Where rural and urban Americans divide on the environment—and where there's common ground

Rural and urban Americans are divided in their views on the environment, but common ground does exist, says a new report led by Duke University's Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions.

"The urban/rural divide on the environment is real, but it centers not on differences in how much people value environmental protection but on divergent views toward government regulation," said lead author Robert Bonnie, executive in residence at the Nicholas Institute and a former undersecretary for natural resources and environment at the U.S. Department of Agriculture. "Rural Americans, across party lines, are less supportive of governmental oversight on the environment than their urban/suburban counterparts."

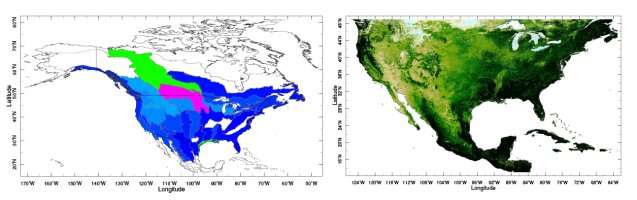

The study was conducted over two years by the Nicholas Institute with assistance from the University of Rhode Island, the University of Wyoming, Hart Research Associates and New Bridge Strategy. It involved extensive outreach to rural constituencies, including a national survey of more than 2,000 registered voters, focus groups with more than 125 rural voters and in-depth interviews with 36 rural leaders.

Rural Americans have an outsized impact on national environmental policy, from strong representation in the halls of Congress to management of vast swaths of lands and watersheds, the authors note.

Polling results indicated broad support for conservation and environmental protection among both rural and urban/suburban voters. The study also found rural voters to be relatively knowledgeable about environmental policies and the potential economic trade-offs that come with them.

"Americans living in rural communities showed a powerful commitment to protecting the environment, motivated in large part by a strong place identity and desire to maintain local environmental resources for future generations," said study co-author Emily Diamond, assistant professor at the University of Rhode Island.

Rural voters significantly diverged from urban and suburban voters over attitudes toward federal regulation, the study found. In the polling, rural voters across political parties expressed more skepticism for government policies. Participants in focus group conversations often voiced strong support for conservation and environmental protection in the abstract but raised concerns about the impacts and effectiveness of specific policies.

Climate change proved to be another dividing line between rural and urban/suburban voters.

"Our focus groups and interviews echoed this sense that rural opposition to climate change policies may be tied to negative experiences they have had with other federal environmental regulations," Diamond said.

"Climate change is a polarizing issue in rural America, but there is a path forward that can win rural support," Bonnie added. "Our study shows that engagement and collaboration with rural stakeholders will be important to winning over rural support."

There is no quick fix to bridging the urban/rural divide on environmental policies, the authors said. They recommend that policymakers, environmentalists and conservation groups engage more with rural communities when developing policies that could affect them. The authors also suggest federal policies—especially for addressing climate change—are more likely to gain rural voters' support if they allow for state and local partnerships and collaboration with rural stakeholders.

Other key recommendations include:

- Working with trusted messengers, such as farmers, ranchers, and cooperative extension services, to convey information about environmental policies to local stakeholders

- Improving scientific outreach to rural communities

- Offering opportunities to address environmental policy priorities in a way that is compatible with rural economiesNew poll shows rural health may be powerful issue in 2020 election

More information: Understanding Rural Attitudes Toward the Environment and Conservation in America, nicholasinstitute.duke.edu/publications/understanding-rural-attitudes-toward-environment-and-conservation-america