Venezuela: Opposing the blockade is our main task

The United States is waging an economic war against Venezuela.

The US has imposed sanctions that attempt to prevent governments and companies from having any dealings with Venezuelan government bodies, such as the state-owned oil company PDVSA, unless granted an exemption that is only given with conditions that are very unfavourable to Venezuela. Non-US companies can be targeted with secondary sanctions if they defy US orders.

The sanctions amount to an economic blockade. They aim to prevent Venezuela's government from participating in trade with the outside world. The goal is to cause an economic crisis leading to the overthrow of the Venezuelan government.

Sanctions began in March 2015 when US president Barack Obama declared Venezuela an “unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security and foreign policy of the United States”.1 The severity of the restrictions intensified under US president Donald Trump.

The US and its allies have seized about $60 billion in Venezuelan assets, including the US subsidiary of the Venezuelan national oil company, CITGO. The Venezuelan government can not pay its dues to the United Nations because US banks have confiscated Venezuela's money.

Impact of the blockade

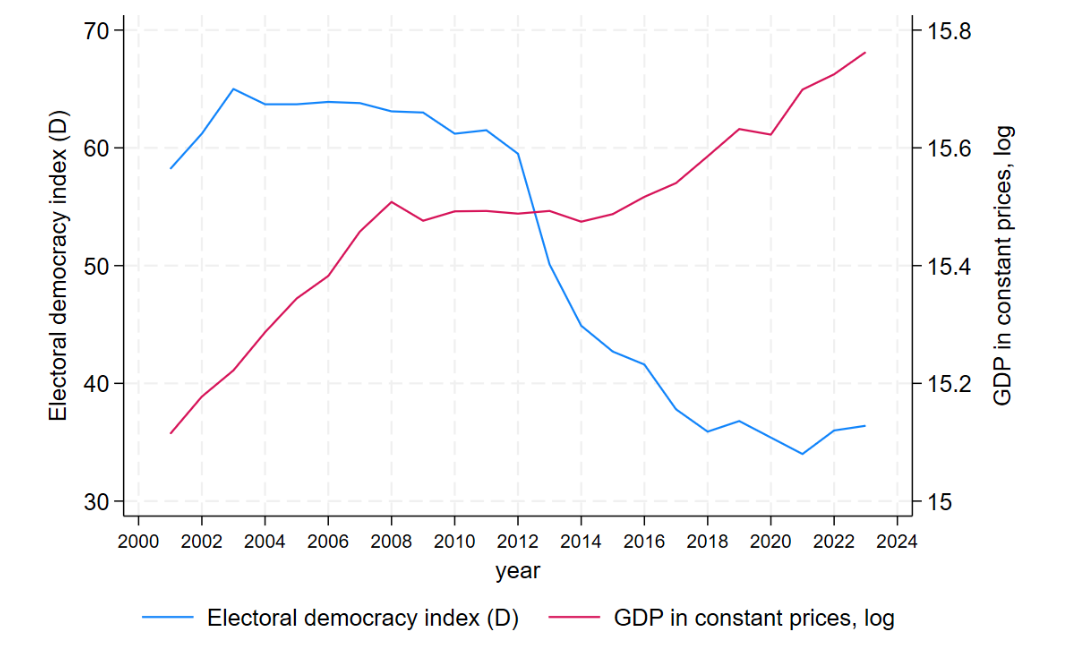

The blockade has severely damaged the Venezuelan economy. The oil industry is unable to get spare parts for machinery. This has reduced Venezuela's oil production and revenue. Similarly, electricity and water supply have been affected by sanctions.

The blockade has caused severe hardship to the people. There are shortages of medicines, vaccines and medical equipment. The sanctions have caused an increase in the death rate. Jeffrey Sachs and Mark Weisbrot estimated that there were more than 40,000 excess deaths during the years 2017-18.2

Despite the blockade, Venezuela has made progress in some areas. The house building program begun by former president Hugo Chavez continues, and has now built 5 million social housing units. People in many areas have organised themselves into communes, with the support of the government.

Nevertheless, the blockade has caused an economic crisis and a lot of suffering. Venezuela’s human development index, which improved greatly under Chavez, declined dramatically after the imposition of the blockade.

Attempts to circumvent blockade

The Venezuelan government tries to circumvent the sanctions by using private companies as intermediaries. Of course, the intermediaries expect to make a profit on such deals. The sanctions have enriched a section of the capitalist class.

Some government functions have been effectively privatised. In addition, secrecy surrounding the government’s attempts to circumvent the blockade creates increased opportunities for corruption. The blockade is largely responsible for the rise of corruption.

Impact of the blockade on election results

The US hopes that by creating hardship, the blockade will lead to growing discontent, which will undermine support for the government: some people may blame the government for the country's problems; others may come to believe that the US is too powerful to be successfully defied.

In the recent presidential election, Venezuelan voters faced a difficult choice. If they voted for Nicolas Maduro, the blockade would continue. If they voted for Edmundo Gonzalez, the candidate favoured by the US, the blockade would be lifted.

This blackmail was partially successful. According to the results announced by the National Electoral Council (CNE), Maduro won, but with a fairly narrow majority. Maduro got 52% of votes cast, while the extreme right candidate Gonzalez got 43%. Other opposition candidates got a combined 5%.

There was a 42% abstention rate. This means Maduro got the votes of about 30% of eligible voters, while Gonzalez got 25%.

For comparison, in the 2013 presidential election Maduro got 51% of the vote with an 80% turnout, meaning he obtained the votes of 41% of eligible voters.3 The rise in abstention may indicate that some people had become discouraged by the difficulties of life under the blockade, or that they were critical of both the government and the opposition.

However, the government still has enough support to organise big rallies throughout the country — larger than those of the opposition.4 An important section of the population refuses to be intimidated by the US economic war.

Tasks of socialists

The main task of socialists in the US and its allies such as Australia is to campaign against the blockade. However, some recent articles in LINKS International Journal of Socialist Renewal have had a different emphasis.5 They condemn the Maduro government as a dictatorship and accuse it of electoral fraud. They also describe its economic policies as neoliberal.

There are some good reasons for criticising the Maduro government. It has carried out some undemocratic actions — for example, depriving the Communist Party of Venezuela of its electoral registration.

In a society under siege, it is not surprising that the government becomes more repressive. We should criticise the repression, but we must also campaign to end the siege.

It is understandable that many Venezuelan leftists criticise the government’s economic policies. Wages are very low, while some people are very rich, including the capitalists who help the government circumvent the blockade.

Some government policies ease the hardship to a certain extent. Certain basic services, such as electricity and public transport, are cheap or free. People receive food parcels from the government. But workers are still understandably dissatisfied.

We can criticise how the government responds to the blockade. But we should acknowledge the reasons for the policies adopted — in particular, the attempt to circumvent the blockade, which involves working with capitalists and making concessions to them.

Andreina Chavez Alava, a writer for Venezuelanalysis.com, is critical of the Maduro government, but condemns attempts by the US government and the Venezuelan extreme right to overthrow it. She says:

A lot of people like me are not entirely happy with the government’s liberal overtures in the name of circumventing the US blockade that moves away from the socialist alternative. We have felt ignored when making criticisms or requesting information regarding salaries, socioeconomic data, and the real state of healthcare, education and the electrical system and what investment is going (if any) into them.

We don’t want to surrender our country to the US, but we also need guarantees about the next six years if Maduro wins. Will the government continue trapped in its echo chamber? Will they weed out the opportunists and corrupt? Will the socialist project be revitalized?

No matter what goes down on July 28, only the Venezuelan people can save themselves and guarantee real democracy on the ground and hope for the future.6

While criticising the Maduro government, Chavez Alava supported Maduro's re-election. She explained that the right-wing opposition supports extreme neoliberal policies and would make Venezuela a “US client state”, whereas the Maduro government stands for “sovereignty” and the “construction of socialism” (however imperfect it may be in pursuing the latter goal).7 She places great importance on the building of communes, with government support.

Activists in Venezuela have every right to criticise government policy. But for socialists in the imperialist countries, our priorities should be different. We should put the main blame for Venezuela’s problems on US imperialism, and campaign to end the blockade.

Accusation of election fraud

Some leftists claim that the election results published by the CNE are false. This claim is based on the CNE's failure to publish results broken down by polling stations. Critics assume that fraud is the only possible explanation, but other explanations are possible. For example, it may be because the government, while winning the nationwide vote, is embarrassed by the loss of support in some traditional Chavista areas.

The results reported by the CNE seem plausible, given the large attendance at pro-Maduro rallies. The proportion voting for Maduro according to the CNE is similar to that reported by opinion polling company Hinterlaces (55.6% in an opinion survey in June, compared to 52% reported by the CNE in the election on July 28).8

The US is using the accusation of electoral fraud as an excuse for continuing and intensifying the blockade. This makes it very important for us not to make unproven allegations.

The extreme right is planning to “inaugurate” Gonzalez as “president” in January 2025, as they did with Juan Guaido in 2019. We should denounce this plan. We should also denounce the use of the blockade as a form of blackmail to influence the election results.

- 1

US executive order: FACT SHEET: Venezuela Executive Order | whitehouse.gov (archives.gov)

- 2

Jeffrey Sachs and Mark Weisbrot: Collective Punishment: The Case of Venezuela - Center for Economic and Policy Research (cepr.net)

- 3

Arnold August: Voting Trends: Do They Favor Machado/González or Maduro? - Venezuelanalysis

- 4

Venezuela: Candidates Hold Final Campaign Rallies Ahead of Presidential Vote - Venezuelanalysis

- 5

See for example: Venezuela after the presidential election: ‘This is not a left-wing government’ | Links;Against authoritarianism and neoliberalism in Venezuela: A view from the critical left | Links

- 6

Andreina Chavez Alava: The Scam Behind 'Free Elections' - Venezuelanalysis

- 7

Andreina Chavez Alava: What Is at Stake for the Venezuelan Elections? - Venezuelanalysis

- 8

Voting intentions in June, according to Hinterlaces: Hinterlaces on X: "PRESIDENCIALES 2024 ¿ Por quién votará usted ? #MonitorPais Hinterlaces (Junio 2024) Hinterlaces ¡ Nadie Sabe Más ! https://t.co/cA9vg1Wjln" / X