Researchers study how birds retweet news

THEY DON'T USE TWITTER

Every social network has its fake news. And in animal communication networks, even birds discern the trustworthiness of their neighbors, a study from the University of Montana suggests.

The study, recently published in the top science journal Nature, is the culmination of decades' worth of research from UM alumni Nora Carlson and Chris Templeton and UM Professor Erick Greene in the College of Humanities and Sciences. It sheds a new light on bird social networks.

"This is the first time people have shown that nuthatches are paying attention to the source of information, and that influences the signal they produce and send along," Greene said.

Carlson, Templeton and Greene shared an interest in trying to crack the Rosetta Stone of how birds communicate and collected bird calls over the years.

Each bird species has a song, usually sung by the males, for "letting the babes know 'here I am,'" Greene said, as well as staking out real estate. Their loud and complex calls usually ring out during breeding season.

But for warning calls, each sound stands for a specific threat, such as "snake on the ground," "flying hawk" and "perched hawk." The calls convey the present danger level and specific information. They also are heard by all species in the woods in a vast communication network that sets them on high alert.

"Everybody is listening to everybody else in the woods," Greene said.

In the study, Greene and his researchers wanted to determine how black-capped chickadees and red-breasted nuthatches encode information in their calls.

In bird communication, a high-pitched "seet" from a chickadee indicates a flying hawk and causes a strong reaction—other birds go silent, look up and then dive in the bushes. Alarm calls can travel quickly through the woods. Greene said in previous experiments they clocked the speed of the calls at 100 miles per hour, which he likens to the bow wave on a ship.

"Sometimes birds in the woods know five minutes before a hawk gets there," Greene said.

A harsh, intensified "mobbing call" drives birds from all species to flock together to harass the predator. When the predator hears the mobbing call, it usually has to fly a lot farther to hunt, so the call is very effective.

"The owl is sitting in the tree, going, 'Oh crap!" Greene said.

Greene calls it "social media networks—the original tweeting."

For the study with chickadees and nuthatches, the researchers focused on direct information—something a bird sees or hears firsthand—versus indirect information, which is gained through the bird social network and could be a false alarm.

"In a way, it kind of has to do with fake news, because if you get information through social media, but you haven't verified it, and you retweet it or pass it along, that's how fake news starts," Greene said.

Nuthatches and chickadees share the same predators: the great-horned owl and the pygmy owl. To the small birds, the pygmy owl is more dangerous than a great-horned owl due to its smaller turning radius, which allows it to chase prey better.

"If you are eating something that's almost as big as you are, it's worth it to go after it," Greene said.

Using speakers in the woods, the researchers played the chickadee's warning call for the low-threat great-horned owl and the higher-threat pygmy owl to nuthatches. The calls varied by threat level—great-horned owl versus pygmy owl—and whether they were direct (from the predators themselves) or indirect (from the chickadees).

What they discovered about the nuthatches was surprising.

Direct information caused the nuthatches to vary their calls according to the high threat and the low threat. But the chickadee's alarm call about both predators elicited only a generic, intermediate call from the nuthatch, regardless of the threat level.

Greene said the research points to the nuthatch's ability to make sophisticated decisions about stimuli in their environment and avoid spreading "fake news" before they confirm a predator for themselves.

"You gotta take your hat off to them," Greene said. "There's a lot of intelligence there."

The research, conducted by Carlson, Templeton and Greene around Montana and Washington throughout the years, wasn't without challenges.

Most of the set up happened during winter, and nuthatches had to be isolated from chickadees to ensure the warning calls were not a response to witnessing chickadees going crazy. Often a chickadee would appear after everything was set up, and the researchers had to take everything down and try a new location.

"It's quite hard to find nuthatches without chickadees somewhere in the area," Greene said. "That was the most difficult part—to find these conditions out in the wild."

But the results were worth the work.

Greene said the nuthatch study ultimately helps researchers better understand how animal communication networks work and how different species decode information, encode info and pass it along.

"We kind of wish people behaved like nuthatches," Greene said.Squirrels listen in to birds' conversations as signal of safety

More information: Nora V Carlson et al, Nuthatches vary their alarm calls based upon the source of the eavesdropped signals, Nature Communications (2020). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-020-14414-w

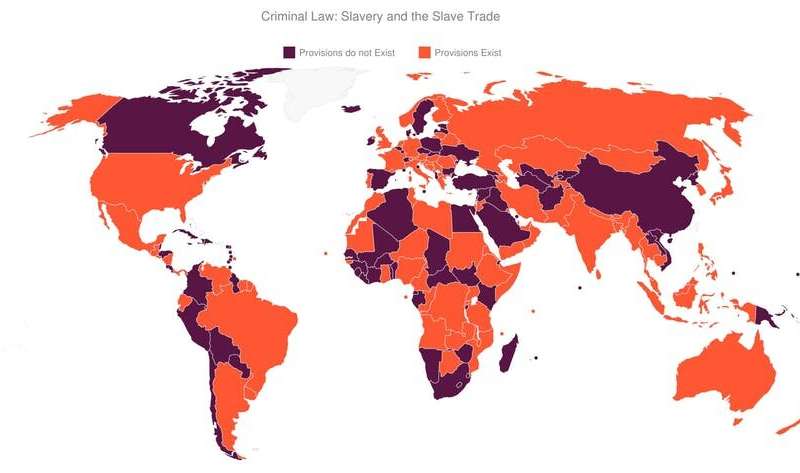

States in which slavery is currently criminalised. Credit: Katarina Schwarz and Jean Allain

States in which slavery is currently criminalised. Credit: Katarina Schwarz and Jean Allain