Capitalists will be ‘emboldened’ if she loses recall battle, Seattle’s Kshama Sawant tells Andrew Buncombe

Thursday 24 June 2021

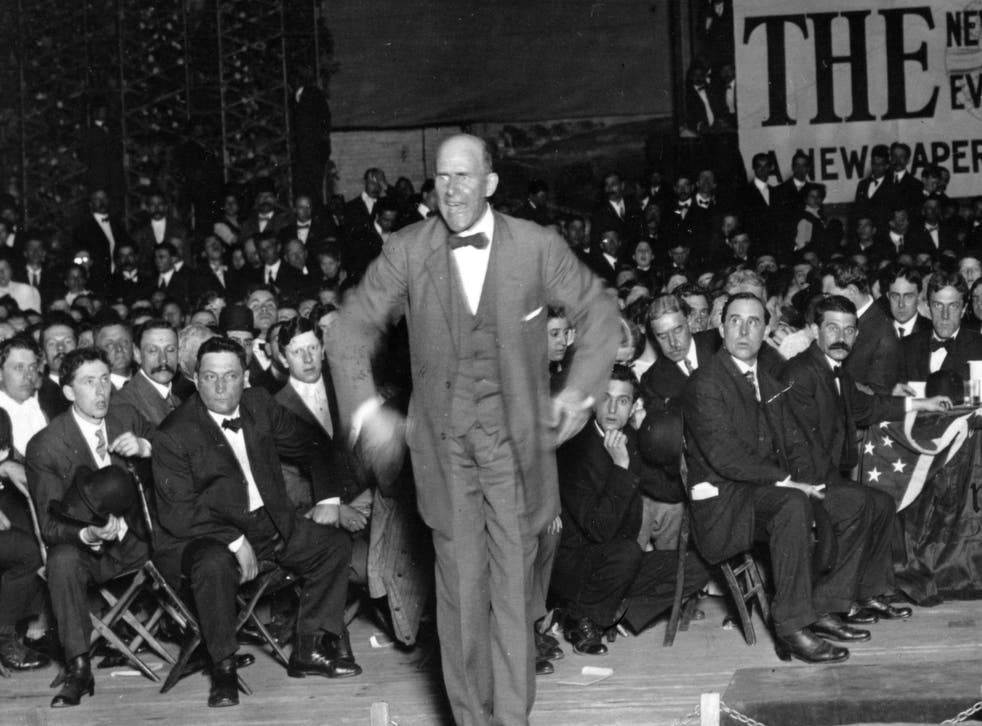

The former software engineer was first elected to Seattle City Council in 2013

(Getty)

Put in her own words, what is happening amounts to one of the “worst attacks on America’s left in decades”. It is perhaps not quite as high profile or significant as the 2016 undertaking by the Democratic establishment to undermine the presidential campaign of Bernie Sanders. But it is similar, “a full frontal assault on the idea that the working class can fight back”.

Furthermore, warns Kshama Sawant, if her opponents are successful, then “the right wing and the ruling class and the capitalists will be even more emboldened to carry out further attacks on the left”.

We are sitting outside a coffee shop in Seattle’s Central District, and the warm afternoon air is suddenly peppered with the language of Marxist rebellion – of elites and workers, of unions and rights, of people coming together and fighting for a revolution

Sawant, 47, represents ward three on Seattle City Council and, as a member of the Socialist Alternative party, is by many assessments the most long-serving and highest-profile socialist politician in the country.

Buffalo is on the cusp of electing its first socialist, female mayor

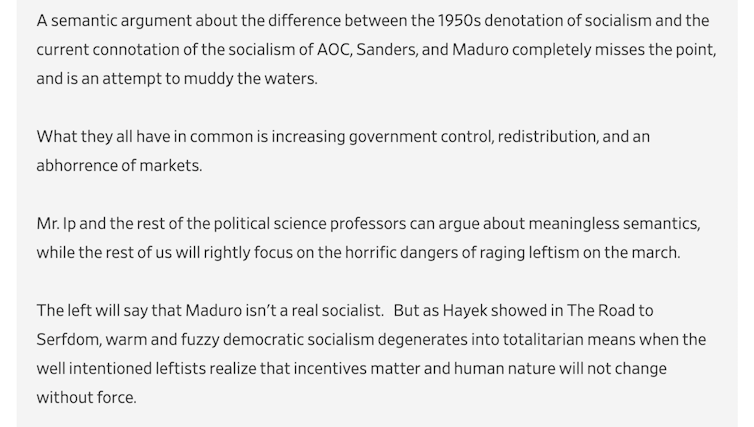

While Sanders, 79, and the likes of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, 31, may support some socialist policies, both campaigned for the Democratic Party, which despite the wild-eyed claims of Donald Trump and some other Republicans, is not a socialist organisation. (Sanders remains an independent, though he invariably votes with the Democrats.)

By contrast, Sawant’s Socialist Alternative describes itself as Marxist, and seeks to create a mass workers movement that would support free health care and education and lead an “international struggle against the failed system” of capitalism.

Yet, Sawant’s time may be up. The threat she has been talking about is an an attempt to oust her from the council by means of a so-called recall election.

In essence, if her opponents manage to collect the signatures of a little more than 10,000 residents of ward three, an election will be held in which her constituents will be asked if they want to hold onto her as their council member, or have her replaced.

Sawant and her supporters claim the recall is an undemocratic undertaking, backed and supported by “millionaires and billionaires” angered by her pro-working class agenda. Those behind the recall allege Sawant broke the law last summer, during the protests for racial justice that swept the country after the murder of George Floyd.

In particular they allege she improperly opened the buildings of the council chamber to host 1,000 protesters during a Covid lockdown, and led demonstrators to the home of the city’s mayor, Jenny Durkan, where she had called for her impeachment.

]

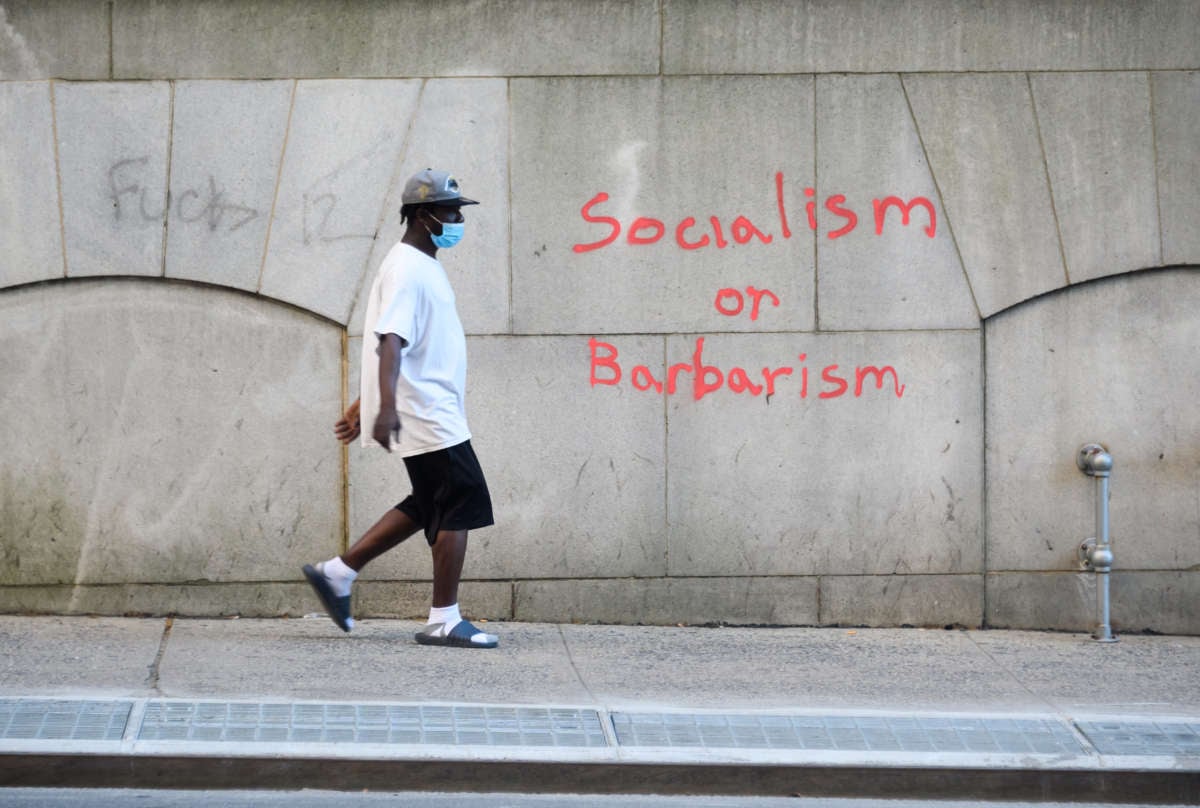

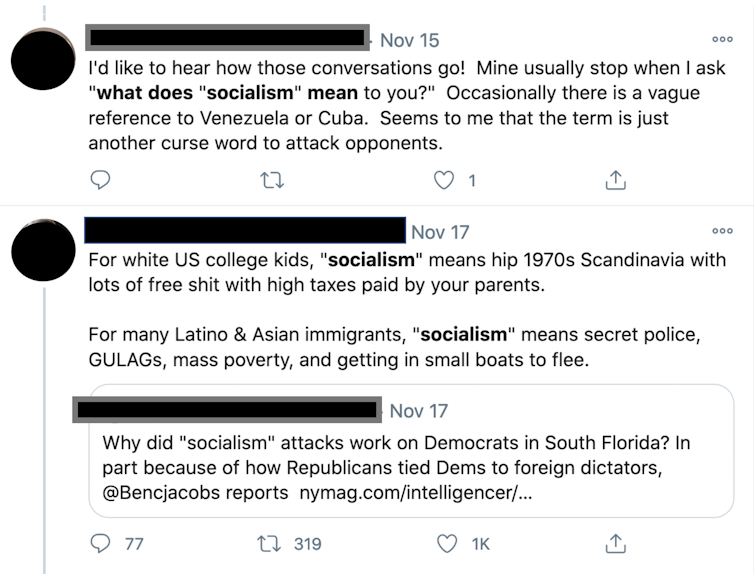

Signs for and against the recall are popping up in Seattle’s ward three

(Andrew Buncombe)

Durkan had for several years demanded to keep her address confidential, and out of the public record, citing safety issues because of her previous work as a senior federal prosecutor. “We demand action now,” Sawant had said outside Durkan’s home.

In the days that followed, Durkan accused Sawant of putting people’s safety at risk, and called for her to be to be kicked from the council.

Sawant defended her actions, saying: “This is an attack on working people’s movements, and everything we are fighting for, by a corporate politician desperately looking to distract from her failures of leadership and politically bankrupt administration.”

When Sawant was first elected in 2013, she was the first socialist on the Seattle city council since Anna Louise Strong, a celebrated journalist and activist, won a seat on the school board in 1916. At the time she was the only elected socialist in the nation.

What’s more, the policies she was pushing, in particular for a $15-per hour minimum wage, were out of touch with much of the country.

Barely a decade later, even centrists such as Joe Biden back the “fight for $15”, while younger generation of politicians, including not only Ocasio-Cortez and Rashida Tlaib, but Cori Bush and Janeese Lewis George, have embraced the term “socialism” without fear of an electoral backlash.

This week, India Walton, a socialist and activist, won the Democratic primary to be mayor of Buffalo, and will likely become the first socialist mayor of a major city since 1960.

Police attack protesters with pepper spray in Seattle

All have joined the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), a political organisation rather than a party, even if they are still members of the Democratic Party.

Sawant welcomes no longer being a lone torchbearer.

“[The fact] a lot of elected officials refer to themselves as socialists, I see as an extremely positive development. We showed in 2013, you can be a self-described socialist and that won't be a barrier to you being elected,” she says

“The fact so many socialists have been elected in the United States shows we are in a completely new period – we’re not in the Cold War era anymore. The younger generation has no negative baggage related to socialism. In fact, it's a very positive connotation.”

Sawant pays much credit to Bernie Sanders for never shying away from the word socialist. Yet, she claims the revolution Sanders says the nation needs cannot be secured from working inside the Democratic Party.

“Because at the end of the day, the Democratic Party, while it may have differences with the Republican Party, still represents the interests of Wall Street, of the capitalists,” she says.

Seattle was the first major US city to pass a $15-per hour minimum wage, doing so by a unanimous vote in 2014, a year after Sawant’s election. She won ward three, which includes the Capitol Hill neighbourhood, part of which last summer was ceded to protesters who for a month established a theoretically autonomous zone, known as the Chop (Capitol Hill Occupied Protest), until it was cleared by police.

John Nichols, national affairs correspondent of The Nation, a progressive magazine, credits Sawant with helping ensure such issues as the minimum wage received national attention.

“She broke through in the doldrums of American socialism, before Bernie had run for president, before the DSA had its explosive growth,” says Nichols, author of The S Word: A Short History of an American Tradition – Socialism. “Her victory was a shock, it was a wake up call.”

Nichols says Sawant’s victory had much to do with what was happening in Seattle, a city that was rapidly undergoing the gentrification and economic transformation that has impacted other cities. Her win particularly excited progressives, he says, because of the unabashed nature of her positions, and because she had such “clear politics, [and a] clear set of policies”

.

Henry Bridger II says politicians must be held accountable

(Andrew Buncombe)

In addition to her push for a $15-per hour minimum wage, as a member of the city council Sawant backed a move, known as the head tax, that would have levied a charge on big employers such as Amazon, to fund services for the homeless. The measure was passed, before being repealed after opposition from the business community. (A subsequent version, known as the “JumpStart tax” was later passed.)

In 2019, Amazon controversially threw itself into Seattle city politics, spending $1.5m in support of a number of candidates for the city council it considered “pro-business”, including a challenger to Sawant. Despite its efforts, she was re-elected for a third term.

Sawant, who has been vocal in her opposition to the US’s support of Israel as well as supportive of measures such as rent control and protection against eviction, claims the region’s “corporate elite” is now backing the recall petition in an effort to get rid of her. Among the donors to the recall effort are Doug Herrington, a senior vice president at Amazon, David Stephenson, the chief financial officer at Airbnb, and Jeannie Nordstrom, a member of a department store empire, though the maximum any business or person can contribute by law is $1,000. (The Airbnb official donated just $150, records suggest, while Herrington and Nordstrom gave $1,000.)

Sawant claims her donors, by contrast, are baristas, teachers, and healthcare workers, the “whole gamut of the working class”.

“I don’t have a crystal ball,” she adds. “But I will tell you exactly what is going to happen if the recall succeeds – there will be a stunning attempt to roll back many of the victories we have won. But more than that, it will be a chilling effect on social movements.”

Airbnb had no comment about its CFO’s contribution, a Nordstrom spokesperson also declined to comment, while an Amazon spokesperson, Glenn Kuper, asked about Herrington’s donation, said: “As engaged residents and voters, our employees are welcome to support or oppose any issue or candidate they wish to in their personal capacity.”

Henry Bridger II is chair of the Recall Sawant campaign. A longtime Seattle resident, he says he voted for Sawant in 2013, though has not done so since.]

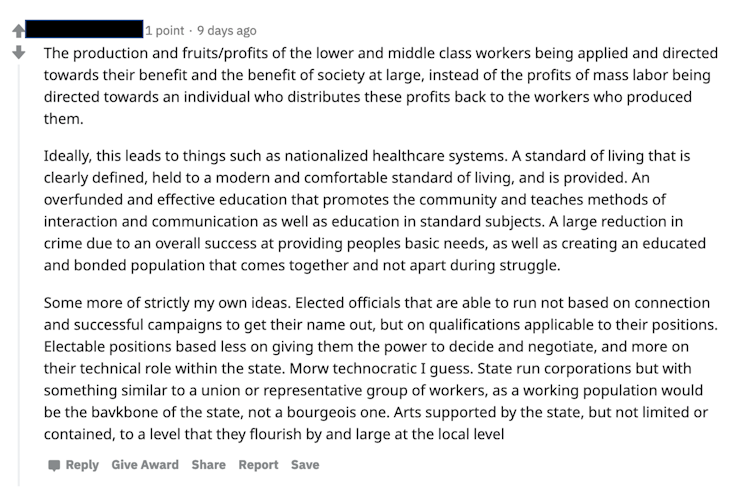

Sawant joined protesters outside a Seattle police station during last year’s racial justice demonstrations

(Getty)

He claims, however, the effort to recall Sawant is not driven by any political differences he and others may have with her, but that she broke the law. The recall campaign alleges that in addition to leading a march to the mayor’s house and hosting a protest inside city hall, in early 2020 she misused city council resources to push a ballot initiative.

(Sawant has claimed she did nothing wrong in regard to any of the allegations. However, in May she admitted misusing official resources for a ballot measure before a city ethics commission. At the time she said she “did not wilfully disregard any ethics rules”.)

Bridger insists the allegations levelled at Sawant are serious issues, and says the campaign is supported by a broad swathe of voters. He rejects assertions it is being backed by millionaires and billionaires.

“I care about any politician who breaks the law. I really do, because they impact us,” he says. “She broke the law, and we’ve already seen what happened with Trump, and how nothing sticks … It has to be done. Somebody has to step up.”

Does he equate Sawant’s alleged actions with Trump’s actions ahead of the 6 January storming of the US Capitol by his supporters?

“Absolutely. It’s the same thing,” he says. “At city hall, she endangered employees who were there by bringing in hundreds of people in the middle of a pandemic. You don’t do that, you don’t break the law, just because you feel doing it is going to get you what you want.”

Bridger, 55, who is currently unemployed, says the campaign is already more than halfway to reaching the 10,739 signatures it needs, a figure that represents 25 per cent of the total votes votes for the seat in 2019. If it gets to that figure, a recall election would proceed later this year, and people would decide whether to keep Sawant or oust her. If she loses her seat, the council will appoint a replacement.

In April, Washington state’s highest court dismissed an appeal by Sawant and ruled the petition process could move forward. It set campaigners a 180-day deadline to get the required signatures.

In the weeks since then, the fight on both sides has taken on a fresh intensity, with volunteers taking to the streets, to collect names, both for the recall, and in support of Sawant.

As spring arrived in the city, lighting up ward three in fruit and flower blossoms, posters for both sides – red, white and blue for the recall, and red and white for her solidarity campaign – have filled people’s windows, lawns or gardens, sometimes mingling with the roses and azaleas.

A middle-aged woman, tending to her garden on the east of the Capitol Hill district, says she supports the recall. “I would like her to represent the neighbourhood better, rather than seeking media attention,” she says.

The woman, who asks not to be named, admits the neighbourhood has changed, but says that Sawant is not interested in representing the tax-paying middle classes.

“She acts as if it is 30 years ago,” she says.

A short walk away, another woman, Lola Rogers, 56, says she is against the recall and has voted for Sawant. She says her opponents are most likely angry because of her staunch support of policies such as the $15-per hour minimum wage.

“Her goal is to spread socialist ideology,” says Rogers, who works as literary translator, specialising in Finnish.

Rogers says Sawant may not be everybody’s taste, but that she has worked hard in ward three.

“I might not want to hang out with her, or be her friend,” she says. “But I like her being on the council.”

This article was amended on 29 June 2021 to include the fact that in May this year Ms Sawant admitted having misused official resources for a ballot measure, but that at the time she said she had not wilfully disregarded any ethics rules.

Henry Bridger II says politicians must be held accountable

(Andrew Buncombe)

In addition to her push for a $15-per hour minimum wage, as a member of the city council Sawant backed a move, known as the head tax, that would have levied a charge on big employers such as Amazon, to fund services for the homeless. The measure was passed, before being repealed after opposition from the business community. (A subsequent version, known as the “JumpStart tax” was later passed.)

In 2019, Amazon controversially threw itself into Seattle city politics, spending $1.5m in support of a number of candidates for the city council it considered “pro-business”, including a challenger to Sawant. Despite its efforts, she was re-elected for a third term.

Sawant, who has been vocal in her opposition to the US’s support of Israel as well as supportive of measures such as rent control and protection against eviction, claims the region’s “corporate elite” is now backing the recall petition in an effort to get rid of her. Among the donors to the recall effort are Doug Herrington, a senior vice president at Amazon, David Stephenson, the chief financial officer at Airbnb, and Jeannie Nordstrom, a member of a department store empire, though the maximum any business or person can contribute by law is $1,000. (The Airbnb official donated just $150, records suggest, while Herrington and Nordstrom gave $1,000.)

Sawant claims her donors, by contrast, are baristas, teachers, and healthcare workers, the “whole gamut of the working class”.

“I don’t have a crystal ball,” she adds. “But I will tell you exactly what is going to happen if the recall succeeds – there will be a stunning attempt to roll back many of the victories we have won. But more than that, it will be a chilling effect on social movements.”

Airbnb had no comment about its CFO’s contribution, a Nordstrom spokesperson also declined to comment, while an Amazon spokesperson, Glenn Kuper, asked about Herrington’s donation, said: “As engaged residents and voters, our employees are welcome to support or oppose any issue or candidate they wish to in their personal capacity.”

Henry Bridger II is chair of the Recall Sawant campaign. A longtime Seattle resident, he says he voted for Sawant in 2013, though has not done so since.]

Sawant joined protesters outside a Seattle police station during last year’s racial justice demonstrations

(Getty)

He claims, however, the effort to recall Sawant is not driven by any political differences he and others may have with her, but that she broke the law. The recall campaign alleges that in addition to leading a march to the mayor’s house and hosting a protest inside city hall, in early 2020 she misused city council resources to push a ballot initiative.

(Sawant has claimed she did nothing wrong in regard to any of the allegations. However, in May she admitted misusing official resources for a ballot measure before a city ethics commission. At the time she said she “did not wilfully disregard any ethics rules”.)

Bridger insists the allegations levelled at Sawant are serious issues, and says the campaign is supported by a broad swathe of voters. He rejects assertions it is being backed by millionaires and billionaires.

“I care about any politician who breaks the law. I really do, because they impact us,” he says. “She broke the law, and we’ve already seen what happened with Trump, and how nothing sticks … It has to be done. Somebody has to step up.”

Does he equate Sawant’s alleged actions with Trump’s actions ahead of the 6 January storming of the US Capitol by his supporters?

“Absolutely. It’s the same thing,” he says. “At city hall, she endangered employees who were there by bringing in hundreds of people in the middle of a pandemic. You don’t do that, you don’t break the law, just because you feel doing it is going to get you what you want.”

Bridger, 55, who is currently unemployed, says the campaign is already more than halfway to reaching the 10,739 signatures it needs, a figure that represents 25 per cent of the total votes votes for the seat in 2019. If it gets to that figure, a recall election would proceed later this year, and people would decide whether to keep Sawant or oust her. If she loses her seat, the council will appoint a replacement.

In April, Washington state’s highest court dismissed an appeal by Sawant and ruled the petition process could move forward. It set campaigners a 180-day deadline to get the required signatures.

In the weeks since then, the fight on both sides has taken on a fresh intensity, with volunteers taking to the streets, to collect names, both for the recall, and in support of Sawant.

As spring arrived in the city, lighting up ward three in fruit and flower blossoms, posters for both sides – red, white and blue for the recall, and red and white for her solidarity campaign – have filled people’s windows, lawns or gardens, sometimes mingling with the roses and azaleas.

A middle-aged woman, tending to her garden on the east of the Capitol Hill district, says she supports the recall. “I would like her to represent the neighbourhood better, rather than seeking media attention,” she says.

The woman, who asks not to be named, admits the neighbourhood has changed, but says that Sawant is not interested in representing the tax-paying middle classes.

“She acts as if it is 30 years ago,” she says.

A short walk away, another woman, Lola Rogers, 56, says she is against the recall and has voted for Sawant. She says her opponents are most likely angry because of her staunch support of policies such as the $15-per hour minimum wage.

“Her goal is to spread socialist ideology,” says Rogers, who works as literary translator, specialising in Finnish.

Rogers says Sawant may not be everybody’s taste, but that she has worked hard in ward three.

“I might not want to hang out with her, or be her friend,” she says. “But I like her being on the council.”

This article was amended on 29 June 2021 to include the fact that in May this year Ms Sawant admitted having misused official resources for a ballot measure, but that at the time she said she had not wilfully disregarded any ethics rules.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/69537754/GettyImages_1289259419.0.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22696715/GettyImages_1228332941.jpg)