Book Review: Authoritarian Contagion: The Global Threat to Democracy by Luke Cooper

In Authoritarian Contagion: The Global Threat to Democracy, Luke Cooper explores the rise of ‘authoritarian protectionism’ across the globe. This book is an excellent introduction to authoritarian politics and will prove highly informative for readers wanting to strengthen their understanding of contemporary events, writes D. Kaan Akcay.

Authoritarian Contagion: The Global Threat to Democracy. Luke Cooper. Bristol University Press. 2021.

The Rubicon has been crossed for liberal democracies around the globe. Human history, already plagued by authoritarian governments and movements, faces another wave of authoritarianism with a splash of ethno-nationalism. With his extensive knowledge and scholarship on Europe, Luke Cooper defines this new iteration as ‘authoritarian protectionism’ in his latest book, Authoritarian Contagion.

‘Authoritarian protectionism’ is a novel political concept that rehashes some authoritarian characteristics of old. Cases like Turkey have already experienced deep levels of democratic backsliding, while the US shows early signs of decay through the tenure of President Donald Trump. Hegemonic politics, where political and economic gains can only be earned at the expense of others, reflects the idea of a zero-sum game, as observed in the 2021 Capitol insurrection. ‘Real’ Americans devastate the democratic process for their own gain. Cooper positions this mindset as the belief that ‘the world will end for others but not us’ (6): a powerful idea that acts like a ‘contagion’.

To explain this phenomenon, Cooper explores the historical process of authoritarian politics, with special regard to the authoritarian individualism of former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and former US President Ronald Reagan. Cooper argues against the idea of a post-politics period where the neoliberal mode of operation and democratic systems are the convergence points of human civilisation, proposed by Francis Fukuyama’s The End of History among other works. Cooper claims that events such as 9/11, the 2008 recession and now COVID-19 show that this is not the case. Protectionism and the narrative of a corrupt elite are being normalised through anti-globalisation sentiments and ‘America first’ rhetoric.

Authoritarian Contagion suggests that once this school of far-right authoritarian thought is normalised, gaining a foothold in mainstream politics, it is hard to dislodge (12). Furthermore, the political movements and parties that combine nations’ historical experiences with this new politics are proving especially transformative through such normalisation (21). This new protectionist agenda thrives on the idea that the collective is of importance, rather than the individual. Fighting for Christianity, fighting for America, getting ‘the man’s job’ done: these are all elements that define the authoritarian protectionism of Trump and many others. There are heteronormative, ethno-nationalistic and militaristic masses living in an alternative reality (30).

Photo by Samantha Sophia on Unsplash

For Cooper’s conception, these factors, combined with a sense of immediate crisis, are the basis of the new wave of authoritarianism that the book explores in detail. It can be said that ‘authoritarian protectionism’ captures the convergence of populism and racism. Although underemphasised in the book, elements of the ‘us versus them’ rhetoric and references to a corrupt global elite and taking back the power for ‘ordinary people’ are all well-established aspects of populist movements. Today, proposed by Cooper as diverging from previous examples, there is a layer of racism on top (43).

Authoritarian Contagion explains the context of nationalism and authoritarianism adequately to give the reader all the necessary information, effectively showing the rise of the far right in combination with authoritarian politics and hybrid regimes, which are in between full democracies and full authoritarianism on the spectrum of political systems. As Cooper suggests, these are not necessarily new phenomena, but they threaten the future of democracies. Furthermore, while democracies seem to be the dominant system across the globe, especially in the West, liberal democracy is fairly new. Universal suffrage and civil rights were lacking in most of the old democracies up until the 1960s. Cooper clearly illustrates the need to fight and protect the formal and substantive aspects of democracy, arguing that there is no perfect setting in which democracy thrives without problems (68).

The greatest strength of Cooper’s work is his competence in capturing all the aspects, concepts and developments of authoritarian politics applicable to different cases. Protectionism can be observed in Hungary, Poland, Turkey, the US, China, France, the UK and beyond. All these states have suffered from repeated attacks on the liberal qualities of democracies.

As Cooper suggests, authoritarian protectionism also damages inclusive global efforts to solve many of the biggest problems humanity is facing, including global warming, pandemics and energy crises. In the last chapter, ‘Authoritarian Futures?’, Cooper explores how politics shapes the relationship between nature and humans. The mercantile nature of protectionism prevents cooperation between states. Only their people and nation will survive, in lieu of others. The climate crisis, income inequality and other global concerns become a tool that fuels authoritarian policies that fail to offer any solutions (133). Many issues, including climate change, require a global effort, yet there can be no collective action in a zero-sum game.

The main weakness of the work comes from overlooked details in the analysed cases. In the chapter ‘Sino-America’, we read a comparative analysis of authoritarian protectionism in China and the US. The bleak outlook on China’s assimilation policies towards minorities, especially the Uyghurs, presents a strong case of ethno-nationalism; comparable evidence for the US is lacking. While the book presents a variety of voter data, it is difficult to isolate the causes of the success of Trump without further evidence, leaving much to be desired regarding possible takeaways. While comparisons can provide some general findings about the state of the world, examining vastly different polities may be unhelpful for the purposes of the book. In sum, the lack of detail in the analyses impedes the aim of understanding ‘authoritarian contagion’ in greater depth.

The notion that ‘the Rubicon has been crossed’, proposed by Cooper in the opening of the book, is one that I strongly agree with. Democratic backsliding and the rise of this new iteration of authoritarian politics are not new phenomena. Yet, in line with the book’s premise, they are spreading in a highly contagious manner. Having lived in a country ahead of this curve, I found the book to be an excellent introduction to authoritarian politics with an emphasis on contemporary ethno-nationalistic protectionism. It is a great research primer for all scholars in the field, and an informative work for curious readers who want to strengthen their understanding of contemporary events with robust knowledge.

- This review first appeared at LSE Review of Books.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3dnV4V1

About the reviewer

D. Kaan Akcay – Bilkent University

D. Kaan Akcay is an MA student in Political Science at Bilkent University. He is interested in the fields of political economy and comparative politics. His research currently focuses on the relationship between populism and democracy, and economic policy with an emphasis on the effects of international priorities of states.

The Rubicon has been crossed for liberal democracies around the globe. Human history, already plagued by authoritarian governments and movements, faces another wave of authoritarianism with a splash of ethno-nationalism. With his extensive knowledge and scholarship on Europe, Luke Cooper defines this new iteration as ‘authoritarian protectionism’ in his latest book,

The Rubicon has been crossed for liberal democracies around the globe. Human history, already plagued by authoritarian governments and movements, faces another wave of authoritarianism with a splash of ethno-nationalism. With his extensive knowledge and scholarship on Europe, Luke Cooper defines this new iteration as ‘authoritarian protectionism’ in his latest book,

In recent years, catastrophic wildfires, as evidenced by viral video clips depicting burning forests, billowing smoke and evacuees, have sparked growing public concern around the globe. What are the causes and consequences of this environmental crisis and what can be done to prevent it? These are the main subjects addressed in Eve Darian-Smith’s

In recent years, catastrophic wildfires, as evidenced by viral video clips depicting burning forests, billowing smoke and evacuees, have sparked growing public concern around the globe. What are the causes and consequences of this environmental crisis and what can be done to prevent it? These are the main subjects addressed in Eve Darian-Smith’s

Joseph E. Uscinski – University of Miami

Joseph E. Uscinski – University of Miami

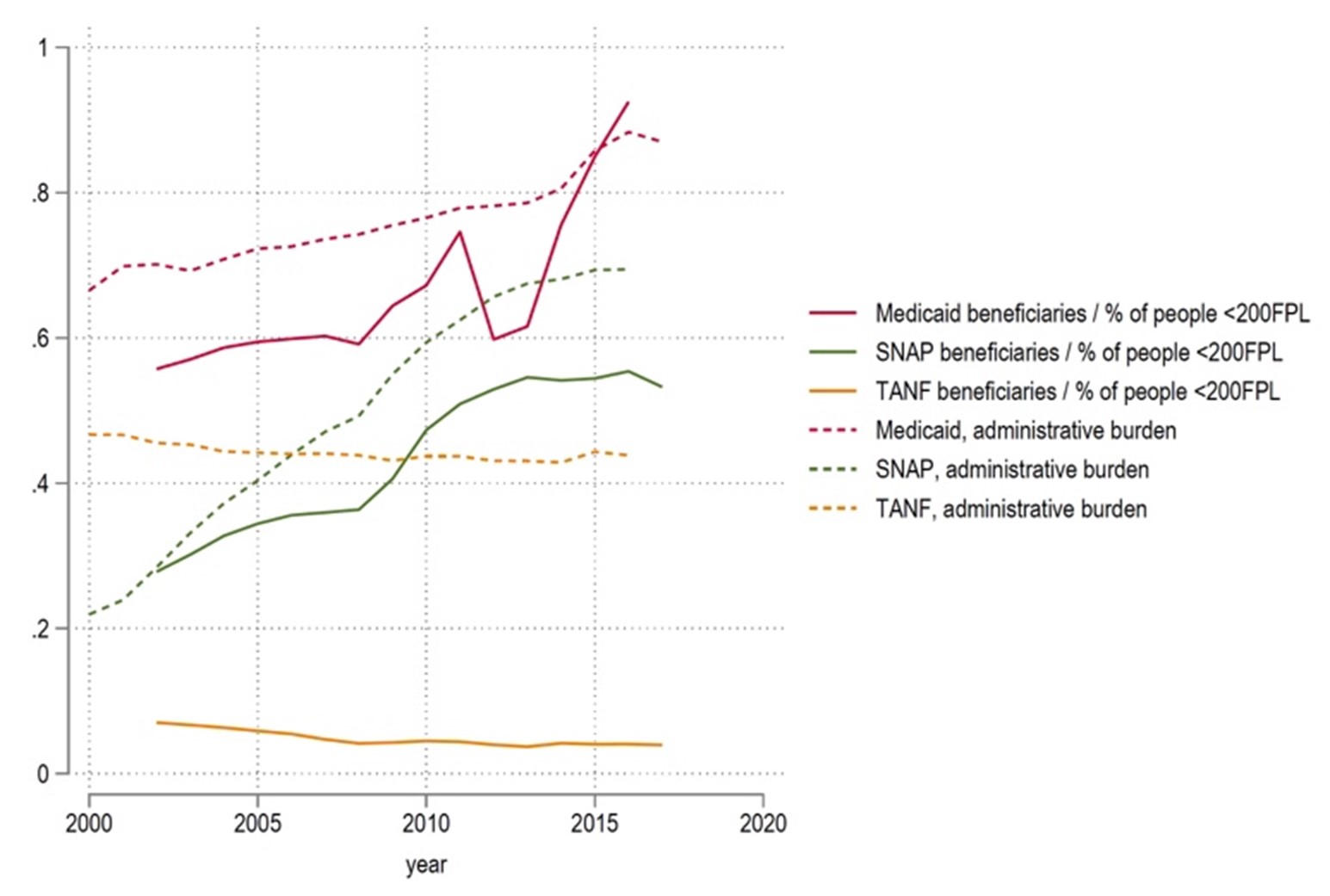

Ashley M. Fox – Rockefeller College of Public Affairs and Policy

Ashley M. Fox – Rockefeller College of Public Affairs and Policy Wenhui Feng – Tufts University

Wenhui Feng – Tufts University Megan M. Reynolds – University of Utah

Megan M. Reynolds – University of Utah