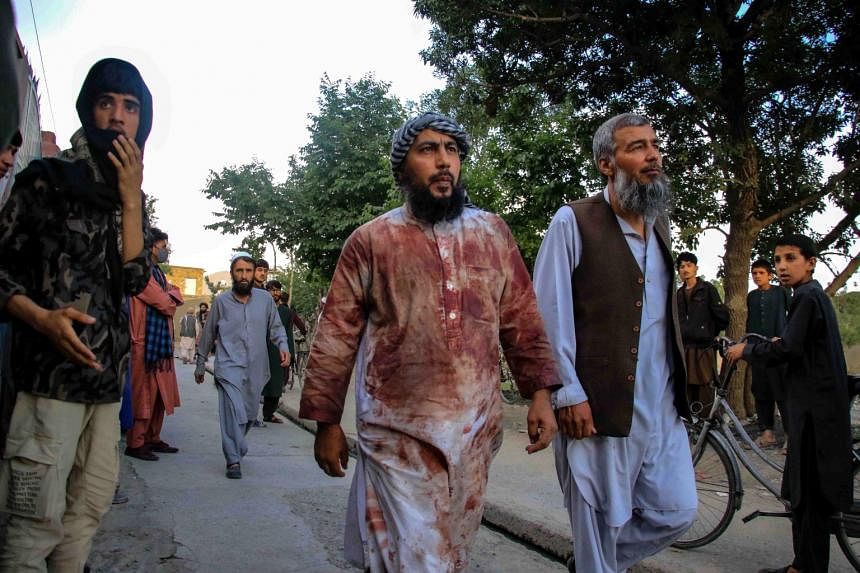

KABUL (NYTIMES) - The first blast ripped through a school in Kabul, the Afghan capital, killing high school students. Days later, explosions destroyed two mosques and a minibus in the north of the country. The following week, three more explosions targeted Shi'ite and Sufi Muslims.

The attacks of the past two weeks have left at least 100 people dead, figures from hospitals suggest, and stoked fears that Afghanistan is heading into a violent spring, as the Islamic State's affiliate in the country tries to undermine the Taliban government and assert its newfound reach.

The sudden spate of attacks across the country has upended the relative calm that followed the Taliban's seizing of power in August, which ended 20 years of war. And by targeting civilians - the Hazara Shi'ite, an ethnic minority, and Sufis, who practise a mystical form of Islam, in recent weeks - they have stirred dread that the country may not be able to escape a long cycle of violence.

The Islamic State affiliate in Afghanistan - known as Islamic State Khorasan - has claimed responsibility for four of the seven recent major attacks, according to SITE Intelligence Group, which tracks extremist organisations. Those that remain unclaimed fit the profile of previous attacks by the group, which considers Shi'ites and Sufis heretics.

With the attacks, the Islamic State group's Afghanistan affiliate has undercut the Taliban's claim that they had extinguished any threat from the Islamic State in the country. It has also reinforced concerns about a potential resurgence of extremist groups in Afghanistan that could eventually pose an international threat.

Last month the Islamic State claimed it had fired rockets into Uzbekistan from northern Afghanistan - the first such purported attack by the group on a Central Asian nation.

"ISIS-K is resilient; it survived years of airstrikes from Nato forces and ground operations from the Taliban during its insurgency," said Mr Michael Kugelman, deputy director of the Asia Programme at the Wilson Centre, a think tank in Washington, using an alternate name for the Islamic State Khorasan.

"Now after the Taliban takeover and the US departure, ISIS-K has emerged even stronger."

The Islamic State group's Afghanistan affiliate was established in 2015 by disaffected Pakistani Taliban fighters. The group's ideology took hold partly because many villages there are home to Salafi Muslims, the same branch of Sunni Islam as the Islamic State. Salafists are a smaller minority among the Taliban, who mostly follow the Hanafi school.

Since its founding, the Islamic State group's Afghanistan affiliate has been antagonistic toward the Taliban: At times the two groups have fought for turf, and last year Islamic State leaders denounced the Taliban's takeover of Afghanistan, saying that the group's version of Islamic rule was insufficiently hard line.

Still, for most of the past six years the Islamic State has been contained to eastern Afghanistan amid US airstrikes and Afghan commando raids that killed many of its leaders. But since the Taliban seized power, the Islamic State has grown in reach and expanded to nearly all 34 provinces, according to the United Nations Mission in Afghanistan.

After the Taliban broke open prisons across the country during their military advance in the summer, the number of Islamic State fighters in Afghanistan doubled to nearly 4,000, the UN found.

The group also ramped up its activity across the country, said Mr Abdul Sayed, a security specialist and researcher who tracks the Islamic State group's Afghanistan affiliate and other radical groups. In the last four months of 2021, the Islamic State carried out 119 attacks in Afghanistan, up from 39 during the same period a year earlier. They included suicide bombings, assassinations and ambushes on security checkpoints.

Of those, 96 targeted Taliban officials or security forces, compared with only two in the same period in 2020 - a marked shift from earlier last year when the group primarily targeted civilians, including activists and journalists.

In response, the Taliban carried out a brutal campaign last year against suspected Islamic State fighters in the eastern province of Nangarhar. Their approach relied heavily on extrajudicial detentions and killings of those suspected of belonging to the Islamic State, according to local residents, analysts and human rights monitors.

For months this past winter, attacks by the Islamic State dwindled - raising some hope that the Taliban's campaign was proving effective. But the recent spate of high-profile attacks that have claimed many civilian lives suggests that the Islamic State used the winter to regroup for a spring offensive - a pattern perfected by the Taliban when it was an insurgency.

While the Islamic State group's Afghanistan affiliate does not appear to be trying to seize territory, as the Islamic State did in Iraq and Syria, the attacks have demonstrated the group's ability to sow violent chaos despite the Taliban's heavy-handed tactics, analysts say.

They have also stoked concerns that, sensing perceived weakness in the Taliban government, other extremist groups in the region that already have reason to resent the Taliban may shift alliances to the Islamic State.

"ISIS-K wants to show its breadth and reach beyond Afghanistan, that its jihad is more violent than that of the Taliban, and that it is a purer organisation that doesn't compromise on who is righteous and who isn't," said Dr Asfandyar Mir, a senior expert at the United States Institute of Peace.

The blasts have particularly rattled the country's Hazara Shi'ites, who have long feared that the Taliban - which persecuted Afghan Shi'ites for decades - would allow violence against them to go unchecked. The strife has also caused concern in neighbouring Iran, a Shi'ite theocracy.

Many Afghan Shi'ites have been on edge since suicide bombings by the Islamic State at Shi'ite mosques in one northern and one southern city together killed more than 90 people in October. The recent blasts, which mainly targeted areas dominated by Hazara communities, deepened those fears.

Late last month, Mr Saeed Mohammad Agha Husseini, 21, was standing outside his home in the Dasht-e-Barchi area of Kabul, a Hazara-dominated area, when he felt the thud of an explosion. He and his father raced to the school down the street, where throngs of terrified students poured out its gate, the bloodied bodies of some of their classmates sprawled across the pavement.

His father rushed to help the victims, but minutes later Mr Husseini heard another deafening boom. A second explosion hit the school's gate, fatally wounding his father.

A week later, Mr Husseini sat under the shade of a small awning with his relatives to mourn. Outside, their once-bustling street was quiet, the fear of another explosion still ripe. At the school, community leaders had been discussing hiring guards to take security into their own hands.

"The government cannot protect us; we are not safe," Mr Husseini said. "We have to think about ourselves and take care of our security."