How Native Americans Guarded Their Societies Against Tyranny

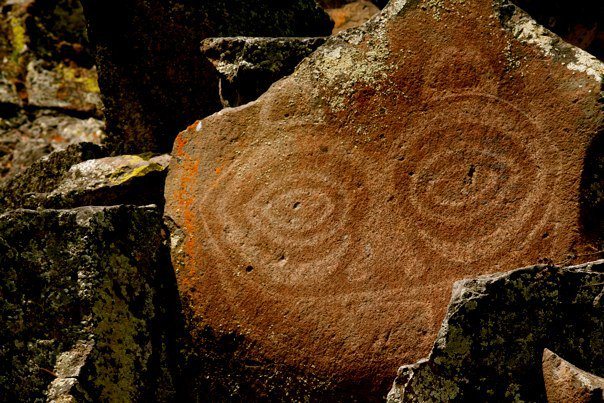

Tsagiglalal, or “She Who Watches,” pictograph in the Columbia River Gorge. Photo: Jeffrey St. Clair.

When the founders of the United States designed the Constitution, they were learning from history that democracy was likely to fail – to find someone who would fool the people into giving him complete power and then end the democracy.

They designed checks and balances to guard against the accumulation of power they had found when studying ancient Greece and Rome. But there were others in North America who had also seen the dangers of certain types of government and had designed their own checks and balances to guard against tyranny: the Native Americans.

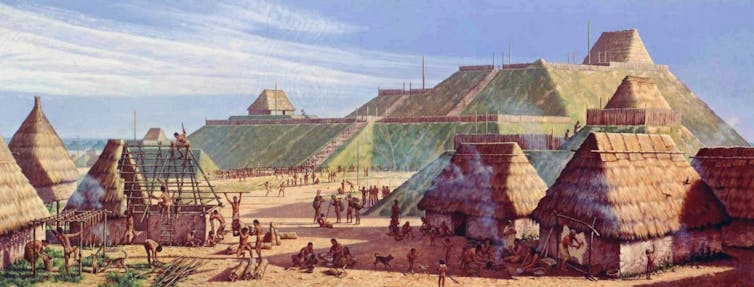

Although most Americans today don’t know it, there were large centralized civilizations across much of North America in the 10th through 12th centuries. They built massive cities and grand irrigation projects across the continent. Twelfth-century Cahokia, on the banks of the Mississippi River, had a central city about the size of London at the time. The sprawling 12th-century civilization of the Huhugam had several cities of more than 10,000 people and a total population of perhaps 50,000 in the Southwestern desert.

Michael Hampshire for the Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

The ruins of these constructions remain, more than 1,000 years later, in places as far-flung as Phoenix, St. Louis and north Georgia.

The American Colonists and founders thought Native American societies were simple and primitive – but they were not. As research has found, including my own, and as I explain in my book, “Native Nations: A Millennium in North America,” Native American communities were elaborate consensus democracies, many of which had survived for generations because of careful attention to checking and balancing power.

Powerful rulers led many of these civilizations, combining political and religious power, much as monarchs of Europe in later centuries would claim a divine right to rule.

In the 13th century, though, a global cooling trend began, which has been called the Little Ice Age. In part because of that cooling, large-scale farming became more difficult, and these large civilizations struggled to feed their people. Elites began hoarding wealth. The people wanted change.

Spreading out

The residents of North America’s great cities responded to these stresses by reversing the centralization of power and wealth. Some revolted against their leaders. Others simply left the cities and spread out into smaller towns and farms. All across the continent, they built smaller, more democratic and more egalitarian societies.

Huge numbers left Cahokia’s realm entirely. They found places that still had game to hunt and woods full of trees for firewood and building, both of which had declined near Cahokia due to its rapid growth.

The population of the central city of Cahokia fell from perhaps 20,000 people to only 3,000 by 1275. At some point the elite left as well, and by the late 15th century the cities of Cahokia’s realm were completely gone.

Encouraging engaged democracy

As they formed these new and more dispersed societies, the people who had overthrown or fled the great cities and their too powerful leaders sought to avoid mesmerizing leaders who made tempting promises in difficult times. So they designed complex political structures to discourage centralization, hierarchy and inequality and encourage shared decision-making.

These societies intentionally created balanced power structures. For example, the oral history of the Osage Nation records that it once had one great chief who was a military leader, but its council of elder spiritual leaders, known as the “Little Old Men,” decided to balance that chief’s authority with that of another hereditary chief, who would be responsible for keeping peace.

Another way some societies balanced power was through family-based clans. Clans communicated and cooperated across multiple towns. They could work together to balance the power of town-based chiefs and councils.

An ideal of leadership

Many of these societies required convening all of the people – men, women and children – for major political, military, diplomatic and land-use decisions. Hundreds or even thousands might show up, depending on how momentous the decision was.

They strove for consensus, though they didn’t always achieve it. In some societies, it was customary for the losing side to quietly leave the meeting if they couldn’t bring themselves to agree with the others.

Leaders generally governed by facilitating decision-making in council meetings and public gatherings. They gave gifts to encourage cooperation. They heard disputes between neighbors over land and resources and helped to resolve them. Power and prestige came to lie not in amassing wealth but in assuring that the wealth was shared wisely. Leaders earned support in part by being good providers.

‘Calm deliberation’

The Native American democracy that the U.S. founders were most likely to know about was the Iroquois Confederacy. They call themselves the Haudenosaunee, the “people of the longhouse,” because the nations of the confederacy have to get along like multiple families in a longhouse.

In their carefully balanced system, women ran the clans, which were responsible for local decisions about land use and town planning. Men were the representatives of their clans and nations in the Haudenosaunee council, which made decisions for the confederacy as a whole. Each council member, called a royaner, was chosen by a clan mother.

The Haudenosaunee Great Law holds a royaner to a high standard: “The thickness of their skin shall be seven spans – which is to say that they shall be proof against anger, offensive actions and criticism. Their hearts shall be full of peace and good will.” In council, “all their words and actions shall be marked by calm deliberation.”

The law said the ideal royaner should always “look and listen for the welfare of the whole people and have always in view not only the present but also the coming generations, even those whose faces are yet beneath the surface of the ground – the unborn of the future Nation.”

Of course, people do not always live up to their values, but the laws and traditions of Native nations encouraged peaceful discussion and broad-mindedness. Many Europeans were struck by the difference. The French explorer La Salle in 1678 noted with admiration of the Haudenosaunee that “in important meetings, they discuss without raising their voices and without getting angry.”

Politicians, government officials and everyday Americans might find inspiration in the models of democracy created by Native Americans centuries ago. There was an additional ingredient to the political and social balance: Leaders looked ahead and sought to protect the well-being of every person, even those not yet born. The people, in exchange, had a responsibility to not enmesh their royaners in less serious matters, which the Haudenosaunee Great Law called “trivial affairs.”![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.