An international group of archaeologists have discovered a missing piece in the story of human evolution.

Excavations at the Israeli site of Nesher Ramla have recovered a skull that may represent a late-surviving example of a distinct Homo population, which lived in and around modern-day Israel from about 420,000 to 120,000 years ago

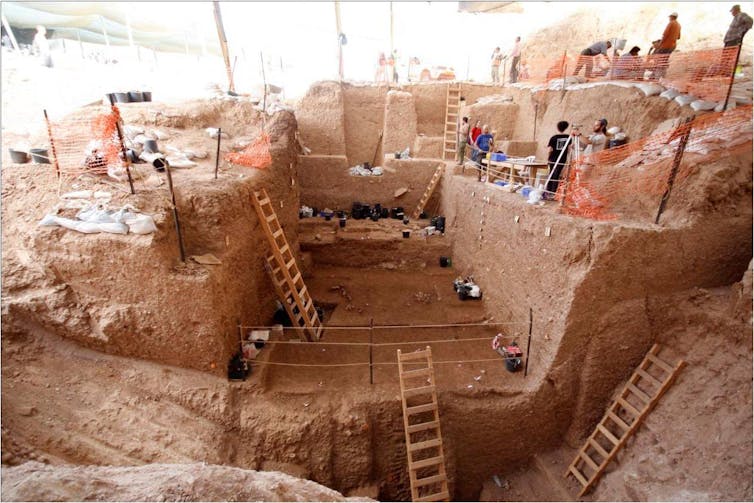

Aerial view of the Nesher Ramla sinkhole. The site of Nesher Ramla during excavation. Yossi Zaidner

As researchers Israel Hershkovitz, Yossi Zaidner and colleagues detail in two companion studies published today in Science, this archaic human community traded both their culture and genes with nearby Homo sapiens groups for many thousands of years.

The new fossils

Pieces of a skull, including a right parietal (towards the back/side of the skull) and an almost complete mandible (jaw) were dated to 140,000–120,000 years old, with analysis finding the person it belonged to wasn’t fully H. sapiens.

The Nesher Ramla mandible and skull. Avi Levin and Ilan Theiler, Sackler / Tel Aviv University

Nor were they Neanderthal, however, which was the only other type of human thought to have been living in the region at the time.

Instead, this individual falls right smack in the middle: a unique population of Homo never before recognised by science

Imaging of the Nesher Ramla mandible and teeth. Ariel Pokhojaev/Tel Aviv University

Through detailed comparison with many other fossil human skulls, the researchers found the parietal bone featured “archaic” traits that are substantially different from both early and recent H. sapiens. In addition, the bone is considerably thicker than those found in both Neanderthals and most early H. sapiens.

The jaw too displays archaic features, but also includes forms commonly seen in Neanderthals.

The bones together reveal a unique combination of archaic and Neanderthal features, distinct from both early H. sapiens and later Neanderthals.

The authors suggest fossils found at other Israeli sites, including the famous Lady of Tabun, might also be part of this new human population, in contrast to their previous Neanderthal or H. sapiens identification.

The “Lady of Tabun” (known to archaeologists as Tabun C1) was discovered in 1932 by pioneering archaeologist Yusra and her field director, Dorothy Garrod.

Extensively studied, this important specimen taught us much about Neanderthal anatomy and behaviour in a time when very little was known about our enigmatic evolutionary cousins.

Read more: Ancient teenager the first known person with parents of two different species

If Tabun C1 and others from the Qesem and Zuttiyeh Caves were indeed members of the Nasher Ramel Homo group, this reanalysis would explain some inconsistencies in their anatomy previously noted by researchers.

The mysterious Nesher Ramla Homo may even represent our most recent common ancestor with Neanderthals. Its mix of traits supports genetic evidence that early gene flow between H. sapiens and Neanderthals occurred between 400,000 and 200,000 years ago. In other words, that interbreeding between the different Homo populations was more common than previously thought.

Even more puzzling, the team also found a collection of some 6,000 stone tools at the Nesher Ramla site.

A flint scraper — one of the stone tools of Nesher Ramla Homo. Tal Rogovski

These tools were made the same way contemporaneous H. sapiens groups made their technology, with the similarity so strong it appears the two populations — Nesher Ramla Homo and H. sapiens — were hanging out on a regular basis. It seems they weren’t just exchanging genes, but also tips on tool-making.

And there was fire!

The site also produced bones of animals caught, butchered, and eaten on-site. These findings indicate Nesher Ramla Homo hunted a range of species, including tortoise, gazelle, aurochs, boar and ostrich.

Furthermore, they were using fire to cook their meals, evident through the uncovering of a campfire feature the same age as the fossils. Indeed, the Nesher Ramla Homo were not only collecting wood to make campfires and cook, but were also actively managing their fires as people do today.

Exposure of animal bones and lithic artifacts in the layer with the Nesher Ramla Homo fossils. Yossi Zaidner

While the earliest indications of controlled use of fire is much older — perhaps one million years ago - the interesting thing about this particular campfire is the evidence that Nesher Ramla people tended to it as carefully as contemporary H. sapiens and Neanderthals did their own fires.

Most impressive is that the campfire feature survived, intact, outside of a protected cave environment for so long. It is now the oldest intact campfire ever found in the open air.

In sum, if we think of the story of human evolution like an Ikea bookcase that isn’t quite coming together, this discovery is effectively like finding the missing shelf buried at the bottom of the box. The new Nesher Ramla Homo allows for a better-fitting structure, although a few mysterious “extra” pieces remain to be pondered over.

For example, exactly how did the different Homo groups interact with each other? And what does it mean for the cultural and biological changes that were occurring for Homo populations in this period?

Continuing to work with these questions (the “extra pieces”) will help us build a better understanding of our human past.

View of the deep section during excavation at Nesher Ramla, showing the deep. archaeological sequence. Yossi Zaidner

Senior Research Fellow, Griffith University

Disclosure statement

Dr Michelle Langley is a Senior Research Fellow in the Australian Research Centre for Human Evolution and Lecturer in Archaeology in the School of Environment and Science at Griffith University. She receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

New fossils reveal previously unknown population of archaic hominin from the Levant

In two companion studies, researchers reveal a previously unknown population of archaic hominin- the "Nesher Ramla Homo" - from a recently excavated site in Israel dated to roughly 140,000 to 120,000 years ago. Analysis of both the fossils and associated artifacts from the site suggests that the group represents a last surviving population of Middle Pleistocene Homo, characterized by a distinctive combination of Neanderthal and archaic human features and technology that until only recently was linked to more modern Homo lineages. It's been assumed that Neanderthals originated and thrived on the European continent well before the arrival of modern humans. However, recent evidence suggests a genetic contribution from a yet unknown non-European group, indicating a long and dynamic history of interaction between Eurasian and African hominin populations. Here, Israel Hershkovitz, Yossi Zaidner and colleagues present fossil, artifact, and radiometric evidence from the Levant region of the Middle East that illustrates this complexity. According to Hershkovitz et al., the newly discovered Nesher Ramla Homo exhibits anatomical features that are more archaic than contemporaneous Eurasian Neanderthals and the modern humans who also lived in the Levant. The findings indicate that this archaic lineage may represent one of the last surviving populations of Middle Pleistocene Homo in southwest Asia, Africa and Europe. In the companion study, Zaidner et al. provide the archaeological context of the new fossils, reporting on the associated radiometric ages, artifact assemblages and the behavioral and environmental insights they offer. Zaidner et al. show that the Nesher Ramla Homo were well versed in technologies that were previously only known among H. sapiens and Neanderthals. Together, the findings provide archaeological support for close cultural interactions and genetic admixture between different human lineages before 120,000 years ago. This may help explain the variable expression of the dental and skeletal features of later Levantine fossils. "The interpretation of the Nesher Ramla fossils and stone tools will meet with different reactions among paleoanthropologists. Notwithstanding, the age of the Nesher Ramla material, the mismatched morphological and archaeological affinities, and the location of the site at the crossroads of Africa and Eurasia make this a major discovery," writes Marta Lahr in an accompanying Perspective.

###

In two companion studies, researchers reveal a previously unknown population of archaic hominin- the "Nesher Ramla Homo" - from a recently excavated site in Israel dated to roughly 140,000 to 120,000 years ago. Analysis of both the fossils and associated artifacts from the site suggests that the group represents a last surviving population of Middle Pleistocene Homo, characterized by a distinctive combination of Neanderthal and archaic human features and technology that until only recently was linked to more modern Homo lineages. It's been assumed that Neanderthals originated and thrived on the European continent well before the arrival of modern humans. However, recent evidence suggests a genetic contribution from a yet unknown non-European group, indicating a long and dynamic history of interaction between Eurasian and African hominin populations. Here, Israel Hershkovitz, Yossi Zaidner and colleagues present fossil, artifact, and radiometric evidence from the Levant region of the Middle East that illustrates this complexity. According to Hershkovitz et al., the newly discovered Nesher Ramla Homo exhibits anatomical features that are more archaic than contemporaneous Eurasian Neanderthals and the modern humans who also lived in the Levant. The findings indicate that this archaic lineage may represent one of the last surviving populations of Middle Pleistocene Homo in southwest Asia, Africa and Europe. In the companion study, Zaidner et al. provide the archaeological context of the new fossils, reporting on the associated radiometric ages, artifact assemblages and the behavioral and environmental insights they offer. Zaidner et al. show that the Nesher Ramla Homo were well versed in technologies that were previously only known among H. sapiens and Neanderthals. Together, the findings provide archaeological support for close cultural interactions and genetic admixture between different human lineages before 120,000 years ago. This may help explain the variable expression of the dental and skeletal features of later Levantine fossils. "The interpretation of the Nesher Ramla fossils and stone tools will meet with different reactions among paleoanthropologists. Notwithstanding, the age of the Nesher Ramla material, the mismatched morphological and archaeological affinities, and the location of the site at the crossroads of Africa and Eurasia make this a major discovery," writes Marta Lahr in an accompanying Perspective.

###

A new type of Homo unknown to science

Dramatic discovery in Israeli excavation

IMAGE: .STATIC SKULL & MANDIBLE & PARIETAL ORTHOGRAPHIC. view more

CREDIT: TEL AVIV UNIVERSITY

- The discovery of a new Homo group in this region, which resembles Pre-Neanderthal populations in Europe, challenges the prevailing hypothesis that Neanderthals originated from Europe, suggesting that at least some of the Neanderthals' ancestors actually came from the Levant.

- The new finding suggests that two types of Homo groups lived side by side in the Levant for more than 100,000 years (200-100,000 years ago), sharing knowledge and tool technologies: the Nesher Ramla people who lived in the region from around 400,000 years ago, and the Homo sapiens who arrived later, some 200,000 years ago.

- The new discovery also gives clues about a mystery in human evolution: How did genes of Homo sapiens penetrate the Neanderthal population that had presumably lived in Europe long before the arrival of Homo sapiens?

- The researchers claim that at least some of the later Homo fossils found previously in Israel, like those unearthed in the Skhul and Qafzeh caves, do not belong to archaic (early) Homo sapiens, but rather to groups of mixed Homo sapiens and Nesher Ramla lineage.

Nesher Ramla Homo type - a prehistoric human previously unknown to science: Researchers from Tel Aviv University and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem have identified a new type of early human at the Nesher Ramla site, dated to 140,000 to 120,000 years ago. According to the researchers, the morphology of the Nesher Ramla humans shares features with both Neanderthals (especially the teeth and jaws) and archaic Homo (specifically the skull). At the same time, this type of Homo is very unlike modern humans - displaying a completely different skull structure, no chin, and very large teeth. Following the study's findings, researchers believe that the Nesher Ramla Homo type is the 'source' population from which most humans of the Middle Pleistocene developed. In addition, they suggest that this group is the so-called 'missing' population that mated with Homo sapiens who arrived in the region around 200,000 years ago - about whom we know from a recent study on fossils found in the Misliya cave.

Two teams of researchers took part in the dramatic discovery, published in the prestigious Science journal: an anthropology team from Tel Aviv University headed by Prof. Israel Hershkovitz, Dr. Hila May and Dr. Rachel Sarig from the Sackler Faculty of Medicine and the Dan David Center for Human Evolution and Biohistory Research and the Shmunis Family Anthropology Institute, situated in the Steinhardt Museum at Tel Aviv University; and an archaeological team headed by Dr. Yossi Zaidner from the Institute of Archaeology at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Timeline: The Nesher Ramla Homo type was an ancestor of both the Neanderthals in Europe and the archaic Homo populations of Asia.

Prof.Israel Hershkovitz: "The discovery of a new type of Homo" is of great scientific importance. It enables us to make new sense of previously found human fossils, add another piece to the puzzle of human evolution, and understand the migrations of humans in the old world. Even though they lived so long ago, in the late middle Pleistocene (474,000-130,000 years ago), the Nesher Ramla people can tell us a fascinating tale, revealing a great deal about their descendants' evolution and way of life."

The important human fossil was found by Dr. Zaidner of the Hebrew University during salvage excavations at the Nesher Ramla prehistoric site, in the mining area of the Nesher cement plant (owned by Len Blavatnik) near the city of Ramla. Digging down about 8 meters, the excavators found large quantities of animal bones, including horses, fallow deer and aurochs, as well as stone tools and human bones. An international team led by the researchers from Tel Aviv and Jerusalem identified the morphology of the bones as belonging to a new type of Homo, previously unknown to science. This is the first type of Homo to be defined in Israel, and according to common practice, it was named after the site where it was discovered - the Nesher Ramla Homo type.

CAPTION

Fossil remains of skull and jaw.

CREDIT

Tel Aviv University

Dr. Yossi Zaidner: "This is an extraordinary discovery. We had never imagined that alongside Homo sapiens, archaic Homo roamed the area so late in human history. The archaeological finds associated with human fossils show that "Nesher Ramla Homo" possessed advanced stone-tool production technologies and most likely interacted with the local Homo sapiens". The culture, way of life, and behavior of the Nesher Ramla Homo are discussed in a companion paper also published in Science journal today.

Prof. Hershkovitz adds that the discovery of the Nesher Ramla Homo type challenges the prevailing hypothesis that the Neanderthals originated in Europe. "Before these new findings," he says, "most researchers believed the Neanderthals to be a 'European story', in which small groups of Neanderthals were forced to migrate southwards to escape the spreading glaciers, with some arriving in the Land of Israel about 70,000 years ago. The Nesher Ramla fossils make us question this theory, suggesting that the ancestors of European Neanderthals lived in the Levant as early as 400,000 years ago, repeatedly migrating westward to Europe and eastward to Asia. In fact, our findings imply that the famous Neanderthals of Western Europe are only the remnants of a much larger population that lived here in the Levant - and not the other way around."

According to Dr. Hila May, despite the absence of DNA in these fossils, the findings from Nesher Ramla offer a solution to a great mystery in the evolution of Homo: How did genes of Homo sapiens penetrate the Neanderthal population that presumably lived in Europe long before the arrival of Homo sapiens? Geneticists who studied the DNA of European Neanderthals have previously suggested the existence of a Neanderthal-like population which they called the 'missing population' or the 'X population' that had mated with Homo sapiens more than 200,000 years ago. In the anthropological paper now published in Science, the researchers suggest that the Nesher Ramla Homo type might represent this population, heretofore missing from the record of human fossils. Moreover, the researchers propose that the humans from Nesher Ramla are not the only ones of their kind discovered in the region, and that some human fossils found previously in Israel, which have baffled anthropologists for years - like the fossils from the Tabun cave (160,000 years ago), Zuttiyeh cave (250,000), and Qesem cave (400,000) - belong to the same new human group now called the Nesher Ramla Homo type.

"People think in paradigms," says Dr. Rachel Sarig. "That's why efforts have been made to ascribe these fossils to known human groups like Homo sapiens, Homo erectus, Homo heidelbergensis or the Neanderthals. But now we say: No. This is a group in itself, with distinct features and characteristics. At a later stage small groups of the Nesher Ramla Homo type migrated to Europe - where they evolved into the 'classic' Neanderthals that we are familiar with, and also to Asia, where they became archaic populations with Neanderthal-like features. As a crossroads between Africa, Europe and Asia, the Land of Israel served as a melting pot where different human populations mixed with one another, to later spread throughout the Old World. The discovery from the Nesher Ramla site writes a new and fascinating chapter in the story of humankind."

Prof. Gerhard Weber, an associate from Vienna University, argues that the story of Neanderthal evolution will be told differently after this discovery: "Europe was not the exclusive refugium of Neanderthals from where they occasionally diffused into West Asia. We think that there was much more lateral exchange in Eurasia, and that the Levant is geographically a crucial starting point, or at a least bridgehead, for this process."

CAPTION

(Left to Right): Israel Hershkovitz, Marion Prevost, Hila May, Rachel Sarig and Yossi Zaidner

CREDIT

Tel Aviv University

Link to the research video:

https:/

Link to the research video:

https:/

Static skull & mandible & parietal orthographic (also attached as a PNG file):

New fossil discovery from Israel points to complicated evolutionary process

IMAGE: THE NESHER RAMLA HUMAN MANDIBLE (LEFT) AND PARIETAL BONE (RIGHT). view more

CREDIT: AVI LEVIN AND ILAN THEILER, SACKLER FACULTY OF MEDICINE, TEL AVIV UNIVERSITY

BINGHAMTON, N.Y. -- Analysis of recently discovered fossils found in Israel suggest that interactions between different human species were more complex than previously believed, according to a team of researchers including Binghamton University anthropology professor Rolf Quam.

The research team, led by Israel Hershkovitz from Tel Aviv University, published their findings in Science, describing recently discovered fossils from the site of Nesher Ramla in Israel. The Nesher Ramla site dates to about 120,000-140,000 years ago, towards the very end of the Middle Pleistocene time period.

The human fossils were found by Dr. Zaidner of the Hebrew University during salvage excavations at the Nesher Ramla prehistoric site, near the city of Ramla. Digging down about 8 meters, the excavators found large quantities of animal bones, including horses, fallow deer and aurochs, as well as stone tools and human bones. The human fossils consist of a partial cranial vault and a mandible. Researchers made virtual reconstructions of the fossils to analyze them using sophisticated computer software programs and to compare them with other fossils from Europe, Africa and Asia. The results suggest that the Nesher Ramla fossils represent late survivors of a population of humans who lived in the Middle East during the Middle Pleistocene period.

"The oldest fossils that show Neandertal features are found in Wesern Europe, so researchers generally believe the Neandertals originated there," said Quam. "However, migrations of different species from the Middle East into Europe may have provided genetic contributions to the Neandertal gene pool during the course of their evolution."

The finds from Nesher Ramla are noteworthy because they sample a time period in the Middle East with few fossils, so they are important additions to the growing fossil record from the region. Other fossils from this approximate time period are difficult to classify taxonomically since they seem to show a combination of features seen in both Neandertals and modern humans. The Nesher Ramla fossils seem more Neandertal-like in the mandible and less Neandertal-like in the cranial vault, but are clearly distinct from modern humans. This pattern matches what has been suggested for both Neandertals and modern humans, where the diagnostic skeletal features of each species appear first in the facial region and later on the cranial vault.

Describing the significance of the find, Dr. Hershkovitz said: "It enables us to make new sense of previously found human fossils, add another piece to the puzzle of human evolution, and understand the migrations of humans in the old world. Even though they lived so long ago, in the late middle Pleistocene, the Nesher Ramla people can tell us a fascinating tale, revealing a great deal about their descendants' evolution and way of life."

CAPTION

Transparent view of the mandibular body and tooth roots in the Nesher Ramla mandible

CREDIT

Ariel Pokhojaev, Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University

The researchers were careful not to attribute the Nesher Ramla fossils to a new species. Rather, they grouped them together with earlier fossils from several sites in the Middle East that have been difficult to classify and considered all of them to represent a local population of humans that occupied the region between about 420,000-120,000. Given the fact that the Middle East sits at the crossroads of three continents, it is likely that different human groups moved into and out of the region regularly, exchanging genes with the local inhabitants. This scenario might explain the variable anatomical features in these fossils, with the Nesher Ramla fossils representing the latest known survivors of this localized Middle Pleistocene population.

"This is a complicated story, but what we are learning is that the interactions between different human species in the past were much more convoluted than we had previously appreciated," said Quam.

###

The study, "A Middle Pleistocene Homo from Nesher Ramla, Israel," was published in Science, along with a companion paper discussing the culture, way of life, and behavior of the Nesher Ramla Homo.

CAPTION

Virtual reconstruction of the Nesher Ramla mandible and molar.

CREDIT

: Ariel Pokhojaev, Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University