Report: Nonreligious LGBTQ people face heightened stigma, conceal their beliefs

A new report details the extent to which nonreligious LGBTQ people experience both religious oppression and anti-LGBTQ sentiment.

(RNS) — As a Black, bisexual, nonreligious person, Rogiérs Fibby is all too familiar with the subtle navigations required of his different identities in professional and personal spaces.

“It’s sort of programmed. I’m making these adjustments and editing myself in these ways that take effort and it takes energy from my core,” said Fibby, 44, who was raised Moravian and is the director of Black Nonbelievers of DC.

A singer and producer, Fibby has found himself negotiating his identities, sometimes with people who may be homophobic or racist, but also with those who, while being pro-LGBTQ or supportive of Black Lives Matter, are uncomfortable with his lack of religion.

“There are times when I am very unapologetic and bold about asserting myself in those spaces,” said Fibby, who identifies as an atheist and agnostic. “Then there are other times where I have to make judgments and calculations that essentially are repressive. I find myself hiding and holding back.”

Rogiérs Fibby. Photo courtesy of Fibby

Sometimes he wonders, “What could you have done with that energy if you didn’t have to deal with these types of responses?”

Fibby is not alone.

RELATED: New report finds nonreligious people face stigma and discrimination

A survey of nonreligious people reveals that LGBTQ persons regularly concealed their nonreligious beliefs and are more likely than their non-LGBTQ peers to encounter stigma and discrimination in nearly every aspect of their lives — education, employment, mental health services and within their families — due to their beliefs.

The report, “Nonreligious Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer People in America,” released Tuesday (Aug. 16), details the extent to which nonreligious LGBTQ people experience both religious oppression and anti-LGBTQ sentiment as well as the level of depression among those raised in religious households.

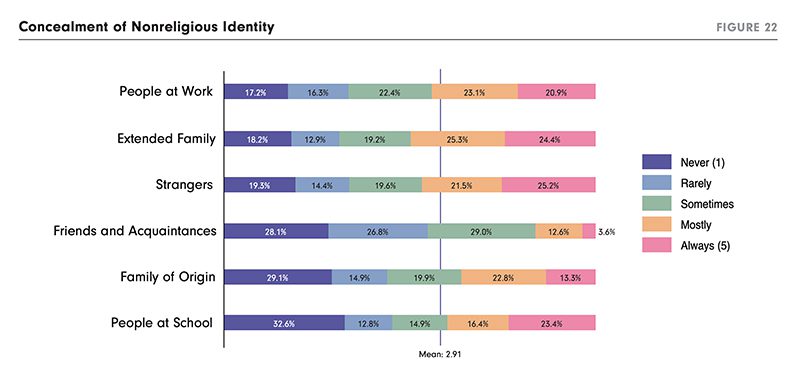

The research, based on a survey of nearly 34,000 nonreligious people in the United States, found that LGBTQ participants were about 16.1% more likely than non-LGBTQ respondents to mostly or always conceal their nonreligious identities from their families of origin.

Among those who are nonreligious and LGBTQ, a quarter said they always conceal their nonreligious beliefs (25%) with strangers, within their extended family (24%) and at school (23%). About 1 in 5 said they do so at work (21%).

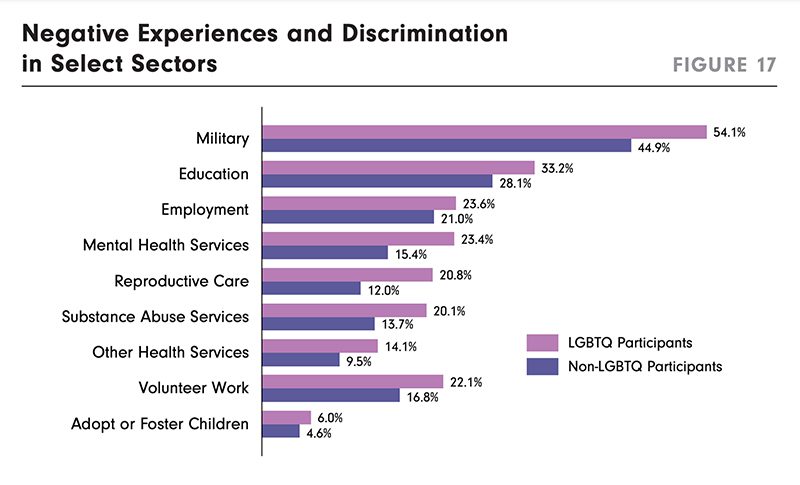

“Negative Experiences and Discrimination in Select Sectors” Graphic courtesy of American Atheists

Of the nonreligious LGBTQ people in the military, 54% reported negative experiences because of their beliefs, compared with 45% of non-LGBTQ participants. Similarly, within the education field, nonreligious LGBTQ people are more likely to report negative experiences associated with their beliefs than non-LGBTQ nonreligious (33% compared with 28%).

The report also highlighted that nearly 9 in 10 LGBTQ participants from very strict religious families had negative experiences with their family because of their nonreligious beliefs.

“Family rejection had a significant negative impact on the psychological wellbeing of LGBTQ and other participants,” according to the report.

While levels of depression were generally higher for LGBTQ participants (28%) than cisgender/heterosexual participants (14%), parental support appeared to play an important role. Of those whose parents were aware of their nonreligious identities, LGBTQ participants with unsupportive parents were almost 1.5 times as likely to be depressed as those with supportive or neutral parents (34% vs. 26%), the survey found.

“Concealment of Nonreligious Identity” Graphic courtesy of American Atheists

“This report was to really look at who we are, as a double minority, as a group that’s often targeted for being LGBTQ, but also having religious beliefs imposed upon us and feeling that stigma and discrimination for being nonreligious,” said Tom Van Denburgh, a spokesperson for American Atheists.

“Our very existence, being both LGBTQ and nonreligious, often defies and maybe even denies the possibility that we are living in a Christian conservative nation,” Van Denburgh added. “That’s problematic to a lot of religious conservatives.”

RELATED: Study: Women of no faith face discrimination — when they are seen at all

“Nonreligious Lesbian, Gay Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer People in America” Image courtesy of American Atheists

The report notes a dwindling number of LGBTQ people who identify with religion, given religious efforts meant to “stifle LGBTQ equality,” such as opposition to legal same-sex marriage, support of legislation targeting trans youth and the unwillingness of many religious groups to marry or ordain LGBTQ people.

“Some find refuge in secular communities, which, on the whole, are among the religious demographics most accepting of LGBTQ people,” according to the report.

The report referenced 2018 data showing that atheists are the religious demographic with the highest percentage of LGBTQ members. Additionally, 92% of atheists favor same-sex marriage, according to the Pew Research Center.

Nearly 23% of people who participated in the 2019 U.S. Secular Survey, which is the basis of the report, were nonreligious LGBTQ adults.

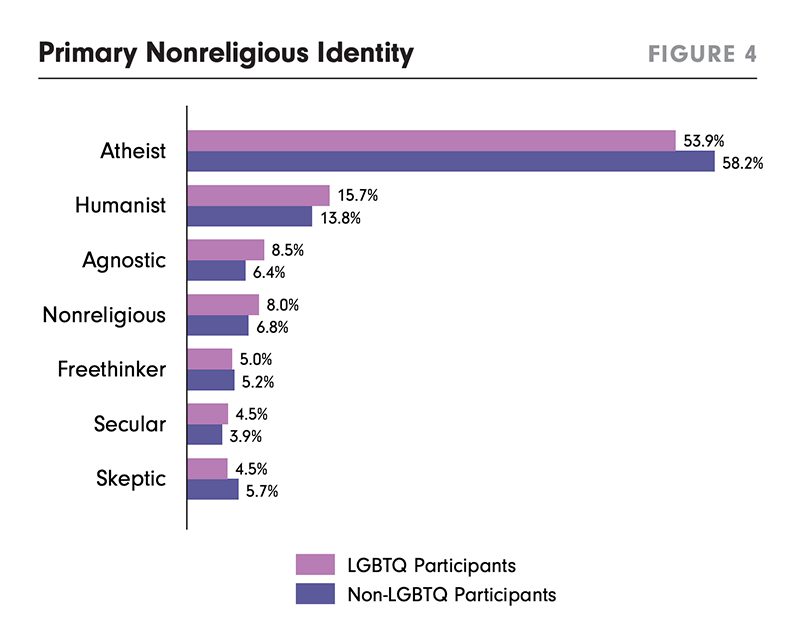

Among the surveyed nonreligious LGBTQ people, more than half (54%) identified primarily as atheists. Most were white (92%), half were female (50%), with 42% identifying as male and 16% as trans or gender nonconforming. About half said they were bisexual (49%). Nearly 60% were raised in a Protestant household.

“Primary Nonreligious Indentity” Graphic courtesy of American Atheists

For Killian Bowen, who grew up in a Pentecostal household, finding atheism as a teen was “how I escaped from the situation around me.” Bowen said he knew he was queer by around age 8.

Bowen identifies as an atheist and works as American Atheists’ assistant state director for Morehead, Kentucky.

“A part of the reason I got into atheism is because I felt such a huge amount of shame being in the religion that I was in. Atheism helps me justify my identity,” Bowen said.

With this new report, Bowen said he hopes “more people could acknowledge the fact that there is religious discrimination in every aspect of our lives, especially in the South.”