How do mushrooms become magic?

Research examines why some fungi evolve psychedelic properties

Grant and Award AnnouncementVIDEO: A TIMELAPSE VIDEO OF PSYCHEDELIC AND NON-PSYCHEDELIC FUNGI GROWING IN THE LAB view more

CREDIT: UNIVERSITY OF PLYMOUTH

Psychedelic compounds found in ‘magic mushrooms’ are increasingly being recognised for their potential to treat health conditions such as depression, anxiety, compulsive disorders and addiction.

However, very little is known about how such compounds have evolved and what role they play in the natural world.

To address that, scientists from the University of Plymouth are conducting a first-of-its-kind study using advanced genetic methods and behavioural experiments to address previously untested hypotheses into the origin of psychedelic compounds in fungi.

This includes exploring whether such traits have evolved as a form of defence against fungus-feeding invertebrates, or whether the fungi produce compounds that manipulate insect behaviour for their own advantage.

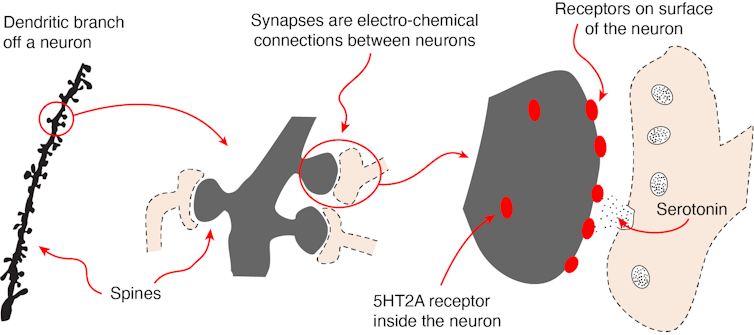

The project will particularly focus on psilocybin, commonly found in so-called ‘magic mushrooms’. In chemical terms, it is very similar to serotonin, which is involved in the sending of information between nerve cells in animals.

The researchers are sampling psychedelic and non-psychedelic fungi, and using next-generation DNA sequencing to test whether or not there is a diverse animal community feeding on psychedelic fungi.

They are also using laboratory tests to investigate fungal-insect interactions, and whether the fungi undergo genetic changes during attack and development. They will also investigate the effect of psilocybin on the growth of soil bacteria.

The research will also involve using cutting-edge gene editing technology to try and create mutant fungi that cannot synthesize psilocybin. It is hoped this will help researchers better understand the role of a wide range of fungal compounds in future.

The study is being led by a team of experienced researchers in molecular ecology, animal-plant interactions and fungal biology in the University’s School of Biological and Marine Sciences. Driving the study are Post-Doctoral Research Fellow Dr Kirsty Matthews Nicholass and Research Assistant Ms Ilona Flis.

Dr Jon Ellis, Lecturer in Conservation Genetics, is supervising the study. He said: “In recent years, there has been a resurgence of interest in psychedelic compounds from a human health perspective. However, almost nothing is known about the evolution of these compounds in nature and why fungi should contain neurotransmitter-like compounds is unresolved.

“The hypotheses that have been suggested for their evolution have never been formally tested, and that is what makes our project so ambitious and novel. It could also in future lead to exciting future discoveries, as the development of novel compounds that could be used as fungicides, pesticides, pharmaceuticals and antibiotics is likely to arise from ‘blue-sky’ research investigating fungal defence.”

Dr Kirsty Matthews Nicholass said: “Within Psilocybe alone, there are close to 150 hallucinogenic species distributed across all continents except Antarctica. Yet, the fungal species in which these ‘magic’ compounds occur are not always closely related. This raises interesting questions regarding the ecological pressures that may be acting to maintain the biosynthesis pathway for psilocybin.”

The research is being funded by the Leverhulme Trust and builds on the University’s long-running expertise in novel elements of conservation genetics.

Researchers involved in this project have previously explored the genetic diversity among UK pollinators, the feeding preferences of slugs and snails, and developed an early warning system for plant disease.

Scientists are looking to address untested hypotheses into the

origin of psychedelic compounds in fungi

The researchers have sampled psychedelic and non-psychedelic fungi

from the wild to explore a range of currently untested hypotheses

CREDIT

University of Plymouth

Dr Jon Ellis talks about the history of research into psychedelic compounds in nature

“Fungi generally receive less attention overall than animals and plants, partly because they are less apparent, people interact with them less and they can be hard to study. Historically, there have also been legal barriers which meant certain research has not previously been possible. Saying that, there were some very interesting studies in the 1940s and 50s into the use of LSD as a psychotherapeutic treatment for alcoholism and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Around that time, people also became interested in fungi from an anthropological perspective.

"One couple, the Wassons, went to Mexico and witnessed the ritual use of fungi for the first time in religious ceremonies. Articles they published brought public attention to psychoactive mushrooms. Around this time, there were also other charismatic individuals, such as Timothy Leary, who advocated the use of LSD more widely by the general public. In the 1960s, psychedelic compounds really came to widespread public attention and that ultimately led to governments introducing new laws to restrict their use.

"For some time, that also restricted the fundamental research that could be carried out. More recently, people have returned to that initial research and found that compounds such as psilocybin can have psychotherapeutic benefits. However, that has not addressed their evolution in nature, which is what makes the research we are doing so exciting.

"I hope our project can change the public perception of magic mushrooms. But beyond that, asking questions about the biological world is a fundamental part of our human nature and this project fits into a long narrative of research asking questions about biodiversity and its evolution.”