A Pregnant Ancient Egyptian Mummy Has Been Discovered in a Shocking World First

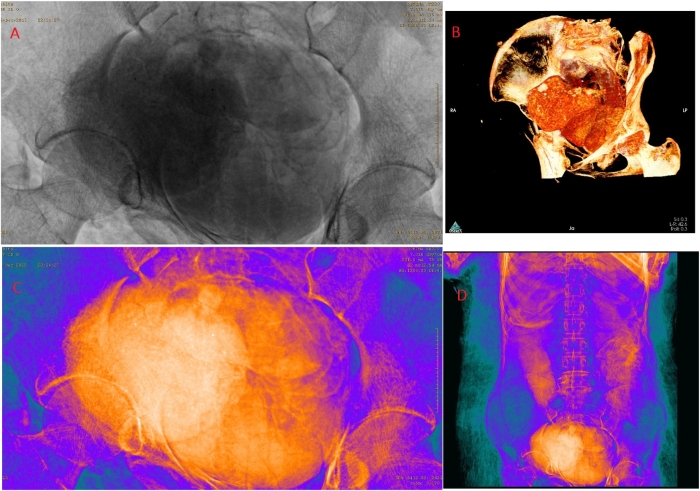

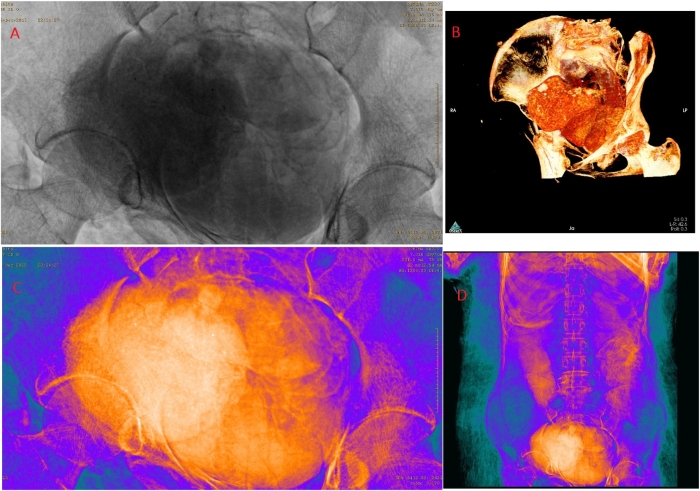

Photo and scans of the mummy. (Ejsmond et al., J. Archaeol. Sci., 2021)

MICHELLE STARR

30 APRIL 2021

At first, archaeologists thought they were scanning the mummy of an ancient Egyptian priest named Hor-Djehuty. Then, in the body's abdomen, images revealed what appeared to be the bones of a tiny foot.

Full scans confirmed it: the foot belonged to a tiny fetus, still in the womb of its deceased and mummified mother.

Not only is this the first time a deliberately mummified pregnant woman has been found, it presents a fascinating mystery. Who was the woman? And why was she mummified with her fetus? So peculiar is the discovery, scientists have named her the Mysterious Lady of the National Museum in Warsaw.

"For unknown reasons, the fetus had not been removed from the abdomen during the mummification," archaeologist Wojciech Ejsmond of the Polish Academy of Sciences told Science in Poland.

"For this reason, the mummy is really unique. Our mummy is the only one identified so far in the world with a fetus in the womb."

The mummy and its sarcophagus were donated to the University of Warsaw in 1826 and kept in the National Museum in Warsaw, Poland since 1917. The artifact actually has an interesting history. The mummy was initially thought to be female, likely because of the elaborate sarcophagus.

The coffin, cartonnage case, and mummy. (National Museum in Warsaw, Warsaw Mummy Project)

It wasn't until around 1920 when the name on the coffin and cartonnage was translated that perception shifted. The writing revealed that the interred was named Hor-Djehuty, and was highly placed.

"Scribe, priest of Horus-Thoth worshiped as a visiting deity in the Mount of Djeme, royal governor of the town of Petmiten, Hor-Djehuty, justified by voice, son of Padiamonemipet and lady of a house Tanetmin," the translation read.

In 2016, however, computer tomography revealed that the mummy in the sarcophagus may not have actually been Hor-Djehuty. The bones were too delicate, male reproductive organs were missing, and a three-dimensional reconstruction revealed breasts.

Given that artifacts weren't exactly handled with the best care in the 19th century, and given that the coffin and cartonnage were indeed made for a male mummy, it seems that an entirely different mummy was placed in the sarcophagus at some point - perhaps to be passed off as a more valuable artifact.

This is supported by damage to some of the mummy's bandages - likely caused by 19th century looters rifling through looking for amulets, the researchers said.

Thus, it's impossible to know who exactly the woman was, or even if she came from Thebes where the coffin was found; however, a few facts can be gauged from her remains.

Firstly, she was mummified with great care, and with a rich set of amulets, suggesting in and of itself that she was someone important - mummification was a luxury in ancient Egypt, unavailable to most.

It wasn't until around 1920 when the name on the coffin and cartonnage was translated that perception shifted. The writing revealed that the interred was named Hor-Djehuty, and was highly placed.

"Scribe, priest of Horus-Thoth worshiped as a visiting deity in the Mount of Djeme, royal governor of the town of Petmiten, Hor-Djehuty, justified by voice, son of Padiamonemipet and lady of a house Tanetmin," the translation read.

In 2016, however, computer tomography revealed that the mummy in the sarcophagus may not have actually been Hor-Djehuty. The bones were too delicate, male reproductive organs were missing, and a three-dimensional reconstruction revealed breasts.

Given that artifacts weren't exactly handled with the best care in the 19th century, and given that the coffin and cartonnage were indeed made for a male mummy, it seems that an entirely different mummy was placed in the sarcophagus at some point - perhaps to be passed off as a more valuable artifact.

This is supported by damage to some of the mummy's bandages - likely caused by 19th century looters rifling through looking for amulets, the researchers said.

Thus, it's impossible to know who exactly the woman was, or even if she came from Thebes where the coffin was found; however, a few facts can be gauged from her remains.

Firstly, she was mummified with great care, and with a rich set of amulets, suggesting in and of itself that she was someone important - mummification was a luxury in ancient Egypt, unavailable to most.

X-ray and CT scans of the mummy's abdomen, revealing the fetus. (Ejsmond et al., J. Archaeol. Sci., 2021)

She died just over 2,000 years ago, in approximately the first century BCE, between the ages of 20 and 30, and the development of the fetus suggests she was between 26 and 30 weeks pregnant.

As the first-ever discovery of a pregnant embalmed mummy, the Mysterious Lady poses fascinating questions about ancient Egyptian spiritual beliefs, the researchers said. Did the ancient Egyptians believe that unborn fetuses could go on to the afterlife, or was this mummy a strange anomaly?

It's unclear how she died, but the team believes that analysis of the mummy's preserved soft tissues might yield some clues.

"High mortality during pregnancy and childbirth in those times is not a secret," Ejsmond said. "Therefore, we believe that pregnancy could somehow contribute to the death of the young woman."

The team's research has been published in the Journal of Archaeological Science.

She died just over 2,000 years ago, in approximately the first century BCE, between the ages of 20 and 30, and the development of the fetus suggests she was between 26 and 30 weeks pregnant.

As the first-ever discovery of a pregnant embalmed mummy, the Mysterious Lady poses fascinating questions about ancient Egyptian spiritual beliefs, the researchers said. Did the ancient Egyptians believe that unborn fetuses could go on to the afterlife, or was this mummy a strange anomaly?

It's unclear how she died, but the team believes that analysis of the mummy's preserved soft tissues might yield some clues.

"High mortality during pregnancy and childbirth in those times is not a secret," Ejsmond said. "Therefore, we believe that pregnancy could somehow contribute to the death of the young woman."

The team's research has been published in the Journal of Archaeological Science.