The singer, who was admitted to an Australian hospital with husband Tom Hanks, says she was given chloroquine after developing a fever of 38.9C

Naaman Zhou@naamanzhou Wed 15 Apr 2020

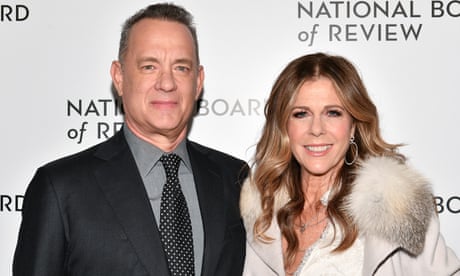

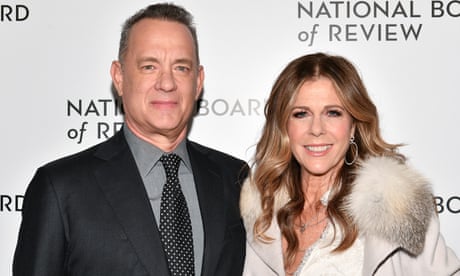

Tom Hanks and Rita Wilson tested positive for coronavirus in March in Australia. The singer says she suffered ‘extreme side effects’ from chloroquine. Photograph: Monica Almeida/Reuters

The singer Rita Wilson has claimed to have suffered “extreme side effects” after being treated with the experimental Covid-19 drug chloroquine in an Australian hospital.

Wilson, who was touring Australia, and her husband, Tom Hanks, who was filming a Baz Luhrmann film about Elvis Presley, both tested positive for Covid-19 on 12 March while in Australia.

The drugs chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine are used to treat malaria, but their ability to treat Covid-19 is still disputed by experts, despite being touted by the US president, Donald Trump, as a “gamechanger”.

Wilson and Hanks were admitted to Gold Coast University hospital in Queensland for treatment, where Wilson said she was given chloroquine after she developed a fever of 38.9C.

The singer Rita Wilson has claimed to have suffered “extreme side effects” after being treated with the experimental Covid-19 drug chloroquine in an Australian hospital.

Wilson, who was touring Australia, and her husband, Tom Hanks, who was filming a Baz Luhrmann film about Elvis Presley, both tested positive for Covid-19 on 12 March while in Australia.

The drugs chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine are used to treat malaria, but their ability to treat Covid-19 is still disputed by experts, despite being touted by the US president, Donald Trump, as a “gamechanger”.

Wilson and Hanks were admitted to Gold Coast University hospital in Queensland for treatment, where Wilson said she was given chloroquine after she developed a fever of 38.9C.

“They gave me chloroquine,” she told American TV channel CBS. “I know people have been talking about this drug. But I can only tell you that – I don’t know if the drug worked or if it was just time for the fever to break.

“My fever did break but the chloroquine had such extreme side effects, I was completely nauseous, I had vertigo and my muscles felt very weak … I think people have to be very considerate about that drug.”

A spokeswoman for Gold Coast University hospital would not confirm whether Hanks and Wilson were given chloroquine, but said that “selected patients” did receive the drug.

“Gold Coast Health has used a variety of medication in patients with more severe Covid-19,” a spokeswoman said. “Chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine and lopinavir-ritonavir have been used on selected patients.”

“Gold Coast Health has used a variety of medication in patients with more severe Covid-19,” a spokeswoman said. “Chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine and lopinavir-ritonavir have been used on selected patients.”

Trump proclaimed the chemical’s effectiveness in March, but the US’s top infectious diseases adviser, Dr Anthony Fauci, has warned that there is not enough medical evidence to prove that it is useful.

2:59 Trump grilled over continued promotion of hydroxychloroquine to treat coronavirus – video

Australian researchers have also said it could cause potentially life-threatening side-effects, such as heart damage.

In March, a man in Arizona died after taking chloroquine phosphate – a chemical used to clean fish tanks – after Trump’s advice. “Trump kept saying it was basically pretty much a cure,” his wife told NBC.

Last week, the Australian Health Protection Principal Committee – the expert panel on health emergencies – recommended against using the drugs in hospitals, contradicting the federal health department.

The department has told hospitals they can prescribe the drug “in a controlled environment in the treatment of severely ill patients in hospital”, after the government waived therapeutic goods registration requirements to fast-track their import into Australia.

Wilson and Hanks have both recovered from the illness, and said their blood had been taken for a study to determine the level of antibodies they developed.

CBS This Morning(@CBSThisMorning)

WATCH: In her first interview since her COVID-19 diagnosis, @RitaWilson says she's feeling great — and giving back.

Wilson told @GayleKing about the story behind her #HipHopHooray remix benefiting @MusiCares, her journey to recovery, and her symptoms when she first got sick. pic.twitter.com/yF3IZrFjCSApril 14, 2020

Q&A

2:59 Trump grilled over continued promotion of hydroxychloroquine to treat coronavirus – video

Australian researchers have also said it could cause potentially life-threatening side-effects, such as heart damage.

In March, a man in Arizona died after taking chloroquine phosphate – a chemical used to clean fish tanks – after Trump’s advice. “Trump kept saying it was basically pretty much a cure,” his wife told NBC.

Last week, the Australian Health Protection Principal Committee – the expert panel on health emergencies – recommended against using the drugs in hospitals, contradicting the federal health department.

The department has told hospitals they can prescribe the drug “in a controlled environment in the treatment of severely ill patients in hospital”, after the government waived therapeutic goods registration requirements to fast-track their import into Australia.

Wilson and Hanks have both recovered from the illness, and said their blood had been taken for a study to determine the level of antibodies they developed.

CBS This Morning(@CBSThisMorning)

WATCH: In her first interview since her COVID-19 diagnosis, @RitaWilson says she's feeling great — and giving back.

Wilson told @GayleKing about the story behind her #HipHopHooray remix benefiting @MusiCares, her journey to recovery, and her symptoms when she first got sick. pic.twitter.com/yF3IZrFjCSApril 14, 2020

No comments:

Post a Comment