Muhammad Huzaifa Nizam

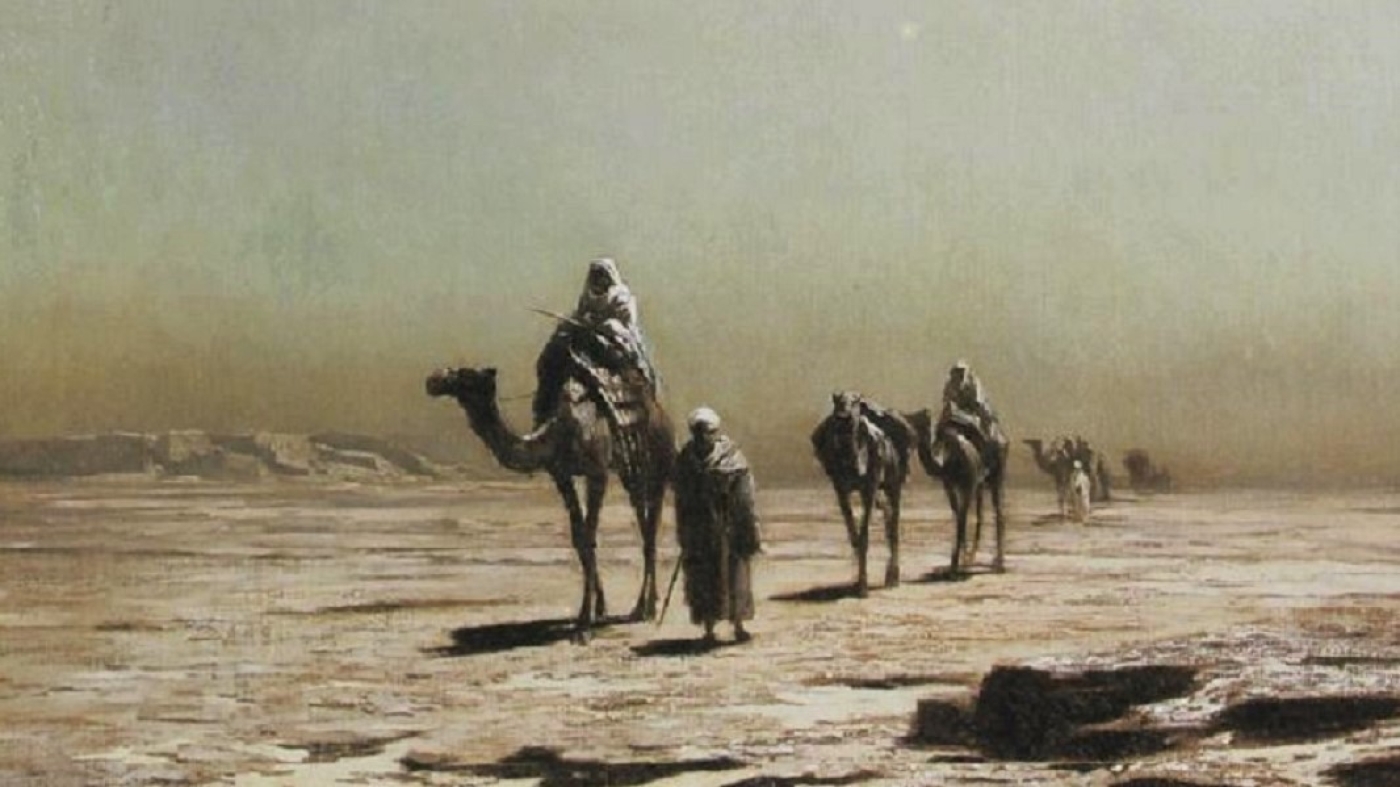

To the average observer looking from a distance, the Islamic history of modern Pakistan appears to be a kaleidoscopic mesh of ever-shifting empires, forever-marching armies, and a saga of never-ending imperial objectives.

Upon closer inspection, one finds the nature of Islamic history in the Indus Valley is intertwined with pious men, known as preachers, Sufis, saints, and by other names, who traversed the region and introduced Islam to the locals. The nature of their wanderings connected people, cultures and languages, but also sought to connect distant lands.

One such connection, laid down around 800 years ago, has survived into our modern day. It is in the form of a building in the heart of Jerusalem, established by one of Punjab’s greatest saints and poets: Baba Farid.

The fall of Jerusalem

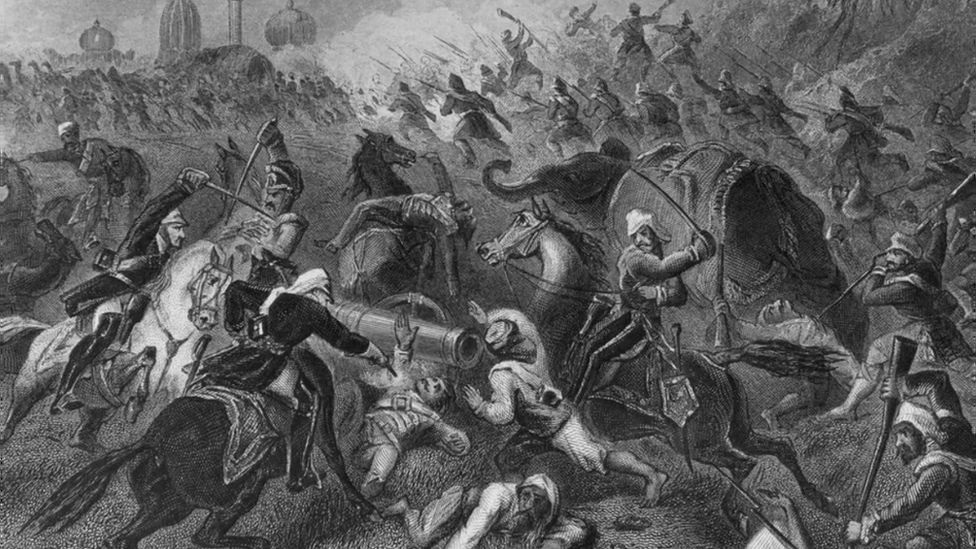

In the year 1187, soon after Crusader forces were annihilated on the plains of Hattin in Palestine, the gates of Jerusalem looked upon a victor who stood before them: Saladin. The Kurdish leader, by routing the Christian forces and annexing a large part of the Crusader state in Palestine, had fulfilled his long-term ambition of liberating the Holy Land.

But even with the physical liberation, much work was yet to be done in the spiritual domain. Decades of Crusader rule had led to many Islamic monuments being used for all kinds of purposes except for which they were made.

Hence, one of the first acts committed by Muslim forces was a ‘cleansing’ of the city, whereby Muslim monuments such as the Al-Aqsa Mosque and the Dome of the Rock (amongst many others) were rid of any remnants of Crusader rule.

A residential lodge in the holy city of Jerusalem is known by the name of Punjab’s most beloved poet, Baba Farid. How did this come to be?

With a new Muslim administration in place, the city of Jerusalem appears to have reclaimed its position among what can be considered a triad of sacred cities in Islamic history. The notion of a reunion of these holy cities, promoted by the Ayyubid monarchs, soon translated to the city becoming a place frequented by groups of Muslim pilgrims on their way to Mecca.

In addition, it became an important destination for many significant scholars, preachers and holy men of the time, who all wished to simply spend time in the holy city. While the Ayyubid administration was busy reviving Jerusalem, one such preacher whose feet would wander across the old city was still busy as a young man being tutored in the city of Multan.

The Saint from Kothewal

Born in the small village of Kothewal near Multan around 1173 CE, Farid al-Din Masud came from a family which had once enjoyed a significant position in the environs of Kabul, but which had migrated to Punjab generations ago owing to a fear of the increasing power of the nomadic Ghuzz tribes of Central Asia.

Raised in a deeply Islamic household, with a mother intent on cultivating a religious character in her son, Farid got his early Islamic education in a madrassa attached to a mosque in Multan where, amongst many things, he became proficient in Arabic and Persian.

But it was the language of the land where he lived which brought to him eternal prominence. Farid is amongst the very first people to have used the vernacular of Punjab to spread his message, which led to it travelling farther than the messages of those before him. He is, as a result, considered amongst the earliest poets of the Punjabi language.

It was in the same madrassa in southern Punjab that he came across the acclaimed Sufi Bakhtiyar Kaki, and was enrolled in the Chishti order. His unchallenged devotion towards his order and unparalleled proficiency in theological matters is said to have attracted many of the then non-Muslim groups of Punjab towards him and his message.

It was somewhere between his wanderings in Punjab and beyond to spread his message and his eventual settling down in the small town of Ajodhan (now Pakpattan) that it appears he arrived in the recently liberated city of Jerusalem.

Baba Farid and Jerusalem

Early sources on the life of Baba Farid are more or less silent on any visits or wanderings of the saint beyond his own region, which makes it difficult to reconstruct the occurrences of his stay in Jerusalem.

According to folk memory, much of the duration of the revered saint’s stay in the holy land was spent in the state of fasting and a good deal of his day would be spent praying at the Al-Aqsa Mosque or engaging in acts of devotion.

It is also said that he devoted some of his time to writing new verses of his own, which later became the bedrock of Punjabi poetry for centuries. On the few occasions he would not be occupied with praying or writing, Farid could be found meditating around one of the gates of Old Jerusalem known to the Muslims as Bab-az-Zahra and to the Christians as Herod’s Gate.

It was around this very Herod’s Gate that Baba Farid found a lodge inside a small khanqah. Also known as zawiyas, khanqahs were structures dedicated to Sufi orders, which served both as seminaries for the people associated with the order and as hospices for travellers. The immediate fall of Jerusalem saw the confiscation of many buildings belonging to the exiled Franks and turned into khanqahs, which further attracted Sufis and preachers towards Jerusalem.

It was a khanqah belonging to the Rifai order and present on a small hillock inside Herod’s Gate where Baba Farid found himself resting — unbeknownst to both him and the owners of the khanqah that his brief sojourn would completely alter the fate of this khanqah.

The Zawiya Al-Faridiya

Soon after the departure of Baba Farid, the khanqah — previously occupied by the Rifai order as a hub for their activities — quickly transformed into a hospice and a lodge for all travellers from South Asia who entered Jerusalem.

This lodge was now known locally by two names: the Zawiya Al-Faridiya (the Lodge of Farid) and the Zawiya Al-Hindiya (the Lodge of Hind). Much like its two popular names, there are two popular tales which have survived to narrate how this change of association came to be, with one tale emphasising how the Chishti order of Sufism, to which Baba Farid belonged, eventually went on to buy the khanqah in the name of the saint.

The other speaks of how the then Ayyubid authorities of Jerusalem recognised the spiritual standing of the saint and, in this regard, decided to grant the zawiya either to Baba Farid directly or to some of his disciples who later visited the city.

With the turn of the centuries, the region saw much political upheaval, but the lodge appears to have managed to survive it all. It possibly remained a witness to the various later Crusades launched by the Europeans, to the Mongol horsemen galloping towards their ultimate doom in the plains of Ain Jalut at the hands of the Mamluks, and to the later march of the Ottomans who eventually defeated the Mamluks and established Ottoman rule in Palestine for centuries.

Despite all the conflicts and turmoil, the lodge finds itself in the small list of structures which, albeit in a decrepit state, managed to stay erect till the very end of direct Muslim control of the region.

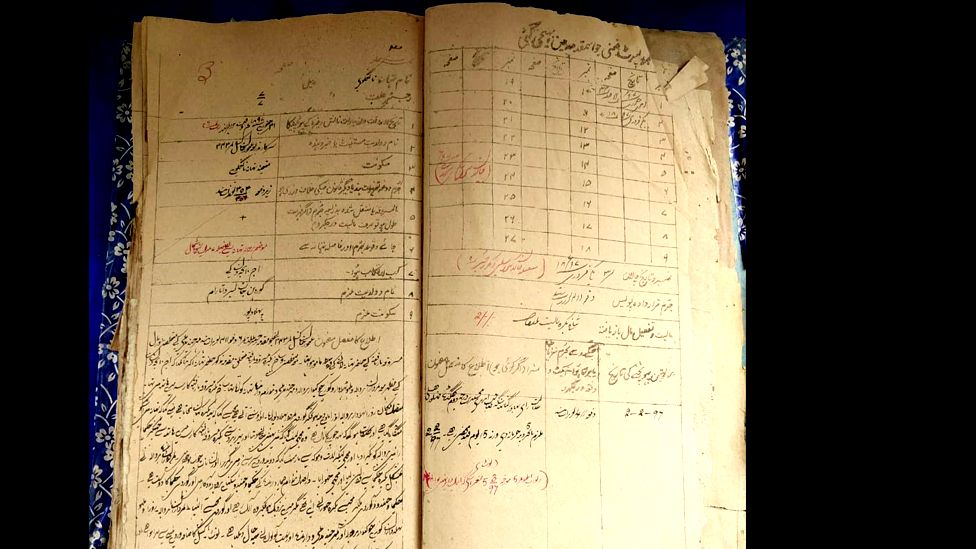

Not much knowledge exists about the sheikhs and heads of the lodge during the many intervening centuries, but some documents from the Ottoman era which have survived down to our time point towards a connection of the lodge to Punjab in particular.

A document from 1681, revealed to an Indian researcher Navtej Sarna by the current sheikh, reveals details of a dispute about the leadership of the lodge between a Muslim carrying the nisbah Al-Hindi and a Muslim from Multan in southern Punjab.

Another document related by the same source provides a reference towards another Muslim from Punjab, as it speaks of a certain sheikh named Ghulam Mohammad Al-Lahori who is credited to have engaged with the Ottoman administration in 1824 and successfully conducted a transfer of properties, which resulted in the addition of seven rooms, two water tanks, and a courtyard to the original lodge.

It seems the lodge enjoyed prominence and stability under sheikhs from across South Asia during the many centuries of Ottoman rule, but the story takes a drastic turn when the Ottoman empire itself finally gave way in 1919.

A turbulent change of owners

The Ottoman Empire, which at the time was known as ‘the sick man of Europe’, was eventually dismembered by the end of World War I, with much of its former territories in the Middle East becoming occupied by European forces.

Palestine remained under the watchful shadow of the Union Jack and, thus, so did Jerusalem and the lodge of Farid. As the British occupation of Palestine set in, with time, the position of the Grand Mufti of Palestine was established by the Europeans, who also greatly strengthened it in pursuit of effective management.

By 1921, the position had come down to the hands of one Amin Al-Husayni, who undertook massive rebuilding projects and renovations in Jerusalem to bring it once again to the centre stage of the Muslim world. To accumulate funds for these projects, the Grand Mufti sent envoys to any and every possible Muslim patron across the world, many of whom at the time could be found in the form of Muslim rulers of princely states in British India.

It was during this very visit that the envoys from Jerusalem informed the leaders of the Indian Khilafat Movement of the existence of an ‘Indian Lodge’, which was in a decrepit state and desperately required a capable Indian person to look after it.

This Indian lodge was, in fact, the same lodge of Farid, and chosen by the Indian Muslim leaders to breathe a new life into it was a young man from Saharanpur in Uttar Pradesh, named Khwaja Nazir Hasan Ansari.

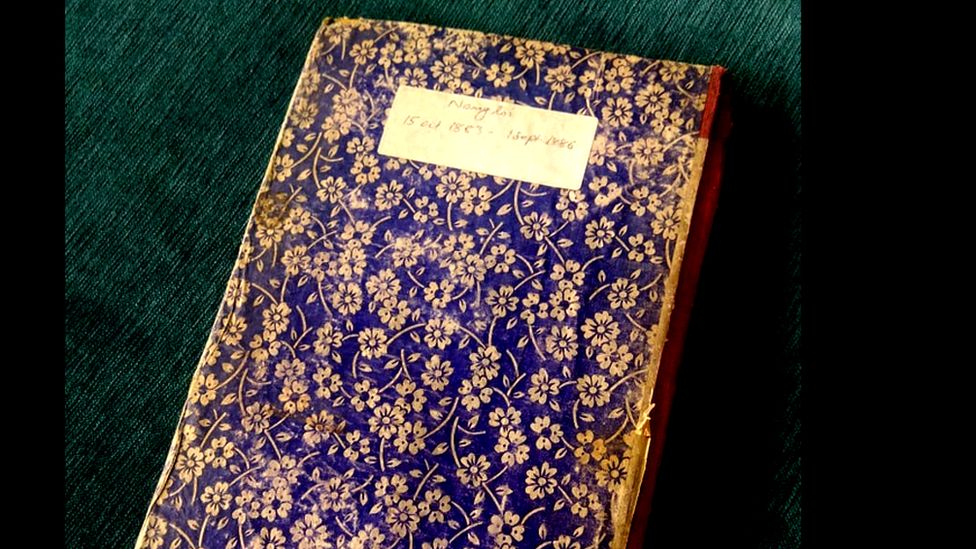

Thus, the lodge came under the administration of the Ansari family of Uttar Pradesh, who still look after it. Nazir Ansari got a hold of the lodge in 1924 and, in a brief time, managed to completely renovate it and brought it to such a credible state that, for the next 15 years, it gave sanctuary to thousands of travellers and pilgrims from British India.

With the outbreak of World War II in 1939, the lodge, which was housing pilgrims, now offered sanctuary to Muslim and non-Muslim soldiers of British India alike fighting in North Africa. It would later resume its duties towards pilgrims in the post-war period, until the British withdrew and the frenzy of war began once again.

Conclusion

The end of the Second World War in 1945 was soon followed by the withdrawal of British authorities from both British India and the British Mandate of Palestine, with ironically two new states forming in both regions that immediately went to war.

With the exodus of the Palestinians, the war with the nascent Israeli state, and the refugees pouring in from West Jerusalem, the lodge eventually could not run on its own and help was sought. For this, Nazir Ansari reached out to the Indian embassy in Egypt and established an official relationship between the lodge of Farid and the newly independent Indian state.

Today, many decades later, the lodge proudly displays two Indian flags at its entrance, with a nameplate reading ‘Indian Hospice’. And though one could debate if the state of Pakistan has much more of a right to a connection with the lodge — owing to Baba Farid’s ancestry being in this country — it cannot be so, amongst a plethora of reasons, simply because Pakistan has no official ties with the state of Israel.

Perhaps, in the future, a shift in the circumstances of the Palestinians could lead to a linkage being established between the lodge and the homeland of the person who established it. For now, it suffices to know that there does exist in the heart of one of the world’s most important cities, a corner occupied by a piece of Punjab.

The writer’s areas of interest are Pakistan’s lesser known history and folklore. He is a Chitrali based in Peshawar. X:MHuzaifaNizam

Published in Dawn, EOS, October 15th, 2023