Caltech Researchers Read a Jellyfish’s Mind

The human brain has 100 billion neurons, making 100 trillion connections. Understanding the precise circuits of brain cells that orchestrate all of our day-to-day behaviors—such as moving our limbs, responding to fear and other emotions, and so on—is an incredibly complex puzzle for neuroscientists. But now, fundamental questions about the neuroscience of behavior may be answered through a new and much simpler model organism: tiny jellyfish.

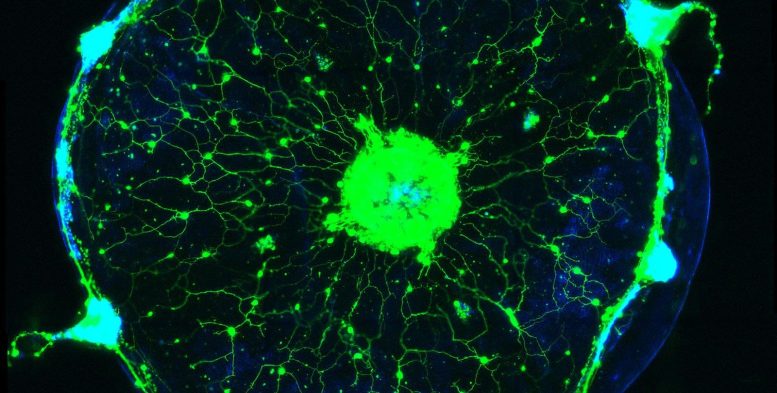

With a new genetic toolbox, researchers can view jellyfish neurons as they light up in real time. Jellyfish do not have a centralized brain; rather, their brain cells (neurons) are distributed in a diffuse net throughout the body. As shown in this video, this study discovered that there is actually spatial organization to the way that neurons are activated when the animal is coordinating behavior. Credit: B. Weissbourd

Caltech researchers have now developed a kind of genetic toolbox tailored for tinkering with Clytia hemisphaerica, a type of jellyfish about 1 centimeter in diameter when fully grown. Using this toolkit, the tiny creatures have been genetically modified so that their neurons individually glow with fluorescent light when activated. Because a jellyfish is transparent, researchers can then watch the glow of the animal’s neural activity as it behaves naturally. In other words, the team can read a jellyfish’s mind as it feeds, swims, evades predators, and more, in order to understand how the animal’s relatively simple brain coordinates its behaviors.

A paper describing the new study appears in the journal Cell on November 24, 2021. The research was conducted primarily in the laboratory of David J. Anderson, Seymour Benzer Professor of Biology, Tianqiao and Chrissy Chen Institute for Neuroscience Leadership Chair, Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator, and director of the Tianqiao and Chrissy Chen Institute for Neuroscience.

When it comes to model organisms used in laboratories, jellyfish are an extreme outlier. Worms, flies, fish, and mice—some of the most commonly used laboratory model organisms—are all more closely related, genetically speaking, to one another than any are to a jellyfish. In fact, worms are evolutionarily closer to humans than they are to jellyfish.

“Jellyfish are an important point of comparison because they’re so distantly related,” says Brady Weissbourd, postdoctoral scholar and first author on the study. “They let us ask questions like, are there principles of neuroscience shared across all nervous systems? Or, what might the first nervous systems have looked like? By exploring nature more broadly, we may also discover useful biological innovations. Importantly, many jellyfish are small and transparent, which makes them exciting platforms for systems neuroscience. That is because there are amazing new tools for imaging and manipulating neural activity using light, and you can put an entire living jellyfish under a microscope and have access to the whole nervous system at once.”

A jellyfish folds the right side of its body to bring a tiny brine shrimp to its mouth. Credit: B. Weissbourd

Rather than being centralized in one part of the body like our own brains, the jellyfish brain is diffused across the animal’s entire body like a net. The various body parts of a jellyfish can operate seemingly autonomously, without centralized control; for example, a jellyfish mouth removed surgically can carry on “eating” even without the rest of the animal’s body.

This decentralized body plan seems to be a highly successful evolutionary strategy, as jellyfish have persisted throughout the animal kingdom for hundreds of millions of years. But how does the decentralized jellyfish nervous system coordinate and orchestrate behaviors?

After developing the genetic tools to work with Clytia, the researchers first examined the neural circuits underlying the animal’s feeding behaviors. When Clytia snags a brine shrimp in a tentacle, it folds its body in order to bring the tentacle to its mouth and bends its mouth toward the tentacle simultaneously. The team aimed to answer: How does the jellyfish brain, apparently unstructured and radially symmetric, coordinate this directional folding of the jellyfish body?

By examining the glowing chain reactions occurring in the animals’ neurons as they ate, the team determined that a subnetwork of neurons that produces a particular neuropeptide (a molecule produced by neurons) is responsible for the spatially localized inward folding of the body. Additionally, though the network of jellyfish neurons originally seemed diffuse and unstructured, the researchers found a surprising degree of organization that only became visible with their fluorescent system.

“Our experiments revealed that the seemingly diffuse network of neurons that underlies the circular jellyfish umbrella is actually subdivided into patches of active neurons, organized in wedges like slices of a pizza,” explains Anderson. “When a jellyfish snags a brine shrimp with a tentacle, the neurons in the ‘pizza slice’ nearest to that tentacle would first activate, which in turn caused that part of the umbrella to fold inward, bringing the shrimp to the mouth. Importantly, this level of neural organization is completely invisible if you look at the anatomy of a jellyfish, even with a microscope. You have to be able to visualize the active neurons in order to see it—which is what we can do with our new system.”

Weissbourd emphasizes that this is only scratching the surface of understanding the full repertoire of jellyfish behaviors. “In future work, we’d like to use this jellyfish as a tractable platform to understand precisely how behavior is generated by whole neural systems,” he says. “In the context of food passing, understanding how the tentacles, umbrella, and mouth all coordinate with each other lets us get at more general problems of the function of modularity within nervous systems and how such modules coordinate with each other. The ultimate goal is not only to understand the jellyfish nervous system but to use it as a springboard to understand more complex systems in the future.”

The new model system is straightforward for researchers anywhere to use. Jellyfish lineages can be maintained in artificial sea water in a lab environment and shipped to collaborators who are interested in answering questions using the little animals.

Reference: “A genetically tractable jellyfish model for systems and evolutionary neuroscience” by Brandon Weissbourd, Tsuyoshi Momose, Aditya Nair, Ann Kennedy, Bridgett Hunt and David J. Anderson, 24 November 2021, Cell.

DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.10.021

In addition to Weissbourd and Anderson, additional co-authors are Tsuyoshi Momose of Sorbonne Université in France, graduate student Aditya Nair, former postdoctoral scholar Ann Kennedy (now an assistant professor at Northwestern University), and former research technician Bridgett Hunt. Funding was provided by the Caltech Center for Evolutionary Science, the Whitman Center of the Marine Biological Laboratory, the Life Sciences Research Foundation, and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

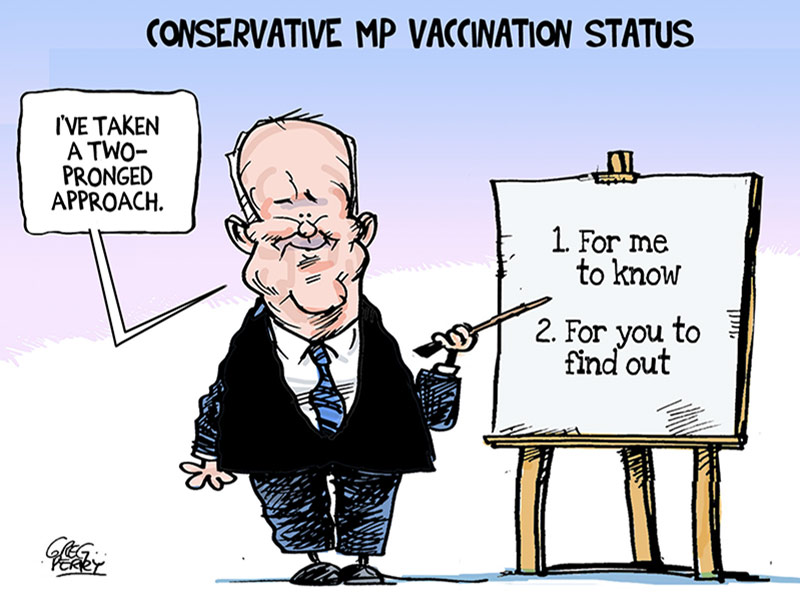

Cartoon by Greg Perry.

Cartoon by Greg Perry.