gorge (above) before finding hominin fossils. Their luck changed in 1959 when Mary found a skull belonging to an ancient human relative now known as Paranthropus boisei (below).

ACC. 90-105 – SCIENCE SERVICE, RECORDS, 1920S-1970S, SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION ARCHIVES/FLICKR

Paranthropus boisei

HUMAN ORIGINS PROGRAM, NMNH, SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION

Until the Zinjanthropus discovery, determining a hominin fossil’s age was largely a guessing game because there was no good way to measure how long ago an ancient fossil had formed. But advances in nuclear physics in the early and mid-20th century led to radioactive dating techniques that allowed age calculations. Using potassium-argon dating, geologists reported in 1961 that Zinjanthropus came from a rock layer about 1.75 million years old. The fossil was three times older than the Leakeys initially suspected. (Later, A. africanus proved to be even older, living about 2 million to 3 million years ago.) The discovery vastly stretched the timescales on which researchers were mapping human evolution.

The surprises didn’t end there. In the early 1960s, the Leakeys’ team recovered fossils of a hominin that lived at roughly the same time as Zinjanthropus but had smaller, more humanlike teeth and a brain notably bigger than that of both Zinjanthropus and Australopithecus. Because of the elevated brain size and details of the hand, the Leakeys argued that this hominin was the one who made the tools at Olduvai Gorge; in 1964, Louis and colleagues placed it in the human genus with the name Homo habilis, or handy man.

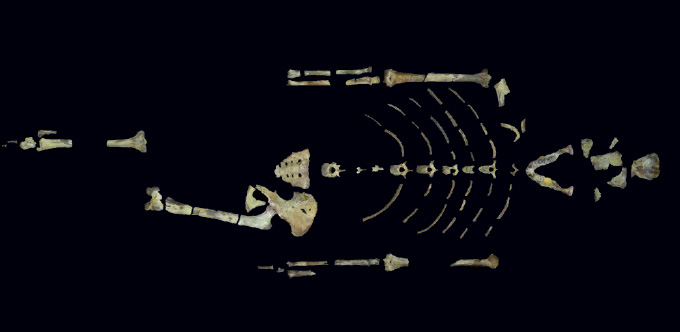

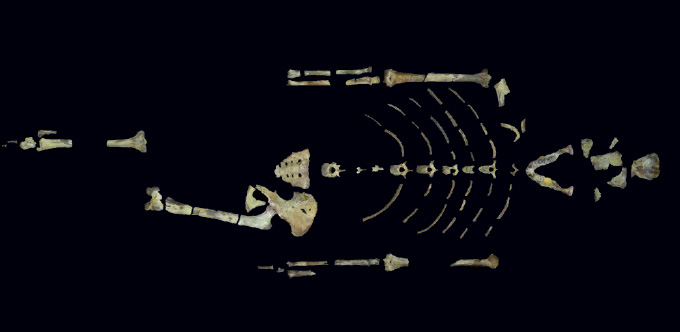

The Homo designation was controversial, and to this day paleoanthropologists debate how to classify these fossils. Still, the discoveries at Olduvai Gorge kicked off a paleo-anthropological gold rush in Africa. A 1974 discovery in Ethiopia, for instance, once again expanded the timescale of human evolution. It was one of the most famous discoveries in all of human evolution: the nearly 40 percent complete skeleton of Lucy, known more formally as Australopithecus afarensis, who lived about 3.2 million years ago.

Since then, researchers have shown repeatedly that the hominin fossil record stretches farthest back in Africa. Today, the oldest purported hominins date back some 6 million or 7 million years — to around the time when the ancestors of humans and chimpanzees probably parted ways.

The skeleton known as Lucy, discovered in Ethiopia in 1974, helped confirm that our ancient ancestors evolved upright walking long before big brains.

JOHN KAPPELMAN/UNIV. OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN

On the origin of our species

Even after it became clear that hominins originated in Africa, it was still uncertain where our species, Homo sapiens, began. By the 1980s, paleoanthropologists had largely settled into two camps. One side claimed that, like the earliest hominins, modern humans came from someplace in Africa. The other side championed a more diffuse start across Africa, Asia and Europe.

That same decade saw researchers increasingly relying on genetics to study human origins. Initially, scientists looked to modern people’s DNA to make inferences about ancient populations. But by the late 1990s, geneticists pulled off a feat straight out of science fiction: decoding DNA preserved in hominin fossils.

For paleoanthropologists, studying ancient DNA has been like astronomers getting a new telescope that sees into deep space with a new wavelength of light. It’s revealing things no one even thought to look for, says paleoanthropologist John Hawks of the University of Wisconsin–Madison. “That is the most powerful thing that genetics has handed us.”

And it’s revealed a truly tangled tale.

A trellis or a candelabra

Long before the rise of genetics, or even the discovery of many hominin fossils, unraveling human origins was a quest to explain how the world’s different races came to be. But after the horrors of World War II, anthropologists started to question the validity of race.

“This was a real moral hinge point in the science,” Hawks says. “It was a realization that viewing things through the perspective of race was creating evils in the world.” And it was scientifically dubious, as genetic evidence has shown that people are all so similar that race is more of a cultural concept than a biological phenomenon. Humans, in fact, are less genetically diverse than chimps.

As race was de-emphasized in the 1940s and ’50s, anthropologists started to think more about the mechanisms of evolution and how populations change over time, a direct influence of the “modern synthesis” that had united Darwinian evolution and genetics.

One influential forerunner to this period was anatomist and anthropologist Franz Weidenreich. After leaving Nazi Germany in the 1930s, he ended up in China studying fossils known as Peking Man (now classified as H. erectus), who lived several hundred thousand years ago. Weidenreich noticed that Peking Man shared certain features, such as shovel-shaped incisor teeth, with some present-day East Asians.

From this observation of apparent regional continuity across time, he concluded there had never been just one real-life Garden of Eden. As he wrote in 1947, “Man has evolved in different parts of the old world.”

Rather than picturing a family tree with one main trunk and branches, he envisioned human evolution as a trellis. Vertical lines represented groups of humans from different geographic regions, with the crisscrossing lines of the lattice representing mating between groups. Such gene flow enabled ancient forms across Africa, Asia and Europe to stay a unified species that gradually evolved into modern humans, with some regional variation maintained.

One consequence of all that mixing: “Pure” races never existed.

But a minority of researchers clung to the idea that race was central to understanding human evolution. In 1962, American anthropologist Carleton Coon transformed Weidenreich’s trellis into a candelabra, trimming away the intersecting lines. He argued that modern races stemmed from a common ancestor, but different lines independently evolved into H. sapiens, with races crossing the “sapiens” boundary at different times. In his view, Science News Letter explained, “the Negro race is at least 200,000 years behind the white race on the ladder of evolution.”

It’s a deeply disturbing statement to type today, and it was rejected by many at the time. Coon published his claims during the height of the U.S. civil rights movement, less than a year before Martin Luther King Jr. stood on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial and shared his dream of racial equality. Advocates of segregation cited the supposed evidence of inferiority to justify their racist agenda. But many experts discounted Coon’s views. It’s an “extreme opinion,” one anthropologist told Science News Letter in 1962, lacking “evidence of any nature to support it.”

Still, Coon’s claims tarnished Weidenreich’s view of human evolution. And in the 1960s and ’70s, interest shifted to much earlier stages of hominin history, many millions of years ago.

Homo sapiens arrives, somehow

In the mid-1980s, anthropologists went back to disentangling the roots of H. sapiens. By then, a basic picture had emerged: Hominins arose in Africa, and H. erectus was the first to venture outside of it, by what we now know was nearly 2 million years ago. In some places, H. erectus persisted for a long time; elsewhere, new groups appeared, such as Neandertals (H. neanderthalensis) in Europe and Asia. At some point, somehow, H. sapiens arrived and its predecessors vanished.

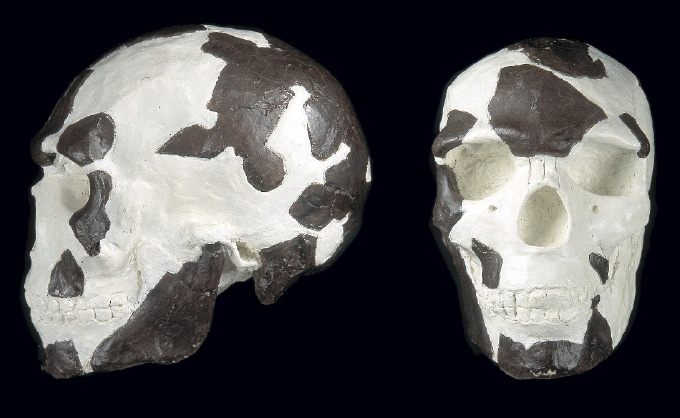

T.D. WHITE ET AL/NATURE 2003

Some of the oldest fossils classified as Homo sapiens still lack some features typical of people today. For instance, a roughly 300,000-year-old skull (top) from Jebel Irhoud in Morocco has a relatively long, flat braincase. Only later does a tall, rounded braincase appear to evolve, as seen in a 195,000-year-old skull (middle, white fills in missing pieces) from Omo Kibish and a 160,000-year-old skull (bottom) from Herto, both in Ethiopia.

That “somehow” became a matter of debate in the 1980s, ’90s and into the 2000s.

Milford Wolpoff, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, and colleagues revived the latticework of Weidenreich’s trellis model in the 1980s. Under this “multiregional” view, it was difficult to draw a clean line between the end of H. erectus and the beginning of H. sapiens. In fact, Wolpoff argued that H. erectus and other seemingly distinct groups should be folded into our species. Through intergroup mating these earlier “archaic” H. sapiens gradually evolved the features of “anatomically modern” humans.

Critics doubted there could have been enough intergroup mating back then to allow a small, globally scattered population to remain as one. Chris Stringer, a paleoanthropologist at the Natural History Museum in London, and colleagues proposed instead that H. sapiens originated in just one place — descending from H. erectus or a subsequent species — and then spread across the world. Along the way, these humans replaced other hominins, including Neandertals.

Both theories were difficult to test. For instance, the single-origin idea predicted that the oldest modern human fossils should all be found in just one region. But there weren’t many well-dated fossils from the relevant time period. And seeing ourselves in the fossil record proved challenging. Researchers disagreed on what features defined modern humans. A globular head? A flat face? Something as banal as a chin? These disagreements meant researchers on both sides could often look at the same fossil data and claim support for their position.

Genetic revolution

By the 1980s, DNA offered a new way to investigate the deep past. In 1987, one genetic study shifted momentum toward the single-origin theory, with Africa as the point of origin.

Researchers at the University of California, Berkeley analyzed mitochondrial DNA from people around the world. Because it’s inherited from mother to child and undergoes no genetic reshuffling, mitochondrial DNA preserves a record of maternal ancestry. African populations showed the greatest genetic diversity. And when the team built a family tree using the genetic data, it had two main branches: One held only African lineages and the other contained lineages from all over the world, including Africa. This pattern suggested the “mother” lineage came from Africa. Based on the estimated rate at which mitochondrial DNA accumulates changes, the team calculated that this African Eve lived about 200,000 years ago.

“Thus,” the team reported in Nature, “we propose that Homo erectus in Asia was replaced without much mixing with the invading Homo sapiens from Africa.”

Like fossils, genetic evidence is open to interpretation. Proponents of multiregional evolution pointed out that the African diversity may not be indicative of greater antiquity but simply a sign that African populations were much larger than other ancient groups. Mitochondrial DNA also isn’t a complete record of the past — given its unusual inheritance, lineages are easily lost over time.

Even with those warnings, the “Out of Africa” model gained followers as genetic evidence piled up. And in the late 1980s, 1990s and early 2000s, new dating techniques and discoveries suggested the earliest H. sapiens fossils came from Africa, at sites in Ethiopia dating to between 195,000 and 160,000 years ago. More recently, scientists linked roughly 300,000-year-old Moroccan fossils to H. sapiens.

A new window into the past opened in 1997. A team led by Svante Pääbo, a geneticist now at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, recovered mitochondrial DNA from a Neandertal fossil. It was so different from any modern human’s DNA that it suggested Neandertals must be a separate species. That was another blow to the multiregional model.

But paleoanthropology is like solving a jigsaw puzzle without all the pieces; any new piece can change the picture. That’s what happened in 2010. When Pääbo and colleagues assembled the Neandertal’s genetic blueprint, or genome, and compared it with modern human DNA, the team came to a startling conclusion: About 1 to 4 percent of DNA in non-Africans today came from Neandertals.

“We were naïve to think that humans just marched out of Africa, killed some Neandertals and populated the world,” archaeologist John Shea of Stony Brook University in New York later told Science News.

That genetic data seemed to support a compromise model between Out of Africa and multiregionalism. Yes, modern humans originated in Africa, the idea went, but once they expanded into new territories, they mated with other hominins. Hints of such hybridization had been reported in the late ’90s, when some researchers claimed an ancient skeleton from Portugal had a mix of Neandertal and human features.

Interbreeding wasn’t the only shock to come in 2010. Pääbo’s group also analyzed DNA from a finger bone found at Siberia’s Denisova Cave. Both Neandertals and modern humans had once lived there, but the DNA didn’t match either group. For the first time, genetics had revealed a new hominin. These Denisovans are still mysterious, known from only a few bits of bone and teeth, but they too interbred with humans. For instance, Denisovan DNA accounts for about 2 to 4 percent of Melanesian people’s genome.

It’s complicated

Over the last decade, as genetic and fossil revelations have painted a more complex picture of human origins, paleoanthropologists have moved beyond both the multiregional and simple Out of Africa scenarios. Rather than a tree with separate branches or a trellis, human evolution was probably more like a braided stream, a concept traced to paleoanthropologist Xinzhi Wu of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing, who used a river metaphor to describe patterns of human evolution in China. Different human populations may have emerged, with some floating away and petering out and others connecting to varying degrees.

One emerging view suggests that much of early human evolution occurred in Africa, but there was not one place on the continent where H. sapiens was born. Starting at least 300,000 years ago, modern H. sapiens features start to show up in the fossil record. But these features didn’t arise all together. Only through the mating of different populations across Africa did the suite of behavioral and biological traits that define us today crystallize, says Eleanor Scerri, an evolutionary archaeologist at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena, Germany.

“Our origins lie in the interactions of these different populations,” she says. Understanding those interactions is limited by how little of ancient Africa researchers have explored so far. Western, central and much of northern Africa are terra incognita.

There’s still much to explore in other parts of the world too. A single, unifying explanation of human origins may not be possible, as different evolutionary processes probably shaped human history in different regions, says Athreya, of Texas A&M University.

Making more progress on understanding those processes and our roots will come from new discoveries, technological advances and, importantly, new perspectives. For the last 100 years, our origin story has been told by mostly white, mostly male scientists. Welcoming a more diverse group of researchers into paleoanthropology, Athreya says, will reveal blind spots and biases as scientists add to and amend the tale.

This is, after all, everyone’s story.

About Erin Wayman is the magazine managing editor. She has a master’s degree in biological anthropology from the University of California, Davis and a master’s degree in science writing from Johns Hopkins University.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/8557761/Palantiri.jpg) '

'