1709: The year that Europe froze solid

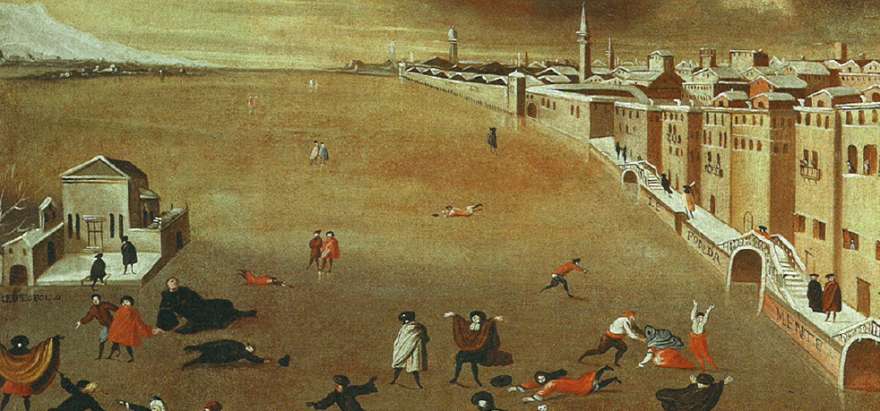

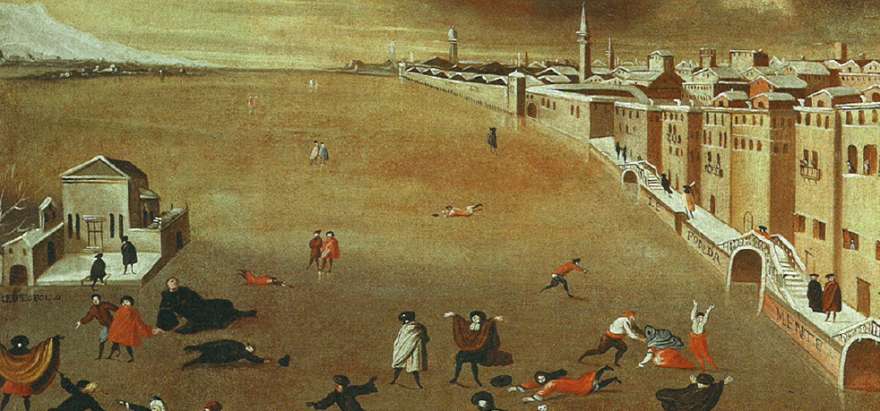

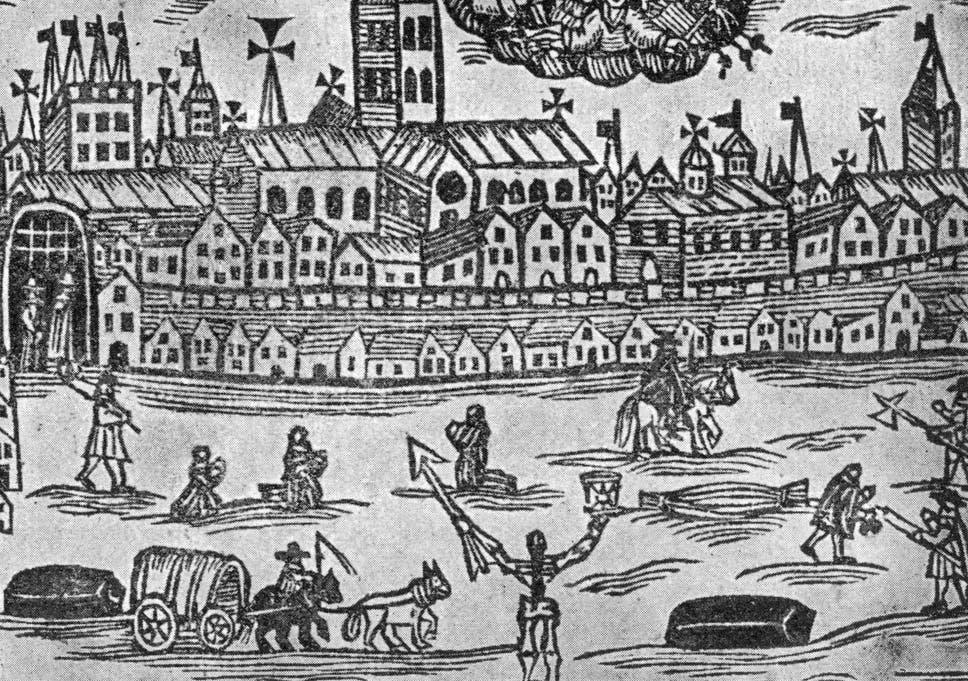

The Venetian lagoon frozen over in 1709.

Early January 1709 temperatures were dropping over most of Europe (Pain 2009). The cold remained for three weeks, and was followed by a brief thaw. Then temperatures plunged again and stayed there. From Scandinavia in the north to Italy in the south, lakes, rivers and even the sea froze. At Upminster, shortly north-east of London, temperature fell to -12oC on 10 January 1709, while it sank to -15oC in Paris on 14 January, and stayed at that level for the next 11 days. It has been estimated that the winter air temperature in Europe was as much as 7oC below the average for 20th century Europe. Not only was January very cold, it also turned out to be unusually stormy (Pain 2009).

In England the winter of 1709 became known as the Great Frost, while it in France entered the legend as Le Grand Hiver (Pain 2009). In France, even the king and his courtiers at the Palace of Versailles struggled to keep warm. In Scandinavia the Baltic froze so thoroughly that people could walk across the sea as late as April 1709. In Switzerland hungry wolves became a problem in villages. Venetians were able to skid across the frozen lagoon (see painting above).

According to a canon from Beaune in Burgundy, "travellers died in the countryside, livestock in the stables, wild animals in the woods; nearly all birds died, wine froze in barrels and public fires were lit to warm the poor". From all over the country came reports of people found frozen to death. Roads and rivers were blocked by snow and ice, and transport of supplies to the cities became difficult. Paris waited three months for fresh supplies (Pain 2009).

In Russia, the intense cold contributed significantly to the defeat of the Swedish army at Poltava under King Karl XII. Poltava became a political turning point for both Sweden and Russia: Sweden never regained its former military might, while Russia began to emerge as a European superpower (see text below).

Click here to jump back to the list of contents.

1709: Swedish defeat at Poltava UKRAINE

In 1697 the Swedish king Karl XII (1682-1718) assumed the crown at the age of fifteen, at the death of his father. As king, he embarked on a series of battles overseas. In 1700, Denmark-Norway, Saxony, and Russia united in an alliance against Sweden, using the perceived opportunity as Sweden was ruled by the young and inexperienced King. Early that year, all three countries declared war against Sweden. King Karl had to deal with these threats one by one, which he in a very determined way set out to do.

Having first defeated Denmark-Norway in 1700, King Karl turned his attention upon the two other powerful neighbours, Poland and Russia; lead by King August II and Tsar Peter the Great, respectively. First Russia was attacked. At the Narva Riverthe outnumbered Swedish army 20 November 1700 attacked the much larger Russian army under cover of a blizzard, divided the Russian army in two and won the battle. Next Karl next turned towards Poland and defeated King August and his allies at Kliszow in 1702. Then he turned back towards Russia, to finish Tsar Peter off for good.

In the meantime, Tsar Peter had embarked on a military reform plan to improve the quality of the Russian army. Especially the development of the artillery was emphasised. In the last days of 1707 King Karl crossed the frozen Weichsel River, and began advancing into Ukraine with his 77,400 man strong army. Already 28 January 1708 Karl together with an advanced group of 600 men crossed Njemen River and took the city Grodno. Shortly after this all hostilities were stopped, as both armies went into winter quarters.

The Russian tactical plan was to avoid a decisive battle before the Swedish army had been weakened by the progress of time. When hostilities were resumed in June 1708 the Russian army therefore slowly retreated towards Moscow, burning all villages to make the Swedish supply situation difficult. With great success this tactic would be used again 105 years later against the French invasion under Napoleon, and was in 1708 known as the Zjolkijevskij plan (Englund 1989). First Karl XII headed towards Moscow with his army, but it rapidly turned out being very difficult to supply the army in the deserted landscape. In addition, the summer 1708 was cold and wet, making life miserable for the Swedish soldiers. He therefore decided to turn south-east towards the more rich regions around the city Poltava. Before reaching Poltava the winter began, and the armies once again went into their winter quarters. The Swedish army went into winter quarters at the city Baturin, about 200 km NE of Kiev. The winter rapidly became very cold, not only in Russia, but in most of Europe, adding additional trouble to the already difficult Swedish supply situation. At the end of January 1709 the Swedish army resumed hostilities, but the winter soon made all operations virtually impossible. It became late April 1709 before Karl reached the city Poltava, 130 km SW of Kharkov.

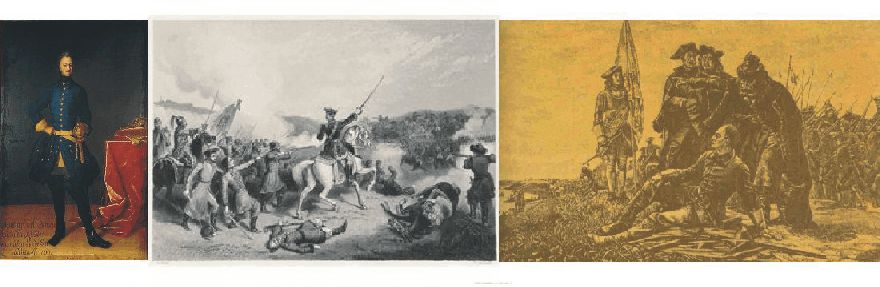

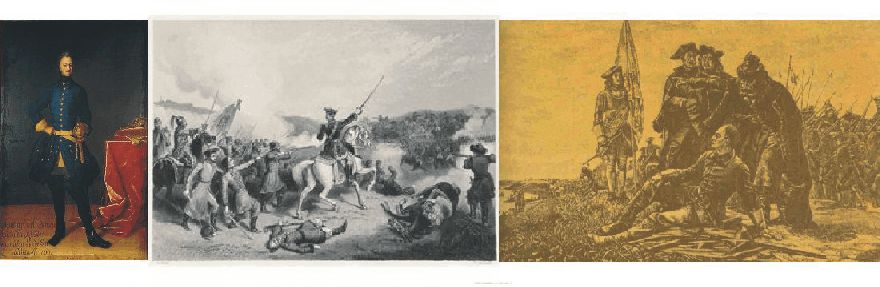

King Karl XII of Sweden (left). Battle of Poltava (centre). King Karl at the Dnieper River during the catastrophic retreat following the battle of Poltava.

The extremely low temperatures characterizing the winter 1708-1709 had taken their toll on the Swedish soldiers. When the Swedish army finally began its siege of Poltava 1 May 1709, Karl has lost most of his army without any big battles being fought. In June Tsar Peter began concentrating an army shortly north of Poltava. Karl had to face this treat, but following the hard winter he was only able to muster about 12,000 men for the attack. The attack was launched 28 June 1709, but was affected by some tactical confusion on the Swedish side. After some initial successes, the Swedish army was defeated thoroughly by the much larger Russian army, mainly due to its numerical superiority, and partly because of the now very strong and efficient Russian artillery. A catastrophic retreat followed to the Dnieper River, where what was left of the Swedish army had to surrender.By this, the battle at Poltava represented a climatic induced turning point for both Sweden and Russia. Sweden never regained its former military might, while Russia was beginning to emerge as a European superpower.

King Karl XII himself managed to escape with 1,200 Swedish survivors to the northerly province of the Ottoman Empire. Here he was held as a kind of prisoner until 1714, when he jumped onto a horse and escaped back to Sweden. He died 30 November 1718 during the siege of the Norwegian fortifications at Frederikssten. Some rumours claim that he was shot by a Swedish officer, but a more likely cause is that he simply did not take sufficient cover against fire from the Norwegian soldiers.

Click here to jump back to the list of contents.

NORTH AMERICA FREEZES

A brief history of epidemic and pestilential diseases; with the principal phenomena of the physical world, which precede and accompany them, and observations deduced from the facts stated. : In two volumes.

SECTION VII. Historical view of pestilential epidemics from the year 1701 to 1788.

THE year 1701 appears to have been excessively dry in America. Dr. Rush relates that during the dry summer of 1782, a rock in the Skuylkill appeared above the surface of the water, on which were engraven the figures 1701. How little do men suspect the value of this inscription! To this alone I am indebted for the fact of extreme drouth in that year—and the fact is among the proofs of an extraordinary evaporation, before dis|charges of fire and lava from volcanoes. In 1701 was an erup|tion of Vesuvius; in 1702 of Etna. It will hereafter appear that a similar dry season in 1782 preceded the great eruption of Heckla in 1783. Indeed it is a general fact, and as far as I can learn, such seasons seldom occur, except during the approach of comets, or antecedent to volcanic eruptions.

This was a pestilential period. In 1701 Toulon lost two thirds of its inhabitants by the plague, and the Levant was se|verely affected about the same time. See the bills of mortality for Augsburg, Dresden and Boston.

In 1702 appeared a comet; Etna discharged its fires, and in Boston raged a malignant small-pox, attended, in many cases, with a scarlet eruption, which was mistaken for the scarlet fever. It appears from Fairfield's diary that this disease appeared in June and was at first mild, not fatal to any of the patients. In August died one patient—in September it became very mortal, and in this month was attended with a "sort of fever called scarlet fever." In October, many died of the "fever and the small-pox, and it was a time of sore distress," on which account the general court sat at Cambridge.

Rodama: a blog of 18th century & Revolutionary French trivia

THURSDAY, 26 MAY 2016

The winter of 1709: letters of Liselotte

The correspondence of Louis XIV's sister-in-law, the Princess Palatine Elisabeth-Charlotte, duchess of Orléans (1652–1722), mother of the future Regent, is rightly prized for its down-to-earth comments and wealth of witty anecdote. Here is the "Great Winter" as it appears in her letters.

Curiously enough, the weather did not at first excite that much comment from "Liselotte". On 10th January 1709 she wrote to her half-sister, the Raugravine Amalia- Elisabeth without even mentioning the freezing temperature. On 17th January, she alluded to it only in passing: Last Sunday the cold was atrocious and we had to have a terrific fire lit in the room where we ate.

Her letter of 10th January to the Electress Sophia of Hanover, however, is more forthcoming:

The cold here is so fierce here that it fairly defies description. I am sitting by a roaring fire, have a screen before the door, which is closed, so that I can sit here with a sable fur piece around my neck and my feet in a bearskin sack, and I am still shivering with cold and can barely hold the pen. Never in my life have I seen a winter such as this one; the wine freezes in bottles.

READ THE REST HERE

The Venetian lagoon frozen over in 1709.

Early January 1709 temperatures were dropping over most of Europe (Pain 2009). The cold remained for three weeks, and was followed by a brief thaw. Then temperatures plunged again and stayed there. From Scandinavia in the north to Italy in the south, lakes, rivers and even the sea froze. At Upminster, shortly north-east of London, temperature fell to -12oC on 10 January 1709, while it sank to -15oC in Paris on 14 January, and stayed at that level for the next 11 days. It has been estimated that the winter air temperature in Europe was as much as 7oC below the average for 20th century Europe. Not only was January very cold, it also turned out to be unusually stormy (Pain 2009).

In England the winter of 1709 became known as the Great Frost, while it in France entered the legend as Le Grand Hiver (Pain 2009). In France, even the king and his courtiers at the Palace of Versailles struggled to keep warm. In Scandinavia the Baltic froze so thoroughly that people could walk across the sea as late as April 1709. In Switzerland hungry wolves became a problem in villages. Venetians were able to skid across the frozen lagoon (see painting above).

According to a canon from Beaune in Burgundy, "travellers died in the countryside, livestock in the stables, wild animals in the woods; nearly all birds died, wine froze in barrels and public fires were lit to warm the poor". From all over the country came reports of people found frozen to death. Roads and rivers were blocked by snow and ice, and transport of supplies to the cities became difficult. Paris waited three months for fresh supplies (Pain 2009).

In Russia, the intense cold contributed significantly to the defeat of the Swedish army at Poltava under King Karl XII. Poltava became a political turning point for both Sweden and Russia: Sweden never regained its former military might, while Russia began to emerge as a European superpower (see text below).

Click here to jump back to the list of contents.

1709: Swedish defeat at Poltava UKRAINE

In 1697 the Swedish king Karl XII (1682-1718) assumed the crown at the age of fifteen, at the death of his father. As king, he embarked on a series of battles overseas. In 1700, Denmark-Norway, Saxony, and Russia united in an alliance against Sweden, using the perceived opportunity as Sweden was ruled by the young and inexperienced King. Early that year, all three countries declared war against Sweden. King Karl had to deal with these threats one by one, which he in a very determined way set out to do.

Having first defeated Denmark-Norway in 1700, King Karl turned his attention upon the two other powerful neighbours, Poland and Russia; lead by King August II and Tsar Peter the Great, respectively. First Russia was attacked. At the Narva Riverthe outnumbered Swedish army 20 November 1700 attacked the much larger Russian army under cover of a blizzard, divided the Russian army in two and won the battle. Next Karl next turned towards Poland and defeated King August and his allies at Kliszow in 1702. Then he turned back towards Russia, to finish Tsar Peter off for good.

In the meantime, Tsar Peter had embarked on a military reform plan to improve the quality of the Russian army. Especially the development of the artillery was emphasised. In the last days of 1707 King Karl crossed the frozen Weichsel River, and began advancing into Ukraine with his 77,400 man strong army. Already 28 January 1708 Karl together with an advanced group of 600 men crossed Njemen River and took the city Grodno. Shortly after this all hostilities were stopped, as both armies went into winter quarters.

The Russian tactical plan was to avoid a decisive battle before the Swedish army had been weakened by the progress of time. When hostilities were resumed in June 1708 the Russian army therefore slowly retreated towards Moscow, burning all villages to make the Swedish supply situation difficult. With great success this tactic would be used again 105 years later against the French invasion under Napoleon, and was in 1708 known as the Zjolkijevskij plan (Englund 1989). First Karl XII headed towards Moscow with his army, but it rapidly turned out being very difficult to supply the army in the deserted landscape. In addition, the summer 1708 was cold and wet, making life miserable for the Swedish soldiers. He therefore decided to turn south-east towards the more rich regions around the city Poltava. Before reaching Poltava the winter began, and the armies once again went into their winter quarters. The Swedish army went into winter quarters at the city Baturin, about 200 km NE of Kiev. The winter rapidly became very cold, not only in Russia, but in most of Europe, adding additional trouble to the already difficult Swedish supply situation. At the end of January 1709 the Swedish army resumed hostilities, but the winter soon made all operations virtually impossible. It became late April 1709 before Karl reached the city Poltava, 130 km SW of Kharkov.

King Karl XII of Sweden (left). Battle of Poltava (centre). King Karl at the Dnieper River during the catastrophic retreat following the battle of Poltava.

The extremely low temperatures characterizing the winter 1708-1709 had taken their toll on the Swedish soldiers. When the Swedish army finally began its siege of Poltava 1 May 1709, Karl has lost most of his army without any big battles being fought. In June Tsar Peter began concentrating an army shortly north of Poltava. Karl had to face this treat, but following the hard winter he was only able to muster about 12,000 men for the attack. The attack was launched 28 June 1709, but was affected by some tactical confusion on the Swedish side. After some initial successes, the Swedish army was defeated thoroughly by the much larger Russian army, mainly due to its numerical superiority, and partly because of the now very strong and efficient Russian artillery. A catastrophic retreat followed to the Dnieper River, where what was left of the Swedish army had to surrender.By this, the battle at Poltava represented a climatic induced turning point for both Sweden and Russia. Sweden never regained its former military might, while Russia was beginning to emerge as a European superpower.

King Karl XII himself managed to escape with 1,200 Swedish survivors to the northerly province of the Ottoman Empire. Here he was held as a kind of prisoner until 1714, when he jumped onto a horse and escaped back to Sweden. He died 30 November 1718 during the siege of the Norwegian fortifications at Frederikssten. Some rumours claim that he was shot by a Swedish officer, but a more likely cause is that he simply did not take sufficient cover against fire from the Norwegian soldiers.

Click here to jump back to the list of contents.

NORTH AMERICA FREEZES

A brief history of epidemic and pestilential diseases; with the principal phenomena of the physical world, which precede and accompany them, and observations deduced from the facts stated. : In two volumes.

Webster, Noah, 1758-1843.

SECTION VII. Historical view of pestilential epidemics from the year 1701 to 1788.

THE year 1701 appears to have been excessively dry in America. Dr. Rush relates that during the dry summer of 1782, a rock in the Skuylkill appeared above the surface of the water, on which were engraven the figures 1701. How little do men suspect the value of this inscription! To this alone I am indebted for the fact of extreme drouth in that year—and the fact is among the proofs of an extraordinary evaporation, before dis|charges of fire and lava from volcanoes. In 1701 was an erup|tion of Vesuvius; in 1702 of Etna. It will hereafter appear that a similar dry season in 1782 preceded the great eruption of Heckla in 1783. Indeed it is a general fact, and as far as I can learn, such seasons seldom occur, except during the approach of comets, or antecedent to volcanic eruptions.

This was a pestilential period. In 1701 Toulon lost two thirds of its inhabitants by the plague, and the Levant was se|verely affected about the same time. See the bills of mortality for Augsburg, Dresden and Boston.

In 1702 appeared a comet; Etna discharged its fires, and in Boston raged a malignant small-pox, attended, in many cases, with a scarlet eruption, which was mistaken for the scarlet fever. It appears from Fairfield's diary that this disease appeared in June and was at first mild, not fatal to any of the patients. In August died one patient—in September it became very mortal, and in this month was attended with a "sort of fever called scarlet fever." In October, many died of the "fever and the small-pox, and it was a time of sore distress," on which account the general court sat at Cambridge.

Rodama: a blog of 18th century & Revolutionary French trivia

THURSDAY, 26 MAY 2016

The winter of 1709: letters of Liselotte

The correspondence of Louis XIV's sister-in-law, the Princess Palatine Elisabeth-Charlotte, duchess of Orléans (1652–1722), mother of the future Regent, is rightly prized for its down-to-earth comments and wealth of witty anecdote. Here is the "Great Winter" as it appears in her letters.

Curiously enough, the weather did not at first excite that much comment from "Liselotte". On 10th January 1709 she wrote to her half-sister, the Raugravine Amalia- Elisabeth without even mentioning the freezing temperature. On 17th January, she alluded to it only in passing: Last Sunday the cold was atrocious and we had to have a terrific fire lit in the room where we ate.

Her letter of 10th January to the Electress Sophia of Hanover, however, is more forthcoming:

The cold here is so fierce here that it fairly defies description. I am sitting by a roaring fire, have a screen before the door, which is closed, so that I can sit here with a sable fur piece around my neck and my feet in a bearskin sack, and I am still shivering with cold and can barely hold the pen. Never in my life have I seen a winter such as this one; the wine freezes in bottles.

READ THE REST HERE

John Locher/AP

John Locher/AP