Erika Dyck,

Sun, January 15, 2023

Psychedelics are being held up as a potential solution to the growing need for mental health treatment. But, magic mushrooms are not magic bullets.

Patients in Alberta will now be able to legally consider adding psychedelic-assisted therapy to the list of treatment options available for mental illnesses.

Alberta psychiatrists and policymakers suggest that they are getting ahead of the curve by creating regulations to ensure the safe use of these hallucinogenic substances in a therapeutically supported environment. As of Jan. 16, the option is available only through registered and licensed psychiatrists in the province.

Alberta’s new policy may set a precedent that moves Canadians one step closer to accepting psychedelics as medicinal substances, but historically these drugs were widely sought out for recreational and non-clinical purposes. And, if cannabis has taught us anything, medicalizing may simply be a short stop before decriminalizing and commercializing.

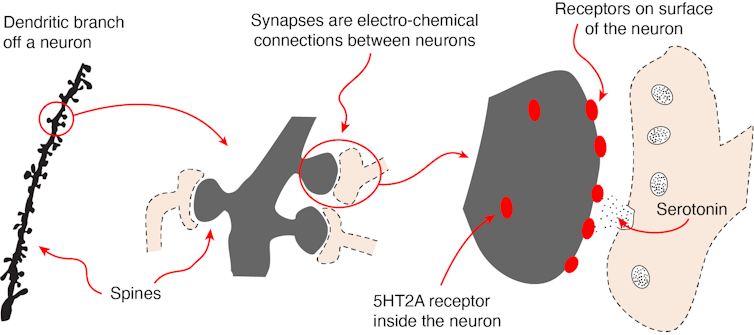

Psychedelic drugs — including LSD, psilocybin (magic mushrooms), MDMA (ecstasy) and DMT (ayahuasca) — are criminalized substances in most jurisdictions around the world, but some people are suggesting it is time to re-imagine them as medicines. A few places are even considering decriminalizing psychedelics altogether, claiming that naturally occurring plants like mushrooms, even “magic” ones, should not be subject to legal restrictions.

In the wake of cannabis reforms, it appears that psychedelics may be the next target in the dismantling of the war on drugs. Canada made bold strides internationally with its widespread cannabis decriminalization, but are Canadians ready to lead the psychedelic renaissance?

Early psychedelic research

There is some precedent for taking the lead. In the 1950s and ‘60s, an earlier generation of researchers pioneered the first wave of psychedelic science, including Canadian-based psychiatrists who coined the word psychedelic and made headlines for dramatic breakthroughs using LSD to treat alcoholism.

Vancouver-based therapists also used LSD and psilocybin mushrooms to treat depression and homosexuality. While homosexuality was considered both illegal and a mental disorder until later in the 1970s, psychedelic therapists pushed back against these labels as patients treated for same-sex attraction more often experienced feelings of acceptance — reactions that aligned this particular approach in Vancouver with the gay rights movement.

Despite positive reports of clinical benefits, by the end of the 1960s psychedelics had earned a reputation for recreational use and clinical abuse. And, there was good reason to draw these connections, as psychedelic drugs had moved from pharmaceutical experimentation into mainstream culture, and some researchers had come under scrutiny for unethical practices.

Regulation and criminalization

Most legal psychedelics ground to a halt in the 1970s with a set of regulatory prohibitions and cultural backlash. In public health reports since the 1970s, psychedelics have been described as objects of unethical research, recreational abuse and personal risk including injury and even death.

Underground chemists and consumers tried to combat this image, suggesting that psychedelics provided intellectual and spiritual insights and enhanced creativity.

Most jurisdictions around the world criminalized psychedelics, whether for clinical research or personal experimentation. Indigenous and non-western uses of hallucinogenic plants of course stretch back even further in history, and these too came under legal scrutiny through a combination of colonial pressures to assimilate and a looming war on drugs that did not distinguish between religious practices and drug-seeking behaviours.

The return of psychedelics

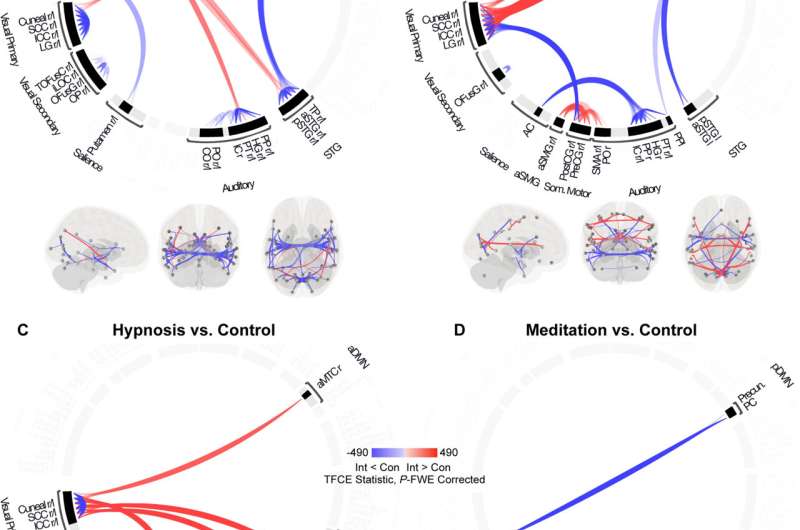

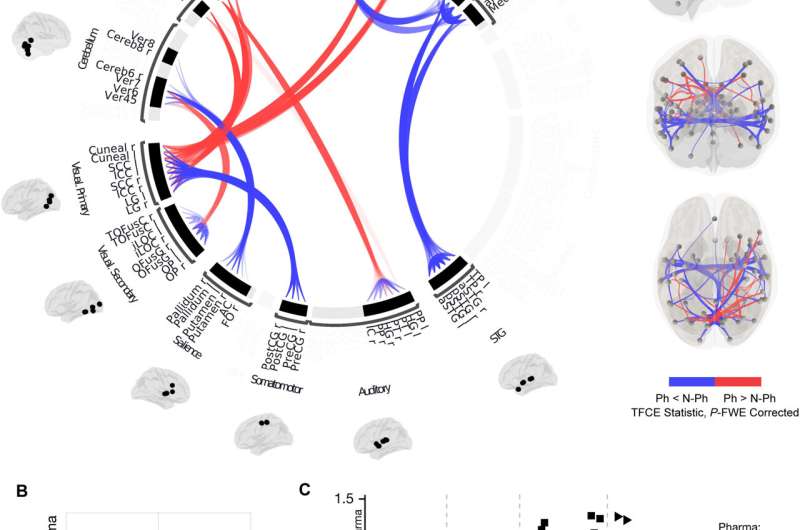

At the moment, the next generation of scientific research on psychedelics still lags behind the popular enthusiasm that has catapulted these substances into the mainstream.

In the last decade, regulations prohibiting psychedelics have started relaxing. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has designated breakthrough therapy status to MDMA and psilocybin, based on their performance in clinical trials with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and treatment-resistant depression, respectively.

Health Canada has provided exemptions for the use of psilocybin for patients with end-of-life anxiety, and has started approving suppliers and therapists interested in working with psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy. Training programs for psychedelic therapists are popping up across Canada, perhaps anticipating a change in regulation and the current lack of trained professionals ready to deliver psychedelic medicine.

At the moment, the next generation of scientific research on psychedelics still lags behind the popular enthusiasm that has catapulted these substances into the mainstream. Celebrity testimonials and compelling patient accounts are competing for our attention.

Meanwhile, the growing burden of mental illness continues to overwhelm our health-care systems. Psychedelics are being held up as a potential solution. But, magic mushrooms are not magic bullets.

Beyond the medical marketplace

Historically hallucinogenic substances have defied simple categorization as medicines, spiritual enhancers, toxins, sacred substances, rave drugs, etc. Whether or not Health Canada, or the province of Alberta, reclassifies psychedelics as a bona fide therapeutic option, these psychoactive substances will continue to attract consumers outside of clinical settings.

Canada has an opportunity to take the lead once more in this so-called psychedelic renaissance. But, it might be our chance to invest in more sustainable solutions to harm reduction and ways of including Indigenous perspectives, rather than racing to push psychedelics into the medical marketplace.

Indigenous approaches to sacred plants are not only about consuming substances, but involve preparation, intention and integration, often structured in ritualistic settings that are as much about spiritual health as physical or mental health.

This cosmology and approach does not easily fit under the Canada Health Act, nor is it obvious who should be responsible for regulating or administering rituals that sit outside of our health-care system. These differences in how we might imagine the value of psychedelics is an opportunity to rethink the place of Indigenous knowledge in health systems.

We are well positioned to take a sober approach to the psychedelic hype, which has been driven in large part by financial interests, and consider what aspects of the psychedelic experience we want to preserve.

Now may be a good time to reinvest in our public institutions to ensure that psychedelics don’t simply become another pharmaceutical option that profits private investors. Instead, we have an opportunity with psychedelics to rethink how a war on drugs has harmed individuals and communities and how we might want to build a better relationship with pharmaceuticals.

This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent nonprofit news site dedicated to sharing ideas from academic experts. It was written by: Erika Dyck, University of Saskatchewan.

Read more:

The real promise of LSD, MDMA and mushrooms for medical science

Psychedelic experiences disrupt routine thinking — and so has the coronavirus pandemic

Erika Dyck receives funding from Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council. She is a board member of the US not-for-profit Chacruna Institute for Psychedelic Plant Medicines.