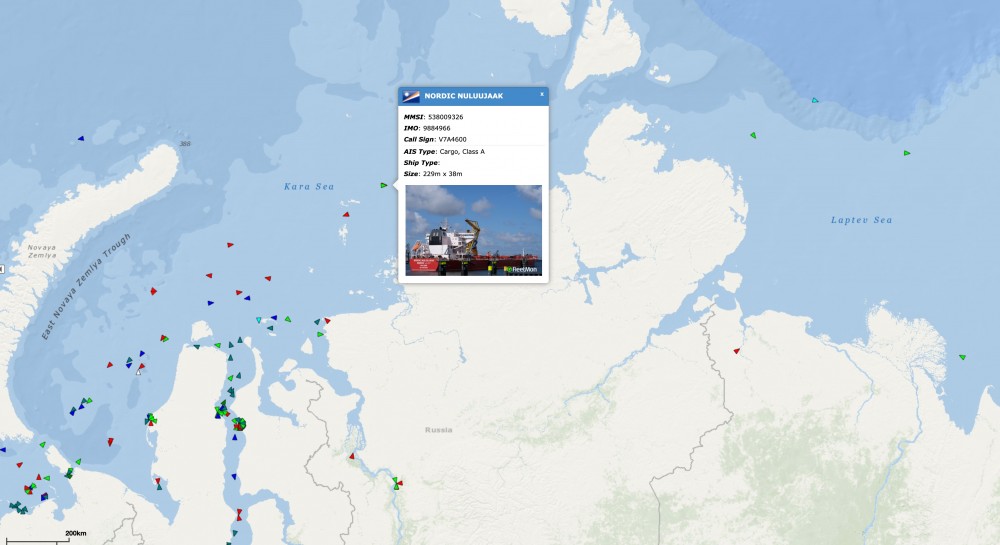

Ice-class carrier Nordic Nuluujaak makes its first voyage on the Northern Sea Route as sea-ice quickly accumulates on the far northern waters.

Bulk carrier Nordic Nuluujaak on the Northern Sea Route

By Atle Staalesen

October 25, 2021

The 229 meter long ship that was delivered by the Guangzhou International (GSI) Shipyard in May this year on the 10th of October set out from the Milne Inlet in northern Canada. On board is ore from the Baffinland Iron Mines.

The vessel sailed south through the Baffin Bay and then turned north in the Labrador Sea. By October 25th, the vessel had made it through the Barents Sea and into Russia’s Kara Sea. It is estimated to reach its destination in China on November 10.

The Nordic Nuluujaak has ice-class 1A and is the first in a fleet of four vessels to be delivered by the Chinese shipyard. It is owned and managed by Nordic Bulk Carriers, a Danish company that is part of the U.S Pangaea Logistics Solutions.

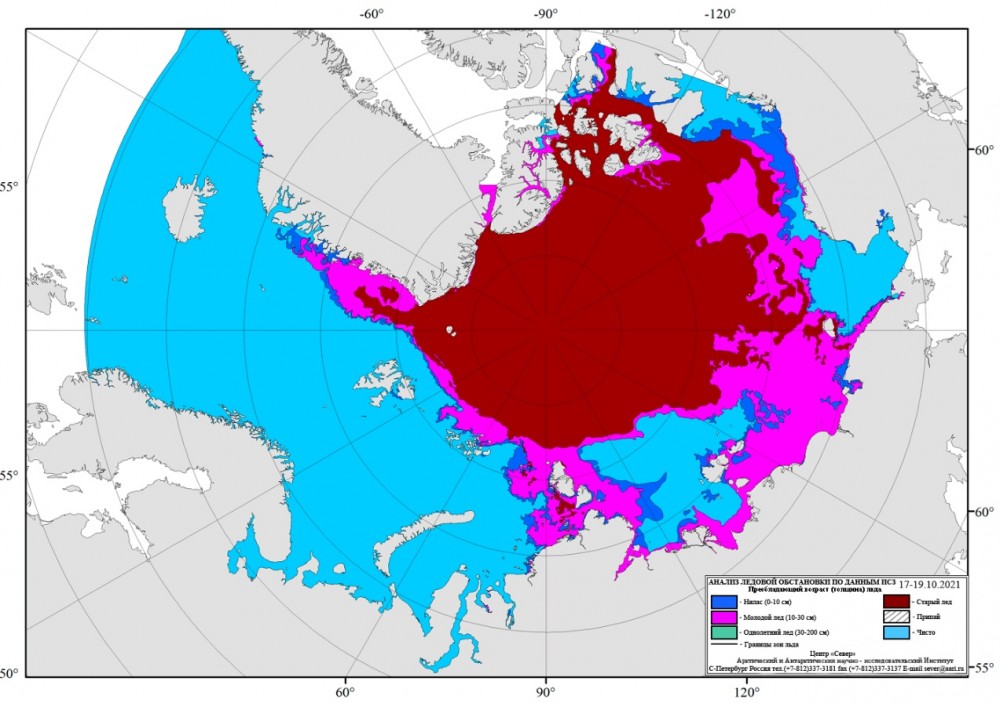

Arctic sea-ice in the period 17-19th October 2021. Map by aari.ru

It is the Arctic maiden voyage for a vessel that is designed for shipping in extreme far northern conditions.

The Nordic Nuluujaak is made for challenging Arctic conditions, says Pangaea CEO Ed Coll. It is built in close cooperation with the Baffinland Iron Mines, he told ship-technology.com.

The ice-class notwithstanding, the Nordic Nuluujaak will rarely be able to ship independently through rough and icy Arctic waters. The 1A classification allows for sailing only through one-year Arctic ice up to about 30 centimetre thick.

The Nordic Nuluujaak enters the Northern Sea Route as the Arctic waters are about to freeze and ice-maps show that parts of the Vilkitsky Strait, as well as the East Siberian Sea now has more than 30 cm thick sea-ice.

As the ship on Monday this week set course for the Vilkitsky Strait, it was accompanied by nuclear icebreaker Vaiygach.

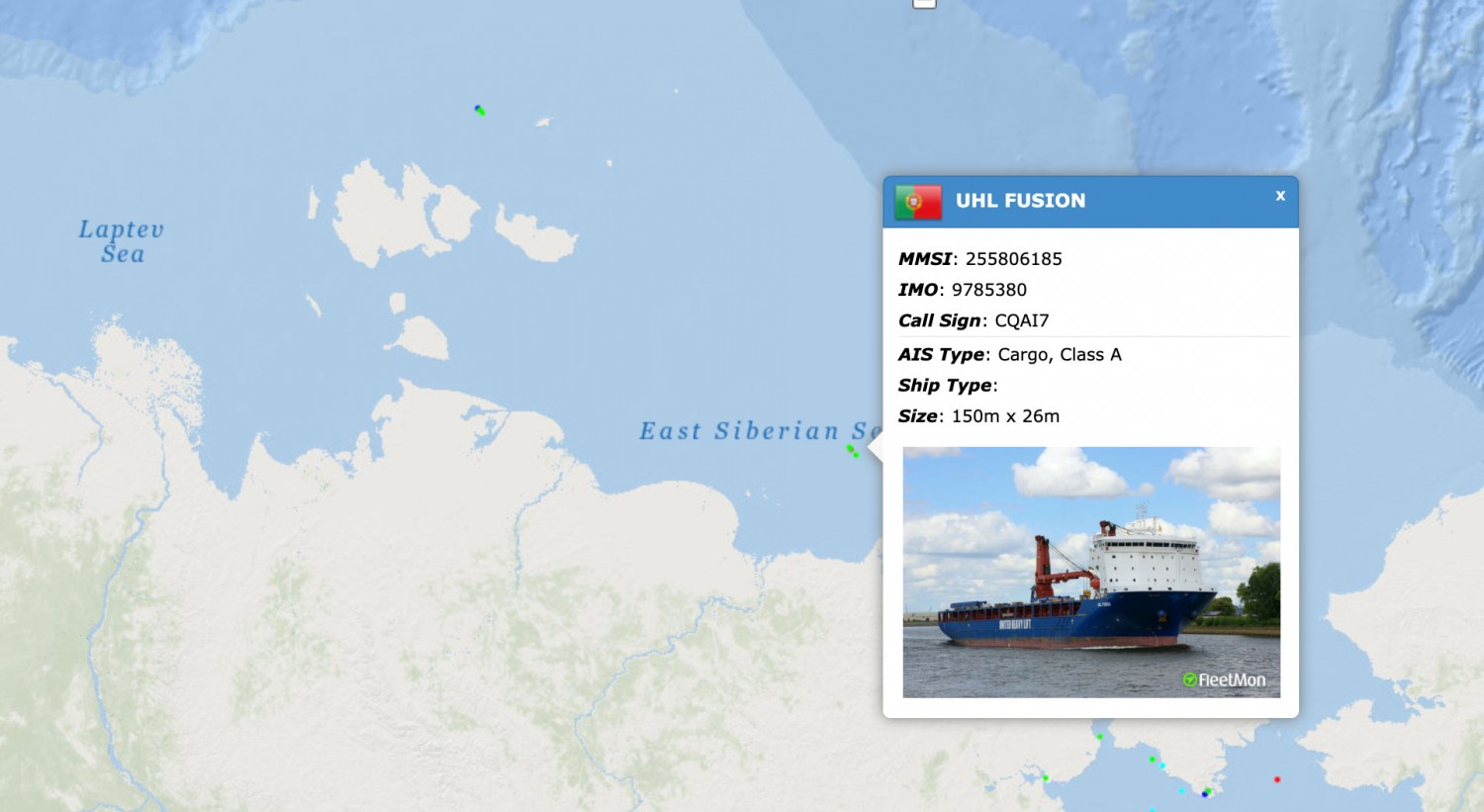

There are now only few ships left in the eastern part of the Northern Sea Route. Ship traffic maps show that there are less than 20 vessels in the waters between the Vilkitsky Strait and Bering Strait. Among them are three vessels from the United Heavy Lift. Two of them, the Uhl Flash and Uhl Faith are sailing westwards through the East Siberian Sea. None of them have high ice-class.

It is not the first time that iron ore is shipped from Canada’s far northern Milne Inlet to China through the Northern Sea Route. In November 2018, did two ships, the Nordic Olympic and Nordic Oshima sail the same route. Also in 2019 did a ship carry ore on the route.

It is the Arctic maiden voyage for a vessel that is designed for shipping in extreme far northern conditions.

The Nordic Nuluujaak is made for challenging Arctic conditions, says Pangaea CEO Ed Coll. It is built in close cooperation with the Baffinland Iron Mines, he told ship-technology.com.

The ice-class notwithstanding, the Nordic Nuluujaak will rarely be able to ship independently through rough and icy Arctic waters. The 1A classification allows for sailing only through one-year Arctic ice up to about 30 centimetre thick.

The Nordic Nuluujaak enters the Northern Sea Route as the Arctic waters are about to freeze and ice-maps show that parts of the Vilkitsky Strait, as well as the East Siberian Sea now has more than 30 cm thick sea-ice.

As the ship on Monday this week set course for the Vilkitsky Strait, it was accompanied by nuclear icebreaker Vaiygach.

There are now only few ships left in the eastern part of the Northern Sea Route. Ship traffic maps show that there are less than 20 vessels in the waters between the Vilkitsky Strait and Bering Strait. Among them are three vessels from the United Heavy Lift. Two of them, the Uhl Flash and Uhl Faith are sailing westwards through the East Siberian Sea. None of them have high ice-class.

It is not the first time that iron ore is shipped from Canada’s far northern Milne Inlet to China through the Northern Sea Route. In November 2018, did two ships, the Nordic Olympic and Nordic Oshima sail the same route. Also in 2019 did a ship carry ore on the route.

The Barents Sea is a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean, located off the northern coasts of Norway and Russia and divided between Norwegian and Russian territorial waters. Known among Russians in the Middle Ages as the Murman Sea, the current name of the sea is after the historical Dutch navigator Willem Barentsz.

Wikipedia