Tim Gray

Sun, July 3, 2022

NO REVOLUTION WITHOUT GENERAL COPULATION

Peter Brook, the British-born director who won Tonys and Emmys but is best known for his theater work ranging from Broadway’s “Marat/Sade” and “Irma La Douce” to experimental productions like “The Mahabarata,” has died. He was 97.

Brook’s death was confirmed by his long-time publisher, and later the BBC, on Sunday. He died in Paris, where he has lived since the 1970s. One of Brook’s final works, at 92 years old, was “The Prisoner,” which he wrote and staged in Paris as well as the Edinburgh festival and London’s National Theatre. Just this year, he staged directed “The Tempest Project” with Marie-Hélène Estienne, his long-time collaborator.

His career spanned eight decades and included opera, plays, musicals, as well as film and TV productions. After decades of bringing an unorthodox approach to traditional works from the likes of Shakespeare and Puccini, he moved to Paris, where he became even more daring and experimental: In one piece, audiences watched a French theater troupe perform in a language the actors had invented themselves.

Brook’s most memorable productions include the 1964 “Marat/Sade,” which brought dazzling theatricality to Peter Weiss’ complex play about the Marquis de Sade and the inmates at an asylum. When it transferred to Broadway in 1966, Brook won a Tony, and won a second for his startling “Midsummer Night’s Dream.”

That Shakespeare production, which debuted in England in 1970, featured a plain white-box set by Sally Jacobs and few props or set pieces. The actors appeared in factory-worker clothes or colorful baggy suits like from a Chinese circus, and swung on trapezes, spun plates and juggled while performing. The result was theater magic, illuminating Shakespeare’s text by making it seem contemporary, playful and accessible.

In Variety’s Jan. 27, 1971 review, Hobe Morrison hailed Brook as “one of the most daringly creative stage directors in the world” and predicted that it would set a standard for future productions. “Dream” featured such then-unknown actors as Patrick Stewart and Ben Kingsley, who decades later told Variety, “That production changed my life.”

Brook was born in London and educated at Westminster and Magdalen College Oxford. His first job as director was for a 1943 “Dr. Faustus” in London. From 1947 to 1950, he was director of productions at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden. Among his productions was Strauss’ “Salome” featuring sets by Salvador Dali. He later directed operas for the Metropolitan Opera and the Aix en Provence Festival.

He worked with the Royal Shakespeare Company from 1950 through 1970, including directing Paul Scofield in “King Lear,” Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh in “Titus Andronicus” and John Gielgud in “Measure for Measure.”

In his 1979 memoir “Gielgud: an Actor and His Time,” the thesp wrote, “Peter Brook has become something of a legend now, but in the 1950s at Stratford he was still very young, approachable and jolly….He did everything himself, designed the scenery, found the music, controlled the lighting.” The actor added, “I would do anything he asked me. I trust him entirely for his beautiful taste and marvelous imagination.”

Throughout his career, Brook questioned theatrical conventions and tried to break boundaries whenever possible.

In 1970, Brook and Micheline Rozan founded the International Centre for Theatre Research, a group of multinational actors, artists, dancers and musicians. It then became the International Center for Theatre Creations and established a permanent base, the Bouffes du Nord Theatre.

His theater company became less theatrical and more primal, using myth, legend, music, mime and improvisation. They generally avoided traditional Western theater venues and traveled throughout the Middle East and Africa with their work in the early 1970s. Many pieces were performed both in French and English. Sometimes the actors improvised text, and sometimes they used no text at all.

Aside from many original pieces and works by relatively unknown writers, productions there include “The Iks” by Colin Turnbull (1975); works by Chekhov, Samuel Beckett, Caryl Churchill and Athol Fugard; and adaptations of Mozart and Oliver Sachs.

Brook was influenced by the experimental theater work of Antonin Artaud, Jerzy Grotowski and Bertolt Brecht, but he said his greatest influence was Joan Littlewood, whose credits included “Oh, What a Lovely War.”

His experiments were always interesting but not always successful. Reaction was split on his 1985 “Mahabarata,” a two-part, nine-hour retelling of the epic Sanskrit poem that is India’s equivalent of Homer’s works. In a 1987 review when the production toured in the U.S., Variety called it an act of “admirable lunacy,” declaring that there were “two hours of dazzling theatrical brilliance spread out over a nine-hour running time.” The review concluded that in condensing the original, there were few concessions to Western audiences; key aspects of the Eastern mythology were never explained, and the minimalist simplicity and dialog made the tale seem flat and remote.

In 2008, he resigned as artistic director of Bouffes du Nord, handing the reins over to Olivier Mantei and Olivier Poubelle. However, Brook continued to work with them.

In 2014, he was still working hard at age 89. There was a U.S. tour of “The Suit.” He and Estienne, working with musician-composer Franck Krawczyk, adapted Can Themba’s 1950s short story set in a South African Township. The work used four actors and three musicians and everything from songs by Billie Holiday to Schubert and African songs. Also in 2014, Theatre des Bouffes du Nord premiered “The Valley of Astonishment,” the third in a series of plays that he and Estienne spent more than 20 years developing.

Brook’s films were mostly versions of his staged work: “Marat/Sade” (1967), the anti-Vietnam war piece “Tell Me Lies” (1968), “King Lear” (1971) and a 2002 TV version of “Hamlet” starring Adrian Lester. Two notable exceptions were his stark black-and-white adaptation of William Golding’s “Lord of the Flies” in 1963, and the intellectual “Meetings With Remarkable Men” (1979).

He won a 1984 Emmy Award for “La tragedie de Carmen” (based on a theater piece) and a 1990 International Emmy for “The Mahabharata” miniseries.

His 1968 book “The Empty Space,” in which he advocated continual exploration and spontaneity in theater work, became a bible of experimental theater, translated into more than 15 languages. His autobiography “Threads of Time” was published in 1998, and he also wrote “The Shifting Point” (1987) and “There Are No Secrets” (1993).

He was awarded Commander of the Order of the British Empire in 1965 and Commandeur de la Légion d’honneur (France) in 2013. Brook was also the subject of a 2014 docu, “Peter Brook: The Tightrope,” made by his son Simon and showing Brook at work with actors.

Brooke was married to actor Natasha Parry for 64 years, until her death in 2015. He is survived by his children with Parry, a son and daughter.

Manori Ravindran contributed to this story.

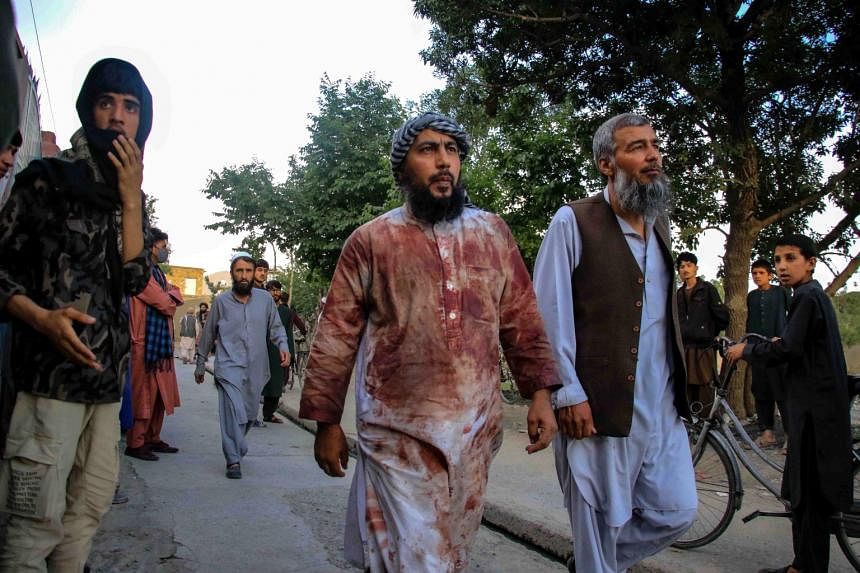

British theatre and film director, playwright and actor Peter Brook poses during a photo session at the Bouffes du Nord theatre in Paris on February 27, 2018.

Text by: FRANCE 24

Issued on: 03/07/2022 -

Peter Brook, who has died aged 97, was among the most influential theatre directors of the 20th century, reinventing the art by paring it back to drama’s most basic and powerful elements.

Brook, born in Britain but resident in France for decades, died on Saturday, French newspaper Le Monde reported, citing the director's entourage.

“Peter Brook gave us the most beautiful silences in the theatre, but this last silence is infinitely sad,” Rima Abdul Malak, France's culture minister, wrote on Twitter.

“With him, the stage was stripped back to its most vivid intensity. He bequeathed so much to us,” she added, saying he would remain “forever the soul” of the Bouffes du Nord theatre in Paris where his work was based.

Best-known for his 1985 masterpiece “The Mahabharata”, a nine-hour version of the Hindu epic, he lived in Paris from the early 1970s, where he set up the International Centre for Theatre Research at the Bouffes du Nord, an old music hall.

A prodigy who made his professional directorial debut at age 17, Brook was a singular talent right from the start.

He mesmerised audiences in London and New York with his era-defining “Marat/Sade” in 1964, which won a Tony award, and wrote “The Empty Space”, one of the most influential texts on theatre ever, three years later.

Its opening lines became a manifesto for a generation of young performers who would forge the fringe and alternative theatre scenes.

“I can take any empty space and call it a bare stage,” he wrote.

“A man walks across an empty space whilst someone else is watching him, and this is all that is needed for an act of theatre...”

It inspired actress Helen Mirren to abandon her burgeoning mainstream career to join his nascent experimental company in Paris.

African odyssey

Born in London on March 21, 1925, to a family of Jewish scientists who had emigrated from Latvia, Brook was an acclaimed director in London’s West End by his mid-20s.

Before his 30th birthday he was directing hits on Broadway.

But driven by a passion for experimentation that he picked up from his parents, Brook soon “exhausted the possibilities of conventional theatre”.

His first film, “Lord of the Flies” (1963), an adaptation of the William Golding novel about schoolboys marooned on an island who turn to savagery, was an instant classic.

By the time he took a production of “King Lear” to Paris a few years later, he was developing an interest in working with actors from different cultures.

In 1971 he moved permanently to the French capital, and set off the following year with a band of actors including Mirren and the Japanese legend Yoshi Oida on a 13,600-kilometre (8,500-mile) odyssey across Africa to test his ideas.

Drama critic John Heilpern, who documented their journey in a bestselling book, said Brook believed theatre was about freeing the audience’s imagination.

“Every day they would lay out a carpet in a remote village and would improvise a show using shoes or a box,” he later told the BBC.

“When someone entered the carpet the show began. There was no script or no shared language.”

But the gruelling trip took its toll on Brook’s company, most of whom fell ill with dysentery or tropical diseases.

Mirren later described it as “the most frightening thing I have ever done. There was nothing to hold onto”.

She parted company with Brook soon after.

He “thought that stardom was wicked and tasteless ... I just wanted my name up there”, she told AFP.

‘The best director London does not have’

Brook continued to experiment at the Bouffes du Nord, touring his productions across the globe.

His big landmark after “The Mahabharata” was “L’Homme Qui” in 1993, based on Oliver Sacks’ bestseller about neurological dysfunction, “The Man Who Mistook his Wife for a Hat”.

Brook returned to Britain in triumph in 1997 with Samuel Beckett’s “Happy Days” and his wife, the actress Natasha Parry, in the lead.

Critics hailed him as “the best director London does not have”.

After turning 85 in 2010, Brook relinquished leadership of the Bouffes du Nord but continued to direct there.

The real-life story was based on his own spiritual journey to Afghanistan just before the Soviet invasion to shoot a film called “Meetings with Remarkable Men” in 1978.

It was adapted from a book by mystical philosopher George Gurdjieff, whose sacred dances Brook performed daily for years.

Soft-spoken, cerebral and charismatic, Brook was often seen as something of a Sufi himself.

But Parry’s death in 2015 shook him. “One tries to bargain with fate and say, just bring her back for 30 seconds,” he said.

Yet he never stopped working despite failing eyesight.

“I have a responsibility to be as positive and creative as I can,” he told The Guardian. “To give way to despair is the ultimate cop-out,” he said.

(FRANCE 24 with AFP)