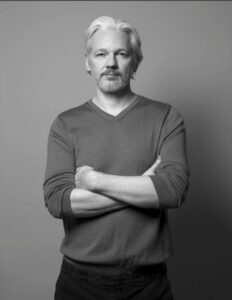

Finally Free, Assange Receives a Measure of Justice From the Council of Europe

Source: Council of Europe

The Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE), Europe’s foremost human rights body, overwhelmingly adopted a resolution on October 2 formally declaring WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange a political prisoner. The Council of Europe, which represents 64 nations, expressed deep concern at the harsh treatment suffered by Assange, which has had a “chilling effect” on journalists and whistleblowers around the world.

In the resolution, PACE notes that many of the leaked files WikiLeaks published “provide credible evidence of war crimes, human rights abuses, and government misconduct.” The revelations also “confirmed the existence of secret prisons, kidnappings and illegal transfers of prisoners by the United States on European soil.”

According to the terms of a plea deal with the U.S. Department of Justice, Assange pled guilty on June 25 to one count of conspiracy to obtain documents, writings and notes connected with the national defense under the U.S. Espionage Act. Without the deal, he was facing 175 years in prison for 18 charges in an indictment filed by the Trump administration and pursued by the Biden administration, stemming from WikiLeaks’ publication of evidence of war crimes committed by the U.S. in Iraq, Afghanistan and Guantánamo Bay. After his plea, Assange was released from custody with credit for the five years he had spent in London’s maximum-security Belmarsh Prison.

The day before PACE passed its resolution, Assange delivered a powerful testimony to the Council of Europe’s Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights. This was his first public statement since his release from custody four months ago, after 14 years in confinement – nine in the Ecuadorian Embassy in London and five in Belmarsh. “Freedom of expression and all that flows from it is at a dark crossroads,” Assange told the parliamentarians.

A “Chilling Effect and a Climate of Self-Censorship”

The resolution says that “the disproportionately harsh charges” the U.S. filed against Assange under the Espionage Act, “which expose him to a risk of de facto life imprisonment,” together with his conviction “for — what was essentially — the gathering and publication of information,” justify classifying him as a political prisoner, under the definition set forth in a PACE resolution from 2012 defining the term. Assange’s five-year incarceration in Belmarsh Prison was “disproportionate to the alleged offence.”

Noting that Assange is “the first publisher to be prosecuted under [the Espionage Act] for leaking classified information obtained from a whistleblower,” the resolution expresses concern about the “chilling effect and a climate of self-censorship for all journalists, editors and others who raise the alarm on issues that are essential to the functioning of democratic societies.” The resolution also notes that “information gathering is an essential preparatory step in journalism” which is protected by the right to freedom of expression guaranteed by the European Court of Human Rights.

The resolution cites the conclusion of Nils Melzer, UN Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, that Assange had been exposed to “increasingly severe forms of cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, the cumulative effects of which can only be described as psychological torture.”

Condemning “transnational repression,” PACE was “alarmed by reports that the CIA was discreetly monitoring Mr. Assange in the Ecuadorian embassy in London and that it was allegedly planning to poison or even assassinate him on British soil.” The CIA has raised the “state secrets” privilege in a civil lawsuit filed by two attorneys and two journalists over that illegal surveillance.

In the U.S., “the concept of state secrets is used to shield executive officials from criminal prosecution for crimes such as kidnapping and torture, or to prevent victims from claiming damages,” the resolution notes. But “the responsibility of State agents for war crimes or serious human rights violations, such as assassinations, enforced disappearances, torture or abductions, does not constitute a secret that must be protected.”

Moreover, the resolution expresses deep concern that, according to publicly available evidence, no one has been held to account for the war crimes and human rights violations committed by U.S. state agents and decries the “culture of impunity.”

The resolution says there is no evidence anyone has been harmed by WikiLeaks’ publications and “regrets that despite Mr Assange’s disclosure of thousands of confirmed — previously unreported — deaths by U.S. and coalition forces in Iraq and Afghanistan, he has been the one accused of endangering lives.”

Assange’s Testimony

The testimony Assange provided to the committee was poignant. “I eventually chose freedom over realizable justice … Justice for me is now precluded,” Assange testified. “I am not free today because the system worked. I am free today after years of incarceration because I pled guilty to journalism.” He added, “I pled guilty to seeking information from a source. I pled guilty to obtaining information from a source. And I pled guilty to informing the public what that information was.” His source was whistleblower Chelsea Manning, who provided the documents and reports to WikiLeaks. “Journalism is not a crime,” Assange said. “It is a pillar of a free and informed society.”

Assange described the transition from the years he spent in a maximum-security prison to testifying before the European parliamentarians as a “profound and surreal shift.” Speaking of his isolation for years in a small cell, he said “it strips away one’s sense of self, leaving only the raw essence of existence.” Assange said, “I’m yet not fully equipped to speak about what I have endured. The relentless struggle to stay alive, both physically and mentally. Nor can I speak yet about the death by hanging, murder and medical neglect of my fellow prisoners.”

Perhaps the most infamous publication by WikiLeaks was the 2007 “Collateral Murder” video, which depicts a U.S. Army Apache attack helicopter crew targeting and killing 12 unarmed civilians in Baghdad, including two Reuters journalists, as well as a man who came to rescue the wounded. The release of that video “stirred public debate,” Assange testified. “Now, every day there are live streaming horrors from the wars in Ukraine and the war in Gaza.” He cited “hundreds of journalists” killed in those wars.

Addressing the danger journalists face, Assange declared, “The criminalization of news-gathering activities is a threat to investigative journalism everywhere. I was formally convicted by a foreign power for asking, for receiving and publishing truthful information about that power.” He noted, “The fundamental issue is simple. Journalists should not be prosecuted for doing their jobs.”

Assange predicted “more impunity, more secrecy, more retaliation for telling the truth and more self-censorship” in the future. “Journalists must be activists for the truth,” he said, mentioning the importance of “journalistic solidarity.”

Although Assange expected some sort of legal harassment as a result of WikiLeaks’ publications and was ready “to fight for that,” he said “my naivete was believing in the law. When push comes to shove, laws are just pieces of paper, and they can be reinterpreted for political expediency.”

Assange observed that laws are made by the ruling class, who simply reinterpret them when the rules don’t serve their ends. Describing the legal process in his case, Assange noted that “all judges, whether they were finding in my favor or not in the United Kingdom, showed extraordinary deference to the United States.”

PACE Urges US to Investigate War Crimes

The resolution calls on the U.S., the U.K., the member and observer States of the Council of Europe, and media outlets to take actions to address its concerns.

It calls on the U.S., an observer State, to reform the Espionage Act of 1917 to exclude from its operation journalists, editors and whistleblowers who disclose classified information with the aim of informing the public of serious crimes, such as torture or murder. In order to obtain a conviction for violation of the Act, the government should be required to prove a malicious intent to harm national security. It also calls on the U.S. to investigate the allegations of war crimes and other human rights violations exposed by Assange and Wikileaks.

PACE called on the U.K. to review its extradition laws to exclude extradition for political offenses, as well as conduct an independent review of the conditions of Assange’s treatment while at Belmarsh, to see if it constituted torture, or inhuman or degrading treatment.

In addition, the resolution urges the States of the Council of Europe to further improve their protections for whistleblowers, and to adopt strict guidelines to prevent governments from classifying documents as defense secrets when not warranted.

Finally, the resolution urges media outlets to establish rigorous protocols for handling and verifying classified information, to ensure responsible reporting and avoid any risk to national security and the safety of informants and sources.

Although PACE doesn’t have the authority to make laws, it can urge the States of the Council of Europe to take action. Since Assange never had the opportunity to litigate the denial of his right to freedom of expression, the resolution of the Council of Europe is particularly significant as he seeks a pardon from U.S. President Joe Biden.

Related Posts

Chip Gibbons -- March 31, 2024

US Refuses to Assure UK Judges That Assange Won’t Be Executed If He’s Extradited

Marjorie Cohn -- February 29, 2024

“Free the Truth”: The Belmarsh Tribunal on Julian Assange & Defending Press Freedom

Amy Goodman -- January 01, 2024

Basic Press Freedoms Are at Stake in the Julian Assange Case

Chip Gibbons -- February 27, 2024

Five Years At Belmarsh: A Chronicle Of Julian Assange’s Imprisonment

Kevin Gosztola -- April 12, 2024

Marjorie Cohn is professor emerita at Thomas Jefferson School of Law, dean of the People’s Academy of International Law, and past president of the National Lawyers Guild. She sits on the national advisory boards of Assange Defense and Veterans For Peace. A member of the bureau of the International Association of Democratic Lawyers, she is the U.S. representative to the continental advisory council of the Association of American Jurists. Her books include Drones and Targeted Killing: Legal, Moral and Geopolitical Issues.

Assange Was A Political Prisoner, Council Of Europe Parliamentarians Declare In Vote

Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (Source)

The Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, or PACE, approved a resolution that states WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange was prosecuted and detained in the United Kingdom as a political prisoner.

Þórhildur Sunna Ævarsdóttir, the general rapporteur for political prisoners and an Icelandic parliamentarian who serves on the Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights, drafted the resolution, which passed by a vote of 88-13.

The resolution urged the United States to reform the Espionage Act and “make its application conditional to the presence of a malicious intent to harm the national security of the United States or to aid a foreign power” and “exclude the application of the Espionage Act to publishers, journalists and whistleblowers,” especially those who try to inform the public about war crimes, torture, and illegal surveillance.

Assange, his wife Stella Assange, and WikiLeaks editor-in-chief Kristinn Hrafnsson were present for the debate and vote on the resolution. They cheered, clapped, and thanked the assembly.

The debate and vote on the resolution came after Assange testified before PACE’s Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights on October 1. It was his first public testimony since he accepted a plea deal that ended the United States Justice Department’s political case against him.

PACE’s consideration of Assange’s case was part of a wider examination by the assembly of the increased threats that journalists and whistleblowers face in Europe. A fact-finding visit to the U.K. by Ævarsdóttir occurred while Assange was still detained at Belmarsh.

“If you look at the definition of a political prisoner, Julian Assange and his case fulfills this definition,” Ævarsdóttir told the assembly. “He was convicted for engaging in acts of journalism. This is a clear instance of a politically motivated incarceration.”

She continued, “If it were any other country, if it were one of the countries that we are happy to point to having political prisoners on a regular basis here in the Parliamentary Assembly, I don’t think that there would be much of a question on whether or not this assembly is fit to determine whether someone is or is not a political prisoner. We did indeed ourselves create this definition.”

“What does this case say to those who risk their lives to report on corruption, war crimes, and human rights abuses? It says that if you dare to publish the truth you may face the full wrath of the law, however archaic and unjust the law is,” Ævarsdóttir stated. “It says that in the struggle between power and truth, power will prevail.”

Lesia Vasylenko, a parliamentarian from Ukraine, supported the resolution and agreed that the “biggest threat” presented by the Assange case was that journalists may now be prosecuted under the U.S. Espionage Act.

“Editors and publishers will start discussing whether they can publish classified information that contributes to public debate,” Vasylenko said. “The climate of self-censorship must be avoided at all costs so that our societies can remain free and hold their governments to account.”

Anna-Kristiina Mikkonen, a parliamentarian from Finland, recalled how the WikiLeaks publications had helped confirm “the existence of secret prisons as well as secret and illegal kidnapping transfers carried out by the United States [the CIA] on European territory.”

“The Assange case, and in particular the role of [Chelsea] Manning, is very good reason to try and achieve better protection for whistleblowers throughout the world,” Mikkonen said.

A “dotted line” could be drawn from the Assange case to impunity for the Spanish government “spying on dissident voices, lawyers, journalists, and politicians” in Catalonia, “destroying democracy and not addressing the WikiLeaks revelations on 125 German officials including [German Chancellor Angela] Merkel,” declared Spanish parliamentarian Laura Castel.

Castel also called out the illegal surveillance by the United States of Assange’s “privileged legal and medical conversations inside a sovereign embassy.” The CIA reportedly relied upon a Spanish security firm called UC Global to target Assange, his family, his lawyers, and associates that regularly visited him in Ecuador’s London embassy while he lived under political asylum.

Paul Gavan, a parliamentarian from Ireland, did not mince words in his remarks. “This week we saw the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe at its worst and at its best. Its worst moment was the continuing refusal to take a stand against a genocide being prosecuted against the Palestinian people. Its best moment was the powerful testimony of Julian Assange at the Committee for Legal Affairs yesterday.”

“I believe it was truly significant that Julian made a number of references both to Ukraine and Gaza and the deliberate murder of journalists in both locations.”

“One of the most frustrating things over the last five years is that a large chunk of the body politic both here and across Europe chose to bury their heads in the sand,” Gavan declared. “They chose to be silent in relation to this outrageous series of acts against this fine man. And it’s disappointing to note that this is the shortest list of political speakers for any debate this week.

“What does that tell us about the continuing silence? So the least we can do today is endorse this excellent report because our job is to defend media freedom.”

“Yes, Julian Assange has worked for human rights,” said French parliamentarian Emmanuel Fernandes. Assange revealed that the National Security Agency in the U.S. had “wiretapped three French presidents between 2006 and 2013.”

Fernandes linked the Assange case to the French government’s targeting of journalists. Particularly, Fernandes recalled, in 2023, Ariane Lavrilleux was “incarcerated for 39 hours.” French authorities seized her phone and computer. The attack on freedom of the press came two years after she revealed that “France was an accomplice in the extrajudicial killing of hundreds of people in Egypt.”

“What I do regret is that his release was not underpinned by a legal verdict. I think it would have been very important to have some kind of legal ruling, which would have provided greater legal certainty who dare to denounce illegal actions,” Austrian parliamentarian Petra Bayr argued. “So without a ruling from either a U.K. court or the European Court of Human Rights, this does leave something of a void. Which means that there’s a justified fear that such goings on will continue, and journalists won’t necessarily benefit from protection.”

Julian Pahlke, a parliamentarian from Germany, said that the case had ended with a deal that helped the United States “maintain their image.” It was crucial for PACE to advocate for an “umbrella of protection” against Espionage Act prosecutions against journalists, publishers, and civil society organizations in Council of Europe member states.

Multiple amendments were put forward by Richard Keen, a Conservative parliamentarian from the U.K. who formally dissented against the resolution. He complained that the resolution belittled the “fate of true political prisoners,” like those detained in Russia and insisted Assange was not tortured while he was held at Belmarsh.

As the time came for Keen to present his amendments for a vote, he meekly withdrew several of them. It was emblematic of how political elites in the Western world have quickly moved on from their campaign against Assange and WikiLeaks now that the case has ended and the media organization’s founder is free.

Keen was particularly annoyed by an amendment that condemned Assange’s detention at Belmarsh. “He was not detained as a political prisoner. That’s a simple matter of legal fact, and if we ignore that, I think we devalue the report.”

The assembly disregarded the U.K. parliamentarian’s griping and adopted the amendment.

Thirteen European parliamentarians voted against the resolution:

Altogether, the passage of a resolution recognizing that Assange was a political prisoner was an overdue act of solidarity with a journalist and an acknowledgment that another prosecution like it could easily happen if European countries do not stand up for media freedom and freedom of expression.

Anthony Bellanger, secretary general for the International Federation of Journalists praised the vote. “It’s a victory for press freedom, for all journalists across the world and for Assange after 12 years deprived of freedom. The fight for truth has never been so necessary.”

The names of the 13 European parliamentarians, who voted against the resolution and still apparently believe that the persecution against Assange was acceptable: Keen (U.K.), David Blencathra (U.K.), Sally-Ann Hart (U.K.), David Morris (U.K.), Katarzyna Sójka (Poland), Paweł Jabłoński (Poland), Hannes Germann (Switzerland), Martin Graf (Austria), Ricardo Dias Pinto (Spain), Vladimir Dordevic (Serbia), and Arminas Lydeka (Lithuania).

Unrealisable Justice: Julian Assange in Strasbourg

It was good to hear that voice again. A voice of provoking interest that pitter patters, feline across a parquet, followed by the usual devastating conclusion. Julian Assange’s last public address was made in the Ecuadorian Embassy in London. There, he was a guest vulnerable to the capricious wishes of changing governments. At Belmarsh Prison in London, he was rendered silent, his views conveyed through visitors, legal emissaries and his family.

It was good to hear that voice again. A voice of provoking interest that pitter patters, feline across a parquet, followed by the usual devastating conclusion. Julian Assange’s last public address was made in the Ecuadorian Embassy in London. There, he was a guest vulnerable to the capricious wishes of changing governments. At Belmarsh Prison in London, he was rendered silent, his views conveyed through visitors, legal emissaries and his family.

The hearing in Strasbourg on October 1, organised by the Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE), arose from concerns raised in a report by Iceland’s Thórhildur Sunna Ævarsdóttir, in which she expressed the view that Assange’s case was “a classic example of ‘shooting the messenger’.” She found it “appalling that Mr Assange’s prosecution was portrayed as if it was supposed to bring justice to some unnamed victims the existence of whom has never been proven, whereas perpetrators of torture or arbitrary detention enjoy absolute impunity.”

His prosecution, Ævarsdóttir went onto explain, had been designed to obscure and deflect the revelations found in WikiLeaks’ disclosures, among them abundant evidence of war crimes committed by US and coalition forces in Iraq and Afghanistan, instances of torture and arbitrary detention in the infamous Guantánamo Bay camp facility, illegal rendition programs implicating member states of the Council of Europe and unlawful mass surveillance, among others.

A draft resolution was accordingly formulated, expressing, among other things, alarm at Assange’s treatment and disproportionate punishment “for engaging in activities that journalists perform on a daily basis” which made him, effectively, a political prisoner; the importance of holding state security and intelligence services accountable; the need to “urgently reform the 1917 Espionage Act” to include conditional maliciousness to cause harm to the security of the US or aid a foreign power and exclude its application to publishers, journalists and whistleblowers.

Assange’s full testimony began with reflection and foreboding: the stripping away of his self in incarceration, the search, as yet, for words to convey that experience, and the fate of various prisoners who died through hanging, murder and medical neglect. While filled with gratitude by the efforts made by PACE and the Legal Affairs and Human Rights Committee, not to mention innumerable parliamentarians, presidents, prime ministers, even the Pope, none of their interventions “should have been necessary.” But they proved invaluable, as “the legal protections that did exist, many existed only on paper or were not effective in any remotely reasonable time frame.”

The legal system facing Assange was described as encouraging an “unrealisable justice”. Choosing freedom instead of purgatorial process, he could not seek it, the plea deal with the US government effectively barring his filing of a case at the European Court of Human Rights or a freedom of information request. “I am not free today because the system worked,” he insisted. “I am free today because after years of incarceration because I plead guilty to journalism. I plead guilty to seeking information from a source. I plead guilty to informing the public what that information was. I did not plead guilty to anything else.”

When founded, WikiLeaks was intended to enlighten people about the workings of the world. “Having a map of where we are lets us understand where we might go.” Power can be held to account by those informed, justice sought where there is none. The organisation did not just expose assassinations, torture, rendition and mass surveillance, but “the policies, the agreements and the structures behind them.”

Since leaving Belmarsh prison, Assange rued the abstracting of truth. It seemed “less discernible”. Much ground had been “lost” in the interim; truth had been battered, “undermined, attacked, weakened and diminished. I see more impunity, more secrecy, more retaliation for telling the truth and more self-censorship.”

Much of the critique offered by Assange focused on the source of power behind any legal actions. Laws, in themselves, “are just pieces of paper and they can be reinterpreted for political expedience”. The ruling class dictates them and reinterprets or changes them depending on circumstances.

In his case, the security state “was powerful enough to push for a reinterpretation of the US constitution,” thereby denuding the expansive, “black and white” effect of the First Amendment. Mike Pompeo, when director of the Central Intelligence Agency, simply lent on Attorney General William Barr, himself a former CIA officer, to seek the publisher’s extradition and re-arrest of Chelsea Manning. Along the way, Pompeo directed the agency to draw up plans of abduction and assassination while targeting Assange’s European colleagues and his family.

The US Department of Justice, Assange could only reflect, cared little for moderating tonic of legalities – that was something to be postponed to a later date. “In the meantime, the deterrent effect that it seeks, the retributive actions that it seeks, have had their effect.” A “dangerous new global legal position” had been established as a result: “Only US citizens have free speech rights. Europeans and other nationalities do not have free speech rights.”

PACE had, before it, an opportunity to set norms, that “the freedom to speak and the freedom to publish the truth are not privileges enjoyed by a few but rights guaranteed to all”. “The criminalisation of newsgathering activities is a threat to investigative journalism everywhere. I was formally convicted, by a foreign power, for asking for, receiving, and publishing truthful information about that power while I was in Europe.”

A spectator, reader or listener might leave such an address deflated. But it is fitting that a man subjected to the labyrinthine, life-draining nature of several legal systems should be the one to exhort to a commitment: that all do their part to keep the light bright, “that the pursuit of truth will live on, and the voices of the many are not silenced by the interests of the few.”

Handmaiden to the Establishment

Peter Greste’s Register of Journalists

When established, well fed and fattened, a credible professional tires from the pursuit. One can get complacent, flatulently confident, self-assured. From that summit, the inner lecturer emerges, along with a disease: false expertise.

The Australian journalist Peter Greste has faithfully replicated the pattern. At one point in his life, he was lean, hungry and determined to get the story. He seemed to avoid the perils of mahogany ridge, where many alcohol-soaked hacks scribble copy sensational or otherwise. There were stints as a freelancer covering the civil wars in Yugoslavia, elections in post-apartheid South Africa. On joining the BBC in 1995, Afghanistan, Latin America, the Middle East and Africa fell within his investigative orbit. To his list of employers could also be added Reuters, CNN and Al Jazeera English.

During his tenure with Al Jazeera, for a time one of the funkiest outfits on the media scene, Greste was arrested along with two colleagues in Egypt accused of aiding the Muslim Brotherhood. He spent 400 days in jail before deportation. Prison in Egypt gave him cover, armour and padding for journalistic publicity. It also gave him the smugness of a failed martyr.

Greste then did what many hacks do: become an academic. It is telling about the ailing nature of universities that professorial chairs are being doled out with ease to members of the Fourth Estate, a measure that does little to encourage the fierce independence one hopes from either. Such are the temptations of establishment living: you become the very thing you should be suspicious of.

With little wonder, Greste soon began exhibiting the symptoms of establishment fever, lecturing the world as UNESCO Chair of Journalism and Communication at the University of Queensland on what he thought journalism ought to be. Hubris struck. Like so many of his craft, he exuded envy at WikiLeaks and its gold reserves of classified information. He derided its founder, Julian Assange, for not being a journalist. This was stunningly petty, schoolyard scrapping in the wake of the publisher’s forced exit from the Ecuadorian Embassy in London in 2019. It ignored that most obvious point: journalism, especially when it documents power and its abuses, thrives or dies on leaks and often illegal disclosures.

It is for this reason that Assange was convicted under the US Espionage Act of 1917, intended as a warning to all who dare publish and discuss national security documents of the United States.

In June this year, while celebrating Assange’s release (“a man who has suffered enormously for exposing the truth of abuses of power”) evidence of that ongoing fixation remained. Lazily avoiding the redaction efforts that WikiLeaks had used prior to Cablegate, Greste still felt that WikiLeaks had not met that standard of journalism that “comes with it the responsibility to process and present information in line with a set of ethical and professional standards.” It had released “raw, unredacted and unprocessed information online,” thereby posing “enormous risks for people in the field, including sources.”

It was precisely this very same view that formed the US prosecution case against Assange. Greste might have at least acknowledged that not one single study examining the effects of WikiLeaks’ disclosures, a point also made in the plea-deal itself, found instances where any source or informant for the US was compromised.

Greste now wishes, with dictatorial sensibility, to further impress his views on journalism through Journalism Australia, a body he hopes will set “professional” standards for the craft and, problematically, define press freedom in Australia. Journalism Australia Limited was formerly placed on the Australian corporate register in July, listing Greste, lobbyist Peter Wilkinson and executive director of The Ethics Centre, Simon Longstaff, as directors.

Members would be afforded the standing of journalists on paying a registration fee and being assessed. They would also, in theory, be offered the protections under a Media Reform Act (MFA) being proposed by the Alliance for Journalists’ Freedom, where Greste holds the position of Executive Director.

A closer look at the MFA shows its deferential nature to state authorities. As the Alliance for Journalists’ Freedom explains, “The law should not be protecting a particular class of self-appointed individual, but rather the role that journalism plays in our democracy.” So much for independent journalists and those of the Assange-hue, a point well spotted by Mary Kostakidis, no mean journalist herself and not one keen on being straitjacketed by yet another proposed code.

Rather disturbingly, the MFA is intended to aid “law enforcement agencies and the courts identify who is producing journalism”. How will this be done? By showing accreditation – the seal of approval, as it were – from Journalism Australia. In fact, Greste and his crew will go so far as to give the approved journalist a “badge” for authenticity on any published work. How utterly noble of them.

Such a body becomes, in effect, a handmaiden to state power, separating acceptable wheat from rebellious chaff. Even Greste had to admit that two classes of journalist would emerge under this proposal, “in the sense that we’ve got a definition for what we call a member journalist and non-member journalists, but I certainly feel comfortable with the idea of providing upward pressure on people to make sure their work falls on the right side of that line.”

This is a shoddy business that should cause chronic discomfort, and demonstrates, yet again, the moribund nature of the Fourth Estate. Instead of detaching itself from establishment power, Greste and bodies such as the Alliance for Journalists’ Freedom merely wish to clarify the attachment

No comments:

Post a Comment