CRIMINAL CAPITALI$M

The arrest of Armenian-Russian billionaire Samvel Karapetyan has intensified a very public confrontation between Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan and the Armenian Apostolic Church.

Armenia’s National Security Service (NSS) conducted a search of Karapetyan’s Yerevan residence on June 17, hours after the influential tycoon publicly denounced what he called the government’s “attack” on the church and vowed to intervene if political leaders failed to act.

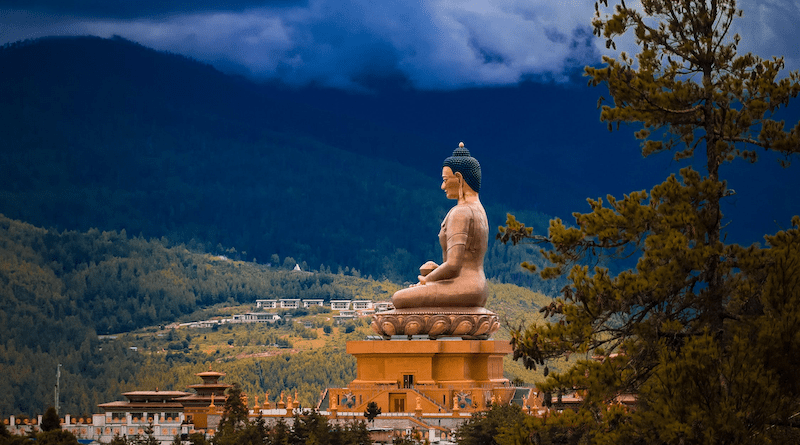

Karapetyan resides in Russia and heads the sprawling Tashir Group, the owner of several major Armenian assets including the Electric Networks of Armenia and Dalma Garden Mall. He is also known for his philanthropic efforts and has long been a key benefactor of the Church, recently funding the renovation of the Etchmiadzin Cathedral, the first cathedral built in Armenia.

“If the politicians fail, then we will participate in our own way,” Karapetyan said outside the cathedral, according to a video published by News.am. “What opinion should I have when a small clique, forgetting Armenian history and the thousands of years of our Church, attacks it?”

Within hours, security agents arrived at his property in what Church officials described as politically motivated retaliation. “The persecution being carried out against Mr. Samvel Karapetyan is yet another manifestation of the Prime Minister’s anti-Church actions, aimed at depriving the Armenian Church of the support of its faithful flock through fear and intimidation,” the Armenian Apostolic Holy Church Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin said in a statement. “We strongly condemn this disgraceful conduct, regarding it as a blow to the reputation and standing of the Republic of Armenia, as well as to the Armenian Church.”

Church-state rift

The arrest follows weeks of public acrimony between Pashinyan and the church, which began when the prime minister used social media to suggest that Catholicos Karekin II, the church’s spiritual leader, had broken his vow of celibacy and fathered a child.

“If it turns out that Karekin II has indeed violated his vow of celibacy and has a child, then he cannot be the Catholicos of all Armenians,” Pashinyan wrote on social media in early June. He claimed the issue represented a threat to both “spiritual security” and “state security”.

The Church responded, accusing Pashinyan of undermining national unity and engaging in a dangerous campaign against one of Armenia’s most revered institutions. “Such actions lead to a split in society, undermine spiritual unity, and weaken the spirit of the nation,” Church leaders said in a statement, though notably did not comment on whether Pashinyan’s claim was true.

Undeterred, Pashinyan continue to repeat the claim in a flood of posts on social media, and called for the Catholicos’s resignation.

His inflammatory language and threats aimed at both clerics and their allies on social media have drawn criticism from broad segments of Armenian society. “Why are the whoremongering ‘clergy’ and their whoremongering ‘benefactors’ suddenly so active?” he said in one post on Facebook, going on to threaten to “neutralise them again. This time, permanently.”

The prime minister also wrote in a Facebook post that it was time to consider nationalising Karapetyan’s Electric Networks of Armenia.

Military defeat

The dispute comes at a politically sensitive time for Pashinyan, whose government has faced persistent criticism following Armenia’s defeat in the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war and the subsequent loss of the ethnic Armenian enclave to Azerbaijan.

This prompted protests during 2024, as Armenians objected to the handover of land to Azerbaijan. Archbishop Bagrat Galstanyan of the Tavush diocese became a key figure in the protests.

In May 2025, Karekin II spoke at a conference in Switzerland, accusing Baku of ethnic cleansing and calling for the right of return for displaced Armenians. His remarks appeared at odds with Pashinyan’s ongoing efforts to normalise ties with Azerbaijan.

Pashinyan is now under pressure on multiple fronts, and the spat with the church is viewed as an attempt to consolidate power and shift the public focus away from Armenia’s military and diplomatic failures.

As well as domestic criticism over his handling of relations with Azerbaijan, internationally relations with Russia have soured, especially as Yerevan made overtures to the EU. Meanwhile, friendly neighbour Iran is now involved in a new war with Israel that threatens to spill over into a border regional conflict.

Pashinyan’s “Real Armenia” ideology, outlined to the population earlier this year, calls for a break with traditional narratives and a focus on economic renewal. He has also sought to focus attention on economic growth and rising living standards in the country, helped by the recent economic boom resulting from Russia’s trade reorientation since its invasion its Ukraine.

Going up against the Armenian Apostolic Church was a gamble for the prime minister. One of the world’s oldest Christian institutions, it has been the nation’s dominant religious body since Armenia became the first country to adopt Christianity as a state religion in the early 4th century.

Despite constitutional guarantees of religious freedom and formal separation of church and state, the Armenian Apostolic Church retains a privileged status and deep social legitimacy. An autumn 2024 poll by the International Republican Institute (IRI) found 84% of the population stated their religion as the Armenian Apostolic Church. A higher proportion of Armenians said they were satisfied with the work of the church than either the prime minister’s office or government ministries — though the share of those satisfied has dropped since 2019.

Still, Armenia’s military defeats and the recent spat with the church — on top of a separate scandal involving Pashinyan’s wife Anna Hakobyan — have been problematic for the Armenian prime minister

The fallout from Karapetyan’s arrest could further inflame the situation. The billionaire’s open challenge to the government and close ties to the church raise the stakes for Pashinyan, who has increasingly portrayed dissenting voices as existential threats to state stability.