Despite international efforts to abolish slavery, it is well and truly alive in certain parts of the world. Global warming and the COVID-19 pandemic are not helping matters.

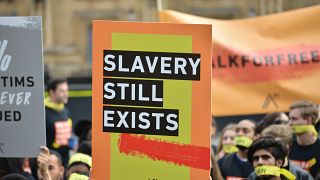

There are frequent anti-slavery protests but these do not always lead to change

Cheickna Diarra is from the village of Baramabougou in the region of Kayes in Mali, where what is known as "descent-based or hereditary slavery" is widespread.

Diarra was abused by people who saw themselves as his "masters" before he finally fled to the capital Bamako, where he now lives in a camp for internally displaced people (IDPs).

In 2019, he almost died after visiting a friend. "On my way home, about 20 young villagers barred my way without even asking where I was from, what I was doing there," he told DW. "They fell upon me and started hitting me with sticks until I fell down and lost consciousness."

He only survived because the cries of his relatives alerted the other villagers who came to his help.

"We stopped cultivating our fields in 2018," he explained. "Those claiming to be our masters banned us from going to the store and the fields, as well as from leaving the village."

He filed a complaint against unknown persons for maltreatment but to no avail. Many of the 130 others in his IDP camp have filed similar complaints in vain.

'Authorities always find a way out'

Temedt is an NGO that campaigns against slavery in Mali. Its vice-president Raichatou Walet Altanata told DW that progress is slow. "We have been denouncing the phenomenon since 2006. But none of our cases have gone to court on the grounds of slavery. The authorities always find a way out." She said that sometimes violence or crime is acknowledged but slavery, the real issue at stake, is never taken into account.

She pointed out that this goes against international conventions to abolish slavery that Mali has ratified, as well as the constitution, which also states that human dignity is sacred and inviolable.

Even those who manage to escape slavery are often doomed to a life of poverty

According to the human rights NGO Anti-Slavery International, descent-based slavery "can still be found across the Sahel belt of Africa, including Mauritania, Niger, Mali, Chad and Sudan."

"People born into descent-based slavery face a lifetime of exploitation and are treated as property by their so-called 'masters.' They work without pay, herding animals, working in the fields or in their masters' homes. They can be inherited, sold or given away as gifts or wedding presents."

"Many other African societies also have a traditional hierarchy where people are known to be the descendants of slaves or slave-owners."

In 1981, Mauritania became one of the last countries in the world to ban slavery.

However, it has yet to be abolished in reality.

'Still a long way to go'

On December 2, 1949 the United Nations General Assembly approved the Convention for the Suppression of the Traffic in Persons and of the Exploitation of the Prostitution of Others. The date later became known as the International Day for the Abolition of Slavery.

The convention has lost none of its relevance today. "While much progress has been made in terms of understanding modern slavery and the driving forces behind it, we still have a very long way to go if we are going to end it for good," Anti-Slavery International CEO Jasmine O'Connor told DW. "Millions of people around the world are living in slavery and increasing pressures are making many more vulnerable to the tricks of traffickers."

According to the International Labor Organization (ILO), 40 million people were victims of modern slavery in 2016 and one in four were children.

People have been protesting against child labor for over a century. Today, children make up a quarter of those in forced labor.

Although modern slavery is not defined legally, it is often used as an umbrella term for practices such as forced labor, debt bondage, forced marriage, human trafficking and the forced recruitment of children in armed conflicts. Those who are most likely to be affected live in Africa, followed by the Asia-Pacific.

In 2016, 15.4 million people were in forced marriage and 24.9 million people were in forced labor, two thirds of whom were exploited in the private sector such as domestic work, construction or agriculture. 4.8 million were in forced sexual exploitation and 4 million were in forced labor imposed by state authorities.

Women are disproportionately affected by modern slavery, which sometimes involves sexual exploitation

More courageous action needed

Anti-Slavery International has called for more courageous and effective action and laws, as well as investigations and preventative measures to put an end to slavery across the world. CEO Jasmine O'Connor welcomed the fact that the G7 states have acknowledged the matter as one of great concern and said that there had been some legal and political successes with regard to hereditary slavery in west Africa. However, she feared that new statistics on slavery would show that numbers have gone up in the past five years.

"The past year has been marked by COVID-19 pandemic and climate change and we have seen how these factors are pushing more and more people into unplanned migration and precarious work, placing them at high risk of exploitation."