Special report: Speaking to Lebanese port officials, government sources, firefighters and eyewitnesses, and reviewing a dozen documents, Bel Trew, Oliver Carroll, Samira el-Azar and Richard Hall trace the paper trail of negligence and incompetence that led up to the devastating explosion

A helicopter puts out a fire at the scene of the explosion at the port of Lebanon’s capital ( AFP/Getty )

The Independent employs reporters around the world to bring you truly independent journalism. To support us, please consider a contribution.

Residents across central Beirut were peering quizzically at a mushroom cloud of grey above their heads when the sky cracked open and a tidal wave of pressure roared through.

It was like sound itself had imploded in everyone’s ears. The world simultaneously broke apart and snapped shut. Bodies were pulled into the air and thrown across rooms and streets. The facades of apartment blocks, offices and hospitals were peeled off and chewed into pieces.

The explosion unleashed warring tornadoes of pressure that wrestled everything off the walls and the floors, spitting shrapnel that cut through the air like bullets. The power of the blast instantly eviscerated windows, smacked down buildings, crumpled steel shutters and crushed cars like a giant’s fist.

“It was like an atomic bomb,” says Hala Okeili, 33, a yoga instructor who was less than a mile away from the port when disaster struck. “I thought they had started a war and someone was bombing us.”

The blast, which struck the Lebanese capital around 6.08pm on Tuesday, is being called one of the largest non-nuclear explosions in modern history. It killed at least 210 people, and injured 6,000 more. Dozens are still missing.

Investigations into what happened and who is responsible are underway: initial analysis points to nearly 3,000 tons of dangerously stored explosive ammonium nitrate catching on fire.

Watch more

Entire Lebanon government resigns amid fury over explosion

A review of a dozen documents as well as interviews with Lebanese port officials, government sources, firefighters and eyewitnesses showed enormous incompetence in both the seven years leading up to the blast and the final 13 minutes before the city was destroyed.

Since 2014 authorities had so often warned about the dangerous nature of the materials being stored at the port that it became common practice to avoid Hangar 12, where the ammonium nitrate was being stored. Port officials may have even left the scene before they could brief first responders about the nature of the substances.

The firefighters, all of them thought to have died in the blast, arrived with inadequate provisions to put out the smouldering fire which may have started with fireworks.

The need for answers as to why it happened is urgent.

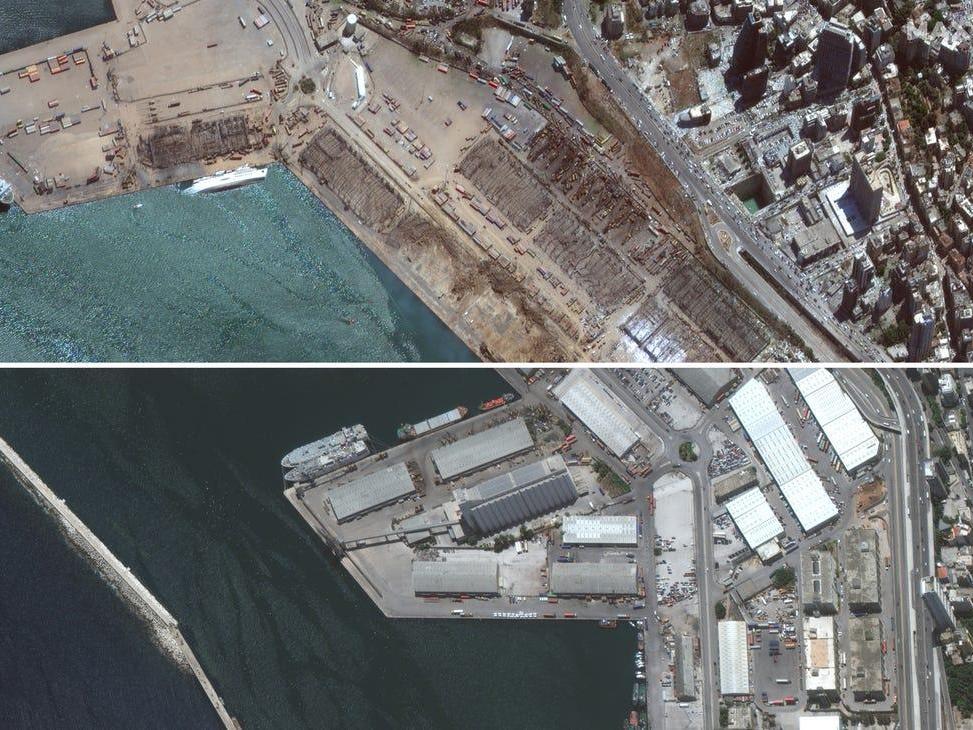

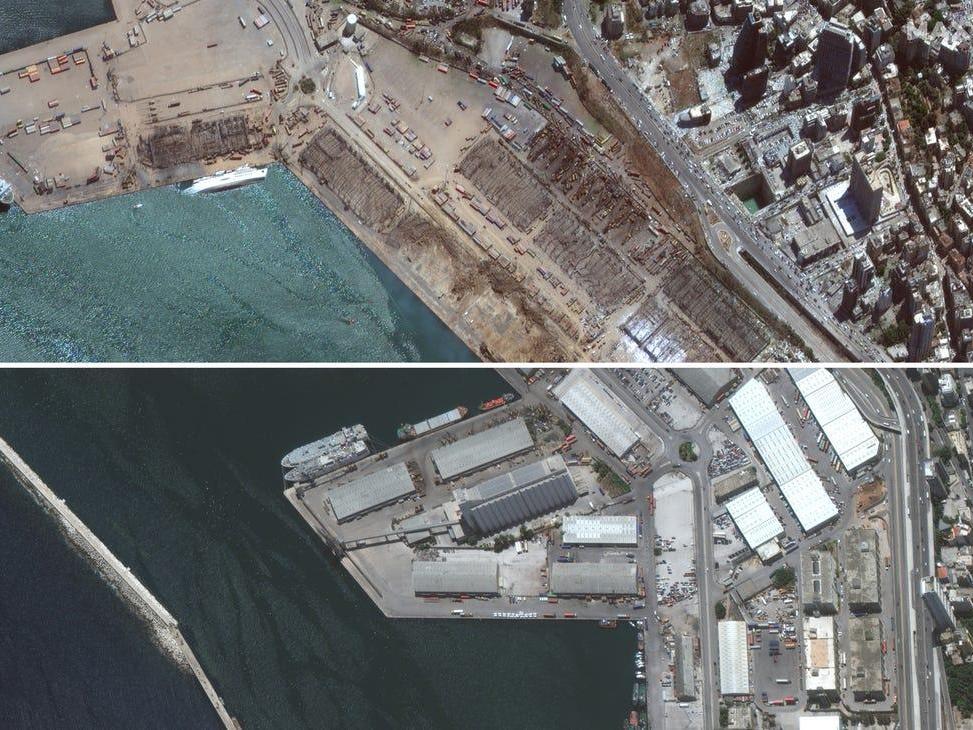

Beirut port, before and after Tuesday’s explosion (Maxar Technologies)

The boat that was lost

None of the crew aboard the Russian-owned ship would have guessed seven years ago that their journey, which started in the Black Sea, would ultimately end with the decimation of the Lebanese capital of Beirut more than 1,000km away.

The story began on 23 September 2013. The Rhosus, a 27-year-old cargo ship, set sail from the Georgian port of Batumi with a 2750-ton cargo of ammonium nitrate, an explosive substance frequently used in fertilisers and bombs.

The ship was never supposed to dock in Beirut. A landing docket given to The Independent shows the intended end recipient was an explosives company in Mozambique.

The vessel’s origins are shadowy, like much in the global shipping industry. It was managed by a company registered in the Marshall Islands, and set sail under a Moldovan flag. It was controlled by a small-scale Russian businessman and Cyprus resident named Igor Grechushkin, according to documents reviewed by The Independent.

Russian citizen Boris Prokoshev eventually took charge of the vessel when it made a stop in Tuzla, Turkey.

Trouble was already brewing aboard the ship.

Captain Prokoshev and crew members demand their release from the arrested cargo vessel in 2014 (Reuters)

Captain Prokoshev was greeted by an entirely new Ukrainian crew after the old one unexpectedly stormed out because they had not been paid for four months.

But it was only when the Prokoshev finally met the owner in Pireaus, Greece, during an October fuel stop, that he began to understand the scale of Grechushkin’s financial problems.

“It was bizarre – after first signing off on the supplies, he then refused to pay for two-thirds of them,” Prokoshev tells The Independent. “Then he ordered us to make an additional stop in Beirut to pick up another consignment.”

The Rhosus set sail for Beirut on 15 November and arrived, in the captain’s estimation, approximately four days later. The exact circumstances before landing are disputed. According to lawyers acting for creditors of the vessel, the Rhosus experienced technical problems forcing it to enter the port, where it then failed a safety inspection.

The Rhosus is seen in Volos, Greece (AP)

But Prokoshev tells The Independent he was able to dock in Beirut to take on an extra load of heavy road-making equipment, which he eventually decided could not safely be stowed onboard. Following a “heated” discussion with Grechushkin, the captain agreed to travel on to Larnaca in Cyprus.

But by this point, Lebanese port officials were demanding unpaid fines and port fees, and refused to let them leave. In Prokoshev’s account, Grechushkin then made a decision to “abandon” the ship and its 10-man crew to their fate. Some time in late November, Lebanese authorities impounded the vessel.

The crew quickly ran out of provisions. “If it wasn’t for our Beirut agent, we’d have starved,” Prokoshev tells The Independent.

‘Dangerous’ cargo left behind

After months of furious lobbying by Ukranian diplomats, the majority of the Rhosus crew was allowed to return home in early 2014. But Prokoshev and a skeleton staff were kept on, effectively held hostage by Lebanese authorities as they worked out what to do with the ship.

The captain was even forced to sell off the fuel to pay for lawyers, who applied for the crew’s release on “compassionate grounds”. A Lebanese court eventually agreed, but only after taking consideration of the “imminent danger the crew was facing given the nature of the cargo”.

By the time of their release, the crew was owed over $240,000 (£190,600) in unpaid wages.

The Lebanese authorities knew from the very start just how volatile the shipment was. The next six years were marked by numerous warnings that could have averted disaster had they been acted upon. Instead, a toxic mix of corruption and mismanagement that plagues every public institution in Lebanon paved the way for tragedy.

Read more

A review of a dozen documents as well as interviews with Lebanese port officials, government sources, firefighters and eyewitnesses showed enormous incompetence in both the seven years leading up to the blast and the final 13 minutes before the city was destroyed.

Since 2014 authorities had so often warned about the dangerous nature of the materials being stored at the port that it became common practice to avoid Hangar 12, where the ammonium nitrate was being stored. Port officials may have even left the scene before they could brief first responders about the nature of the substances.

The firefighters, all of them thought to have died in the blast, arrived with inadequate provisions to put out the smouldering fire which may have started with fireworks.

The need for answers as to why it happened is urgent.

Beirut port, before and after Tuesday’s explosion (Maxar Technologies)

The boat that was lost

None of the crew aboard the Russian-owned ship would have guessed seven years ago that their journey, which started in the Black Sea, would ultimately end with the decimation of the Lebanese capital of Beirut more than 1,000km away.

The story began on 23 September 2013. The Rhosus, a 27-year-old cargo ship, set sail from the Georgian port of Batumi with a 2750-ton cargo of ammonium nitrate, an explosive substance frequently used in fertilisers and bombs.

The ship was never supposed to dock in Beirut. A landing docket given to The Independent shows the intended end recipient was an explosives company in Mozambique.

The vessel’s origins are shadowy, like much in the global shipping industry. It was managed by a company registered in the Marshall Islands, and set sail under a Moldovan flag. It was controlled by a small-scale Russian businessman and Cyprus resident named Igor Grechushkin, according to documents reviewed by The Independent.

Russian citizen Boris Prokoshev eventually took charge of the vessel when it made a stop in Tuzla, Turkey.

Trouble was already brewing aboard the ship.

Captain Prokoshev and crew members demand their release from the arrested cargo vessel in 2014 (Reuters)

Captain Prokoshev was greeted by an entirely new Ukrainian crew after the old one unexpectedly stormed out because they had not been paid for four months.

But it was only when the Prokoshev finally met the owner in Pireaus, Greece, during an October fuel stop, that he began to understand the scale of Grechushkin’s financial problems.

“It was bizarre – after first signing off on the supplies, he then refused to pay for two-thirds of them,” Prokoshev tells The Independent. “Then he ordered us to make an additional stop in Beirut to pick up another consignment.”

The Rhosus set sail for Beirut on 15 November and arrived, in the captain’s estimation, approximately four days later. The exact circumstances before landing are disputed. According to lawyers acting for creditors of the vessel, the Rhosus experienced technical problems forcing it to enter the port, where it then failed a safety inspection.

The Rhosus is seen in Volos, Greece (AP)

But Prokoshev tells The Independent he was able to dock in Beirut to take on an extra load of heavy road-making equipment, which he eventually decided could not safely be stowed onboard. Following a “heated” discussion with Grechushkin, the captain agreed to travel on to Larnaca in Cyprus.

But by this point, Lebanese port officials were demanding unpaid fines and port fees, and refused to let them leave. In Prokoshev’s account, Grechushkin then made a decision to “abandon” the ship and its 10-man crew to their fate. Some time in late November, Lebanese authorities impounded the vessel.

The crew quickly ran out of provisions. “If it wasn’t for our Beirut agent, we’d have starved,” Prokoshev tells The Independent.

‘Dangerous’ cargo left behind

After months of furious lobbying by Ukranian diplomats, the majority of the Rhosus crew was allowed to return home in early 2014. But Prokoshev and a skeleton staff were kept on, effectively held hostage by Lebanese authorities as they worked out what to do with the ship.

The captain was even forced to sell off the fuel to pay for lawyers, who applied for the crew’s release on “compassionate grounds”. A Lebanese court eventually agreed, but only after taking consideration of the “imminent danger the crew was facing given the nature of the cargo”.

By the time of their release, the crew was owed over $240,000 (£190,600) in unpaid wages.

The Lebanese authorities knew from the very start just how volatile the shipment was. The next six years were marked by numerous warnings that could have averted disaster had they been acted upon. Instead, a toxic mix of corruption and mismanagement that plagues every public institution in Lebanon paved the way for tragedy.

Read more

World leaders pledge €250m to help Lebanon after Beirut explosion

The first warning was raised before the cargo was even offloaded in an internal memo dated February 2014 and seen by The Independent.

In it Colonel Joseph Skaf, head of the Lebanese narcotics control division, warned Beirut’s anti-smuggling department that the material was “highly dangerous and a threat to public safety”.

Baroudi & Associates, which represented the Russian vessel’s crew, reportedly sent letters in July 2014 to officials at Beirut port and the ministry of transportation “warning of the dangers of the materials carried on the ship”.

In the end shortly after the crew’s departure from Lebanon, the dangerous cargo was transferred to warehouse number 12.

The Rhosus, without crew or an owner, would remain in Beirut’s docks before sinking “two or three years later”.

For Prokoshev it was the end of a nightmare, and an event he had long shelved in his mind, until news broke of the blast last week. For the citizens of Beirut this would mark the start of theirs.

A damning paper trail

Six years on, it was common knowledge in Beirut’s port that Hangar 12 was “dangerous”, port employees told The Independent.

Not everyone knew exactly what was inside. The rank and file believed it housed confiscated weapons. People steered clear.

At the official level, the contents of the hangar were very well known. In fact concerns about the stockpile were raised at least eight times since 2014, according to documents seen by The Independent and interviews with officials.

Fireworks were even moved into the hangar, despite the dangers, according to one port source.

The paper trail is damning.

In a letter dated 20 May 2016, the then head of the customs department Shafik Merhi wrote to a judge at the Urgent Matters Court asking for permission to sell or export the dangerous stockpile to a Lebanese company. He mentions that it was jeopardising the safety of the port and the workers.

A year later in a 28 October 2017 letter to the same court, Badri Daher, the new head of the customs department, repeats the same plea.

In this communique, seen by The Independent, he writes that it follows similar letters sent in 2014, 2015, twice in 2016 and earlier in 2017. Shortly before his arrest, Daher, who is among more than a dozen port officials currently under investigation, said he received no proper instructions of what to do.

In December 2019, the State Security requested an investigation into dangerous substances in Hangar 12 and completed its findings in January. It informed the presidency and the prime minister a few months later.

President Michel Aoun admitted that nearly three weeks before the blast – on 20 June – he was handed that report and informed that the dangerous material had been there for seven years.

He said he immediately ordered the military and security officials “to do what is needed”.

Prime Minister Hassan Diab, whose government resigned on Monday, received the same letter on the same day and sent it on to the Supreme Defence Council for advice within 48 hours.

But still nothing was done.

The matter was even raised just 11 days before the blast when the public works minister, Michel Najjar, told Al Jazeera he first learnt about the dangerous stockpile.

Because of a new coronavirus lockdown in place at the time, Najjar said there was a short delay and so he spoke to the port’s general manager, Hassan Koraytem, about the matter on the Monday 24 hours before the blast.

The port manager said he would send all the relevant documentation so everyone could look into the matter. But it was too late.

Thirteen minutes that sealed the city’s fate

On the afternoon of Tuesday 4 August, port electrician Joe Akiki, 23, called his mother to say he was starting the night shift.

Most of the port workers clock off at 4pm each day. And so there were comparatively few people on the ground when, a few hours later, a fire started.

Shortly before 6pm local time, Akiki stood on the roof of a building which was part of Beirut’s imposing grain silo. He started filming black smoke billowing out of warehouse 12, which was about 40m away in front of him.

In the clip, the camera pans across left to right across the battered hangar. Faint sirens, perhaps belonging to the incoming fire crew, can be heard sounding in the background.

Joe Akiki films the burning warehouse from on top of the silo minutes before the blast

Around the same time, at 5:55pm, a member of the fire department operations room just east of the port received a call from the Beirut police department saying there was a fire in one of the warehouses.

Fires at the port are not uncommon, he told The Independent. But the way it was reported and handled was unusual. The fire department employee who received the call said no one mentioned ammonium nitrate or explained to them which hangar was affected.

A 10-person team – nine male firefighters and female paramedic – was dispatched to the scene arriving just two minutes later.

There, unusually, there was no port crew to greet them, show them the site and hand them the key. It took them some time to work out the location of the fire.

Fire department officials told The Independent had they known the contents of the warehouse and its location or even been given a key, they would have had more time to assess the danger and the contents of the hanger, possibly put out the initial fire, order an evacuation or just scramble to safety.

Instead the firefighters wasted precious minutes that could have saved lives – their lives – trying to locate and break into the warehouse.

“Each minute counts in our work. If they just had more information,” said fire department chief Fadi Mazboudi.

At some point an unknown person, likely a port worker, began filming from the exact same spot where Akiki was standing. The clip that was shared online and verified by Bellingcat shows the smoke thickening to a deep charcoal. The crackle of dozens of what appear to be fireworks can be heard, popping in time with bright white and red sparks.

The person filming begins to retreat from the fire as it grows. A man screams as a large explosion sends them scrambling across the roof.

Across town, just before 6pm, that initial blast was heard by many residents who took to social media to tweet pictures of the column of smoke towering in the sky.

As the minutes trickled by more people came out of their homes, businesses, and shops, or looked out their window to find out what was going on.

Just 600m south of Hangar 12, Cherine el-Zein, an interior designer and activist, started filming the cloud above the port and telling people they should shut the doors and windows because of the smoke.

Cherine el-Zein films the moment the explosion destroys swathes of Beirut

A few minutes along Armenia Street to her right, Carmen Khoury, 46, a university administrator, stopped buying water and stepped out of the shop with a woman she did not know to look for fighter jets.

Back at Hanger 12, Sahar Fares, 27, the female medic accompanying the all-male fire crew had herself already started filming.

From the footage – broadcast by the BBC and verified by The Independent – it is possible to geolocate her to an area just below where Akiki was standing on top of the grain silo.

Her video shows the warehouse on fire, with her colleagues in uniform looking up at the burning building. She sent this clip to her fiance Gilbert Karaan at 6.03pm, according to Mazboudi. Worried, Gilbert spoke to her on the phone, urging her leave. He was still on the call when, disoriented, she started to run towards the grain silo.

A minute later at 6.04pm, Akiki, presumably scared and confused, sent his three-second clip with no explanation to a WhatsApp group chat: the last time his friends would ever hear from him.

By this point the firefighters realised the enormity of the situation that they had walked into blind. The fire was much bigger than they anticipated.

And so a few seconds before 6.08pm, firefighters Elia Khizami and Charbel Karam called their superiors demanding immediate back-up. They warned they only had “three tons of water” which wasn’t enough to control such a massive fire.

But before anyone within the fire department could scramble together a single piece of equipment, Hangar 12 detonated.

Fares was still on the phone to her fiance and running for safety when the line cut.

The sky above her imploded into a brilliant and billowing roar of orange and deep red, which set off a white ring of pressure consuming everything in its path.

The fire department employee who took the original phone call is thrown metres in the air in his office, which is ripped open.

For Carmen Khoury, just a few hundred metres away from the epicentre, it felt like hell had been unleashed.

“An iron rod swung down and knocked me off my feet. I found myself pinned under a car, with the woman beside me bleeding,” she says, describing the horrific moment.

“I have lived through two wars, and I have never experienced a blast quite like that. For a second I thought the world had come to an end.”

The city torn in two

For nearly one whole minute everything on Armenia street was quiet – in a kind of sharp inhalation of breath before the surge of pain.

Cherine el-Zein’s video capturing the moment is black; the only sounds heard are the hiss of gas and the persistent bleat of car alarms.

Then as people regain consciousness the screams start. The sirens begin.

“What just happened? My daughter is inside the shop, my daughter is inside the shop,” shouts one man in desperation. In the distance a woman says something incomprehensible and quietly whimpers.

Across Beirut, blood-soaked bodies staggered through the dust and smoke and glass and mess. Many asked themselves if a war had started.

View from the ocean of Beirut’s devastated port after warehouse explosion

Hala Okeili, who was approaching Armenia street in her car, says everything was instantly destroyed.

“Our neighbours, faces I recognised. Young people bleeding from every single part of their bodies.”

Citizens started making frantic phone calls to family members across the city. People report experiencing hour-long lapses in memory.

Medical workers at the nearest hospital St George, which was gutted by the blast, were forced to pull their own colleagues and patients from under the fallen masonry. With the emergency room destroyed, the generator broken and parts of the building structurally unsound, they started treating the newly injured in the car park with the light of their mobile phones.

Citizens on motorcycles began to ferry the shell-shocked injured, many hastily patched up by well-wishers, to hospitals outside the city, as those close to downtown Beirut were each capacity.

At the port, the explosion had clawed a 43m-deep crater, overturned cruise ships like beached whales, destroyed half of Lebanon’s main grain silo, and left just the rickety ribs of the warehouses.

Days later, rescue workers issued diminishing percentages of the likelihood of finding survivors there. Angry families gathered at the site demanding bulldozers check under the warehouses in case anyone made it an underground network of tunnels and store rooms.

In succession the bodies of Fares, Akiki and Khizami are found within the rubble, many of them incinerated and in pieces. But the rest of the team, including Karam, remain missing.

‘Hang up the nooses’

Very quickly in the aftermath of the blast, the shattered streets of Beirut begin to simmer with rage. Protesters armed with nooses demand accountability and help from their government whose officials are woefully absent in the rescue and clean-up operation manned by volunteers.

Among the crowds are Khoury and El-Zein, who protest despite having been hospitalised. The unidentified woman pinned under the car with Khoury doesn’t make it.

A nation’s grief turns to fury.

“There’s not one form of death they haven’t used with us,” says Sara Assaf, a Lebanese activist at one rally. She says this was no accident, but the result of years of endemic corruption at every level of public life by the country’s leaders.

“They killed us financially. They killed us economically. They killed us physically. They killed us morally. They killed us chemically.”

Since the explosion, everyone has passed the buck. President Aoun insisted on Friday he is not responsible, saying that he didn’t know where the ammonium nitrate was placed or “the level of danger”.

Watch more

The first warning was raised before the cargo was even offloaded in an internal memo dated February 2014 and seen by The Independent.

In it Colonel Joseph Skaf, head of the Lebanese narcotics control division, warned Beirut’s anti-smuggling department that the material was “highly dangerous and a threat to public safety”.

Baroudi & Associates, which represented the Russian vessel’s crew, reportedly sent letters in July 2014 to officials at Beirut port and the ministry of transportation “warning of the dangers of the materials carried on the ship”.

In the end shortly after the crew’s departure from Lebanon, the dangerous cargo was transferred to warehouse number 12.

The Rhosus, without crew or an owner, would remain in Beirut’s docks before sinking “two or three years later”.

For Prokoshev it was the end of a nightmare, and an event he had long shelved in his mind, until news broke of the blast last week. For the citizens of Beirut this would mark the start of theirs.

A damning paper trail

Six years on, it was common knowledge in Beirut’s port that Hangar 12 was “dangerous”, port employees told The Independent.

Not everyone knew exactly what was inside. The rank and file believed it housed confiscated weapons. People steered clear.

At the official level, the contents of the hangar were very well known. In fact concerns about the stockpile were raised at least eight times since 2014, according to documents seen by The Independent and interviews with officials.

Fireworks were even moved into the hangar, despite the dangers, according to one port source.

The paper trail is damning.

In a letter dated 20 May 2016, the then head of the customs department Shafik Merhi wrote to a judge at the Urgent Matters Court asking for permission to sell or export the dangerous stockpile to a Lebanese company. He mentions that it was jeopardising the safety of the port and the workers.

A year later in a 28 October 2017 letter to the same court, Badri Daher, the new head of the customs department, repeats the same plea.

In this communique, seen by The Independent, he writes that it follows similar letters sent in 2014, 2015, twice in 2016 and earlier in 2017. Shortly before his arrest, Daher, who is among more than a dozen port officials currently under investigation, said he received no proper instructions of what to do.

In December 2019, the State Security requested an investigation into dangerous substances in Hangar 12 and completed its findings in January. It informed the presidency and the prime minister a few months later.

President Michel Aoun admitted that nearly three weeks before the blast – on 20 June – he was handed that report and informed that the dangerous material had been there for seven years.

He said he immediately ordered the military and security officials “to do what is needed”.

Prime Minister Hassan Diab, whose government resigned on Monday, received the same letter on the same day and sent it on to the Supreme Defence Council for advice within 48 hours.

But still nothing was done.

The matter was even raised just 11 days before the blast when the public works minister, Michel Najjar, told Al Jazeera he first learnt about the dangerous stockpile.

Because of a new coronavirus lockdown in place at the time, Najjar said there was a short delay and so he spoke to the port’s general manager, Hassan Koraytem, about the matter on the Monday 24 hours before the blast.

The port manager said he would send all the relevant documentation so everyone could look into the matter. But it was too late.

Thirteen minutes that sealed the city’s fate

On the afternoon of Tuesday 4 August, port electrician Joe Akiki, 23, called his mother to say he was starting the night shift.

Most of the port workers clock off at 4pm each day. And so there were comparatively few people on the ground when, a few hours later, a fire started.

Shortly before 6pm local time, Akiki stood on the roof of a building which was part of Beirut’s imposing grain silo. He started filming black smoke billowing out of warehouse 12, which was about 40m away in front of him.

In the clip, the camera pans across left to right across the battered hangar. Faint sirens, perhaps belonging to the incoming fire crew, can be heard sounding in the background.

Joe Akiki films the burning warehouse from on top of the silo minutes before the blast

Around the same time, at 5:55pm, a member of the fire department operations room just east of the port received a call from the Beirut police department saying there was a fire in one of the warehouses.

Fires at the port are not uncommon, he told The Independent. But the way it was reported and handled was unusual. The fire department employee who received the call said no one mentioned ammonium nitrate or explained to them which hangar was affected.

A 10-person team – nine male firefighters and female paramedic – was dispatched to the scene arriving just two minutes later.

There, unusually, there was no port crew to greet them, show them the site and hand them the key. It took them some time to work out the location of the fire.

Fire department officials told The Independent had they known the contents of the warehouse and its location or even been given a key, they would have had more time to assess the danger and the contents of the hanger, possibly put out the initial fire, order an evacuation or just scramble to safety.

Instead the firefighters wasted precious minutes that could have saved lives – their lives – trying to locate and break into the warehouse.

“Each minute counts in our work. If they just had more information,” said fire department chief Fadi Mazboudi.

At some point an unknown person, likely a port worker, began filming from the exact same spot where Akiki was standing. The clip that was shared online and verified by Bellingcat shows the smoke thickening to a deep charcoal. The crackle of dozens of what appear to be fireworks can be heard, popping in time with bright white and red sparks.

The person filming begins to retreat from the fire as it grows. A man screams as a large explosion sends them scrambling across the roof.

Across town, just before 6pm, that initial blast was heard by many residents who took to social media to tweet pictures of the column of smoke towering in the sky.

As the minutes trickled by more people came out of their homes, businesses, and shops, or looked out their window to find out what was going on.

Just 600m south of Hangar 12, Cherine el-Zein, an interior designer and activist, started filming the cloud above the port and telling people they should shut the doors and windows because of the smoke.

Cherine el-Zein films the moment the explosion destroys swathes of Beirut

A few minutes along Armenia Street to her right, Carmen Khoury, 46, a university administrator, stopped buying water and stepped out of the shop with a woman she did not know to look for fighter jets.

Back at Hanger 12, Sahar Fares, 27, the female medic accompanying the all-male fire crew had herself already started filming.

From the footage – broadcast by the BBC and verified by The Independent – it is possible to geolocate her to an area just below where Akiki was standing on top of the grain silo.

Her video shows the warehouse on fire, with her colleagues in uniform looking up at the burning building. She sent this clip to her fiance Gilbert Karaan at 6.03pm, according to Mazboudi. Worried, Gilbert spoke to her on the phone, urging her leave. He was still on the call when, disoriented, she started to run towards the grain silo.

A minute later at 6.04pm, Akiki, presumably scared and confused, sent his three-second clip with no explanation to a WhatsApp group chat: the last time his friends would ever hear from him.

By this point the firefighters realised the enormity of the situation that they had walked into blind. The fire was much bigger than they anticipated.

And so a few seconds before 6.08pm, firefighters Elia Khizami and Charbel Karam called their superiors demanding immediate back-up. They warned they only had “three tons of water” which wasn’t enough to control such a massive fire.

But before anyone within the fire department could scramble together a single piece of equipment, Hangar 12 detonated.

Fares was still on the phone to her fiance and running for safety when the line cut.

The sky above her imploded into a brilliant and billowing roar of orange and deep red, which set off a white ring of pressure consuming everything in its path.

The fire department employee who took the original phone call is thrown metres in the air in his office, which is ripped open.

For Carmen Khoury, just a few hundred metres away from the epicentre, it felt like hell had been unleashed.

“An iron rod swung down and knocked me off my feet. I found myself pinned under a car, with the woman beside me bleeding,” she says, describing the horrific moment.

“I have lived through two wars, and I have never experienced a blast quite like that. For a second I thought the world had come to an end.”

The city torn in two

For nearly one whole minute everything on Armenia street was quiet – in a kind of sharp inhalation of breath before the surge of pain.

Cherine el-Zein’s video capturing the moment is black; the only sounds heard are the hiss of gas and the persistent bleat of car alarms.

Then as people regain consciousness the screams start. The sirens begin.

“What just happened? My daughter is inside the shop, my daughter is inside the shop,” shouts one man in desperation. In the distance a woman says something incomprehensible and quietly whimpers.

Across Beirut, blood-soaked bodies staggered through the dust and smoke and glass and mess. Many asked themselves if a war had started.

View from the ocean of Beirut’s devastated port after warehouse explosion

Hala Okeili, who was approaching Armenia street in her car, says everything was instantly destroyed.

“Our neighbours, faces I recognised. Young people bleeding from every single part of their bodies.”

Citizens started making frantic phone calls to family members across the city. People report experiencing hour-long lapses in memory.

Medical workers at the nearest hospital St George, which was gutted by the blast, were forced to pull their own colleagues and patients from under the fallen masonry. With the emergency room destroyed, the generator broken and parts of the building structurally unsound, they started treating the newly injured in the car park with the light of their mobile phones.

Citizens on motorcycles began to ferry the shell-shocked injured, many hastily patched up by well-wishers, to hospitals outside the city, as those close to downtown Beirut were each capacity.

At the port, the explosion had clawed a 43m-deep crater, overturned cruise ships like beached whales, destroyed half of Lebanon’s main grain silo, and left just the rickety ribs of the warehouses.

Days later, rescue workers issued diminishing percentages of the likelihood of finding survivors there. Angry families gathered at the site demanding bulldozers check under the warehouses in case anyone made it an underground network of tunnels and store rooms.

In succession the bodies of Fares, Akiki and Khizami are found within the rubble, many of them incinerated and in pieces. But the rest of the team, including Karam, remain missing.

‘Hang up the nooses’

Very quickly in the aftermath of the blast, the shattered streets of Beirut begin to simmer with rage. Protesters armed with nooses demand accountability and help from their government whose officials are woefully absent in the rescue and clean-up operation manned by volunteers.

Among the crowds are Khoury and El-Zein, who protest despite having been hospitalised. The unidentified woman pinned under the car with Khoury doesn’t make it.

A nation’s grief turns to fury.

“There’s not one form of death they haven’t used with us,” says Sara Assaf, a Lebanese activist at one rally. She says this was no accident, but the result of years of endemic corruption at every level of public life by the country’s leaders.

“They killed us financially. They killed us economically. They killed us physically. They killed us morally. They killed us chemically.”

Since the explosion, everyone has passed the buck. President Aoun insisted on Friday he is not responsible, saying that he didn’t know where the ammonium nitrate was placed or “the level of danger”.

Watch more

Lebanon president admits knowing about explosive stockpile weeks ago

Port officials, before their arrests, had expressed similar sentiments, saying they warned the courts, which did nothing. Najjar told Al-Jazeera “no minister knows what’s in the hangars or containers, and it’s not my job to know”.

Hassan Diab, in his resignation speech on Monday, blamed the political elite and his predecessors for hiding the problem for seven years.

The obvious question is why nothing at any point was practically done.

Many have even questioned the little action that was taken: the letters written by the port officials.

One document shown to The Independent – dated June 2014 before the shipment was even unloaded – apparently shows an Urgent Matters Court judge telling port officials that his court did not have the jurisdiction to authorise the sale of the ship or its contents.

Beirut protesters stormed government buildings (EPA)

Investigative journalist Riad Kobeissi says this proves that all the subsequent letters were completely pointless, since the court could not authorise what the customs officials were ultimately asking: to resell or reimport the stockpile of ammonium nitrate.

“Why keep writing the same letter over and over again? Why didn’t they go immediately to the security forces or higher up and press for action all those years ago?” he asks.

The Independent spoke to port officials but they declined to speak on this. The prime minister’s office did not reply to a request for comment.

The security forces manning the rescue effort directed The Independent to the confidential investigation team that is not speaking to the media. The merry-go-round continues.

And while the authorities continue to finger-point and deflect blame, more bodies are unearthed – many of them the first responders.

“I am numb, a lost ship, I have been unable to cry,” says a fellow firefighter describing how he lost 10 of his best friends by that hangar on Tuesday. A team he calls his family.

“They are national heroes and were sent to their certain deaths. We have lost everything. We will make them pay.”

Port officials, before their arrests, had expressed similar sentiments, saying they warned the courts, which did nothing. Najjar told Al-Jazeera “no minister knows what’s in the hangars or containers, and it’s not my job to know”.

Hassan Diab, in his resignation speech on Monday, blamed the political elite and his predecessors for hiding the problem for seven years.

The obvious question is why nothing at any point was practically done.

Many have even questioned the little action that was taken: the letters written by the port officials.

One document shown to The Independent – dated June 2014 before the shipment was even unloaded – apparently shows an Urgent Matters Court judge telling port officials that his court did not have the jurisdiction to authorise the sale of the ship or its contents.

Beirut protesters stormed government buildings (EPA)

Investigative journalist Riad Kobeissi says this proves that all the subsequent letters were completely pointless, since the court could not authorise what the customs officials were ultimately asking: to resell or reimport the stockpile of ammonium nitrate.

“Why keep writing the same letter over and over again? Why didn’t they go immediately to the security forces or higher up and press for action all those years ago?” he asks.

The Independent spoke to port officials but they declined to speak on this. The prime minister’s office did not reply to a request for comment.

The security forces manning the rescue effort directed The Independent to the confidential investigation team that is not speaking to the media. The merry-go-round continues.

And while the authorities continue to finger-point and deflect blame, more bodies are unearthed – many of them the first responders.

“I am numb, a lost ship, I have been unable to cry,” says a fellow firefighter describing how he lost 10 of his best friends by that hangar on Tuesday. A team he calls his family.

“They are national heroes and were sent to their certain deaths. We have lost everything. We will make them pay.”

No comments:

Post a Comment