Researchers identify new meteorological phenomenon dubbed 'atmospheric lakes'

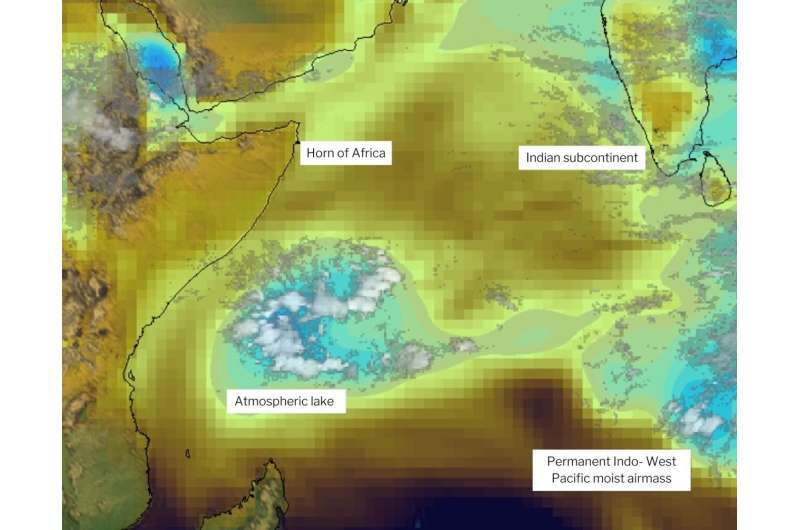

A new meteorological phenomenon has been identified drifting slowly over the western Indian Ocean. Dubbed "atmospheric lakes," these compact pools of moisture originate over the Indo-Pacific and bring water to dry lowlands along East Africa's coastline.

Brian Mapes, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Miami who recently noticed and described the unique storms, will present his findings on Thursday, 16 December at AGU's Fall Meeting 2021.

Like the better-known streams of humid, rainy air called atmospheric rivers that are famous for delivering large amounts of precipitation, atmospheric lakes start as filaments of water vapor in the Indo-Pacific. These phenomena are defined by the presence of water vapor concentrated enough to produce rain, rather than being formed and defined by a vortex, like most storms on Earth. Unlike the fast-flowing atmospheric rivers, the smaller atmospheric lakes detach from their source as they move at a sedate pace toward the coast.

Atmospheric lakes begin as water vapor streams that flow from the western side of the South Asian monsoon and pinch off to become their own measurable, isolated objects. They then float along ocean and coastal regions at the equatorial line in areas where the average wind speed is around zero.

In an initial survey to catalog such storms, Mapes used five years of satellite data to spot 17 atmospheric lakes lasting longer than six days and within 10 degrees of the equator, in all seasons. Lakes farther off the equator also occur, and sometimes those become tropical cyclones.

The atmospheric lakes last for days at a time and occur several times a year. If all the water vapor from these lakes were liquified, it would form a puddle only a few centimeters (a couple inches) deep and around 1,000 kilometers (about 620 miles) wide. This amount of water can create significant precipitation for the dry lowlands of eastern African countries where millions of people live, according to Mapes.

"It's a place that's dry on average, so when these [atmospheric lakes] happen, they're surely very consequential," Mapes said. "I look forward to learning more local knowledge about them, in this area with a venerable and fascinating nautical history where observant sailors coined the word monsoon for wind patterns, and surely noticed these occasional rainstorms, too."

Weather patterns in this region of the world have received little attention from meteorologists, limited mostly to studies of rain and water vapor on a monthly rather than day-to-day scale according to Mapes. He is working to understand why atmospheric lakes pinch off from the river-like pattern from which they form, and how and why they move westward. This might be due to some feature of the larger wind pattern, or perhaps that the atmospheric lakes are self-propelled by winds generated during rain production.

These are questions that would need to be answered before Mapes and other researchers can begin to study how climate change could affect atmospheric lake systems. He plans to study these events more closely using satellite data and will look at into the possibility that these atmospheric lakes occur elsewhere in the world.

"The winds that carry these things to ashore are so tantalizingly, delicately near zero [wind speed], that everything could affect them," Mapes said. "That's when you need to know, do they self-propel, or are they driven by some very much larger-scale wind patterns that may change with climate change."

Tropical lakes may emit more methane

More information: Paper presentation: agu.confex.com/agu/fm21/meetin … app.cgi/Paper/910339

ATMOSPHERIC LAKES CAN DUMP RAIN FOR DAYS. IMAGE CREDIT: BAKUSOVA / SHUTTERSTOCK.COM

By Rachael Funnell17 DEC 2021

If you’re someone who likes to sit out front in a rocking chair as you stroke your chin wistfully and mutter “storm’s a-brewin,” have we got good news for you. A new weather system has been detected kicking off above the Indian Ocean, a kind of storm that's a bit like a massive puddle in the sky. Meteorologists call it an “atmospheric lake”.

The novel weather system was discovered by Brian Mapes and Wei-Ming Tsai as they were investigating atmospheric water vapor looming over the Indian Ocean, presenting their findings at the AGU Fall Meeting.

An atmospheric lake is a massive aggregation of water vapor in the atmosphere, which is slow-moving and can endure for days. Using satellite data that spanned half a decade, the researchers found 17 instances of atmospheric lakes that had held true for over six days. Their emergence wasn’t season-specific and sometimes acted as a precursor to tropical cyclones, a much more dramatic weather system.

The lakes didn’t spring up out of nowhere, instead forming out of what’s known as “atmospheric rivers”. We’ve known about these weather systems for a long time and they pretty much do what it says on the tin: form fast-moving streams or “rivers” of water vapor in the atmosphere. These rivers can pinch off and slow, forming a “lake” that can hold and eventually rain an awful lot of water.

Atmospheric lakes typically form from atmospheric rivers running in from the Indo-Pacific region. These fast-running rivers can slow as they cross to Africa’s east coast, sometimes forming into atmospheric lakes that can linger for days and bring a lot of rain. Considering the climate in this part of the world, it’s likely our shiny, new (to science) weather system plays a pivotal role in the environment.

“It’s a place that’s dry on average, so when these [atmospheric lakes] happen, they’re surely very consequential,” said Mapes to New Atlas. “I look forward to learning more local knowledge about them, in this area with a venerable and fascinating nautical history where observant sailors coined the word monsoon for wind patterns, and surely noticed these occasional rainstorms, too.”

Speaking of cool weather systems, did you know that rainforests can make their own clouds? A 2021 study found that the net cooling effect of trees is likely far more significant than previously thought as until now nobody had considered how their cloud-formation impacts the climate. Clever trees.

[H/T: New Atlas]