In psychedelic therapy, clinician-patient bond may matter most

Study links relationship strength to reduced depression for up to 1 year

READ LEARY AND ALBERT

COLUMBUS, Ohio – Drug effects have dominated the national conversation about psychedelics for medical treatment, but a new study suggests that when it comes to reducing depression with psychedelic-assisted therapy, what matters most is a strong relationship between the therapist and study participant.

Researchers analyzed data from a 2021 clinical trial that found psilocybin (magic mushrooms) combined with psychotherapy in adults was effective at treating major depressive disorder.

Data included depression outcomes and participant reports about their experiences with the drugs and their connection with therapists. Results showed that the stronger the relationship between a participant and clinician – called a therapeutic alliance – the lower the depression scores were one year later.

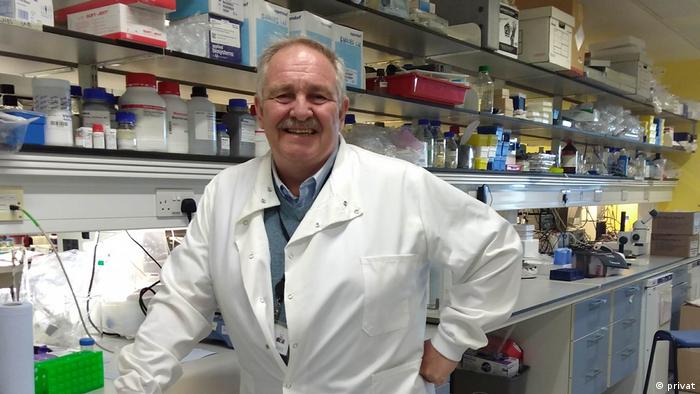

“What persisted the most was the connection between the therapeutic alliance and long-term outcomes, which indicates the importance of a strong relationship,” said lead author Adam Levin, a psychiatry and behavioral health resident in The Ohio State University College of Medicine.

Past research has consistently found that as mental health treatments changed, a trusting relationship between clients and clinicians has remained key to better outcomes, said senior author Alan Davis, associate professor and director of the Center for Psychedelic Drug Research and Education in The Ohio State University College of Social Work.

“This concept is not novel. What is novel is that very few people have explored this concept as part of psychedelic-assisted therapy,” Davis said. “This data suggests that psychedelic-assisted therapy relies heavily on the therapeutic alliance, just like any other treatment.”

The study was published recently in the journal PLOS ONE.

Twenty-four adults who participated in the trial received two doses of psilocybin and 11 hours of psychotherapy. Participants completed the therapeutic alliance questionnaire, assessing the strength of the therapist-participant relationship, three times: after eight hours of preparation therapy and one week after each psilocybin treatment.

Participants also completed questionnaires about any mystical and psychologically insightful experiences they had during the drug treatment sessions. Their depression symptoms were assessed one week, four weeks, and up to one year after the trial’s end.

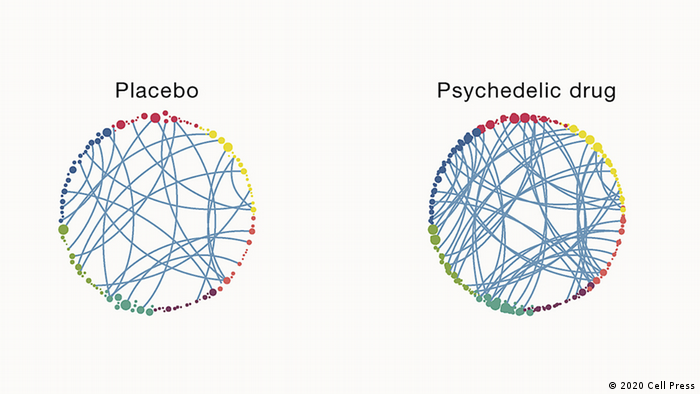

The analysis showed that the overall alliance score increased over time and revealed a correlation between a higher alliance score and more acute mystical and/or psychologically insightful experiences from the drug treatment. Acute effects were linked to lower depression at the four-week point after treatment, but were not associated with better depression outcomes a year after the trial.

“The mystical experience, which is something that is most often reported as related to outcome, was not related to the depression scores at 12 months,” Davis said. “We’re not saying this means acute effects aren’t important – psychological insight was still predictive of improvement in the long term. But this does start to situate the importance and meaning of the therapeutic alliance alongside these more well-established effects that people talk about.”

That said, the analysis showed that a stronger relationship during the final therapy preparation session predicted a more mystical and psychologically insightful experience – which in turn was linked to further strengthening the therapeutic alliance.

“That’s why I think the relationship has been shown to be impactful in this analysis – because, really, the whole intervention is designed for us to establish the trust and rapport that’s needed for someone to go into an alternative consciousness safely,” Davis said.

Considering that psychedelics carry a stigma as Schedule I drugs under the Controlled Substances Act, efforts to minimize negative experiences in future studies of their therapeutic potential should be paramount – and therapy is critical to creating a supportive environment for patients, the authors said.

This study ideally will help clearly position psychedelics treatment as a psychotherapeutic intervention moving forward – rather than its primary purpose being administration of a drug, Levin said.

“This isn’t a case where we should try to fit psychedelics into the existing psychiatric paradigm – I think the paradigm should expand to include what we’re learning from psychedelics,” Levin said. “Our concern is that any effort to minimize therapeutic support could lead to safety concerns or adverse events. And what we showed in this study is evidence for the importance of the alliance in not just preventing those types of events, but also in optimizing therapeutic outcomes.”

This work was supported by the Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research, funded by the Steven & Alexandra Cohen Foundation, the RiverStyx Foundation and private donors. It was also supported by the Center for Psychedelic Drug Research and Education (CPDRE), funded by anonymous donors.

Additional co-authors are Rafaelle Lancelotta, Nathan Sepeda and Theodore Wagener of Ohio State, and Natalie Gukasyan, Sandeep Nayak, Frederick Barrett and Roland Griffiths of the Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research at Johns Hopkins University, where Davis is an affiliate.

#

JOURNAL

PLoS ONE

SUBJECT OF RESEARCH

People

ARTICLE TITLE

The therapeutic alliance between study participants and intervention facilitators is associated with acute effects and clinical outcomes in a psilocybin-assisted therapy trial for major depressive disorder

August 6, 2024

August 6, 2024