Failure to Prosecute UK War Crimes in Iraq Exposes ICC's Own Failings

The court could have set a powerful precedent in holding Britain to account. Instead, it has become a laughing stock and few will be able to take it seriously again.

A platoon sergeant of the 1st Royal Regiment of Fusiliers guards members

of 39 Engineer Squadron 32 Armoured Engineers as they breach one of

the first obstacles clearing the way for British troops to enter Iraq on

March 21, 2003. (Photo: Cpl. Paul (Jabba) Jarvis/British MoD/Flickr/cc)

"A court finds UK war crimes but will not take action." That was the extraordinary BBC News headline last week following the International Criminal Court's publication of its detailed investigation into war crimes committed by British troops during the occupation of Iraq.

The ICC's report is based on the findings of a preliminary inquiry to determine both whether there is a reasonable basis to believe that war crimes were committed and to assess whether the UK has itself investigated and sought to prosecute those accused of involvement.

The British government has gone to exceptional lengths to ensure that British troops accused of committing war crimes in Iraq are immune from prosecution.

The ICC concluded that because the UK was "not unwilling" to investigate and prosecute its soldiers for committing war crimes in Iraq, the investigation was being closed.

The truth, however, is that the British government has gone to exceptional lengths to ensure that British troops accused of committing war crimes in Iraq are immune from prosecution. Out of the hundreds of cases pending against British soldiers, by June this year only one such case remained open.

In March, the government presented the Overseas Operations (Service Personnel and Veterans) Bill. The law will place a five-year limit on criminal prosecutions against soldiers accused of war crimes and a six-year limit on civil actions.

Any cases outside of these periods will require the attorney general's consent. There will also be a duty for the government to consider abandoning its commitment to the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) ahead of military expeditions overseas.

The new law will stop countless claims of war crimes against British soldiers who served as part of the military occupation of Iraq. The bill had its third reading in the Commons in November and is primed to becoming law in the new year.

The aim of the proposed law is to protect British soldiers from what the government calls "vexatious litigation."

The case of Phil Shiner

The government often cites the case of Phil Shiner, the British lawyer who successfully exposed the role of British soldiers in the torture and murder of Baha Mousa, an Iraqi man who died in British custody in Basra in 2003.

Shiner was struck off by the Solicitors Regulation Authority in 2017 after being found guilty of professional misconduct charges including paying an Iraqi middleman to find claimants to make allegations against British soldiers.

Shiner had submitted thousands of claims against the British army so this was the opportunity the government - having previously denounced law firms involved in litigation against British soldiers as "ambulance-chasing lawyers"—was waiting for. In the same year, the government shut down its own investigation, the Iraq Historic Allegations Team (IHAT), which had been set up to investigate allegations of torture by British soldiers. None of the IHAT cases led to prosecutions.

Despite denying the allegations of war crimes, the government reached out-of-court settlements with at least 326 claimants. It was, however, following on from Shiner's work that the ICC picked up the baton where the IHAT had dropped it. According to a report by the BBC and the Sunday Times, British IHAT detectives said they had seen evidence of war crimes carried out by British soldiers and alleged that Shiner's case was used to close down their investigation.

Stark contrast

The ICC said that there was a reasonable basis to believe that between 2003 and 2009 British soldiers murdered at least seven prisoners and tortured 54 others. It found there was a reasonable basis to believe that at least seven captives were raped or sexually abused as detainees in Camp Breadbasket run by British armed forces.

The stark contrast between the ICC's findings and its actions are deeply troubling. It is essentially saying that we know you raped and murdered but you're free to go—because we believe you'll police yourself.

This is what one IHAT detective said: "The Ministry of Defence had no intention of prosecuting any soldier of whatever rank he was unless it was absolutely necessary, and they couldn't wriggle their way out of it."

Why was the British Army in Iraq and Afghanistan?

The UK sent forces to Afghanistan as part of the international coalition that invaded the country in 2001 following the 9/11 al-Qaeda attacks in the US, and to Iraq in 2003 as part of a US-led invasion to overthrow Saddam Hussein.

In both countries British soldiers became increasingly bogged down fighting against insurgents opposed to international occupation.

In Iraq, British forces were handed responsibility for security in Basra and three provinces in the south, but their presence was challenged by Muqtada al-Sadr's Mahdi army militia fighters.

In September 2007, British forces withdrew from their bases in the city to the airport on the outskirts, the targets of "relentless attacks," according to an International Crisis Group report which said that their retreat was viewed by locals as an "ignominious defeat."

In Afghanistan, British forces had been deployed in 2006 to Helmand Province. But they proved ineffective against the resurgent Taliban and in 2009 more than 100 British soldiers were killed.

British troops eventually withdrew from Afghanistan in 2014, with 454 service personnel killed over the course of their 13-year campaign in the country.

Around 120,000 British troops served in Iraq for six years. In light of all that has emerged with US atrocities in Abu Ghraib and Camp Bucca, and revelations of the atrocities and coverups unearthed by WikiLeaks, it is not inconceivable that British troops committed many war crimes or that the British government would seek to cover them up.

After all, these soldiers were part of and allied to the most powerful and organised military machine in the world. They were armed, trained and motivated to fight, capture, interrogate and kill in the name of Queen and country.

Of course, it wasn't just Iraq. The brutality had begun in Afghanistan following the US-led invasion in 2001. A BBC Panorama investigation this year found a deliberate "policy of execution-style killings was being carried out by [British] Special Forces" against unarmed men.

Panorama also uncovered communications from Afghan Army officials who refused to go out on patrol with British soldiers because of their penchant for murder and their tendency to blame their Afghan counterparts in order to avoid investigation. They also said British soldiers planted drugs and guns on the bodies of unarmed Afghans they had killed.

Once again, the government was left to investigate itself. Operation Northmoor was set up in 2014 but the investigation was closed down in 2017 after looking at 675 allegations of abuse, but without interviewing key Afghan witnesses. The investigating Royal Military Police (RMP) "found no evidence of criminal behaviour by the armed forces in Afghanistan."

In November, the Australian Defence Force (ADF) released findings from a four-year inquiry that found Australian soldiers serving in Afghanistan, "fuelled by bloodlust" and "competition killing," tortured and executed unarmed Afghan prisoners and then covered up their crimes by planting guns. Thirty-nine people were killed. Some of them were shot dead. Two children reportedly had their throats slit.

The report includes the chilling account of one special forces operative and how ADF troops idolised British and American soldiers' atrocities: "Whatever we do, though, I can tell you the Brits and the US are far, far worse. I've watched our young guys stand by and hero worship what they were doing, salivating at how the US were torturing people."

Although, at times, it has backed ICC prosecutions of individuals, the Trump administration has shown its open hostility to the court by freezing ICC assets and placing prosecutor Fatou Bensouda and others on a travel ban.

A paper tiger

The ICC is also being penalised by the US for investigating Israeli war crimes. It is now hoped that President-elect Biden will reverse the sanctions but it won't be an easy rise for the ICC either way.

It is now hoped that President-elect Biden will reverse the sanctions but it won't be an easy rise for the ICC either way.

It could have achieved something meaningful with Britain but once again it seems the ICC is quite willing to prosecute Africans but far less able to prosecute powerful Western nations.

It may be because Britain is, by the government's own account, one of the largest contributors to ICC coffers that this prosecution didn't go ahead. Or it may be that the ICC is just a paper tiger. Whatever the case, there is no escaping the connotations of this.

The ICC could have set a very powerful and visible precedent in holding Britain to account. It could have given hope and a semblance of justice to those who have neither. Instead, the ICC is a laughing stock and few will be able to take it seriously again.

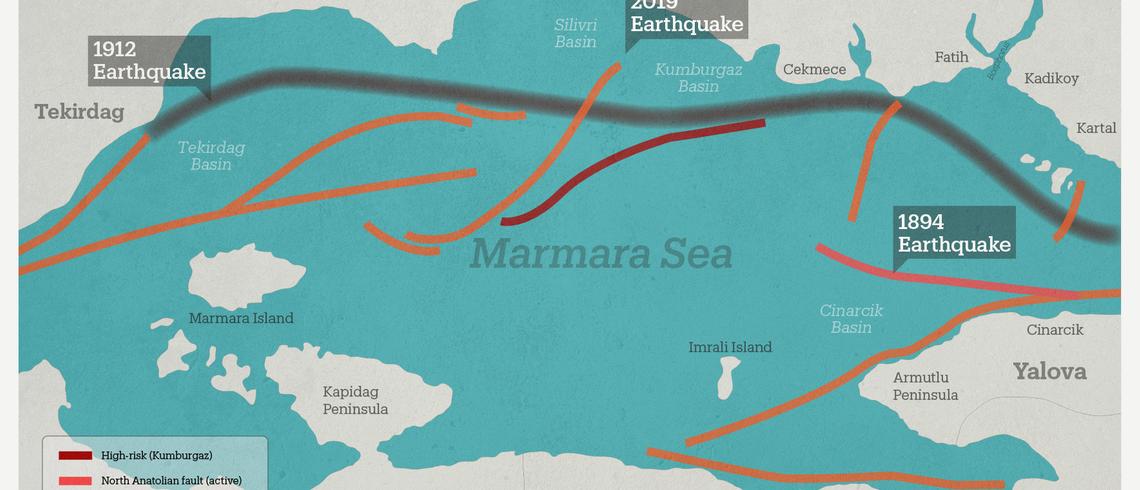

(Samet Catak/Enes Danis / TRTWorld)

(Samet Catak/Enes Danis / TRTWorld)