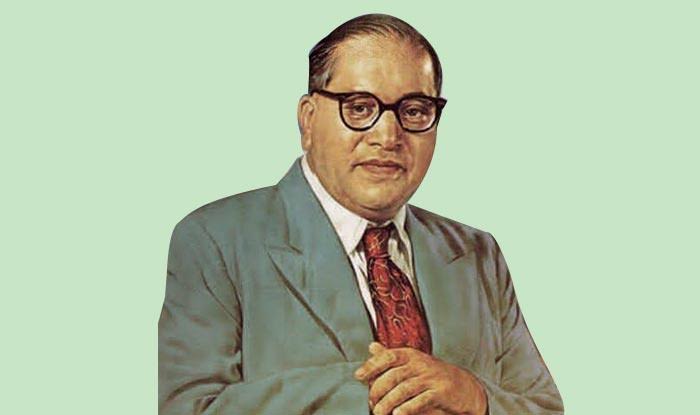

The scholarship of Bhimrao Ambedkar (1891-1956) has become visible during the last couple of years, but the discussion of his conceptual contribution and his relevance to contemporary political theory appears underdeveloped. Ambedkar was a scholar on caste, democracy and law; and he has been celebrated as the chairperson of the drafting committee of India’s constitution. Some comprehensive studies of Ambedkar’s political thought have recently emerged (see, for example, Kumar, 2015), and there are several other new publications on this topic. However, the focus on the fact that Ambedkar was a student of the American philosopher John Dewey remains celebrated to the point of representing a theoretical stalemate. The fact that Ambedkar studied under Dewey during his time as a student at Columbia University has been an important point in literature on Ambedkar and his movement since Eleanor Zelliot’s seminal study (2001). But this point may also end up blurring our understanding of Ambedkar’s theoretical contribution and his relevance in contemporary political theory.

The recurring inclination to highlight that Ambedkar was a student of Dewey has both advantages and disadvantages. The advantage is that one could learn about the intellectual history and one of Ambedkar’s main sources of inspiration. Yet the disadvantage is that existing trends in political thought is confirmed at the expense of realising the potential and scope of a radical political philosophy. This is why Ambedkar’s thoughts and concepts should be made more explicit.

As argued in Berg (2020) Ambedkar’s concepts can be brought in fruitful dialogue with the approach to hegemony of the late Argentinian philosopher Ernesto Laclau (2014). The political theorist Oliver Marchart characterises Laclau’s conceptual contributions as one of the main achievements in contemporary social and political thought (Marchart, 2018). But Ambedkar’s concepts, distinctions and thoughts do offer clear-cut contributions to such radical political theory developments as well. Laclau’s key concept in his approach to hegemony is antagonism by which he means that one pole dominates and breaks down the strength and power of the other pole (Laclau, 2014). His concept of antagonism differs from an ordinary and Marxist understanding of conflict. According to Marchart, it represents Laclau’s idea about political ontology. Ambedkar’s discussion of ‘touchables’ and ‘untouchables’ in the context of a system of ‘graded inequality’ can be effectively explained via Laclau’s approach in critical political theory. In fact, while Ambedkar’s concept of graded inequality could be viewed as a concept that explains the frequent atrocities and everyday forms of humiliation in the caste system, it also represents Ambedkar’s independent theoretical contribution.

Ambedkar was a thinker with a sustained interest in explaining and addressing caste-based oppression. His contribution to social and political theory should therefore bring into focus how he is engaging with an object of study that cannot be fully grasped through simply extending the application of Dewey’s concepts. Caste is a significant object of study, and Ambedkar’s conceptual innovation appeared bolstered by having addressed its multidimensionality.

One central task is nonetheless to delineate and specify how one could make sense of Ambedkar’s relationship to Dewey’s philosophy. It is clear that Dewey is a source of inspiration when reading Ambedkar’s most revolutionary text, Annihilation of Caste from 1936 (Ambedkar, 1989). Several scholars have described the relevance of Dewey and the American legacy (see, in particular, Zelliot, 2001). Recently, academic philosophers have followed up this relationship by introducing several insightful publications about Ambedkar and Dewey (Maitra, 2012; Mukherjee, 2009). Indeed, it has been valuable to have the American philosopher and Dewey-scholar Scott Stroud to engage with this topic. Stroud demonstrates how Ambedkar draws on Dewey’s texts in Annihilation of Caste. He also characterises Ambedkar as an Indian pragmatist (Stroud, 2016, 2017a, 2017b). However, while Stroud has presented several insightful observations, it would be inadequate to characterise Ambedkar as an Indian pragmatist. Nor would this label communicate the relevance that cultural context has for individual thinkers. Instead, one needs to follow up Keya Maitra’s suggestion (2012: 302) that Ambedkar’s personal experiences matter for his thinking, notably by focussing on his conceptual development and contribution.

Stroud argues that Ambedkar’s interpretation and use of Dewey’s concept of democracy can be understood as reconstruction in Dewey’s sense (Stroud 2017a). ‘Reconstruction’ is a key concept in Dewey’s Democracy and Education (Dewey, 1985). In one of its main applications, it concerns a reorganisation and development of received practices and institutions in order to enhance social cooperation and individual learning (Dewey, 1985: 82-86, 107). Ambedkar’s Buddhist conversion could be understood as a reconstruction in Dewey’s sense. However, even though this term has been used in the part of the literature on Ambedkar dealing with his Buddhist conversion (Jondhale and Beltz, 2004), we argue that Ambedkar’s understanding of democracy cannot be made sense of in terms of a reconstruction. This point becomes clearer by examining how Ambedkar engages with Dewey’s Democracy and Education.

In Annihilation of Caste, Ambedkar explores Dewey’s conception of democracy in Democracy and Education. Dewey’s conception of democracy is wide. For both Dewey and Ambedkar, democracy is defined as ‘primarily a mode of associated living, of conjoint communicated experience’ (Ambedkar 1989: 57). Ambedkar follows Dewey’s idea about how democracy represents an ideal for the organisation of society. Yet Dewey considers social conditions for the applicability of this ideal that differ from the conditions under which Ambedkar applies the same ideal. Dewey thinks that a modern society consists in constellation of loosely connected and overlapping groups, such as professional, religious, artistic, or political groups, or immigrant groups distinguished along ethnic lines (Dewey, 1985: 87-88). He thus takes social membership to consist in multiple memberships in various groups. Dewey does consider segregation based in race and class. Yet, in other cases, he observes, ‘many interests consciously communicated and shared; and there are varied and free points of contact with other modes of association’ (Dewey, 1985: 89). Dewey qualifies such cases as states of ‘social endosmosis’ (Dewey, 1985: 90). Identifying such states is crucial. He argues that in order to develop an ideal of democracy, one has to base it upon ‘societies which actually exist’ (Dewey, 1985: 88). Hence, in Dewey’s pragmatist approach, one first needs to ‘extract the desirable traits of forms of community life which actually exist and employ them to criticize undesirable features and suggest improvement’ (Dewey, 1985: 88-89). This qualifies Dewey’s conception of democracy as a socially immanent ideal (Good, 2006; Midtgarden, 2011, 2012).

Ambedkar adopts Dewey’s idea that democracy is characterised by ‘social endosmosis’ (1989: 57), but he redefines the discussion of democracy when examining different social conditions. Caste contradicts the kind of inter-group contact and sharing of interests across groups that democracy as an immanent ideal would entail. Additionally, the caste system legitimises social segregation in ways he fails to find in other cultural contexts. In other words, the social conditions for articulating and applying Dewey’s concept of democracy are radically different from those described in Democracy and Education. On Ambedkar’s account, the democratic ideal cannot be taken as socially immanent in the Hindu social order. This suggests that Ambedkar’s understanding and use of the concept of democracy cannot be seen as a reconstruction in Dewey’s sense as argued by Stroud (2017a). Instead, we think that Ambedkar’s use of concepts involves a far more radical approach.

According to the intellectual historian Quentin Skinner (2002: 67), the exegetical literature in the history of philosophy would often find coherence between philosophers at the expense of understanding how each philosopher writes to address particular questions in one’s society. This also applies to Ambedkar’s text Annihilation of Caste. Ambedkar wrote this essay in the mid-1930s, which is around the time that he had claimed that he would abandon Hinduism as a religion because of the oppression and atrocities that he and his people experienced. This claim has caused well-known controversies, which includes the objections by M. K. Gandhi. However, the text has greater theoretical substance. It is argued by Berg (2020) that Ambedkar in Annihilation of Caste develops an account of what can be characterised as an ontological drive of caste or the ‘grip of caste’. The revolutionary text suggests the ways in which Ambedkar was engaged with an intellectual project of analysing caste and going beyond it. It is in the process of thinking and addressing questions of caste-based oppression that he develops several innovative sociological concepts (Herrenschmidt, 2004). Therefore, we suggest that Ambedkar’s philosophy and concept development should be made more explicit. In doing so, one may bring an innovative thinker into dialogue with global political thought and strengthen the ontological turn in political theory (Laclau, 2014; Marchart, 2018) if one also brings in caste as his object of study.

About the authors

Dag-Erik Berg, Associate Professor of Political Science, Molde University College. Berg teaches political theory and globalisation and is the author of “Dynamics of Caste and Law” (Cambridge, 2020). He tweets at @DagErikBerg

Torjus Midtgarden, Professor of Philosophy, University of Bergen, Norway. Midtgarden has specialised on American pragmatism and has written extensively on the philosophy of John Dewey.

References

Ambedkar BR (1989) Annihilation of Caste. In: Moon V (ed.) Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Writings and Speeches: Bombay: Education Department, Government of Maharashtra, pp. 23–96.

Berg D-E (2020) Dynamics of Caste and Law: Dalits, Oppression and Constitutional Democracy in India. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dewey J (1985) Democracy and Education. Vol. 9. In: Boydston JA (ed.) The Middle Works of John Dewey, 1899-1924: Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

Good JA (2006) A search for unity in diversity: The “permanent Hegelian deposit” in the philosophy of John Dewey. Lanham MD: Lexington Books.

Herrenschmidt O (2004) Ambedkar and the Hindu Social Order. In: Jondhale S and Beltz J (eds) Reconstructing the World. B. R. Ambedkar and Buddhism in India: New Delhi: Oxford University Press, pp. 37–48.

Jaffrelot C (2005) Dr Ambedkar and untouchability: analysing and fighting caste. London: Hurst.

Jondhale S and Beltz J (eds) (2004) Reconstructing the world: B.R. Ambedkar and Buddhism in India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Kumar A (2015) Radical Equality: Ambedkar, Gandhi, and the Risk of Democracy. Stanford California: Stanford University Press.

Laclau E (2014) The rhetorical foundations of society. London: Verso.

Maitra K (2012) Ambedkar and the Constitution of India: A Deweyan Experiment. Contemporary Pragmatism 9(2): 301–320.

Marchart O (2018) Thinking antagonism: Political ontology after Laclau. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Midtgarden T (2011) The Hegelian Legacy in Dewey’s Social and Political Philosophy, 1915––1920. Transactions of the Charles S. Peirce Society 47(4): 361–388.

Midtgarden T (2012) Critical Pragmatism: Dewey’s social philosophy revisited. European Journal of Social Theory 15(4): 505–521.

Mukherjee AP (2009) B. R. Ambedkar, John Dewey, and the Meaning of Democracy. New Literary History 40(2): 345–370.

Skinner Q (2002) Visions of politics: regarding method, Vol. 1. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

Stroud SR (2016) Pragmatism and the Pursuit of Social Justice in India: Bhimrao Ambedkar and the Rhetoric of Religious Reorientation. Rhetoric Society Quarterly 46(1): 5–27.

Stroud SR (2017a) What Did Bhimrao Ambedkar Learn from John Dewey’s Democracy and Education? The Pluralist 12(2): 78–103.

Stroud SR (2017b) The like-mindedness of Dewey and Ambedkar. Forward Press, 19 May.

Zelliot E (2001) From untouchable to Dalit: essays on the Ambedkar Movement. New Delhi: Manohar Publishers.

Democratic Anarchy will Build the Best Life Possible

Why on Earth a Country of Laws and Borders?

Reconciling Mutual Aid With Revolutionary Violence: The Case of Peter Kropotkin

Human Potential: The Case of Peter Kropotkin

Propaganda By Deed And The Glory Of Self-Sacrifice: The Case of Peter Kropotkin