The Wuhan Institute of Virology previously conducted controversial experiments to test what could make coronaviruses more dangerous to humans, but scientists have ruled out that SARS-CoV-2 is a product of genetic engineering.

Peter Aldhous BuzzFeed News Reporter May 6, 2020

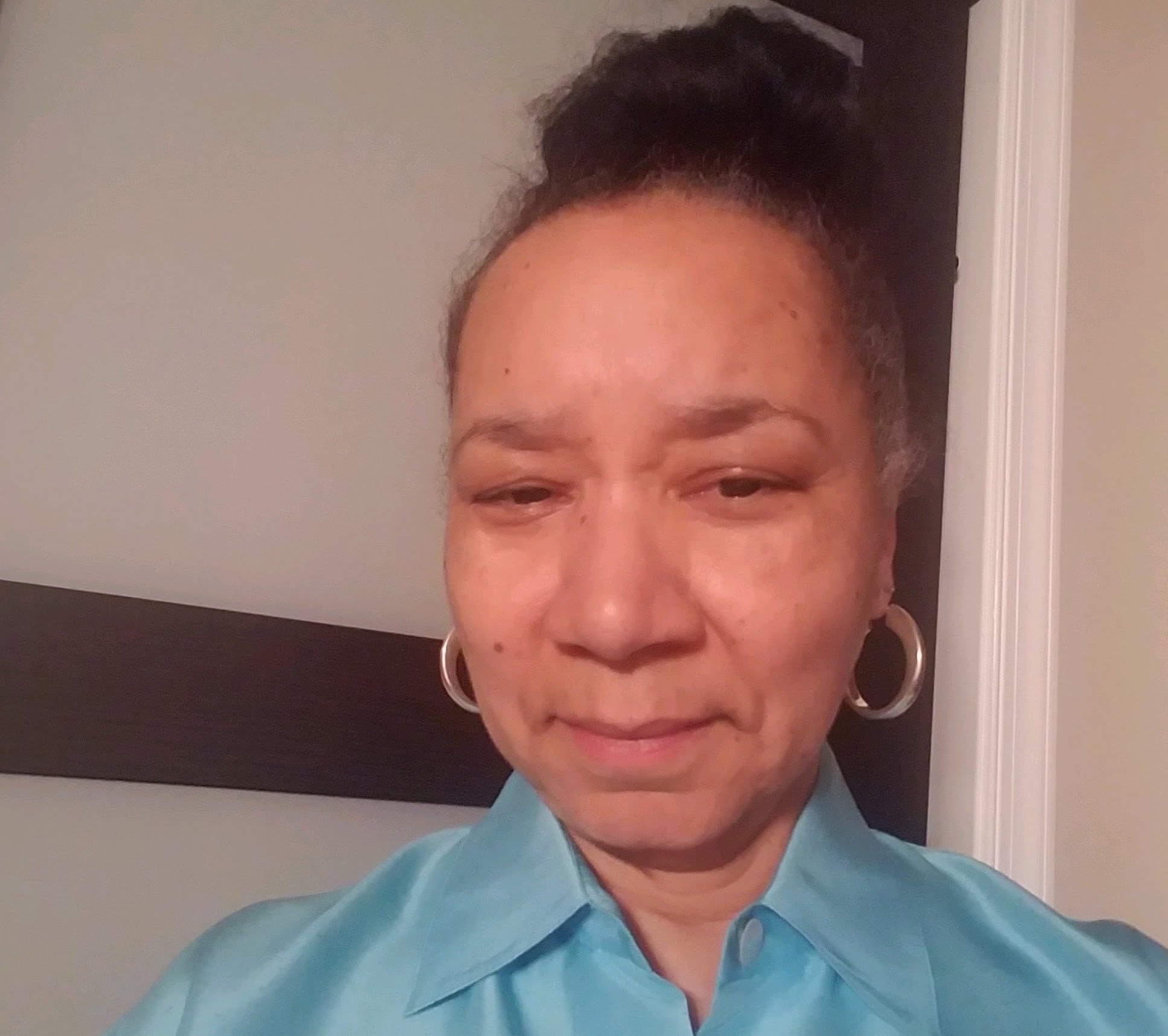

Johannes Eisele / Getty Images

Chinese virologist Shi Zhengli (left) at the Wuhan Institute of Virology

President Donald Trump and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo have been beating a drumbeat of blame for COVID-19: Both claim that the novel coronavirus behind the pandemic came from a lab in Wuhan, China.

Asked on April 30 by a reporter if he had seen evidence that the virus emerged from the Wuhan Institute of Virology, Trump responded: “Yes, I have. Yes, I have,” going on to accuse the World Health Organization of being “like the public relations agency for China.”

On May 3, Pompeo said on ABC News that there was “enormous evidence” that the virus originated in a Wuhan lab. Both men claimed they were “not allowed” to reveal what this evidence was, suggesting their information came from classified intelligence.

Before being seized on by Trump and Pompeo, the theory that the virus came from a Wuhan lab had been promoted by right-wing media outlets including Fox News and the Washington Examiner, as well as the Epoch Times, a publication linked to the Chinese dissident religious group Falun Gong.

While scientists can’t eliminate the possibility of a lab escape entirely, the evidence suggests that the virus most likely evolved naturally, probably spreading to people in a seafood market in Wuhan where live animals were also on sale. Anonymous briefings from international intelligence officials have also suggested that the Wuhan Institute of Virology is unlikely to be the source of COVID-19.

Despite the questions and rumors, there’s quite a bit we do know about the research that was done at the Wuhan lab and why it’s unlikely to be the origin of the new coronavirus. Here’s what we know:

The Wuhan lab began studying bat coronaviruses in 2004 after SARS.

The head of the lab, which is operated by the Chinese Academy of Sciences, is virologist Shi Zhengli. (Shi did not immediately respond to queries about her work from BuzzFeed News; a representative said by email that they would seek permission from the Chinese Academy of Sciences for her to be interviewed.)

Popularly known as China’s “bat woman,” Shi studies the many different coronaviruses circulating in bats across China and beyond, trying to assess the risk that they could jump into people and cause a pandemic like COVID-19.

That became a priority after SARS, a respiratory illness caused by another coronavirus, which appeared in China in 2002 and spread to more than two dozen countries, killing 774 people. MERS, a similar disease caused by yet another coronavirus, emerged in Saudi Arabia in 2012, spread to 27 countries, and has killed 858 people.

Both SARS and MERS are thought to have spread to people from animals — civets in the case of SARS and dromedary camels for MERS. But bats are believed to be the natural reservoir for these and other potentially pandemic coronaviruses, circulating the viruses in their populations and occasionally passing them to other species. And so from 2004 onward, Shi searched caves across China for colonies of roosting bats, taking swabs from the animals and collecting their droppings to examine the coronaviruses they carry.

Shi’s team has since identified dozens of coronavirus variants in bats, constructing an evolutionary tree of how they are related to one another based on the sequences of the RNA that makes up their genetic material, and showing that viruses from distinct branches of this tree seem to be found in different parts of China. In 2013, Shi’s group identified two coronavirus strains from horseshoe bats that were 95% genetically similar to the virus that caused SARS, providing the strongest evidence that, while the virus likely jumped to humans via a civet, bats were the ultimate origin of the virus.

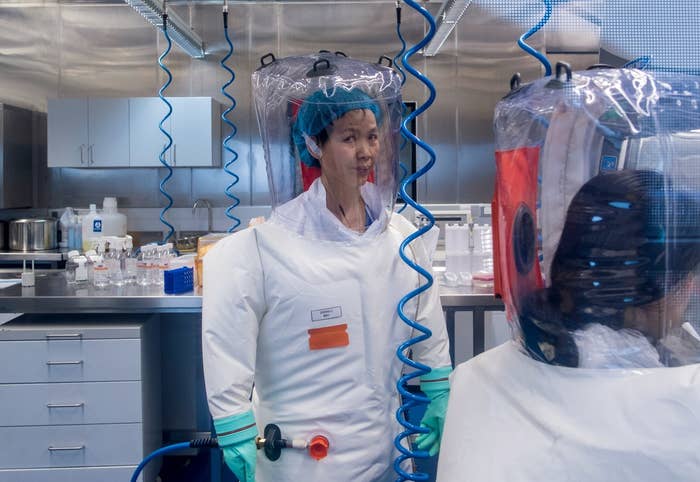

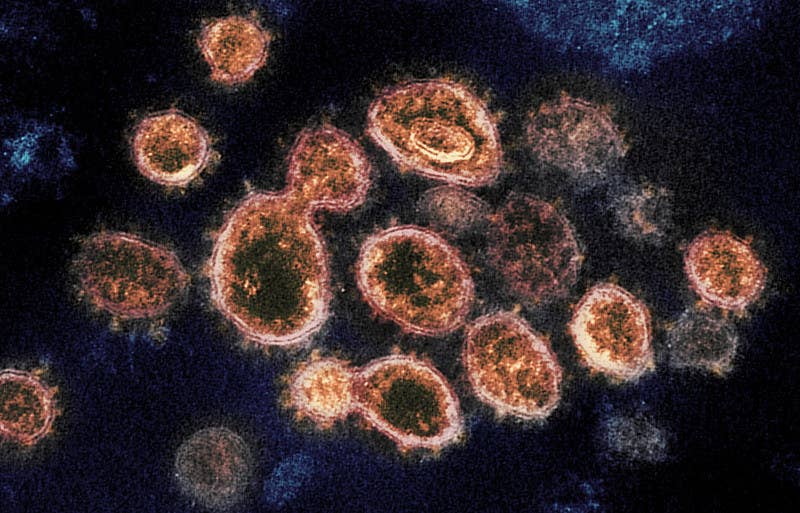

Shi’s team has also studied the genetic mutations that seem to make bat coronaviruses more likely to cross over into people, focusing in particular on the gene that encodes its “spike protein.” The halo of spikes on the surface of coronaviruses gives them their signature crownlike appearance when viewed through an electron microscope. The ability of bat coronaviruses to infect human cells seems to depend on the interaction between the spike protein and a receptor called ACE2 on the surface of cells in the lungs.

Menahem Kahana / Getty Images

A horseshoe bat

The lab previously conducted controversial experiments to test what could make coronaviruses more dangerous to humans.

Most controversially, Shi’s research on the spike protein has involved experiments that some scientists view as unacceptably risky: deliberately genetically engineering viruses to study what makes them more dangerous.

In 2015, Shi and Ralph Baric, a virologist at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, described experiments in which they engineered the spike protein from one of Shi’s SARS-like horseshoe bat coronaviruses into another coronavirus that had already been adapted to infect mice. The engineered virus replicated easily in human cells, and antibodies and vaccines developed against the SARS virus were relatively ineffective in protecting mice from infection.

Shortly after these experiments were run, the US government placed a moratorium on so-called gain-of-function research to make pathogens more dangerous. The ban was eventually lifted in December 2017, but the research remains controversial. “As the world reels from the impacts of the present pandemic, it should be clear to anyone without a conflict of interest that creating new potential pandemic pathogens is unwise,” Richard Ebright, a molecular biologist at Rutgers University in New Jersey, told BuzzFeed News by email.

Baric did not respond to requests from BuzzFeed News to discuss his work with Shi. BuzzFeed News could find no evidence that Shi has performed gain-of-function studies since.

Scientists are certain that the coronavirus that causes COVID-19 was not genetically engineered.

In March, an international team of virologists led by Kristian Andersen of the Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California, published an analysis of the genetic sequence of SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19. They concluded: “Our analyses clearly show that SARS-CoV-2 is not a laboratory construct or a purposefully manipulated virus.”

If the virus had been deliberately engineered, scientists would expect to see sequences that are suspected to make coronaviruses more dangerous spliced into the backbone of a viral strain commonly used for experiments of this type. Instead of this smoking gun, SARS-CoV-2 has mutations all along its genetic sequence that experts would have had no prior reason to guess would be associated with a potentially pandemic virus. This result is what they would expect to see if the virus had evolved naturally.

“I am quite sure SARS-CoV-2 was not lab-synthesized, judging by the sequence,” Susan Weiss, a coronavirus expert at the University of Pennsylvania who was not involved in Andersen’s study, told BuzzFeed News by email. “It seems impossible that someone could figure out how to make a virus with these properties.”

It’s also highly unlikely the virus escaped the Wuhan lab by accident — though we can’t rule out the possibility.

Such “lab escape” accidents are not unknown. They happened several times during the SARS epidemic, with accidental infections occurring at labs in Singapore, Taiwan, and China. The most serious incidents were at the Chinese National Institute of Virology in Beijing, where the virus escaped and infected people on several occasions.

Scientists also now think that the 1977 reemergence of the H1N1 flu was the result of a laboratory accident. H1N1, the subtype of flu that caused the 1918 flu pandemic, hadn’t been seen in the wild since 1957. But in 1977, an H1N1 virus turned up in China and Russia. It spread across the world, but fortunately only affected younger people who had not been exposed to similar viruses before and proved less deadly than regular seasonal flu.

The 1977 pandemic H1N1 was very similar to viruses sampled from flu patients around 1950. Because viruses typically accumulate genetic mutations as they replicate, making them slowly change over time, the explanation for this uncanny similarity was that the virus had been kept frozen for years in a laboratory. “We and others estimated that it was 27 years in the freezer,” Joel Wertheim of the University of California, San Diego, who has studied the origins of the 1977 flu pandemic, told BuzzFeed News

The closest known virus to SARS-CoV-2 is called RaTG13. Isolated by Shi’s team from a horseshoe bat in Yunnan province in southern China, hundreds of miles away from Wuhan, RaTG13 has a genetic sequence that is 96% similar to SARS-CoV-2. While that might sound like a close match, it means the two viruses are probably separated by “decades of evolution,” according to Wertheim.

Andersen’s team also considered the possibility that the particular combination of mutations seen in SARS-CoV-2 arose as a result of growing it in cell cultures in the lab. But they decided this was unlikely. Some of the mutations, they noted, seemed to be the result of interacting with an animal’s immune system, while the part of the spike protein that binds to human cells via the ACE2 receptor was similar to sequences found in coronaviruses in pangolins. Together, this evidence suggested a natural origin, they concluded.

Shi has said that she initially worried that the virus might have escaped from her lab, but found no close match among her samples. “That really took a load off my mind,” she told Scientific American. “I had not slept a wink for days.”

Proponents of the lab-origin theory have also pointed out that only 27 of 41 patients described in a study of the initial outbreak in Wuhan had a direct connection to the seafood market that has been blamed for the emergence of COVID-19. But unlike the accidents with SARS, there is no evidence that anyone connected to the Wuhan Institute of Virology was among the early patients.

While highly unlikely, scientists can’t rule out that SARS-CoV-2 was secretly studied in a lab and accidentally released. The brief appearance in mid-April of online notices and a Chinese government directive suggesting that research in China on the origins of COVID-19 must be “strictly and tightly managed,” first reported by CNN, has added to suspicion of a cover-up by Chinese authorities.

NIAID / Via Flickr: nihgov

SARS-CoV-2

US intelligence is looking into whether the virus escaped from the lab, but the international intelligence community suggests that’s “highly unlikely.”

Speculation that COVID-19 may have been released from the Wuhan Institute of Virology grew after Washington Post columnist Josh Rogin reported on April 14 that he had seen a 2018 US diplomatic cable warning about “inadequate safety” at the facility.

However, Dennis Carroll, a virologist and former official with the US Agency for International Development, which has funded Shi’s work, has questioned the importance of the cables, which he saw while working in Beijing. “I didn’t place an enormous amount of weight on the observations that were made because they were not part of a critical, standardized evaluation,” Carroll told Science.

On April 30, after Trump started to blame the Wuhan lab for COVID-19, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence issued a statement saying that “the entire intelligence community” agreed with the scientific consensus that the virus was not genetically modified, but was leaving open the possibility that it had been accidentally released from a lab.

“The IC will continue to rigorously examine emerging information and intelligence to determine whether the outbreak began through contact with infected animals or if it was the result of an accident at a laboratory in Wuhan,” the statement went on.

The same day, the New York Times reported that senior Trump administration officials had been applying pressure to US intelligence agencies to hunt for evidence to support the unsubstantiated theory.

Australian officials told the Sydney Morning Herald that a dossier shared among political leaders in the Five Eyes coalition — the US, UK, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand — linking the coronavirus to a Wuhan laboratory was mostly based on news reports and contained no original intelligence.

Anonymous officials from the Five Eyes coalition told CNN that an intelligence assessment shared in the network suggests the lab-release theory is “highly unlikely.”

Nevertheless, the fight over the Wuhan lab has dealt a blow to research into COVID-19 and other potentially pandemic viruses.

The most obvious casualty is a grant to Peter Daszak of the EcoHealth Alliance in New York City from the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), given to understand the risks of coronaviruses spreading from bats to people.

Daszak has worked with Shi to study China’s bat coronaviruses, including the 2013 paper on the two horseshoe bat viruses similar to the SARS virus. But on April 24, the grant to Daszak was abruptly terminated, as first reported by Politico. That happened just one week after Trump was asked a question about the funding for the Wuhan lab at a press conference and said: “We will end that grant very quickly.”

In 2016, Shi and Daszak also described a “fast and cost-effective method” for genetically engineering coronaviruses, funded in part by the NIAID grant. But it’s unclear that this aspect of the work had anything to do with the termination of the grant. Instead, emails obtained by Science from the National Institute of Health’s deputy director for extramural research suggested that the decision to terminate the grant was made because of safety issues at the lab, though no evidence was given to support that claim.

Other scientists have described the termination of the grant as a “horrible precedent” that will hamper efforts to understand the threat of future pandemics.

“Our work on the NIAID funding was to assess the risk of bat-origin coronaviruses getting into people, causing sickness and emerging globally,” Daszak told BuzzFeed News by email. “The real risk is out in nature, not in the lab.”

Scientists Haven’t Found Proof The Coronavirus Escaped From A Lab In Wuhan. Trump Supporters Are Spreading The Rumor Anyway.

Ryan Broderick · April 22, 2020

Jane Lytvynenko · April 29, 2020

Peter Aldhous · Dec. 20, 2017

Peter Aldhous is a Science Reporter for BuzzFeed News and is based in San Francisco.

Peter Aldhous is a Science Reporter for BuzzFeed News and is based in San Francisco.