10-23-2023

ByChrissy Sexton

Earth.com staff writer

Geologists have long been intrigued by a missing piece of Earth’s history – a lost continent called Argoland. Around 155 million years ago, a 5,000-kilometer chunk broke off of western Australia and began its solitary drift.

The void that was left behind is marked by a basin deep below the ocean known as the Argo Abyssal Plain. But, where did Argoland actually go?

A new study from Utrecht University reveals that while Argoland might not exist as a singular mass today, it has not vanished entirely.

The journey of Argoland

Scientists have relied on the underwater Argo Abyssal Plain as evidence of Argoland’s past existence. The seabed structure suggests that the detached continent drifted northwestward, potentially towards present-day Southeast Asia.

But the mystery deepens, as the vast continent-sized footprint of Argoland is conspicuously absent beneath Southeast Asian islands. Instead, these islands sit atop smaller continental fragments, encircled by significantly older oceanic basins.

This led geologists to dive deeper into the fate of Argoland. They found that the lost continent hasn’t completely disappeared – it has simply shattered into fragments.

Earth’s hidden tales

Earth’s crust varies in weight, comprising heavier oceanic sections and lighter continental chunks. Interestingly, these lighter portions might be lurking below sea level, much like Greater Adria, another lost continent.

Greater Adria’s journey ended when it submerged into the Earth’s mantle, leaving its top layer behind, which later morphed into the mountains of Southern Europe. Argoland, by contrast, left no evidence in the form of folded rocks.

Study significance

Utrecht University geologist Douwe van Hinsbergen emphasized the significance of tracing these continents.

“If continents can dive into the mantle and disappear entirely, without leaving a geological trace at the Earth’s surface, then we wouldn’t have much of an idea of what the Earth could have looked in the geological past. It would be almost impossible to create reliable reconstructions of former supercontinents and the Earth’s geography in foregone eras,” said van Hinsbergen.

“Those reconstructions are vital for our understanding of processes like the evolution of biodiversity and climate, or for finding raw materials. And at a more fundamental level: for understanding how mountains are formed or for working out the driving forces behind plate tectonics; two phenomena that are closely related.”

Islands of information

Van Hinsbergen and his colleague Eldert Advokaat were curious about what the geology of Southeast Asia may reveal about Argoland.

“But we were literally dealing with islands of information, which is why our research took so long. We spent seven years putting the puzzle together,” said Advokaat.

“The situation in Southeast Asia is very different from places like Africa and South America, where a continent broke neatly into two pieces. Argoland splintered into many different shards. That obstructed our view of the continent’s journey.”

Fragmented continent

But then, Advokaat realized that these fragments converged at their current locations simultaneously, painting a once cohesive picture. Today, the remnants of Argoland can be found beneath the jungles of Indonesia and Myanmar.

This fragmentation was characteristic. Argoland was never a single, solid landmass. Instead, it was an ‘Argopelago,’ a collection of microcontinental chunks interspersed with older oceanic basins. This aspect aligns with other known entities like Greater Adria and Zeelandia.

An evolving planet

The investigation by Advokaat and Van Hinsbergen seamlessly links the geological systems between the Himalayas and the Philippines. Their explorations unravel why Argoland fragmented so intensely.

Around 215 million years ago, the continent underwent rapid fracturing, breaking into slender splinters. This theory was further supported through field studies on islands such as Sumatra, Borneo, and Timor.

The story of Argoland is not one of complete disappearance but of transformation. As the world continues to evolve, this lost continent serves as a compelling reminder of the ever-shifting nature of our planet.

The study is published in the journal Gondwana Research.

2023-10-23 02:24 PM by Daisy Hips

During the Early-Middle Devonian, Gondwana was a warm, flooded landmass at the South Pole, home to the now-extinct Malvinoxhosan biota. New research has revealed these species’ decline correlated with sea-level and temperature changes. Their extinction, likely due to disrupted ocean barriers and an influx of warm-water species, led to an irreversible collapse of polar ecosystems. Similar patterns have been observed in South America, underscoring the lasting sensitivity of polar regions to environmental shifts.

During the Early-Middle Devonian period, a large landmass called Gondwana—which included parts of today’s Africa, South America, and Antarctica—was located near the South Pole. Contrary to the frosty environment we see today, the climate was warmer, and elevated sea levels submerged much of its terrain.

THE MALVINOXHOSAN BIOTA MYSTERY

The Malvinoxhosan biota were a group of marine animals that thrived in cooler waters. They included various types of shellfish, many of which are now extinct. “The origin and disappearance of these animals have remained an enigma for nearly two centuries until now,” says Dr. Penn-Clarke.

The researchers collected and analyzed a vast amount of fossil data. They used advanced data analysis techniques to sort through layers of ancient rock based on the types of fossils found in them. Imagine it like sorting through layers of a cake, each with different ingredients.

Simplified diagram showing the relationship between changes in sea-level and environment with biodiversity through time in South Africa during the Early-Middle Devonian. Credit: GENUS: DSI-NRF Centre of Excellence in Palaeosciences

They then identified at least 7 to 8 distinct layers, each showing fewer and fewer types of marine animals over time. These findings were then compared with how the environment and sea levels have changed, as well as with global temperature records from that ancient period. They found that these marine animals went through several phases of declining numbers of different species, which correlated with changes in sea levels and climate. It was a difficult process.

“This research is around 12-15 years in the making, and it wasn’t an easy journey,” shares Dr. Penn-Clarke. “I was only able to overcome all the different challenges through dogged persistence and perseverance.”

THEORIES ON MARINE LIFE ADAPTATION

Their research suggests that the Malvinoxhosan biota survived during a long period of global cooling. Dr. Penn-Clarke elaborates, “We think that cooler conditions allowed for the creation of circumpolar thermal barriers—essentially, ocean currents near the poles—that isolated these animals and led to their specialization.”

As the climate warmed up again, these animals disappeared. They were replaced by more generalist marine species that are well-adapted to warmer waters. Shifts in sea levels during the Early-Middle Devonian period probably disrupted natural ocean barriers that had kept waters cooler at the South Pole.

Inset images are of common invertebrate fossils found in South Africa. Clockwise from left: Brachiopod shell bed of Australospirifer and Australocoelia, the trilobite Eldredgeia, brachiopod shells of Rhipidothyris, an ophiuroid bed. At centre is an enrolled trilobite assigned to Burmiesteria. Image credits: Geographic reconstruction after Penn-Clarke and Harper (2023), fossil photographs by Cameron Penn-Clarke and John Almond. Credit: GENUS: DSI-NRF Centre of Excellence in Palaeosciences

This allowed warmer waters from regions closer to the equator to flow in, setting the stage for marine animals that thrive in warmer conditions to move into these areas. As a result, these warm-water species gradually took over, leading to the decline and eventual disappearance of the specialized, cool-water Malvinoxhosan marine animals.

IMPACT ON POLAR ECOSYSTEMS

The extinction of the Malvinoxhosan biota led to a complete collapse in polar ecosystems, as biodiversity in these regions never recovered.

“This suggests a complete collapse in the functioning of polar environments and ecosystems to the point that they could never recover,” Dr. Penn-Clarke adds.

He likens this research to playing a game of Clue.

“It’s a 390-million-year-old murder mystery. We now know that the combined effects of changes in sea level and temperature were the most likely ‘smoking gun’ behind this extinction event,” he notes. It is still unknown if this extinction event can be correlated with known extinction events at the same time elsewhere during the Early-Middle Devonian as researchers simply do not have any real good age inferences. The mystery deepens further, and it is far from over.

Interestingly, similar declines in biodiversity controlled by sea-level changes have been observed in South America. This points to a broader pattern of environmental change affecting the South Polar region during this period and underscores the vulnerability of polar ecosystems, even in the past.

“This research is important when we consider the biodiversity crisis we are facing in the present day,” says Dr. Penn-Clarke. “It demonstrates the sensitivity of polar environments and ecosystems to changes in sea level and temperature. Any changes that occur are, unfortunately, permanent.”

Reference: “The rise and fall of the Malvinoxhosan (Malvinokaffric) bioregion in South Africa: Evidence for Early-Middle Devonian biocrises at the South Pole” by Cameron R. Penn-Clarke and David A.T. Harper, 13 October 2023, Earth-Science Reviews.

DOI: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2023.104595

The study was funded by the GENUS: DSI-NRF Centre of Excellence in Palaeosciences, the National Research Foundation, and the Leverhulme Trust.

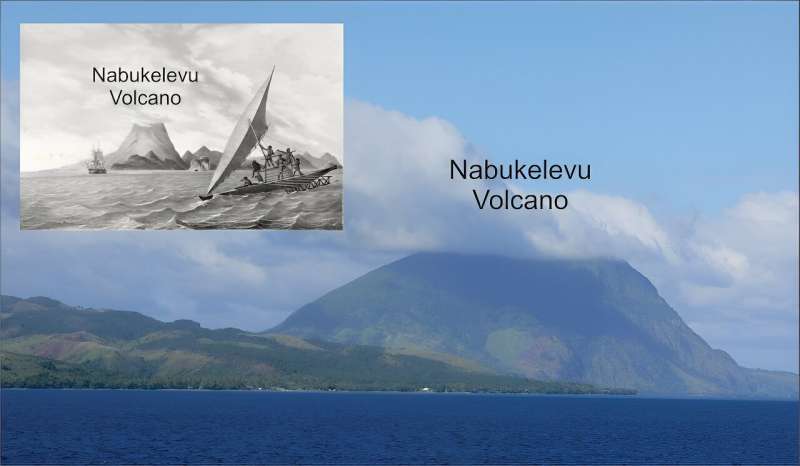

Nabukelevu from the northeast, its top hidden in cloud. Inset: Nabukelevu from the west in 1827 after the drawing by the artist aboard the Astrolabe, the ship of French explorer Dumont d’Urville. It is an original lithograph by H. van der Burch after original artwork by Louis Auguste de Sainson. Credit: Wikimedia Commons; Australian National Maritime Museum,

Nabukelevu from the northeast, its top hidden in cloud. Inset: Nabukelevu from the west in 1827 after the drawing by the artist aboard the Astrolabe, the ship of French explorer Dumont d’Urville. It is an original lithograph by H. van der Burch after original artwork by Louis Auguste de Sainson. Credit: Wikimedia Commons; Australian National Maritime Museum,