It’s possible that I shall make an ass of myself. But in that case one can always get out of it with a little dialectic. I have, of course, so worded my proposition as to be right either way (K.Marx, Letter to F.Engels on the Indian Mutiny)

Sunday, August 28, 2022

August 26, 2022

Dr. Hans-Jakob Schindler and Riza Kumar

Following two days of indirect peace talks hosted by the Afghan Taliban in Kabul in early June, Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP)—an umbrella group of more than a dozen distinct Pakistani Taliban factions first formed in 2007—declared an indefinite extension of a ceasefire with the Pakistani government. The ceasefire extension, the second in two months, is reportedly the longest in the terror group’s history.

However, the ceasefire has not been strictly observed. According to the Pakistan Institute for Conflict and Security Studies, TTP militants reportedly carried out 33 attacks which killed 34 people and injured 46 others in July, an increase of seven attacks compared to June. Islamabad, for its part, has been accused of continuing to target the TTP. In April, Pakistani war planes carried out a strike on the TPP in Afghanistan. On August 8, a roadside bomb exploded in Afghanistan’s eastern Paktika province, killing senior TTP leader Omar Khalid Khorasani and other senior militants Mufti Hassan Swati and Hafiz Dawlat Khan. The TTP claimed Pakistani intelligence agents were responsible for the attack.

The TTP and Islamabad have previously engaged in peace negotiations to no avail and the Taliban’s role in this process has not made the prospect of a long-term peace agreement much more promising. The Taliban have provided the TTP with a safe haven since coming to power one year ago and the TTP has been vocal in its allegiance to and admiration of the regime’s approach to governing. Following the Taliban’s takeover of Kabul, the TTP was emboldened to violently reassert influence across Pakistan and the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) that border Afghanistan. Additionally, senior Afghanistan Taliban cabinet members—particularly Minister of the Interior and Haqqani Network leader, Sirajuddin Haqqani—have demonstrated support for the TTP, insisting that Pakistan address the group’s “grievances.” This close connection was confirmed when the Haqqani Network acted as a mediator between the government of Pakistan and the TTP in earlier negotiations in 2021, as well as in the current talks.

In this ongoing round, the TTP has asked for Pakistani government forces to pull out of former tribal regions of the northwestern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, the release of TTP fighters in government custody, and the revocation of all legal cases against the terror group. The Pakistan government wants the TTP to eventually disband and to sever its ties with ISIS in both Pakistan and Afghanistan. In terms of the latter condition, the Taliban would significantly benefit from weakened ties between the TTP and ISIS given the terror group’s continued threat to Kabul.

In May 2022, the U.N. published a report stating that the TTP constitutes the largest component of foreign terrorist fighters in Afghanistan, with troops numbering approximately several thousand. Additionally, the Taliban and the TTP maintain deep historical and ethnic connections and strong affiliations with al-Qaeda. Although Pakistan provided the Taliban with decades of support during its years of struggle against the U.S. and Afghan government, since returning to power, the Taliban has frustrated their former benefactors and may now be reassessing their ambitions in the region.

Immediately upon returning to power in Afghanistan, the Taliban released 780 TTP prisoners, including the former deputy head, Molvi Faqir Muhammad. The released prisoners significantly boosted the TTP’s troop size but also provided the Taliban with scores of militarily skilled supporters. Given the increased number of high-casualty attacks by ISIS-K throughout Afghanistan, it is fair to presume the Taliban is incentivized to maintain TTP loyalty. The Afghan Taliban stands to benefit from any scenario that prevents the strengthening of ISIS-K, which has challenged the Taliban’s ability to govern and has severely compromised Afghanistan’s national security. However, the prospect of an actual peace agreement could potentially backfire, as some hardline TTP members might defect to ISIS-K. In fact, from the onset ISIS-K welcomed a significant number of former TTP fighters.

Aside from security concerns, the Taliban’s role as mediator may also be impacted by dire economic and environmental circumstances—as well as international skepticism of the regime’s credibility—which continue to plague Afghanistan. Afghanistan is facing severe economic struggles and drought, causing almost 23 million of its people to become dependent on humanitarian aid. If the Taliban can facilitate peace between enemies within the region, they may soften their international reputation and persuade the U.S. as well as other states and donors to unfreeze Afghan funds.

While the Taliban has taken on the role of a mediator in the peace talks, it is uncertain if the Taliban has been anything but self-serving in this process. Although it is unreasonable to assume TTP attacks will immediately cease following another peace agreement, given that various factions within the TTP see a ceasefire critically, it is critical to consider whether the Taliban will ever hold the TTP accountable for their continued violence. The TTP recently stated that it seeks real peace in Pakistan, and that it is neither anti-state nor working for anti-Pakistan powers. However, it is uncertain to what extent the group will cooperate with Islamabad when their ultimate goal is to replace the elected government of Pakistan with an emirate based on their interpretation of sharia. The first peace agreement between the TPP and the Pakistani government signed in May 2004 necessitated a ceasefire that only lasted 50 days, and others in 2006 and 2008 also failed to end ongoing extremist violence.

The Taliban’s unwillingness to crack down on the TTP demonstrates why their role as a negotiating partner is concerning for U.S. anti-terrorism efforts in the region and beyond. The Pakistani government, distracted by an internal political and economic crisis and a growing insurgency in its southern Baluchistan province, fueled by U.S. manufactured weapons flowing out of Afghanistan, may see current negotiations as it best short-term option, albeit not a long-term solution. Although few details of the negotiations have emerged, one thing is certain, the implications of the Taliban’s actions will extend far beyond South Asian regional security.

Tuesday, February 21, 2023

Traders troubled after Taliban shut Afghan-Pakistan crossing

A Pakistani paramilitary soldier, left, and Taliban fighters stand guard on their respective sides, at a border crossing point between Pakistan and Afghanistan, in Torkham, in Khyber district, Pakistan, on Sept. 5, 2021. The main crossing on the Afghan-Pakistan border remained shut Tuesday, Feb. 21, 2023, for the third straight day, officials said, after Afghanistan's Taliban rulers earlier this week closed the key trade route and exchanged fire with Pakistani border guards.

RIAZ KHAN

Tue, February 21, 2023

PESHAWAR, Pakistan (AP) — The main crossing on the Afghan-Pakistan border remained shut Tuesday for the third straight day, officials said, after Afghanistan's Taliban rulers earlier this week closed the key trade route and exchanged fire with Pakistani border guards.

The closure has added to increasing tensions between the two neighboring countries and concerns for traders, for whom the Torkham crossing is a key commercial artery. Trucks carrying various items also travel to Central Asian countries from Pakistan, through Torkham crossing point and Afghanistan.

On the Pakistani side of the border, in northwestern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, many merchants watched their trucks on Tuesday, loaded with fresh produce that could soon spoil, and waited for the crossing to reopen.

The Taliban closed Torkham on Sunday, angered by Pakistan’s alleged refusal to allow Afghan patients and their caretakers to enter Pakistan for medical care without travel documents. On Monday, Taliban fighters and Pakistani guards exchanged fire. There was no word on casualties on either side.

According to Ziaul Haq Sarhadi, a director at the Pakistan-Afghanistan joint Chamber of Commerce and Industry, nearly 7,00 trucks carrying various goods — including perishable fruit and vegetables — were stuck and lined up, waiting at the Pakistani side.

Hundreds of Pakistanis with valid travel documents were also waiting near Torkham for the crossing to reopen, he added. “It is causing problems for traders on both sides.”

There were also vehicles waiting on the other side of the border, in Afghanistan's eastern Nangarhar province, but the Taliban have not commented on the issue.

Siddiqullah Quraishi, the Taliban’s appointed official at the Nangahar’s information and culture department, said Pakistan has not been abiding by its “commitments, so the crossing point was shut down.” He did not elaborate but advised Afghans to avoid traveling to the crossing until further notice.

Closures, cross-border fire and shootouts are common along the Afghan-Pakistan border. Each side has in the past closed Torkham, and also the Chaman crossing in southwestern Pakistan, over various reasons.

The Taliban seized power in Afghanistan in August 2021 as U.S. and NATO troops were withdrawing from the country after 20 years of war. Like the rest of the world, Pakistan has so far not recognized Afghanistan’s Taliban government. The international community has been wary of the Taliban’s harsh measures, imposed since their takeover, especially in restricting the rights of women and minorities.

___

Associated Press writer Rahim Faiez in Islamabad contributed to this story.

Wednesday, November 08, 2023

Pakistan says most Afghans have left voluntarily, a claim rejected by Kabul which calls the Pakistani action ‘unilateral’ and ‘humiliating’.

By Abid Hussain

Published On 7 Nov 2023

Islamabad, Pakistan – Pakistan’s decision to expel more than 1.5 million allegedly undocumented Afghan refugees and migrants has once again triggered tensions with the Taliban-ruled Afghanistan.

Since October 31 when a government deadline for the refugees to leave Pakistan or face detention ended, more than 200,000 Afghans have crossed into Afghanistan, officials said, amid stringent criticism by Kabul.

“This is injustice, an injustice that cannot be ignored in any way. The forced expulsion of people is in conflict with all the norms of good neighbourliness,” Bilal Karimi, spokesperson for the Afghan government, told Al Jazeera on Monday.

“In the long term, there may be many negative effects on the relations and communications between the two countries.”

Pakistan says most Afghans have left voluntarily, a claim rejected by Kabul which has called the Pakistani action “unilateral” and “humiliating”.

“The expulsion of Afghan refugees in such a large volume and in such a humiliating manner, when winter is coming and the weather is getting colder, is a cruel and unfair decision,” Karimi said.

In the late 1970s and 1980s, tens of thousands of Afghans fled to Pakistan after the Soviet invasion of the country, and more came after the United States attacked the impoverished country following the 9/11 attacks.

More recently, between 600,000 and 800,000 Afghans are believed to have arrived in Pakistan after the Taliban assumed power in 2021.

According to the Pakistani government, there were about 4 million foreigners in the country before October 31, nearly 3.8 million of them Afghans. Of those, it says, only 2.2 million Afghans carry a government-approved document that makes them eligible to stay.

Islamabad blames the Afghan fighters and migrants for a surge in armed attacks inside Pakistan in recent years.

On October 3 when the decision to deport “illegal” refugees was announced, interim Interior Minister Sarfraz Bugti said of the 24 suicide bombings in the country this year, 14 were carried out by Afghan nationals.

At the centre of the deteriorating relations between the neighbouring nations is Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), a banned armed group also referred to as the Pakistani Taliban for its ideological proximity to the Taliban rulers in Afghanistan.

Founded in 2007, the TTP says its goal is to impose its hardline interpretation of Islamic law over Pakistan.

The group has been accused of hundreds of deadly attacks after it ended a ceasefire agreement with the Pakistani government a year ago. On Saturday, it allegedly attacked a Pakistan Air Force base in Mianwali in Punjab province, damaging three grounded aircraft.

But most TTP attacks have mostly taken place in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan provinces, both of which share a long border with Afghanistan.

Pakistan says the TTP enjoys safe havens in Afghanistan and uses its soil to launch attacks against Pakistani security forces and installations. Afghan authorities have consistently denied the allegations, saying they have nothing to do with Pakistan’s internal security concerns.

Last week, Afghanistan’s interim Prime Minister Mullah Mohammad Hassan Akhund said Pakistan’s decision to expel refugees violated international laws. “You [Pakistan] are a neighbour, you should think about the future,” he said.

Akhund’s deputy Sher Mohammad Abbas Stanikzai was more scathing in his response, warning Islamabad to “not force their hand to react over the move”.

“We expect Pakistan’s security forces and civilian government to change their behaviour. The reaction of Afghans is historically known to the whole world. Most of the time they don’t show any reaction, but if they do show, they are recorded in history,” Stanikzai said during a news conference in Kabul on Monday.

Analysts, meanwhile, believe Pakistan has been unable to control the TTP attacks and instead decided to expel Afghans as a “frustrated” response aimed at forcing Kabul to act against the armed group.

“Pakistan’s negotiations with the Afghan Taliban have failed repeatedly and this frustration is two years in the making. Now, seeing they don’t have any leverage over Afghan Taliban, they are using the refugee expulsion as a pressure tactic,” Abdul Basit, research fellow at S Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore, told Al Jazeera.

Basit said the move to deport Afghan refugees was “ethically and morally wrong” and amounted to xenophobia. “This move is counterproductive and will only create more problems than solving the existing ones,” he said.

But Islamabad-based security analyst and former army officer, Muhammed Zeeshan, disagrees, saying armed groups such as the TTP require refuge and logistics, and the Afghans, many of whom live in the suburbs of major cities, became “exploitable havens” for the attackers.

“I believe the time has come to deal with Afghanistan’s interim government firmly, if not strictly. We need to step out of the concept of brotherhood. It’s not about that anymore, but about survival of Pakistan, and peace and security here,” he told Al Jazeera.

Journalist Sami Yousafzai says Pakistan’s deportation policy is a sign of desperation since it is unable to find common ground with Kabul over the TTP.

“Afghan citizens always viewed Pakistan with scepticism and with a negative lens. With this policy of deporting Afghans, this perception is only going to get reinforced,” he told Al Jazeera.

Analyst Basit said the forced return of refugees back to Afghanistan has perhaps pushed them to their “worst nightmare: to live under the Taliban rule”.

“These people ran away from them after August 2021, and now we are sending them back forcibly. Afghan people have lived through 40 years of wars and instability, and now they are being forced back, all because of Pakistan’s frustration with the interim rulers of Afghanistan,” he said.

“This war [against TTP] has either villains or victims, and Afghan refugees are the victims in this story.”

SOURCE: AL JAZEERA

Monday, January 22, 2007

Skool Daze

KANDAHAR, Afghanistan (AP) - The Taliban said it will open its own schools in areas of southern Afghanistan under its control, an apparent effort to win support among local residents and undermine the western-backed government's efforts to expand education.

| Afghan girls received school bags during the inauguration of a village primary school, built by Canadians, in Sparwan Ghar, 38 kilometres west of Kandahar, Afghanistan, on Saturday. |

Of course it would help a lot if Pakistan's Military Intelligence Agencies were not funding and supporting the Taliban.

Of course it would help a lot if Pakistan's Military Intelligence Agencies were not funding and supporting the Taliban.Since the Taliban schools are not schools but Madrasa for training insurgent fighters.

Afghan education minister says Taliban plan to set up schools is 'political propaganda'Atmar described the Taliban as "enemies" of education, saying its militants had burned 183 schools in the past year, caused the closure of 396 others, forcing 200,000 students out of class. He also said 61 students and teachers had been killed.

"If they want to build schools, why are they burning our (government) schools?" he said.

Atmar dismissed the Taliban plan to open its own as "political propaganda," saying they did not control the provinces where it plans to set them up.

He said the government would have the "legitimate right" to attack Taliban schools that became centers of terrorism.

The Taliban's attacks on state schools in the past few years have chipped away at one of the main successes of Afghanistan's democratic revival: a huge foreign-funded development drive that has seen a fivefold increase in the number of children attending school.

Quetta is now the headquarters of the Taliban movement. What role are Pakistan’s intelligence agencies playing to sustain their presence?

President Musharraf relies on the religious party Jamiat Ulema-i-Islam, or JUI, which dominates this province, Baluchistan, as an important partner in the provincial and national parliaments.

At a madrasa, called simply Jamiya Islamiya, on winding Hajji Ghabi Road, a board in the courtyard proudly declares “Long Live Mullah Omar,” in praise of the Taliban leader, and “Long Live Fazlur Rehman,” the leader of JUI.

Members of the provincial government and Jamiat Ulema-i-Islam are frequent visitors to the school, the local opposition party member said, asking that his name not be used because he feared Pakistan’s intelligence services. People on motorbikes with green government license plates visit at night, he said, as do luxurious sport utility vehicles with blackened windows, a favourite of Taliban commanders.

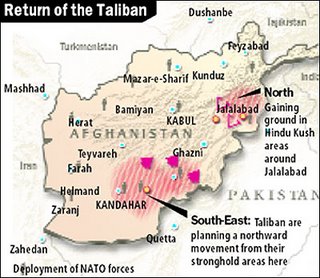

Increasing Pakistani role seen in Taliban resurgence

The all-powerful Inter Services Intelligence (ISI), which had for long "used religious parties for Pakistan's domestic and foreign policy adventures", is extensively providing support to the Taliban.Western diplomats in Pakistan as well as Afghanistan say the ISI and the Military Intelligence are actively supporting a Taliban restoration in an effort to assert greater influence on the country's "vulnerable western flank" (read the porous Pak-Afghan border regions).

According to the New York Times, this is motivated not only by an Islamic fervour but also by a longstanding view that the jihadist movement allows them to assert greater influence in Afghanistan's border region.

According to the paper, so great is the ISI influence that even families who have lost their sons in suicide bombing missions against American and NATO forces in Afghanistan, say of the deaths on conditions of anonymity because of pressure from Pakistani intelligence agents.

The paper quoted a former Taliban commander as saying that Pakistani authorities jailed him when he refused to go to Afghanistan to fight against the NATO and Afghan forces, adding that for Western and local consumption, his arrest was billed as part of Pakistan's crackdown on the Taliban in the country.

According to Pakistani and Afghan tribal elders, former Taliban members who have refused to fight in Afghanistan have been arrested, or even mysteriously killed, after resisting pressure to re-enlist in the Taliban.

"The Pakistanis are actively supporting the Taliban," said a Western diplomat in Kabul, adding that he had seen an intelligence dossier highlighting a recent meeting on the Afghan border region between a senior Taliban commander and a retired colonel of the ISI.

Civilians on the border fear ISI

Carlotta Gall, a New York Times correspondent, who was manhandled and punched on December 19 by Pakistani agents who broke into her hotel room in Quetta, said Pakistanis and Afghans interviewed on the frontier — frightened by the long reach of Pakistan's intelligence agencies, spoke only with assurances that they would not be named. Even then, they spoke cautiously.

Despite this, they were visited by the ISI because the goons who broke into her hotel room copied data from the computers, notebooks and cellphones they seized, and tracked down her contacts and acquaintances.

They have been lucky not to have been killed so far because the ISI has a built a hideous reputation for bumping off people they see as being inimical to hardline Pakistani interests.

Some months back, Hayatullah Khan, a Pakistani journalist who exposed as lie the Pakistan military's claim of an attack on a terror camp (which was actually conducted by the US) was killed in cold blood.

See:

Our Allies In Afghanistan Oppress Women

Womens Oppression Continues In Afghanistan

Find blog posts, photos, events and more off-site about:

Afghanistan, War, Harper, Conservatives, Liberals, Canada, politics, military, NATO, peacekeeping, Karzai, Afghanistan, Men, misogyny, women, feminism, RAWA, Northern Alliance, Taliban, Kabul, Karzai, Islam, girls, school,

Musharaff, Pakistan, ISI, intelligence, counter-intelligence, spying, Mujahedin, Al-Quaeda, Bin-Laden, terrorism, India, terrorists, Taliban,

Monday, August 30, 2021

Attacks on religious minority prompt exodus of thousands across border to Pakistan to seek safety

Shah Meer Baloch in Chaman

Sun 29 Aug 2021

As word of Kabul’s fall to the Taliban spread across Afghanistan, there were few who greeted the news with as much fear as the Hazara Shias. The religious minority in this Sunni majority country were among the most persecuted groups when the Taliban last ruled Afghanistan, and the memories of the killings, torture and mass executions have not faded.

Signs point to Hazaras once again finding themselves a target of the Taliban. A recent Amnesty report found that Taliban militants were responsible for the murder of nine Hazaras in July, in the village of Mundarakht. Six of the men were shot and three were tortured to death, including one man who was strangled with his own scarf and had his arm muscles sliced off.

Attacks such as these have prompted a mass exodus of Hazara people over the border to Pakistan, and activists say that about 10,000 have arrived in the Pakistan city of Quetta, in Balochistan, where they are living in mosques and wedding halls, and renting rooms. Several Hazaras told the Guardian they had paid traffickers from £50 to £350 to get them across the border.

Among those sheltering in Quetta was Sher Ali, 24, a shopkeeper, who had escaped with his wife and baby. Ali reached Chaman on the Pakistan side of the frontier on Thursday. The journey, through territory controlled by the Taliban, had taken three days. They had driven along roads decimated by bomb blasts, passing burnt-out cars and destroyed bridges.

Ali had decided to leave after he witnessed his friend Mohammad Hussain, 23, being shot dead by the Taliban 10 days ago in Kabul. Hussain had been passing through a Taliban security checkpoint on a motorbike. He refused to stop and they fired at him with an assault rifle.

“When I went to the spot, Hussain’s dead body was lying on the road in a pool of blood. They emptied the AK-47 on him,” said Ali. “It was the moment I decided to leave. It is like a do or die situation for Hazara Shia; whether to leave and live, or stay and die.”

In recent days, there have been chaotic scenes at the Chaman border crossing, as tens of thousands of Afghans have attempted to make it across. Only those with Pakistan residency papers or people travelling to Pakistan for medical treatment are officially allowed in, but some of the Hazaras said traffickers would bribe authorities at the border to get Afghans across illegally.

‘Everyone is afraid’: Afghans fleeing Taliban push for exit into Pakistan

Ali said his remaining family members would be leaving for Pakistan within a few days. “We can’t live in the Taliban’s Afghanistan,” he said.

Mohammed Sharif Tahmasi, 21, a computer science student from Ghazni province, reached Chaman along with his two sisters and brother on Thursday. After making the border crossing, they waited in a muddy corner near the border fence for some more Hazara families so they could travel to Quetta together.

Tahmasi’s family has never been to Pakistan but his parents had given the children some money and instructed them to urgently get over the border as soon as they could.

“All Hazara parents are asking their children to leave Afghanistan and be safe,” said Tahmasi. “I don’t know how my parents and the other siblings are, but I hope my siblings are fine and they will cross soon.”

Sharif’s sister Nahid Tahmasi, 15, a student in an elementary school, said she did not want to abandon her parents but, before she had left Ghazni, Taliban restrictions on women had already begun to be enforced.

“I feel terrible,” she said. “I can’t go to school and I miss my city and friends. I miss my parents. I miss my school. When the Taliban took control of Ghazni province they banned girls’ entry into public parks and schools. They did not want girls to study. We could not roam outside, visit our neighbours and dress the way we want.”

Gulalai Haideri, a Hazara who worked as a teacher at the Women for Afghan Women NGO, in Faryab province, reached Quetta five days ago. She is pregnant and sold her jewellery to pay for the journey and to be smuggled across the border.

“We were rejected twice for entry but then I begged the guards to allow me to enter as I am pregnant and I can’t live in Afghanistan. I am a woman, I will be killed,” she said. “They had mercy and allowed my family to enter.”

Haideri said that after her province fell to the insurgents, the Taliban had been going door to door to find unmarried girls, orphaned girls, divorced women and widows to get married to their fighters.

Mohammad Fahim Arvin, 21, a student at the Kabul Polytechnic University, was told by his parents to leave and save his life. But he spoke of his sadness at having to leave his parents behind.

“The Taliban hate us and want us to join them and fight for them, but we can’t,” said Arvin. “It is not my fault I was born as a Hazara; it was God’s decision. It was not in my hands. Why do they [Taliban] want to kill us for being Hazara?”

Yet even in Pakistan, the Hazaras are not in safe territory. Here too they have been persecuted for three decades by the Sunni militant groups. Earlier this year, 10 Hazara miners working in Balochistan were murdered by members of Islamic State. According to a 2019 report by Pakistan’s National Commission for Human Rights, at least 509 Hazara have been murdered for their faith since 2013.

For many of Afghanistan’s Hazara community arriving into Pakistan with little money and no connections, they have had to rely on the kindness of the local community.

Syed Nadir was among those hosting five Hazara families, including Haideri’s family in Quetta who had arrived in recent days.

“I don’t know any of them, but all Hazara are going through one of the worst times,” he said. “They are leaving their homes and we should host them. All countries should play their part for the Hazaras and the Afghans.”

Wednesday, September 15, 2021

Perturbed over Pakistan, Qatar and Turkey's outreach to Taliban, Saudi Arabia eyes closer ties to India

Saudi Prince, Faisal bin Farhan Al Saud is expected to be in New Delhi this weekend as part of his first visit to India as foreign minister where talks will mostly focus on the evolving situation in Afghanistan

Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Saudi Arabia's Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman in Riyadh. AFP

Saudi Arabia foreign minister Prince Faisal bin Farhan Al Saud is expected to visit India this weekend to discuss the unfolding situation in Afghanistan and the Taliban’s takeover of the country.

Prince Faisal, scheduled to land in India on 19 September, is expected to hold meetings with External Affairs Minister Dr S Jaishankar, National Security Advisor (NSA) Ajit Doval and also Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

This meet comes after Prime Minister Narendra Modi discussed the Afghanistan situation with UAE crown prince Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan on 3 September over the telephone, External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar hosted Dr Anwar Gargash, diplomatic advisor to UAE president, on 30 August and exchanged notes on the Kabul crisis.

Qatar, Turkey’s and Pakistan’s proximity to Taliban

India's allies in West Asia, Saudi Arabia and the UAE, are worried about the security ramifications of a Taliban-led Afghanistan and the ties shared by the Taliban and global terrorist networks.

The two nations are also said to have been perturbed by the active role played by Qatar, Turkey and Pakistan in engaging with the Taliban regime.

Qatar has turned out to be a trusted mediator in this conflict.

Doha has become a key broker in Afghanistan following last month's withdrawal of US forces, helping evacuate thousands of foreigners and Afghans, engaging the new Taliban rulers and supporting operations at Kabul airport.

Since the US pullout, Qatar Airways planes have made several trips to Kabul, flying in aid and Doha's representatives and ferrying out foreign passport holders.

Meanwhile, Turkey, which has strong historical and ethnic ties in Afghanistan, has been on the ground with non-combat troops as the only Muslim-majority member of the NATO alliance there.

According to analysts, it has developed close intelligence ties with some Taliban-linked militia. Turkey is also an ally of neighbouring Pakistan, from whose religious seminaries the Taliban first emerged.

Last week, it was reported that Turkish officials held talks with the Taliban lasting over three hours. Some of the discussions were about the future operation of the airport itself, which Turkish troops have guarded for six years.

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has also stated: "Turkey is ready to lend all kinds of support for Afghanistan's unity but will follow a very cautious path."

Professor Ahmet Kasim Han, an expert on Afghan relations at Istanbul's Altinbas University, while speaking to BBC said that he believes dealing with the Taliban will provide President Erdogan with an opportunity.

He says Turkey may try to position itself as "guarantor, mediator, facilitator", as a more trusted intermediary than Russia or China, who have kept their embassies open in Kabul.

"Turkey can serve that role," he says.

According to experts, the Taliban takeover in Afghanistan has delivered a strategic victory to Pakistan, establishing a friendly government in Kabul for the first time in nearly 20 years.

Pakistan has backed the Taliban from their earliest days. Islamabad was one of only three countries to recognise the Taliban government in the 1990s and the last to break formal ties with it in 2001.

It also provided safe havens to Taliban leaders and medical facilities for wounded fighters. This assistance helped sustain the Taliban, even as they lost thousands of foot soldiers.

Pakistan last week sent supplies such as cooking oil and medicine to authorities in Kabul, while the country's foreign minister called on the international community to provide assistance without conditions and to unfreeze Afghanistan’s assets.

Additionally, a Pakistan International Airlines plane from Islamabad flew to Kabul on Monday, making it the first flight to land in Afghanistan from neighbouring Pakistan since the chaotic final withdrawal of US troops last month.

Saudi-Taliban ties

In the past, they worked together. But today, Saudi Arabia and the Taliban are separated by political and cultural differences, as well as some problematic history.

The last time the Taliban ran Afghanistan, between 1996 and 2001, Saudi Arabia was one of only three countries in the world to officially recognise the Islamist group's government. Neighbouring Pakistan and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) were the other two.

The situation changed dramatically for Saudi Arabia and the UAE after Al-Qaeda, the Sunni Muslim terrorist group, carried out suicide attacks in the US on 11 September, 2001, resulting in the deaths of over 3,000 people.

This was because Saudi Arabia had a diplomatic relationship with the United States since 1940 and the American were the Kingdom's strongest allies in trade and security.

Experts note that Saudi Arabia's once-close ties will not be revived any time soon.

The Saudi-US alliance remains important, and the country's ongoing cultural changes also play a part in this.

Saudi's controversial crown prince, Mohammed bin Salman, is trying to modernise his country and the idea of a more liberal and open Saudi Arabia doesn't sit well with lending support to Islamist extremists in other countries.

Moreover, Kabir Taneja, a fellow at the India-based think tank Observer Research Foundation, wrote, "To maintain its image as an upcoming investment mecca, Riyadh will have to make sure it does not once again become home to mass migration of fighters flying in and out of the Afghanistan … or become a hub of funding enabling extremist activities."

Where does India come in?

India’s policymakers must look to Saudi Arabia to expand cooperation in anti-terrorism activities and expand dialogue on relations between the two, which will help protect the India's interests related to Afghanistan.

Saudi Arabia also believes that closer ties to India will help re-balance the geopolitics of the region, whereas India believes a good relationship with Saudi will give it a chance to counter a hostile China-Pakistan axis gaining strategic depth across the Khyber.

Inputs from agencies

Saturday, July 17, 2021

RUPERT STONE

As the war in Afghanistan winds down, China looks to make Afghanistan a bigger part of its regional ambitions.

In 2013, Chinese president Xi Jinping inaugurated the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a vast network of infrastructure projects spanning more than 60 countries. But the BRI largely excludes Afghanistan, moving through Central Asia and Pakistan instead.

That may now be changing. China has steadily increased its involvement in Afghanistan in recent years, and a nascent peace process offers some hope that stability might return to the country, bringing with it the possibility of greater trade and investment.

This shift is reflected in a major new report on the BRI’s expansion into Afghanistan by the Organization for Policy Research and Development Studies (DROPS), a Kabul-based think tank.

The 15-month research project has amassed a vast amount of material gleaned from multiple sources, including previously undisclosed government documents and interviews with high-ranking Afghan officials, making it by far the most comprehensive treatment of Afghanistan’s potential role in the BRI to date.

“Looking at the BRI map, it seemed that it was bypassing Afghanistan,” said Mariam Safi, Director of DROPS and one of the report’s co-authors. “So, we wanted to know if there is any thinking in the Afghan government and stakeholders here on the BRI when it comes to Afghanistan’s potential linkage”.

Afghanistan should fit well into the BRI. It has a serious infrastructure deficit, making it an ideal candidate for Chinese investment. It is also the shortest route between Central Asia and South Asia, and between China and the Middle East, while also serving as a gateway to the Arabian Sea.

But China’s role in Afghanistan in the past two decades has been limited. It did not contribute troops to the US-led war that began in 2001, and Beijing has so far refrained from the sorts of big-ticket investments planned for other neighbouring countries, such as Pakistan and Kazakhstan.

But its economic footprint has expanded. China is now Afghanistan’s largest business investor, it has pledged increasing amounts of aid to the country, and Chinese companies have been involved in construction projects.

Beijing has also shown some interest in Afghanistan’s cornucopia of natural resources, which includes vast deposits of essential minerals such as lithium (used in mobile phone batteries).

The country’s weak logistics and security situation make it difficult to extract and transport these resources. But China has got its foot in the door, winning rights to Amu Darya Basin oil in the north and the massive Mes Aynak copper mine near Kabul.

Moreover, Beijing has taken modest steps to include Afghanistan in the BRI. In 2016 Beijing and Kabul signed a Memorandum of Understanding. China has reportedly pledged at least $100 million in funding. However, this is a tiny amount compared to the vast sums proposed for other countries, like Pakistan. And, according to Raffaello Pantucci, director of international security studies at the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), “We still don’t see large projects going forward that quickly on the ground.”

But there has been some progress. In September 2016, for example, the first direct freight train from China reached the Afghan border town of Hairatan. An air corridor linking Kabul and the Chinese city of Urumqi has also been launched under the BRI. Then, in May 2017, Afghan officials attended the massive Belt and Road Forum in China, and in October Afghanistan joined the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, which funds BRI projects.

Kabul has made connectivity a key pillar of its foreign policy, launching various infrastructure projects that could eventually be “brought under the BRI fold,” Mariam Safi tells TRT World.

Reluctant bedfellows

One such initiative is the Five Nations Railway running from China to Iran via Afghanistan, which is still at the feasibility study stage but aligns well with Beijing’s priorities in the Belt and Road. Another is a planned north-south railway corridor that would connect Kunduz with Torkham on the Pakistani border.

Afghanistan has bold plans to expand its almost non-existent railway network. According to internal Afghan government documents reviewed by DROPS, China has pledged “huge support” for these efforts. The north-south railway could facilitate the transport of natural resources while also connecting to Pakistan.

Furthermore, there are various energy projects which could fit well into the Belt and Road vision, such as CASA-1000 and TAP-500 that would export surplus electricity from Central Asia to energy-starved South Asia via Afghanistan, or the TAPI gas pipeline, whose Afghan segment began construction last year (although there is reason to doubt its progress).

Another project that could be included in BRI is the Digital Silk Road fibre optic cable network, funded by China, the US and other partners, which has already connected at least 25 provinces in Afghanistan while aiming to link to China, South and Central Asia, the Middle East, and Europe, according to DROPS.

China has generally eschewed a leadership role in Afghanistan, preferring to work with foreign partners. Some projects, including the Five Nations Railway and Lapis Lazuli Corridor, are jointly financed by China and multilateral lending institutions such as the ADB.

“There has been a lot of cooperative activity on the ground,” Raffaello Pantucci told TRT World, and Beijing seems to view Afghanistan as a place where it can “test out” difficult relationships. China has collaborated with the US there, despite tensions between the two countries, and recently agreed to cooperate with its rival, India.

Sino-Indian efforts in Afghanistan face a hurdle, though, in the form of Beijing’s close relationship with Delhi’s nemesis, Pakistan. 2015 saw the inauguration of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), a vast energy and infrastructure project involving more than $60 billion of potential investment. CPEC was intended to be the Belt and Road’s “flagship” corridor, and, as such, it is already more advanced than other components of the BRI.

According to the report, CPEC is “one of the most feasible options” for integrating Afghanistan into the BRI. There are some cross-border rail and road links at varying stages of development. While none of these is near completion, China clearly wants to move forward.

In 2017 Beijing convened a trilateral dialogue with Pakistan and Afghanistan partly to discuss extending CPEC, but also to ameliorate the rocky relationship between its two neighbours, which has seen border closures and skirmishes. These efforts paid off, as Afghan-Pakistani relations improved in 2018, with a new cooperation agreement in May.

Afghan officials interviewed by DROPS were generally “positive” about CPEC, the report says, but some were wary of excessive dependence on Pakistan. Indeed, as relations with Islamabad soured in recent years, Kabul has diversified its trade away from Pakistan to Iran.

However, the officials were clear “across the board” that Afghanistan still needs Pakistan because it provides the quickest route to the sea, according to Mariam Safi. And, vice versa, Pakistan hopes that Afghanistan may eventually provide access to Central Asian markets.

“At the end of the day there was the realisation that both countries need each other,” Safi told TRT World.

Neither the Afghan nor Pakistani governments responded to requests for comment.

Increasing Chinese footprint

While China’s economic role in Afghanistan has increased, its security presence has grown even more. As the US started withdrawing forces from Afghanistan in 2011, the country became increasingly unstable, raising the risk that insecurity would spill out into Central Asia and Pakistan, potentially disrupting China’s Belt and Road projects there.

Beijing has also been concerned about what they call the threat posed by Uighur and other terrorists using Afghanistan as a base for attacks against the Chinese mainland. In response, China has intensified security on its border, reportedly engaging in joint patrols with Afghan forces and building a base in Badakhshan province, while also launching the Quadrilateral Coordination and Cooperation Mechanism (QCCM) with Afghanistan, Pakistan and Tajikistan.

To counter instability in Afghanistan, China has also stepped up its involvement in peace talks to end the war. Since 2015, it has been involved in a number of multilateral initiatives, including the Quadrilateral Coordination Group and, more recently, the Moscow Format. Beijing has cultivated good ties with the Taliban, meeting them several times in 2018 alone.

Peace may now be on the horizon. The Trump administration has made unprecedented progress in its efforts to negotiate with the Taliban, reaching a provisional agreement in January. The Afghan government still needs to join the talks, however, and there is a long road ahead.

For Beijing, peace would not only reduce the terrorist threat emanating from Afghanistan, but it could also boost Chinese economic activity.

“Afghanistan has been peripheral to the Belt and Road because it simply hasn’t been possible to pursue a serious economic agenda there,” said Andrew Small, a senior transatlantic fellow at the German Marshall Fund of the US and author of The China-Pakistan Axis: Asia's New Geopolitics.

“If there is a political settlement, that could change – though China will still tread very carefully until it’s clear that any settlement holds.”

At the launch of the DROPS report in January, Beijing’s new ambassador to Kabul, Liu Jinsong, said that China was facilitating peace talks to enable Afghanistan’s integration into the BRI, describing the country as a “vital partner” in the initiative.

The appointment of Mr Jinsong, a former director of the Silk Road Fund, “shows that Beijing now considers Afghanistan a priority and wants to include it firmly in its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI),” according to the Berlin-based thinktank, MERICS.

While there is still a long way to go, Beijing is entering a new phase of engagement with its neighbour. “It is certainly true that China is playing a much greater (and higher profile) role in Afghanistan,” said Peter Frankopan, professor of global history at the University of Oxford, whose latest book, The New Silk Roads, examines emerging forms of connectivity in Asia.

“My best guess is that this really is a case of a new page being turned,” Frankopan told TRT World.

The Chinese embassy in Kabul could not be reached for comment. Asked to comment on CPEC’s possible extension to Afghanistan, China’s deputy chief of mission in Islamabad, Zhao Lijian, referred TRT World to a recent interview in which he described Chinese plans to facilitate trade and ease tensions between Afghanistan and Pakistan.

RUPERT STONE

2 AUG 2019

China's first engaged the Taliban to protect its interests in Afghanistan in the 90s. Decades later, history repeats itself.

One is a communist state wary of the threat posed by Islamic extremism, the other a group of religious hardliners with alleged links to Al Qaeda. But, despite their differences, relations between China and the Afghan Taliban go back decades and appear to be strengthening.

Beijing was initially concerned when the Taliban took power in Afghanistan in the mid-1990s. The group had ties to the anti-Chinese terrorist organisation, the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM), which was to allowed to operate camps in the country. China, therefore, happily supported the first round of UN sanctions against the Taliban regime.

But, driven by a mix of security concerns and economic factors, Beijing eventually sought to improve its ties with the movement.

In the late 1990s, China came to believe that the best way to manage the potential terrorist threat from Afghanistan was to engage with the Taliban and strike a deal. Diplomatic relations would also open the potential for trade.

In 1999, Chinese officials broke the ice and flew to Kabul, where they opened economic ties and launched flights between Kabul and Urumqi. China’s ambassador in Pakistan sought a meeting with Mullah Omar. A group of Chinese think tank analysts travelled to Kandahar to make preparations.

According to Abdul Salam Zaeef, former Taliban envoy to Pakistan, the Chinese ambassador was the only foreign diplomat to maintain good relations with their mission in Islamabad at this time. Indeed, Zaeef’s comments about China in his memoir are far less vitriolic than his frequent denunciations of long-time backer Pakistan, which detained Zaeef after 9/11.

The Chinese envoy eventually met Mullah Omar in Kandahar in late 2000. Beijing wanted the Taliban to stop harbouring ethnic Uyghur militants allegedly operating in Afghanistan with ETIM. In return, the Taliban hoped that China would recognise their government and oppose further UN sanctions.

But this deal did not materialise. While Omar did restrain ETIM, he did not expel them. And Beijing did not oppose new UN sanctions against the Taliban; it only abstained.

However, Chinese companies expanded their activities in Afghanistan, and, on September 11, 2001, the two sides signed an MoU to enhance economic ties further.

After 9/11 Beijing gave its backing to Washington’s ‘war on terror’ and supported Hamid Karzai’s new government in Kabul. However, it did not commit troops to the US-led invasion of Afghanistan, and its economic footprint remained small. China was wary of a long-term American military presence in its backyard.

Beijing, therefore, hedged, supporting the Afghan government while maintaining informal contacts with the Taliban. It may have used the Chinese-run Saindak mine in Pakistan for clandestine meetings with the group, according to Andrew Small in The China-Pakistan Axis.

China and Pakistan were the only states to maintain their ties with the Taliban after 9/11.

The group may even have received Chinese weapons, according to Small, and there were also suspicions that the Taliban intentionally avoided attacking Chinese infrastructure projects in Afghanistan. The copper mine at Aynak, near Kabul, had been untouched by the Haqqani Network since China secured extraction rights in 2007.

Hedge your bets

China’s ambivalent foreign policy behaviour in Afghanistan is analogous to its approach in the Middle East, where it also courts opposing sides in regional disputes. As Jonathan Fulton has shown, Beijing has relations with Israel and the Palestinians, and maintains partnerships with Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Iran, a strategy Fulton describes as “fence-sitting”.

For the first decade of the US war in Afghanistan, China’s involvement with the country was minimal. Economic opportunities were dogged by corruption, insecurity and political instability. However, when the Obama administration announced its intention to withdraw US forces by 2014, Beijing grew concerned by the prospect of instability on its border.

The risk of terrorist violence haemorrhaging out of Afghanistan encouraged China to engage more deeply with its neighbour. Chinese diplomats became involved in several multilateral initiatives to seek a political settlement with the Taliban, first at Murree in 2015, then via the Quadrilateral Coordination Group with the US, Pakistan, and Afghanistan.

China was part of the Kabul Process convened by President Ghani in 2017 and sent its diplomats to attend talks with the Taliban and other Afghan politicians in Moscow in 2018. That year President Xi Jinping resuscitated the Afghanistan Contact Group of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), which met again this summer.

There have also been multiple bilateral meetings between Chinese officials and the Taliban in recent years. These discussions were secret and unconfirmed by the Chinese government. But, in June, Beijing publicly announced that it had received a Taliban delegation led by deputy Mullah Baradar (who served eight years in prison in Pakistan before his release in 2018).

China participated in two trilateral events with Russia and the US this year, and in 2017 convened another trilateral forum with long-time foes, Afghanistan and Pakistan, to promote ongoing reconciliation efforts and discuss the possible extension of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) to Afghanistan.

Beijing is concerned that an unstable Afghanistan could provide a safe haven for Uyghur militants, including those currently fighting in Syria. And China is more exposed now due to its massive infrastructure projects in Pakistan and Central Asia, areas especially vulnerable to terrorist spillover from Afghanistan.

Moreover, China’s economic role in Afghanistan has been growing. It is now the country’s biggest foreign investor and appears keen to extend the Belt and Road Initiative there. True, Beijing’s investments in Afghanistan pale in comparison to those in Pakistan, for example, but an end to the war could pave the way for deeper involvement.

A hard bargain

China is well-placed to act as a mediator in Afghanistan. It has decent relations with both sides in the conflict. It is perhaps even better placed to influence the Taliban than Pakistan, which has harassed and detained members of the group since 9/11. Moreover, it has substantial economic incentives to offer.

The Taliban are keen to avoid the isolation they experienced in the 1990s when only three governments (Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE) recognised their regime. Furthermore, they are alert to the need for foreign investment. They have discussed infrastructure with the Uzbek government, for example, and gave their backing to the TAPI gas pipeline project.

But the Taliban’s interest in exploiting the country’s natural resources goes well beyond gas. The group also profits from the mining of Afghanistan’s vast mineral deposits.

“The Taliban has realised that Afghanistan’s mineral wealth offers opportunities to get rich,” writes Peter Frankopan in his new book, The New Silk Roads.

During a trip to Beijing, Taliban delegates were “visibly moved by technology that they told their hosts was inconceivable in Afghanistan because of war,” the New York Times reported. And economic issues were again discussed on the group’s recent visit to China, according to Rahimullah Yusufzai.

Caution is warranted, though. Beijing’s engagement with the Taliban could fail as it did in the 1990s. Then, as now, the group gave assurances that it would not allow terror groups to use Afghan soil for plots against foreign countries. Then, as now, it wanted better trade with the outside world and an end to international isolation.

That all came crashing down in the carnage of 9/11. If the US leaves Afghanistan without a proper deal, history could repeat itself.

Disclaimer: The viewpoints expressed by the authors do not necessarily reflect the opinions, viewpoints and editorial policies of TRT World

AUTHOR

Rupert Stone

@RupertStone83

Rupert Stone is an Istanbul-based freelance journalist working on South Asia and the Middle East.