The loss of employer-sponsored health insurance can be a serious concern for older people

BE$T HEALTHCARE MONEY CAN BUY

Michael Kerr thought he would be back to work by now. When the 52-year-old from Reading, Pa., was put on furlough from his retail manager position in mid-March, he figured the business would reopen by April, reinstating him and other employees.

But as his furlough dragged on into June, he realized his job loss would become permanent, leaving him without income or his employer-sponsored health insurance.

"I felt like I needed to cover myself in bubble wrap and stay in the house," he said. "Every ache and pain got a little bit more scary."

Kerr is one of millions of American workers who have lost their job-based health insurance during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Kaiser Family Foundation has estimated that 27 million Americans could lose their employer-sponsored insurance and become uninsured due to the pandemic. Older workers under age 65 are among the most vulnerable.

Those numbers are staggering to people such as Kerr, who not only have to pay higher premiums for health insurance as they get older but may also have a harder time finding a new job, even when the economy isn't in a recession. "The closer you get to 60, the more difficult and scary it gets," he said. "Even by then, you've still got five more years to muddle through before getting government assistance."

Stan Dorn, director of the National Center for Coverage Innovation for the consumer group Families U.S., says that loss of insurance among people in the age range of 45 to 64 can be dire, as they often have greater health costs in medications or chronic conditions. "These folks are more expensive for an employer than younger adults because the average cost of health insurance is more for them," he said. And that added cost could be "an extra incentive to get rid of them."

The loss of health insurance for this group and others could also have a severe impact on the economy, Dorn said.

"When patients don't come to the hospital because they don't have insurance anymore, that means revenue dries up," he noted. "And those hospitals, clinics, and other providers would have to lay off staff."

Dorn also fears that the economy will continue to see more layoffs into the fall, and with it, more people losing their job-based health insurance. He thinks that could lead some people to delay or go without the care they need simply because they can no longer afford it.

"Patients with chronic conditions won't be able to afford their prescriptions, or they'll cut their pills in half," he said. "We'll see more people playing Russian roulette with their lives."

When the Affordable Care Act was passed in 2010, it increased coverage in two ways: by expanding Medicaid for the poor and improving plans for individuals. For the latter, the act set up a system so that nearly 90% of applicants received subsidies that reduced monthly premiums. The act also increased insurance protections for consumers, by banning plans that had lifetime caps on coverage or didn't cover preexisting conditions. More than 20 million people were able to get insurance. But over time, the law's regulations have been weakened, making room for new and cheaper plans with lesser coverage to enter the marketplace.

When Kerr realized that his furlough would turn into a permanent layoff and that his benefits would come to an end, he tried to navigate the health insurance marketplace on his own. But he quickly grew confused by the discrepancies in cost and coverage between all the available options.

"I almost made a bad decision on a plan that would've been more expensive and the coverage a lot less," he said of a plan through Oscar Health, which started providing coverage in the Philadelphia region only this year. "Health care really should be simplified somehow."

Kerr sought out the help of Young's Insurance Services, a health and life insurance brokerage agency based in Norristown. James Long, an agent there who frequently works with people in Kerr's age group, says that people in similar situations often have only two options: extend their employer-sponsored coverage by enrolling in COBRA, or find a plan through the marketplace and hope for discounts through subsidies. Long and agents like him are paid on commission, through marketing dollars incorporated into all policies.

Fortunately, Kerr qualified for some subsidies and was able to get an affordable plan through the marketplace, saving him from a COBRA option that was beyond his price range. But Long says that for people who are unable to receive subsidies, COBRA tends to be the better option.

Long often sees confusion among clients about how COBRA works. "Lots of people think it's its own health plan," he said. "But they're actually continuing on the same plan from their former employer, just now paying full price for it" without their employer's contribution.

That full price can lead to sticker shock, as Long notes that COBRA often falls in the range of $600 to $800 a month. Despite that jump in monthly cost, Long says that "equivalent plans on the marketplace without subsidies could be double that price."

David Grande, director of policy at the University of Pennsylvania's Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics, agrees with Long that COBRA might be the best choice for some people. For a person to qualify for subsidies, he notes that a person's household income needs to be below 400% of the poverty level, or $86,880 for a family of three. "If you have the financial resources for COBRA, that's probably the best option."

Still, Grande bemoans the lack of federal intervention on health care, especially as pandemic-related economic damage grows more permanent. He thinks, like Kerr, that navigating the health-care marketplace is too confusing, and that there's a lot of misunderstanding around who qualifies for subsidies and what the different options are.

"There needs to be a strong national effort to make subsidized coverage advertised, available, and easy to access," he said. "We're seeing the limits of the Affordable Care Act through individuals who don't qualify for subsidies, who probably should be subsidized at a point like this."

Some of the solutions Grande sees for these problems would be to expand Medicaid in states that haven't already done so, increasing the number of people who are able to enroll. (Pennsylvania and New Jersey have both expanded Medicaid.)

State-based exchanges, which Pennsylvania is set to begin in 2021, could help cut costs for individuals, as well, but he says that bigger issues surround who qualifies for subsidies. Those regulations can be changed only by the federal government, he noted.

Ellen Grubawsky, another client of Young's Insurance Services, also had to find new coverage after her furlough became a permanent layoff at a company where she had worked for 30 years. But at age 62, the Perkiomenville resident is more worried about securing a new job before becoming eligible for Medicare at 65.

"I'm uneasy about finding a job when the time comes, but I just have to wait and see what happens," she said.

Though Grubawsky qualified for subsidies that gave her discounted options, she says, the final added cost of almost $300 a month on her new plan is one more bill that's increasingly difficult to pay without a steady income. Worse yet, she has concerns that her new insurance has less coverage than her job-based plan. "I'm not even sure the plan I picked is the best one."

While enrolling in a new plan has made Grubawsky feel more secure about her situation, she still feels uncertain about her finances for the future. She hasn't ruled out collecting her Social Security early or considering a reverse mortgage (a loan that allows homeowners over 62 to draw out part of their home's equity as income) if the economy doesn't improve. Though she's still able to support herself through her severance package, Grubawsky acknowledged "that money only goes so far."

"It's very scary," she said. "I feel very uneasy about the whole situation.

©2020 The Philadelphia Inquirer

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

The density of red foxes is increasing in Norway’s mountainous areas. The more trash and food waste red foxes have access to, the greater their numbers. This photo was taken with a game camera and shows a red fox that has found food. Credit: NINA, game camera

The density of red foxes is increasing in Norway’s mountainous areas. The more trash and food waste red foxes have access to, the greater their numbers. This photo was taken with a game camera and shows a red fox that has found food. Credit: NINA, game camera Food waste left along the road at Dovre – just the kind of items that attract scavengers. Credit: Lars Rød-Eriksen

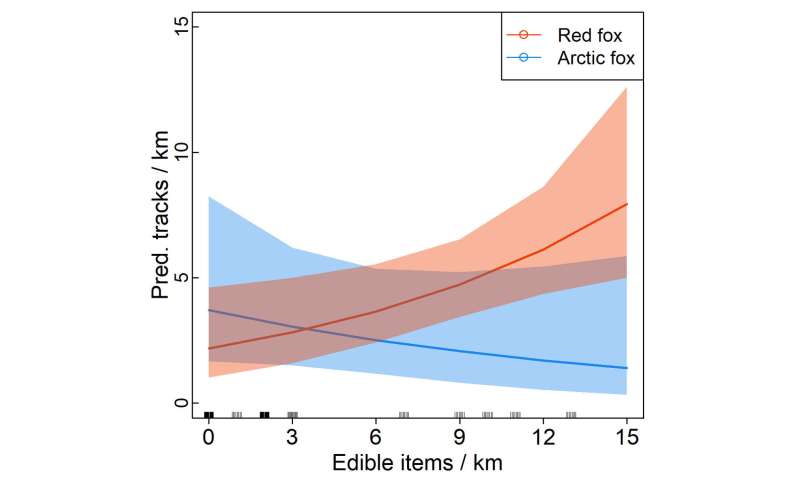

Food waste left along the road at Dovre – just the kind of items that attract scavengers. Credit: Lars Rød-Eriksen The graph shows that the number of red fox tracks per kilometre (y-axis) increases with the amount of edible waste (x-axis).

The graph shows that the number of red fox tracks per kilometre (y-axis) increases with the amount of edible waste (x-axis). A lot of trash means few Arctic foxes. We found that the Arctic fox doesn’t tend to stay close to the road – probably not because it isn’t attracted to the road, but because the red fox’s presence makes it stay away, the researcher says. The photo was taken in Lesja municipality. Credit: NINA, game camera

A lot of trash means few Arctic foxes. We found that the Arctic fox doesn’t tend to stay close to the road – probably not because it isn’t attracted to the road, but because the red fox’s presence makes it stay away, the researcher says. The photo was taken in Lesja municipality. Credit: NINA, game camera