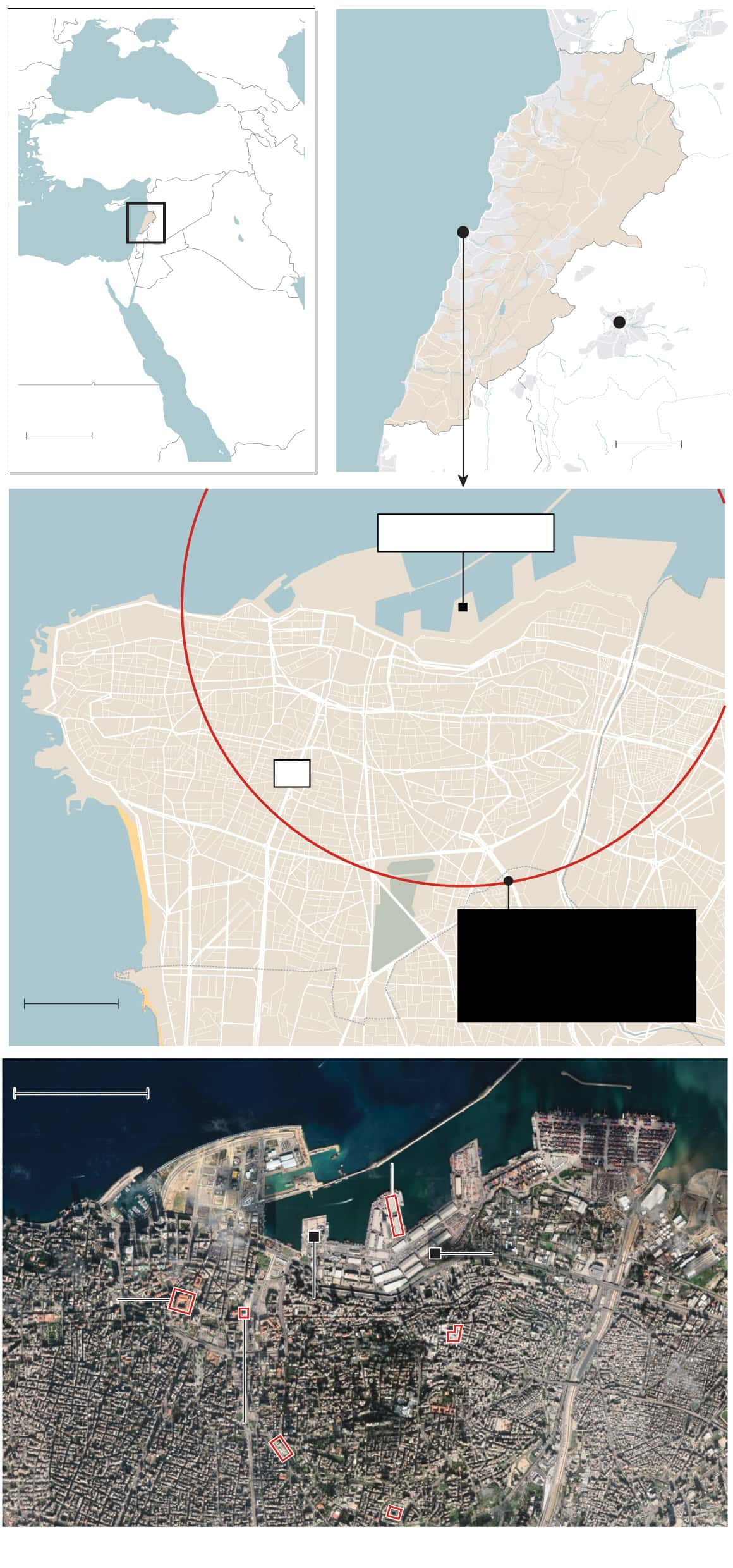

Part of Beirut silo complex collapses after fire, following devastating 2020 port blast

Silos damaged in waterfront explosion that killed over 200 and injured thousands

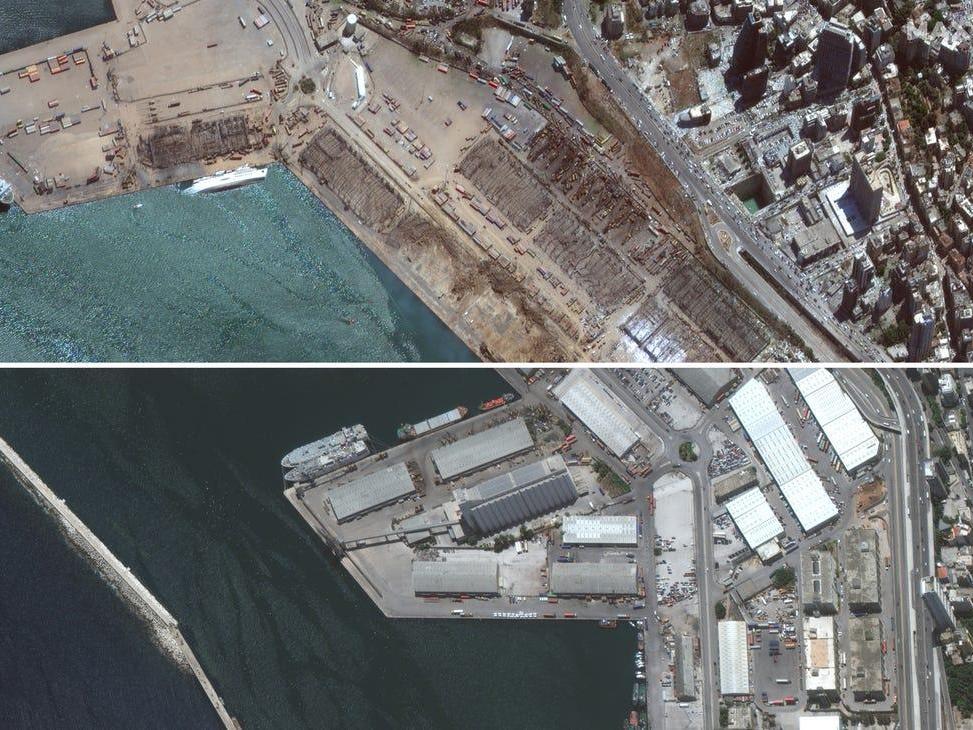

A section of Beirut's massive port grain silos, shredded in the 2020 explosion, collapsed in a huge cloud of dust on Sunday after a weeks-long fire triggered by grains that had fermented and ignited in the summer heat.

The northern block of the silos collapsed after what sounded like an explosion, kicking up thick grey dust that enveloped the iconic structure and the port next to a residential area. It was not immediately clear if anyone was injured.

Assaad Haddad, the general director of the Port Silo, told The Associated Press that "everything is under control" but that the situation has not subsided yet. Minutes later, the dust settled and calm returned.

However, Youssef Mallah, from the Civil Defence department, said that other parts of the northern block of the silos were at risk and that other sections of the giant ruin could collapse.

The 50 year-old, 48-metre-tall giant silos withstood the force of the explosion two years ago, effectively shielding the western part of Beirut from the chemical blast that killed over 200 people, wounded more than 6,000 and badly damaged entire neighbourhoods.

In July, a fire broke out in the northern block of the silos due to the fermenting grains. Firefighters and Lebanese Army soldiers were unable to put it out and it smouldered for weeks, a nasty smell spreading around. The environment and health ministries last week issued instructions to residents living near the port to stay indoors in well-ventilated spaces.

The fire and the dramatic sight of the smouldering, partially blackened silo revived the memories and in some cases, the trauma for the survivors of the gigantic explosion that tore through the port two years ago.

People rush indoors after collapse

Many rushed to close windows and return indoors after the collapse Sunday.

Emmanuel Durand, a French civil engineer who volunteered for the government-commissioned team of experts, told the AP that the northern block of the silo was already been tipping since the day of the 2020 blast, but the latest fire had weakened its frail structure, accelerating a possible collapse.

When the fermenting grains ignited earlier in July, firefighters and Lebanese soldiers tried to put out the fire with water, but withdrew after the moisture made it worse. The Interior Ministry said over a week later that the fire had spread, after reaching some electric cables nearby.

The silos continued smoldering for weeks as the odour of fermented grain seeped into nearby neighbourhoods. Residents who had survived the 2020 explosion said the fire and the smell reminded them of their trauma. The environment and health ministries last week instructed residents living near the port to stay indoors in well-ventilated spaces.

The Lebanese Red Cross distributed K-N95 masks to those living nearby, and officials ordered firefighters and port workers to stay away from the immediate area near the silos.

Engineer says collapse was inevitable

Emmanuel Durand, a French civil engineer who volunteered for the government-commissioned team of experts, told the AP earlier in July that the northern block of the silo had been slowing tilting over time but that the recent fire accelerated the rate and caused irreversible damage to the already weakened structure.

Durand been monitoring the silos from thousands of kilometres away using data produced by sensors he installed over a year ago, and updating a team of Lebanese government and security officials on the developments in a WhatsApp group. In several reports, he warned that the northern block could collapse at any moment.

Last April, the Lebanese government decided to demolish the silos, but suspended the decision following protests from families of the blast's victims and survivors. They contend that the silos may contain evidence useful for the judicial probe, and that it should stand as a memorial for the tragic incident.

The Lebanese probe has revealed that senior government and security officials knew about the dangerous material stored at the port, though no officials have been convicted thus far. The implicated officials subsequently brought legal challenges against the judge leading the probe, which has left the investigation suspended since December.

By Issam Abdallah, Yara Abi Nader, Laila Bassam and Timour Azhari

07/31/22

Part of the grain silos at Beirut Port collapsed on Sunday just days before the second anniversary of the massive explosion that damaged them, sending a cloud of dust over the capital and reviving traumatic memories of the blast that killed more than 215 people.

There were no immediate reports of injuries.

Lebanese officials warned last week that part of the silos - a towering reminder of the catastrophic Aug. 4, 2020 explosion - could collapse after the northern portion began tilting at an accelerated rate.

"It was the same feeling as when the blast happened, we remembered the explosion," said Tarek Hussein, a resident of nearby Karantina area, who was out buying groceries with his son when the collapse happened. "A few big pieces fell and my son got scared when he saw it," he said.

A fire had been smoldering in the silos for several weeks which officials said was the result of summer heat igniting fermenting grains that have been left rotting inside since the explosion.

The 2020 blast was caused by ammonium nitrate unsafely stored at the port since 2013. It is widely seen by Lebanese as a symbol of corruption and bad governance by a ruling elite that has also steered the country into a devastating financial collapse.

One of the most powerful non-nuclear blasts on record, the explosion wounded some 6,000 people and shattered swathes of Beirut, leaving tens of thousands of people homeless.

Ali Hamie, the minister of transport and public works in the caretaker government, told Reuters he feared more parts of the silos could collapse imminently.

Environment Minister Nasser Yassin said that while the authorities did not know if other parts of the silos would fall, the southern part was more stable.

The fire at the silos, glowing orange at night inside a port that still resembles a disaster zone, had put many Beirut residents on edge for weeks.

'REMOVING TRACES' OF AUG. 4

There has been controversy over what do to with the damaged silos.

The government took a decision in April to destroy them, angering victims' families who wanted them left to preserve the memory of the blast. Parliament last week failed to adopt a law that would have protected them from demolition.

Citizens' hopes that there will be accountability for the 2020 blast have dimmed as the investigating judge has faced high-level political resistance, including legal complaints lodged by senior officials he has sought to interrogate.

Prime Minister-designate Najib Mikati has said he rejects any interference in the probe and wants it to run its course.

However, reflecting mistrust of authorities, many people have said they believed the fire was started intentionally or deliberately not been contained.

Divina Abojaoude, an engineer and member of a committee representing the families of victims, residents and experts, said the silos did not have to fall.

"They were tilting gradually and needed support, and our whole goal was to get them supported," she told Reuters.

"The fire was natural and sped things up. If the government wanted to, they could have contained the fire and reduced it, but we have suspicions they wanted the silos to collapse."

Reuters could not immediately reach government officials to respond to the accusation that the fire could have been contained.

Earlier this month, the economy minister cited difficulties in extinguishing the fire, including the risk of the silos being knocked over or the blaze spreading as a result of air pressure generated by army helicopters.

Fadi Hussein, a Karantina resident, said he believed the collapse was intentional to remove "any trace of Aug. 4".

"We are not worried for ourselves, but for our children, from the pollution," resulting from the silos' collapse, he said, noting that power cuts in the country meant he was unable to even turn on a fan at home to reduce the impact of the dust.

(Writing by Nayera Abdallah and Tom PerryEditing by Hugh Lawson, Nick Macfie and Frances Kerry)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/LZN3CBALERIGDBU7UKBMAJJBBM.jpg)