Despite Covid hospitalizations trending downward, 80% of hospitals across the country are under ‘high or extreme stress’

Eric Berger

Fri 4 Feb 2022

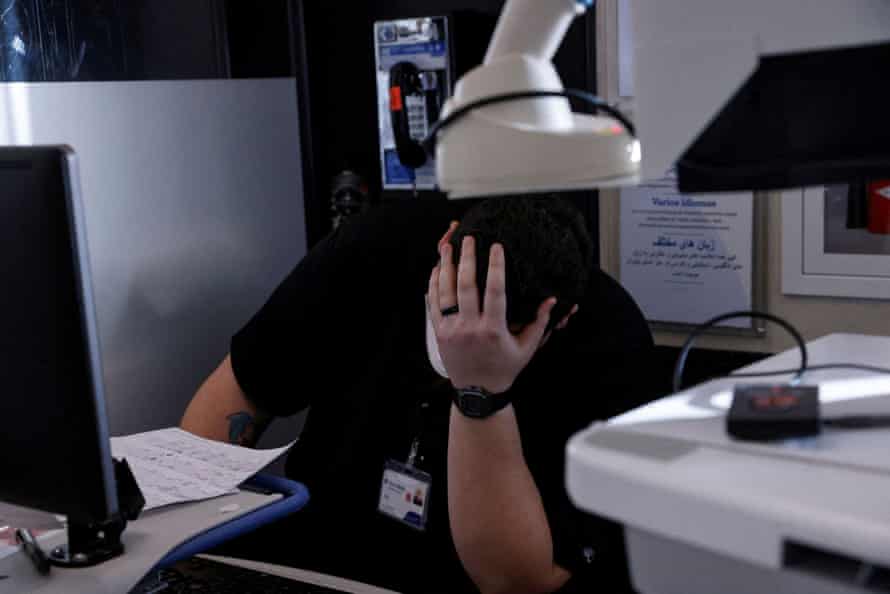

Dr Brian Resler, an emergency physician in the San Francisco Bay Area, recently polled a group of doctors on an overnight shift about their jobs.

“Everyone of us said if we could go back, we would choose a different career,” said Resler, who spoke on the condition that the Guardian does not identify his hospital.

Hospitals in half of US states close to capacity as Omicron continues surge

Resler and his fellow doctors feel that way although California has recently seen a sharp decrease in the number of Covid-19 cases after the spike due to the highly contagious Omicron variant. That slump in cases has largely been mirrored across the US as the Omicron wave has peaked and many parts of the US are firmly on its downslope.

But, while some health experts have predicted that the worst of the pandemic is behind us, the ripple effects of the virus, such as its impact on patients needing care for other issues, continue to test the limits of the US healthcare system and its providers.

“Most people got into healthcare because they wanted to help people and make a difference, and I think at this point, it’s just broken beyond repair,” said Resler, 36, who has worked in emergency medicine for seven years.

Across the country, the daily average of Covid-19 cases and daily average of hospitalizations due to the virus has decreased by 49% and 16% respectively over the past two weeks, according to New York Times data.

Despite those positive trends, 80% of US hospitals in the last week of January were under “high or extreme stress”, meaning that more than 10% of their hospitalizations were due to Covid-19, according to data compiled by National Public Radio using a framework from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington.

California was the tenth worst in the country with 69% of hospitals under extreme stress, meaning that more than 20% of those facilities’ hospitalizations were due to Covid-19.

“Even though the odds of getting very sick with Omicron and the odds of getting sick once you are vaccinated and boosted are lower, the sheer number of infections means that there are still going to be a lot of sick people,” said Resler, who explained that most of the Covid-19 patients who were hospitalized were unvaccinated.

Also, because of the threat of the virus, many people earlier in the pandemic were afraid or unable to seek care for their health issues. Now that delay is catching up with patients, Resler said.

“That leads to a lot of overwhelming of the system and a lot of angry patients. A lot of patients hear that things are overwhelmed, but when faced with long wait times and an overwhelmed emergency department, it’s a lot different to see it for yourself when you are sick and seeking care than hearing about it,” he said.

In Missouri, 79% of the hospitals are under extreme stress, which is the second highest percentage in the country. At Mercy hospital in Springfield, in the south-western part of the state, about 28% of their hospitalizations are Covid-19 patients, according to Erik Frederick, the hospital’s chief administrative office.

Even if patients were admitted for other reasons but happened to test positive for Covid-19, “those patients require the same amount of resources, as far as isolation and all the personal protective equipment and human resources,” said Frederick.

The high transmissibility of the Omicron variant means that the hospitals also have a significant number of staff who test positive for the virus and must then quarantine. This creates an increased patient load for the providers that are left, and hospitals must offer incentives to encourage staff to pick up additional shifts and hire nurses from outside agencies, Frederick said.

“It creates a lot of stress on the healthcare system,” Frederick said.

Children’s hospitals have also not been immune from the strain caused by the Omicron variant. Over two weeks in January, there was a 20% increase in the cumulative number of child Covid-19 cases, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Every few hours at University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, the house supervisor, who coordinates care for patients, sends out alerts about the numbers of available beds in particular units.

“When those numbers get small, it means that we have to make some hard decisions,” said Dr Rachel Pearson, assistant professor of pediatrics and the medical humanities at UT Health San Antonio. “Sometimes that means kids who I would prefer to be upstairs with my hospital pediatrics team are stranded in the [emergency department].”

Sometimes the hospital has to stop accepting transfer patients from smaller hospitals or clinics or had to have those patients wait in the emergency department.

“We are stretched. It seems like we have been able to find creative solutions to safely care for kids for the most part, but I really feel for those rural doctors out there because I know sometimes they are on the phone and making call, after call, after call, trying to find a hospital with a higher level of care that can accept their sick patient,” said Pearson.

Still, Pearson is encouraged that the Food and Drug Administration could soon authorize the Pfizer vaccine against Covid-19 for children under five.

And Frederick, who also sees patients from rural areas with low vaccination rates, said he is optimistic about the future of the pandemic.

“I’m optimistic about the numbers, but most of my optimism comes from my team and how they have responded and continue to respond,” he said.

Resler isn’t so optmistic. His early interest in emergency medicine came from the rewarding nature of providing care to patients, some of whom don’t initially have a heartbeat. Now he and colleagues talk about the “thank you” to “[expletive] you,” ratio, and the former is consistently outweighed by the latter, he said.

“I spend most of my day apologizing and being yelled at,” said Resler. “We had similar issues years ago, but it’s just gotten much worse, to the point where anytime I go see a new patient, it’s a pleasant surprise when they are not angry at me.”

This article was updated on 4 February 2022 to clarify that Missouri has the second highest percentage of hospitals under ‘extreme stress’, according to NPR data.