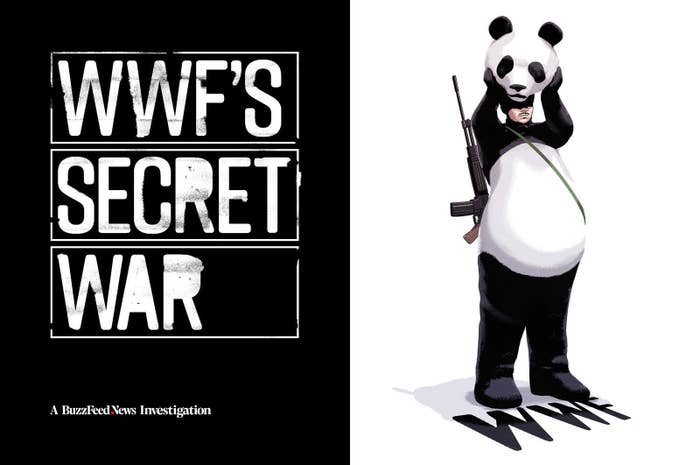

WWF Admitted “Sorrow” Over Human Rights Abuses

A 160-page report, in response to a BuzzFeed News investigation, found long-standing failures at the celebrated wildlife charity.

Katie J.M. Baker BuzzFeed News Investigative Reporter

Posted on November 25, 2020

Tim Lane / BuzzFeed News

Read the original March 2019 BuzzFeed News investigation.

One of the world’s largest charities knew for years that it was funding alleged human rights abusers but repeatedly failed to address the issue, a lengthy, long-delayed report revealed on Tuesday.

A BuzzFeed News investigation first exposed in March 2019 how WWF, the beloved nonprofit with the cuddly panda logo, financed and equipped park rangers accused of beating, torturing, sexually assaulting, and murdering scores of people. In response, WWF immediately commissioned an “independent review” led by Navi Pillay, a former United Nations commissioner for human rights.

The 160-page review, which has now been published online, corroborates problems exposed by BuzzFeed News in Nepal, Cameroon, the Republic of the Congo, and the Democratic Republic of Congo. The report claimed the panel was prevented by the COVID-19 pandemic from traveling to locations where the abuses reportedly took place.

The review found that WWF had failed again and again to follow “its own commitments to respect human rights” — commitments that are not just required by law but essential to “the conservation of nature.”

In a statement issued in response to the review, WWF expressed “deep and unreserved sorrow for those who have suffered,” and said that abuses by park rangers “horrify us and go against all the values for which we stand.” The charity acknowledged its shortcomings and welcomed the recommendations, saying “we can and will do more.”

Pillay’s review declined to address whether high-level executives, who BuzzFeed News found were aware of “accelerating” violence at at least one wildlife park as early as January 2018, were responsible for the charity’s missteps.

In the Congo Basin, where WWF did an “especially weak” job fulfilling its human rights commitments, the wildlife charity did not fully investigate accounts of murder, rape, and torture out of fear that government partners would “react negatively to an effort to investigate past human rights abuses,” the panel found. There and elsewhere, WWF provided technical and financial support to park rangers, known locally as “eco-guards,” even after learning about similar, horrifying allegations — and, in some cases, after damning reviews commissioned by the non-profit itself confirmed “serious and widespread” reports of abuse.

The report found “no formal mechanism in place for WWF to be informed of alleged abuses during anti-poaching missions” in Nepal, despite torture, rape, and murder allegations ranging from the early 2000s to this past July, when park officials were alleged to have beaten an Indigenous youth and destroyed homes of a local community. “WWF needs to know what is happening on the ground where it works” in order to fulfill its own human rights policies, the report said.

Frank Bienewald / Getty Images

A river in Nepal's Chitwan National Park.

Overall, WWF paid too little attention to credible abuse allegations, failed to construct a system for victims to make complaints, and painted an overly rosy picture of its anti-poaching war in public communications, the report found. "Unfortunately, WWF’s commitments to implement its social policies have not been adequately and consistently followed through,” the report’s authors wrote.

WWF has supported efforts to fight wildlife crime for decades. Although local governments officially employ and pay park rangers who patrol national parks and protected wildlife reserves, in a number of countries across Africa and Asia WWF has provided crucial funding to make their jobs possible. The charity has framed its crusade against poaching in the hardened terms of war.

In a multipart series, BuzzFeed News found that WWF’s war on poaching came with civilian casualties: impoverished villagers living near the parks. At the time, WWF responded that many of BuzzFeed’s assertions did “not match our understanding of events” — yet the charity swiftly overhauled many of its human rights policies after publication.

In the US, the series spurred a bipartisan investigation and proposed legislation that would prohibit the government from awarding money to international conservation groups that fund or support human rights violations. It also prompted a freeze of funds by the Interior Department, a review by the Government Accountability Office, and separate government probes in the UK and Germany.

The new review offers more recommendations for the charity to improve its oversight, including hiring more human rights specialists, conducting stronger due diligence before committing to conservation projects, signing human rights commitments with WWF’s government and law enforcement partners in the field, and establishing effective complaint systems so that Indigenous people can more easily report abuse.

The review found that there was no “consistent and unified effort” across WWF’s network of offices around the world to “address complaints about human rights abuses” until 2018.

Many of the panel’s findings pointed directly to the top: “Commitments to meet the responsibility to respect human rights should be approved at the most senior level of the institution,” the panel wrote. Although all of WWF’s offices in the Congo Basin fall under the direct authority of WWF International, staff at its headquarters in Gland, Switzerland did little to oversee the organization’s work there.

WWF International also didn’t provide clear guidance to local offices about how to implement its human rights commitments. For example, there were no network-wide norms about how to work with law enforcement and park rangers. As a result, each program office “was left on its own to develop – or not – codes of conduct, training materials, conditions for supporting rangers, and procedures for responding to allegations of abuse.”

“Ultimately, the responsibility was on WWF International and the WWF Network as a whole to ensure that the allegations of human rights abuses by eco-guards to which WWF was providing financial and technical support were properly addressed,” the panel wrote.

Ezequiel Becerra / Getty Images

WWF International Director General Marco Lambertini

Last October BuzzFeed News revealed that both Director General Marco Lambertini and Chief Operating Officer Dominic O’Neill personally reviewed a WWF-commissioned report documenting “accelerating” accounts of violence by WWF-backed guards in Cameroon. That report was sent to higher-ups in January 2018 — more than a year before BuzzFeed News began exposing similar abuses. Yet Pillay’s review said little about whether WWF executives were responsible for the charity’s failings.

Instead the review focused on WWF’s complex system, under which individual program offices partner with countries “with apparently very limited consultation or oversight from WWF International,” even when WWF International is legally responsible. This obscured “clear lines of responsibility and accountability,” resulting in “difficulties and confusion” and “ineffective” attempts to address human rights, the panel wrote.

The panel couldn’t find a single contract between WWF International and its partner countries that contained provisions concerning human rights responsibilities or the rights of Indigenous people.

The panel also criticized WWF’s press briefings at length, saying it needed to be “more forthcoming about the challenges it faces” and “more transparent about how it responds when faced with allegations of human rights abuses associated with activities that it supports.” In some cases, “it is clear that to avoid fuelling criticism WWF decided not to publish commissioned reports, to downplay information received, or to overstate the effectiveness of its proposed responses.”

An internal focus on promoting “good news” seems “to have led to a culture” in which program offices “have been unwilling to share or escalate the full extent of their knowledge about allegations of human rights abuses because of concern about scaring off donors or offending state partners,” the report said. “WWF at all levels should be more transparent both internally and externally about the challenges it faces in promoting conservation and respecting human rights. Equally important, it must be more forthright about the effectiveness, or lack of effectiveness, of its efforts to overcome those challenges.”

The report attracted immediate criticism from prominent voices who said it did not fully acknowledge the charity’s responsibility for abuses against Indigenous people. Stephen Corry, the director of Survival International, the tribal rights advocacy group, said “the report echoes previous WWF responses in passing the blame onto ‘government rangers.’” A spokesperson for Rainforest Foundation UK said the report “fails to take responsibility” for WWF’s shortcomings “or issue a sincere apology to the many individuals who have suffered human rights abuses carried out in their name.”

The Forest Peoples Program, an Indigenous rights group that has reported abuses to WWF, said the report showed the need for all wildlife charities to take a hard look at themselves.

“The human rights abuses suffered by Indigenous peoples and local communities listed in the report highlight fundamental issues that arise across the conservation sector as a whole, not isolated to WWF,” said Helen Tugendhat, program coordinator at the Forest Peoples Program. “We urge other conservation organizations as well as conservation funders to read this report closely and evaluate and amend their own practices.”

WWF Funds Guards Who Have Tortured And Killed People Tom Warren · March 4, 2019

Katie Baker is an investigative reporter for BuzzFeed News and is based in London.

Tom Warren is an investigations correspondent for BuzzFeed News and is based in London.