U.S. coronavirus deaths top 100,000 as country reopens

The novel coronavirus has killed more than 100,000 people in the United States, according to a Reuters tally on Wednesday, even as the slowdown in deaths encouraged businesses to reopen and Americans to emerge from more than two months of lockdowns.

It’s possible that I shall make an ass of myself. But in that case one can always get out of it with a little dialectic. I have, of course, so worded my proposition as to be right either way (K.Marx, Letter to F.Engels on the Indian Mutiny)

Thursday, May 28, 2020

Diary from a Genocide in the Making

By Margaret M. Seiler

Field Notes

Out of the Darkness, Port of Entry at Gateway International Bridge, 3/14/20. Photo: Tom Cartwright.

I spent a week on the US/Mexico border in February with a grassroots group called Witness at the Border. It was my second trip this year, since we launched a daily vigil in Xeriscape Park in Brownsville, Texas, in mid-January. “Witnesses” from over 30 states and abroad have come to bear witness to the horror wrought by the current administration’s cruel immigration policies. A steady drumbeat of incomprehensibly racist policies keeps escalating. First, the travel (or Muslim) ban, then family separation, then children in cages, then “Remain in Mexico” (absurdly called the Migrant Protection Protocols, or MPP), and now an alphabet soup of stealth policies—PACR, HARP, ACA—that fast track the deportation of asylum seekers. As each new policy unfurls, quicker than the ACLU and other human rights groups can challenge them in court, another one pops up. Cruelty is the point.

“Witnessing is the subversive act of seeing what our government doesn’t want us to see: the cruel consequences of our policies, hidden behind fences and walls,” says immigration activist and Brooklynite Joshua Rubin, founder of Witness at the Border. “We cannot stop what we cannot see.”

So I went to see with my own eyes the atrocity of asylum seekers fleeing violence—men, women, and children—forced by the MPP policy to live in a squalid encampment for the homeless in Matamoros, Mexico. Many others are scraping by all over the city, a city ruled by drug cartels and gangs, as dangerous as most in Syria, a city the US State Department advises Americans not to visit. I came to bear witness to the sham that is the “tent court” system. I came to see people whose only crime is running from danger, asking for refuge only to be loaded by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officers onto airplanes, in shackles, deported to danger.

January 11: Justice at the Border

Deporting asylum seekers back to danger, Brownsville International Airport. Photo: Allan Mestel

Deporting asylum seekers back to danger, Brownsville International Airport. Photo: Allan Mestel

On my first day in Brownsville, I visited with other witnesses at Xeriscape Park, a small green space across the street from the Gateway International Bridge to Matamoros. What is witnessing? It’s holding up signs reading “Let Them Cross,” “Seeking Asylum is Legal,” “Love Has No Borders,” “Amor, No Odio. (Love, Not Hate.)” It’s waving to passersby who honk their car horns and wave back. (Brownsville is about 90% Latino.) It’s nodding hello and greeting the many folks walking by on their way into Brownsville after crossing over the bridge from Matamoros: “Buenos dias.” Witnessing is observing, noticing, recording, Tweeting, posting on Facebook, visiting the tent courts or the airport—again, to observe, witness, record, and testify.

On my visit to a Brownsville “courtroom,” held in large white tents, I sat in the back with a few other observers on folding chairs. ICE officers led 15 migrants in, about two thirds men, one third women, and one 11-year-old girl. They filled the first two rows of the courtroom and waited patiently for the judge to show up on a large video screen in order to begin the proceedings. Each migrant has at least one, usually three calendar hearings, spaced weeks apart. They are asked if they’ve filled out their application for asylum completely and in English, if they’ve found an attorney, then they’re given another date to return. The judge was in a courtroom nearby in Harlingen with a prosecuting attorney from the Justice Department and a Spanish language translator. Visitors are only allowed into the calendar hearings—and they only opened to us after complaints in the press. The final stage is a merits hearing; in it, arguments of the case for and against removal are presented in order to determine whether asylum is granted or not—no visitors are allowed. Of the 15 migrants in court that day only two had lawyers; one had a lawyer that was present and the other one had a lawyer calling in from Miami.

When you face your judge on a screen while they are in some faraway courtroom, the distance created between you and them is palpable. Can they see a tear or hear the tremor in a voice? Can they see a father rubbing his young daugher’s back as she quietly kicks her feet? Is this something deliberate to keep the proceedings impersonal and easier on the judge?

Back in the park, a lawyer waiting to go to court visited with us. “It’s Kafka on the border,” she said. “Asylum court is like traffic court, only it’s life or death.”

February 12: Migrant Persecution Protocols

We sat in front of a huge banner made by Miami-based artist Alessandra Mondolfi, that in bold red and black letters reads: MPP KILLS. Out of the corner of my eye, I saw a young Latino man crossing the street from the bridge towards us, grinning ear to ear.

“MPP!” he shouted out, smiling and pointing at the banner. “Si! No bueno, MPP… Muchas gracias!!” He said again, smiling from ear to ear with two thumbs up. Then we noticed his telltale gallon plastic bag filled with paperwork. Next thing I knew, Cat had leapt up and wrapped the young man in a bear hug. Other friends were lining up to greet him.

“Soy libre! Gane asilo” (I’m free! I won asylum), he said. Bienvenidos!(Welcome!) we said.

We pieced together a bit of his story with our limited Spanish. All his family in Honduras had been murdered. His brother was waiting for him in the US while he’d been stuck in the Matamoros encampment for six months. Cat handed him a snack she had in her cooler, and we asked him what he needed. He asked for a phone to call his brother in Florida. We soon found out there were no flights left out of Brownsville that day. A kind volunteer with Team Brownsville, a local nonprofit that assists asylum seekers, escorted him to a shelter where he could shower, get a hot meal, and spend the night. We were overjoyed, but he was one of the lucky few; 0.1%. That’s what his chances of being awarded asylum were—0.1%. This young man had beaten the odds.

Over a year has passed since MPP was instituted in another Texas border city, El Paso, where all new policies are launched by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). Now seven sites along the border, Nogales, Arizona; San Diego, California; and, all in Texas, Calexico, El Paso, Laredo, Brownsville, and Eagle Pass, enforce this draconian policy. When asylum seekers arrive at ports of entry, they present themselves to US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officers to claim a “credible fear” of remaining in their home country. Instead of allowing them in and quickly moving them from detention facilities to sponsors or family members in the US while they wait for their court hearings, our officers say, “Go back. Wait in Mexico. Here’s a number and a date. See you in a couple months!”

As a result, encampments of homeless migrants have sprung up along the border. While there are shelters in Mexico, they are usually located deep inside these dangerous cities. Matamoros has been issued its harshest no-travel warning; a level 4 warning, like the ones in war torn Syria. Migrants in the shelters live far from the bridges connected to the US, where armed guards provide some semblance of safety. What's more, how can it be expected of them to even be able to get to the bridge early on their court date when they must line up at four a.m., four hours in advance in order to make it to their 8 a.m. appointment, due to long wait lines? How would they even access American lawyers?, which they need. The lawyers know what could happen to them in Mexico, and even the most intrepid ones will not dare to travel deep into cities like Jaurez and Matamoros. Because of this, asylum seekers prefer to remain close to the bridge, nestled together, offering each other some sense of community and safety. That is until nightfall, when they are prey for gang members who know the migrants have contacts in the US. Kidnapping them has become a cottage industry. Sexual violence and rape are common occurences even among young children.

The Matamoros encampment, the largest of the makeshift refugee camps along the border, grew from a few dozen people last summer to over 2,500 recently. Walking through, I saw families washing their clothes in the river, rows upon rows of donated two-person tents in which whole families sleep, set on the dirt, some with donated mattresses and others in sleeping bags. I saw men and boys hauling cut wood to use with ingeniously devised stoves made from sticks and mud; some made with tubes of discarded washing machines. Tree limbs and chain link fences were dotted with drying laundry—squares of pink and blue and red hanging beside and above the mounds of tents.

What struck me most were the kids. They were everywhere. Girls with beautifully braided hair, toddlers caked in mud, boys kicking soccer balls on the dusty paths. There’s a charging station for phones where you can find a dozen people talking, and rows of porta-potties. Running water has finally been set up by volunteer groups; a small health clinic is run by Global Resource Management. A huge tent went up in late January for meals served by World Central Kitchen, assisted by the heroic Team Brownsville. There is no sense of danger. People are friendly. I’ve heard the camp is very orderly. Tasks are assigned, groups often arranged by nationality set themselves chores, such as filling up donated trash bags. Most are Hondurans, then Mexicans, Guatemalans, Salvadorans, Nicaraguans, and even some Venezuelans. Outside the camp, those with money, often the Cubans and Venezuelans, rent apartments and rooms. Or so I hear.

I spent a week on the US/Mexico border in February with a grassroots group called Witness at the Border. It was my second trip this year, since we launched a daily vigil in Xeriscape Park in Brownsville, Texas, in mid-January. “Witnesses” from over 30 states and abroad have come to bear witness to the horror wrought by the current administration’s cruel immigration policies. A steady drumbeat of incomprehensibly racist policies keeps escalating. First, the travel (or Muslim) ban, then family separation, then children in cages, then “Remain in Mexico” (absurdly called the Migrant Protection Protocols, or MPP), and now an alphabet soup of stealth policies—PACR, HARP, ACA—that fast track the deportation of asylum seekers. As each new policy unfurls, quicker than the ACLU and other human rights groups can challenge them in court, another one pops up. Cruelty is the point.

“Witnessing is the subversive act of seeing what our government doesn’t want us to see: the cruel consequences of our policies, hidden behind fences and walls,” says immigration activist and Brooklynite Joshua Rubin, founder of Witness at the Border. “We cannot stop what we cannot see.”

So I went to see with my own eyes the atrocity of asylum seekers fleeing violence—men, women, and children—forced by the MPP policy to live in a squalid encampment for the homeless in Matamoros, Mexico. Many others are scraping by all over the city, a city ruled by drug cartels and gangs, as dangerous as most in Syria, a city the US State Department advises Americans not to visit. I came to bear witness to the sham that is the “tent court” system. I came to see people whose only crime is running from danger, asking for refuge only to be loaded by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officers onto airplanes, in shackles, deported to danger.

January 11: Justice at the Border

Deporting asylum seekers back to danger, Brownsville International Airport. Photo: Allan Mestel

Deporting asylum seekers back to danger, Brownsville International Airport. Photo: Allan MestelOn my first day in Brownsville, I visited with other witnesses at Xeriscape Park, a small green space across the street from the Gateway International Bridge to Matamoros. What is witnessing? It’s holding up signs reading “Let Them Cross,” “Seeking Asylum is Legal,” “Love Has No Borders,” “Amor, No Odio. (Love, Not Hate.)” It’s waving to passersby who honk their car horns and wave back. (Brownsville is about 90% Latino.) It’s nodding hello and greeting the many folks walking by on their way into Brownsville after crossing over the bridge from Matamoros: “Buenos dias.” Witnessing is observing, noticing, recording, Tweeting, posting on Facebook, visiting the tent courts or the airport—again, to observe, witness, record, and testify.

On my visit to a Brownsville “courtroom,” held in large white tents, I sat in the back with a few other observers on folding chairs. ICE officers led 15 migrants in, about two thirds men, one third women, and one 11-year-old girl. They filled the first two rows of the courtroom and waited patiently for the judge to show up on a large video screen in order to begin the proceedings. Each migrant has at least one, usually three calendar hearings, spaced weeks apart. They are asked if they’ve filled out their application for asylum completely and in English, if they’ve found an attorney, then they’re given another date to return. The judge was in a courtroom nearby in Harlingen with a prosecuting attorney from the Justice Department and a Spanish language translator. Visitors are only allowed into the calendar hearings—and they only opened to us after complaints in the press. The final stage is a merits hearing; in it, arguments of the case for and against removal are presented in order to determine whether asylum is granted or not—no visitors are allowed. Of the 15 migrants in court that day only two had lawyers; one had a lawyer that was present and the other one had a lawyer calling in from Miami.

When you face your judge on a screen while they are in some faraway courtroom, the distance created between you and them is palpable. Can they see a tear or hear the tremor in a voice? Can they see a father rubbing his young daugher’s back as she quietly kicks her feet? Is this something deliberate to keep the proceedings impersonal and easier on the judge?

Back in the park, a lawyer waiting to go to court visited with us. “It’s Kafka on the border,” she said. “Asylum court is like traffic court, only it’s life or death.”

February 12: Migrant Persecution Protocols

We sat in front of a huge banner made by Miami-based artist Alessandra Mondolfi, that in bold red and black letters reads: MPP KILLS. Out of the corner of my eye, I saw a young Latino man crossing the street from the bridge towards us, grinning ear to ear.

“MPP!” he shouted out, smiling and pointing at the banner. “Si! No bueno, MPP… Muchas gracias!!” He said again, smiling from ear to ear with two thumbs up. Then we noticed his telltale gallon plastic bag filled with paperwork. Next thing I knew, Cat had leapt up and wrapped the young man in a bear hug. Other friends were lining up to greet him.

“Soy libre! Gane asilo” (I’m free! I won asylum), he said. Bienvenidos!(Welcome!) we said.

We pieced together a bit of his story with our limited Spanish. All his family in Honduras had been murdered. His brother was waiting for him in the US while he’d been stuck in the Matamoros encampment for six months. Cat handed him a snack she had in her cooler, and we asked him what he needed. He asked for a phone to call his brother in Florida. We soon found out there were no flights left out of Brownsville that day. A kind volunteer with Team Brownsville, a local nonprofit that assists asylum seekers, escorted him to a shelter where he could shower, get a hot meal, and spend the night. We were overjoyed, but he was one of the lucky few; 0.1%. That’s what his chances of being awarded asylum were—0.1%. This young man had beaten the odds.

Over a year has passed since MPP was instituted in another Texas border city, El Paso, where all new policies are launched by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). Now seven sites along the border, Nogales, Arizona; San Diego, California; and, all in Texas, Calexico, El Paso, Laredo, Brownsville, and Eagle Pass, enforce this draconian policy. When asylum seekers arrive at ports of entry, they present themselves to US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officers to claim a “credible fear” of remaining in their home country. Instead of allowing them in and quickly moving them from detention facilities to sponsors or family members in the US while they wait for their court hearings, our officers say, “Go back. Wait in Mexico. Here’s a number and a date. See you in a couple months!”

As a result, encampments of homeless migrants have sprung up along the border. While there are shelters in Mexico, they are usually located deep inside these dangerous cities. Matamoros has been issued its harshest no-travel warning; a level 4 warning, like the ones in war torn Syria. Migrants in the shelters live far from the bridges connected to the US, where armed guards provide some semblance of safety. What's more, how can it be expected of them to even be able to get to the bridge early on their court date when they must line up at four a.m., four hours in advance in order to make it to their 8 a.m. appointment, due to long wait lines? How would they even access American lawyers?, which they need. The lawyers know what could happen to them in Mexico, and even the most intrepid ones will not dare to travel deep into cities like Jaurez and Matamoros. Because of this, asylum seekers prefer to remain close to the bridge, nestled together, offering each other some sense of community and safety. That is until nightfall, when they are prey for gang members who know the migrants have contacts in the US. Kidnapping them has become a cottage industry. Sexual violence and rape are common occurences even among young children.

The Matamoros encampment, the largest of the makeshift refugee camps along the border, grew from a few dozen people last summer to over 2,500 recently. Walking through, I saw families washing their clothes in the river, rows upon rows of donated two-person tents in which whole families sleep, set on the dirt, some with donated mattresses and others in sleeping bags. I saw men and boys hauling cut wood to use with ingeniously devised stoves made from sticks and mud; some made with tubes of discarded washing machines. Tree limbs and chain link fences were dotted with drying laundry—squares of pink and blue and red hanging beside and above the mounds of tents.

What struck me most were the kids. They were everywhere. Girls with beautifully braided hair, toddlers caked in mud, boys kicking soccer balls on the dusty paths. There’s a charging station for phones where you can find a dozen people talking, and rows of porta-potties. Running water has finally been set up by volunteer groups; a small health clinic is run by Global Resource Management. A huge tent went up in late January for meals served by World Central Kitchen, assisted by the heroic Team Brownsville. There is no sense of danger. People are friendly. I’ve heard the camp is very orderly. Tasks are assigned, groups often arranged by nationality set themselves chores, such as filling up donated trash bags. Most are Hondurans, then Mexicans, Guatemalans, Salvadorans, Nicaraguans, and even some Venezuelans. Outside the camp, those with money, often the Cubans and Venezuelans, rent apartments and rooms. Or so I hear.

March to Shine a Light on the Border. February 15, 2020, Brownsville. Photo: Allan Mestel.

In March, the 9th Circuit in California ruled that MPP was illegal. For about 10 hours people rejoiced. Migrants flooded (not rushed!) the bridges, wondering what this all meant. The government requested a stay, which they got. Within a week, the Supreme Court had swooped in: MPP is here to stay, for now.

February 14: #DeportedToDanger

On Valentine’s Day, I awoke at 5 a.m. I dragged myself out of bed, leaving the scratchy, motel sheets behind. I hurried to meet my friends at the Brownsville International Airport by 6 a.m. About 30 “witnesses” were there to show some love to the Central American asylum seekers, only to see them shackled like career criminals, in 5-point restraints, being moved onto Swift Air planes by beefy Border Patrol officers in shiny yellow vests. The seekers were moms, dads, teenage girls with swinging black hair, even toddlers. What was most disturbing was the banality of it all. This was just another morning at the border: our government deporting the unwanted and ignored back to danger.

We gathered at the airport just before dawn. There was a chill in the air. It was dark. As we walked to the lot where four busloads full of human cargo sat, the sun came up. I saw palm trees silhouetted against a rosy sky dotted with gray clouds. Up beside the busses, the glass windows were tinted dark but, standing close, we held up red cardboard hearts that we’d made for Valentine’s Day. We saw people sitting inside and they could see us. We sang out, “No estan solos! (You are not alone!)” “Te queremos! (We love you!)”

“They were lifting up their shackles and showing us, so we knew what situation they were in,” said Camilo Perez-Bustillo, a human rights attorney and researcher. “This is clearly a flagrant human rights violation. It’s a violation of international law because we’re having people sent back who are facing danger in their home countries, who are entitled to international protection, refuge and asylum, and the US is denying it.”

ICE officers huddled together, waiting to see if we’d leave. After about 30 minutes, they told us to move off private property. No one wanted to get arrested so we moved to stand next to a large chain link fence where we watched the busses pull up next to white airplanes that seat about 150 people. ICE parked some trucks so our view was blocked but we still managed to see men, women, and children climb out of the busses. They lined up one by one, adults in shackles. An officer patted each one down, checked their hair and the inside of their mouths. Then the restrained asylum seekers awkwardly made their way up the stairs into the plane, heads bowed, the girls’ long hair flapping in the wind, flying back to danger.

Since November, over 800 Honduran and Salvadoran asylum seekers have been deported to Guatemala under the Trump administration’s Guatemalan Asylum Cooperative Agreement (ACA), according to journalist Jeff Abbott on Twitter. “The majority are women and children.” he wrote in early March, “only 14 have applied for asylum.” Trump signed a so-called “safe third country agreement” with Guatemala last July. The deal states that asylum seekers traveling through a third country to the US must first apply for asylum in the countries they pass through. If they arrive at the US-Mexico border without doing so, they are quickly deported to Guatemala—not their home country—by DHS. They are then given 72 hours to apply for asylum there, or leave the country.

Yael Schacher of Refugees International visited Casa del Migrante, a shelter in Guatemala City, in early February. She interviewed about 20 deportees from the US.

Many of the people were misled, they were led to believe that they would be transferred here and they could actually apply for asylum in the US here, which is not the case. Most of them don’t want to seek asylum here in Guatemala, which isn’t safe for them. It doesn’t have the capacity to process their applications. There’s no place for them to stay, no family here, but they also don’t want to go back to their home country because most of them have fled violence and have protection needs and can’t go back there. Some of them will, out of desperation. Others are trying to find any way possible to seek safe haven elsewhere.

The Honduran “safe third country agreement” is expected to start being implemented soon, if it hasn’t been already. First we sent them to Guatemala, and now Honduras and El Salvador, under programs called PACR (Prompt Asylum Claim Review) and HARP (Humanitarian Asylum Review Process), which is for Mexicans. Witness at the Border has been going to the airport frequently, documenting with photographs and video these deportations.

[PACR and HARP] are the deployment of the most direct strategy yet for preventing people from getting relief in our country….We have reports that these unwilling passengers have not been advised of any rights they might have, and some arrived confused about where they are, hungry, and severely stressed….For our government, this has the advantage of being even further out of sight than the hellish border cities of Mexico…. Our government celebrates the lower numbers of the desperate here in the US, which they attribute to the reduced likelihood of people finding hope for themselves and their families in the country that has disowned the lamp lifted in New York Harbor.

wrote Josh Rubin on February 26, 2020.

January 12/February 13: Just Kids

Matamoros encampment of asylum seekers. Photo: Allan Mestel.

Matamoros encampment of asylum seekers. Photo: Allan Mestel.

It’s Sunday morning in Matamoros: Escuelita de la Banqueta (School on the Sidewalk). I arrived at the Brownsville bus station at 8:15 to greet a slew of volunteers taking supplies out of Dr. Melba Lucio-Salazar’s car and loading them in plastic carts—donated books, crayons, drawing paper, pens, markers, pencils. We hauled them across the International Bridge—four quarters needed to cross, no passport on the way over, only back—and to the back of the encampment where we set up blue tarps on the dirt under large white, open air tents. I piled the supplies I’d brought: a picture book in Spanish, colored pencils, and paper. A local group teaches yoga to the kids—teens in one area, 8–12 year olds in the middle, and the littlest kids together. (We’ve heard there are 700 kids in the camp.) I squeeze onto a yoga mat somewhere in the middle and stretch out in a downward dog. Little boys tumble and roll over each other, laughing and wrestling.

When yoga ends, about an hour of instruction begins, interspersed with the ever-popular snack time. I have about 20 minutes with each group—8–10 year olds, 5–7 year olds, under 5s—moving from tarp to tarp. My first group swarms over me: “Sientese, por favor) It’s chaotic, but fun. As a former teacher, I know when to instantly adapt a lesson to the group in front of me—no one speaks English so I drop my plan to introduce new English words. I read the picture book and ask questions in my mediocre Spanish: “Que es su color favorito?” (What is your favorite color?) “Que es su animal favorito?” (What is your favorite animal?)

“Dibujalo“ (Draw it!)

A boy about four years old, in a hoodie and flip flops, excitedly bops up and down next to me, grabbing the book I’m trying to read. I pat my lap and he climbs into it, my arm drawing him close. Better. Much later, as we’re all leaving the tent, he sees me holding my phone, and gestures to me for a selfie. I snap a few and he grins as I show them to him. In February, I volunteer at the Sidewalk School for Children Asylum Seekers, started by a Texas native, Felicia Rangel-Samponaro, which is now run every weekday from 4:30–6:30. This month a new school is slated to begin, a school in a bus run by the Yes We Can World Foundation. Meanwhile, bright kids of all ages—from toddlers to teens—are not getting the kind of quality education they could get if they lived in a stable community. If they could just go to their family and sponsors in the US while their parents proceed through the court system, which is their legal right.

February 15: The Wall

On Saturday, we marched and protested through the streets of Brownsville, waving our signs and banners against this injustice. Those who have worked on the frontlines with immigrants for years—Catholic nuns, RAICES, the Texas Civil Rights Project, ACLU-TX—have welcomed Witness at the Border. Our mission is political. While the vital humanitarian work of feeding, clothing, and providing medicine to needy asylum seekers is carried out daily by stalwart locals like Sergio Cordova, Michael Benavides, and Andrea Rudnick of Team Brownsville, our job is to MAKE SOME NOISE. We need outrage! Family separation is not over! Kids are still being tortured! Human rights abuses in our name, with our tax dollars!

So we stood next to the Wall, an enormous steel barrier up against the Rio Grande, and listened to Texans on the frontline of immigrant justice talk about their work. A leader of the Carrizo/Comecrudo Tribe of Texas talked about colonialism and indigenous people’s fight to preserve their land and their culture in the Rio Grande Valley, about the environmental degradation of the Wall, and the inhumanity of it all. We talked about the need for more witnesses, more national outrage.

Through the bars of the wall, across the blue-green river under a brilliant blue sky, not far away, we saw a family resting on the banks. We waved at each other across the invisible border. So close by.

February 16: The Kids, Part II

On Sunday, we held a memorial for the seven children who have died in Border Patrol custody (or one soon after) during the past year and a half:

Felipe Gomez Alonzo, 8, Guatemala

Darlyn Cristabel Cordova-Valle, 10, El Salvador

Juan de Leon Gutierrez, 16, Guatemala

Mariee Juarez, 19 months, Guatemala

Jakelin Caal Maquin, 7, Guatemala

Carlos Gregorio Hernandez Vasquez, 16, Guatemala

Wilmer Josue Ramirez Vasquez, 2, Guatemala

Marina Vasquez, a nurse who lives in Austin, arranged an altar with pictures of the children, candles, a beautiful cloth and a quilt with the image of the Virgin of Guadalupe. She spoke prayerfully about the children. Camilo, the human rights attorney, spoke about the historical context of how we got here: conflicts in Central America, US greed, intervention and duplicity. Then he read the poem, “Floaters”, by Martín Espada (excerpted here).

And the dead have a name: floaters, say the men of the Border Patrol,

keeping watch all night by the river, hearts pumping coffee as they say

the word floaters, soft as a bubble, hard as a shoe as it nudges the body, to see

if it breathes, to see if it moans, to see if it sits up and speaks….

And the dead still have names, names that sing in praise of the saints,

names that flower in blossoms of white, a cortege of names dressed

all in black, trailing the coffins to the cemetery….Enter their names in the

book of names.

Say Óscar Alberto Martínez Ramírez; say Angie Valeria Martínez Ávalos….”

Afterwards, we traipsed over to a stage to listen to speakers and hear music. Dr. Amy Cohen is a child and family psychiatrist who currently advises attorneys working with children in detention centers and families who have been separated by immigration policies. She has interviewed children held in government custody and, for much of her 30-year career, has treated traumatized children.

This is a holocaust of danger being visited upon the young. Children whose only crime has been to seek safety from the deadly conditions of their home countries. I don’t want to have to see—as I did a week ago—the child in my office who weeps and trembles even TWO YEARS LATER as she recalls the cruelty of the officers who separated her from her mother and then threatened to send her back to her country all by herself if she cried. Officers who locked her into a crowded, freezing cage bathed in perpetual light and then came into that cage, went up to her on the concrete floor, and kicked her because, exhausted from her quiet weeping, she’d fallen asleep.

I don’t want the call about the 1–1/2 year old child desperate for treatment for pneumonia, which she contracted as a complication of not one but two barely treated infections she contracted in the squalid conditions of American detention….Some medical professional signed the order to have this sick child discharged from the hospital without medication so she could be put on a plane to a third country where she, her mother and her sister knew no one and had no resources whatsoever. If a child dies in Guatemala because of American policies, will we ever know?

I don’t want to have to come down to the border to help parents to face the excruciating decision of whether or not to separate from their children to keep them alive. Whether to send them across the bridge by themselves, these small children they have held in their arms to protect through the dangerous journey to what they thought was safety. Watching them disappear as they cross that bridge on their own, praying that they will be safe. Because our government is now exposing them to the VERY SAME DANGERS of violence that they faced in the countries they fled. No parent should have to make that decision.

You thought family separation ended? Make no mistake. This administration is nimble. And MPP is yet another child separation program.

February 18: What Fathers Do

Amy asked me to accompany her when she visited with families at the Resource Center of Matamoros, where Project Corazon, a project of Lawyers for Good Government, tries to stem the tide with only two full time lawyers. A young doctor from Philadelphia joined Amy and me to translate. X, a young father from Honduras, arrived with his ten-year-old daughter, V. Amy, who speaks like a kind preschool teacher or an angel, gently spoke to the girl, giving her crayons and drawing paper. Then turned her attention to X:

“So let’s talk about your decision to get your daughter across the border by herself.”

X explained how he had to carry two IDs in Honduras—he showed them to us. Gang members would stop him in the street: one gang was shown one ID, the other gang the other. Finally, he was attacked too many times, his life and his family’s lives threatened too intensely. Still, the court questioned why he’d waited six months to leave home with his daughter—are you really in danger? Seriously? Why would you wait so long?

“What would you do? You have to figure it out! Where do I go? How do I leave my whole life behind? It takes a while,” he says in Spanish. He finally convinced his wife to take their three-year-old son and hide at her parents while he and V made the trek north.

“We’ve been here five months, in the camp. I had my third hearing and they denied me asylum, because I waited so long to come. They didn’t believe me when I said if I go home, I’ll be killed. I guess I’ll have to go home eventually but I want V to get across and go to my cousin. She’s in Houston,” he says. “And someday, I’ll get there too.”

V is drawing a beautiful drawing of a house with flowers in the windows. I smile at her and offer her more colored pencils. She is hearing every word.

A discussion goes back and forth about the cousin. Does X have any family in New York or California (the best states to seek asylum)? No, one in Maryland, but a single man, not the best sponsor for a ten-year-old daughter. They discuss how best to get V across the bridge so she can spend the minimum amount of time in detention and/or foster care, and then on to the Houston cousin. X shows us a picture of himself six months ago, when he was 30 pounds heavier. He pulls up his shirt to show us his psoriasis. “El estres.” (The stress.)

We spent over an hour with X and V. That evening I spoke to my friend, Gale, who also helped with translation. She had spent the afternoon with Amy, who interviewed six other families. “That father and daughter were heartbreaking, no?” I asked Gale. “How was the afternoon?” “Horrifying. A mother is fleeing domestic violence. Her husband has connections in the Guatemalan government so he was able to locate her. She got a call that he’s coming to the camp to kill her. Their eight-year-old son is in foster care in Pennsylvania. Amy is desperately trying to get both mom and the boy to safe houses.”

These are the bad hombres.

Since this article was written, asylum has been virtually banned and court hearings postponed.The Witness at the Border vigil in Brownsville has been suspended for now due to COVID-19. Follow our website to learn more. Support Amy Cohen’s work at Every.Last.One. Support health care in Matamoros: Global Response Management. Support Amy Cohen’s work at Every.Last.One. Support health care in Matamoros: Global Response Management.

ContributorMargaret M. Seiler

Margaret M. Seiler is an educator and activist living in Brooklyn, New York. Besides her work with Witness at the Border, she volunteers with two NYC-based groups promoting humane immigration policies and supporting asylum seekers: Don’t Separate Families and Team TLC NYC.

In March, the 9th Circuit in California ruled that MPP was illegal. For about 10 hours people rejoiced. Migrants flooded (not rushed!) the bridges, wondering what this all meant. The government requested a stay, which they got. Within a week, the Supreme Court had swooped in: MPP is here to stay, for now.

February 14: #DeportedToDanger

On Valentine’s Day, I awoke at 5 a.m. I dragged myself out of bed, leaving the scratchy, motel sheets behind. I hurried to meet my friends at the Brownsville International Airport by 6 a.m. About 30 “witnesses” were there to show some love to the Central American asylum seekers, only to see them shackled like career criminals, in 5-point restraints, being moved onto Swift Air planes by beefy Border Patrol officers in shiny yellow vests. The seekers were moms, dads, teenage girls with swinging black hair, even toddlers. What was most disturbing was the banality of it all. This was just another morning at the border: our government deporting the unwanted and ignored back to danger.

We gathered at the airport just before dawn. There was a chill in the air. It was dark. As we walked to the lot where four busloads full of human cargo sat, the sun came up. I saw palm trees silhouetted against a rosy sky dotted with gray clouds. Up beside the busses, the glass windows were tinted dark but, standing close, we held up red cardboard hearts that we’d made for Valentine’s Day. We saw people sitting inside and they could see us. We sang out, “No estan solos! (You are not alone!)” “Te queremos! (We love you!)”

“They were lifting up their shackles and showing us, so we knew what situation they were in,” said Camilo Perez-Bustillo, a human rights attorney and researcher. “This is clearly a flagrant human rights violation. It’s a violation of international law because we’re having people sent back who are facing danger in their home countries, who are entitled to international protection, refuge and asylum, and the US is denying it.”

ICE officers huddled together, waiting to see if we’d leave. After about 30 minutes, they told us to move off private property. No one wanted to get arrested so we moved to stand next to a large chain link fence where we watched the busses pull up next to white airplanes that seat about 150 people. ICE parked some trucks so our view was blocked but we still managed to see men, women, and children climb out of the busses. They lined up one by one, adults in shackles. An officer patted each one down, checked their hair and the inside of their mouths. Then the restrained asylum seekers awkwardly made their way up the stairs into the plane, heads bowed, the girls’ long hair flapping in the wind, flying back to danger.

Since November, over 800 Honduran and Salvadoran asylum seekers have been deported to Guatemala under the Trump administration’s Guatemalan Asylum Cooperative Agreement (ACA), according to journalist Jeff Abbott on Twitter. “The majority are women and children.” he wrote in early March, “only 14 have applied for asylum.” Trump signed a so-called “safe third country agreement” with Guatemala last July. The deal states that asylum seekers traveling through a third country to the US must first apply for asylum in the countries they pass through. If they arrive at the US-Mexico border without doing so, they are quickly deported to Guatemala—not their home country—by DHS. They are then given 72 hours to apply for asylum there, or leave the country.

Yael Schacher of Refugees International visited Casa del Migrante, a shelter in Guatemala City, in early February. She interviewed about 20 deportees from the US.

Many of the people were misled, they were led to believe that they would be transferred here and they could actually apply for asylum in the US here, which is not the case. Most of them don’t want to seek asylum here in Guatemala, which isn’t safe for them. It doesn’t have the capacity to process their applications. There’s no place for them to stay, no family here, but they also don’t want to go back to their home country because most of them have fled violence and have protection needs and can’t go back there. Some of them will, out of desperation. Others are trying to find any way possible to seek safe haven elsewhere.

The Honduran “safe third country agreement” is expected to start being implemented soon, if it hasn’t been already. First we sent them to Guatemala, and now Honduras and El Salvador, under programs called PACR (Prompt Asylum Claim Review) and HARP (Humanitarian Asylum Review Process), which is for Mexicans. Witness at the Border has been going to the airport frequently, documenting with photographs and video these deportations.

[PACR and HARP] are the deployment of the most direct strategy yet for preventing people from getting relief in our country….We have reports that these unwilling passengers have not been advised of any rights they might have, and some arrived confused about where they are, hungry, and severely stressed….For our government, this has the advantage of being even further out of sight than the hellish border cities of Mexico…. Our government celebrates the lower numbers of the desperate here in the US, which they attribute to the reduced likelihood of people finding hope for themselves and their families in the country that has disowned the lamp lifted in New York Harbor.

wrote Josh Rubin on February 26, 2020.

January 12/February 13: Just Kids

Matamoros encampment of asylum seekers. Photo: Allan Mestel.

Matamoros encampment of asylum seekers. Photo: Allan Mestel.It’s Sunday morning in Matamoros: Escuelita de la Banqueta (School on the Sidewalk). I arrived at the Brownsville bus station at 8:15 to greet a slew of volunteers taking supplies out of Dr. Melba Lucio-Salazar’s car and loading them in plastic carts—donated books, crayons, drawing paper, pens, markers, pencils. We hauled them across the International Bridge—four quarters needed to cross, no passport on the way over, only back—and to the back of the encampment where we set up blue tarps on the dirt under large white, open air tents. I piled the supplies I’d brought: a picture book in Spanish, colored pencils, and paper. A local group teaches yoga to the kids—teens in one area, 8–12 year olds in the middle, and the littlest kids together. (We’ve heard there are 700 kids in the camp.) I squeeze onto a yoga mat somewhere in the middle and stretch out in a downward dog. Little boys tumble and roll over each other, laughing and wrestling.

When yoga ends, about an hour of instruction begins, interspersed with the ever-popular snack time. I have about 20 minutes with each group—8–10 year olds, 5–7 year olds, under 5s—moving from tarp to tarp. My first group swarms over me: “Sientese, por favor) It’s chaotic, but fun. As a former teacher, I know when to instantly adapt a lesson to the group in front of me—no one speaks English so I drop my plan to introduce new English words. I read the picture book and ask questions in my mediocre Spanish: “Que es su color favorito?” (What is your favorite color?) “Que es su animal favorito?” (What is your favorite animal?)

“Dibujalo“ (Draw it!)

A boy about four years old, in a hoodie and flip flops, excitedly bops up and down next to me, grabbing the book I’m trying to read. I pat my lap and he climbs into it, my arm drawing him close. Better. Much later, as we’re all leaving the tent, he sees me holding my phone, and gestures to me for a selfie. I snap a few and he grins as I show them to him. In February, I volunteer at the Sidewalk School for Children Asylum Seekers, started by a Texas native, Felicia Rangel-Samponaro, which is now run every weekday from 4:30–6:30. This month a new school is slated to begin, a school in a bus run by the Yes We Can World Foundation. Meanwhile, bright kids of all ages—from toddlers to teens—are not getting the kind of quality education they could get if they lived in a stable community. If they could just go to their family and sponsors in the US while their parents proceed through the court system, which is their legal right.

February 15: The Wall

On Saturday, we marched and protested through the streets of Brownsville, waving our signs and banners against this injustice. Those who have worked on the frontlines with immigrants for years—Catholic nuns, RAICES, the Texas Civil Rights Project, ACLU-TX—have welcomed Witness at the Border. Our mission is political. While the vital humanitarian work of feeding, clothing, and providing medicine to needy asylum seekers is carried out daily by stalwart locals like Sergio Cordova, Michael Benavides, and Andrea Rudnick of Team Brownsville, our job is to MAKE SOME NOISE. We need outrage! Family separation is not over! Kids are still being tortured! Human rights abuses in our name, with our tax dollars!

So we stood next to the Wall, an enormous steel barrier up against the Rio Grande, and listened to Texans on the frontline of immigrant justice talk about their work. A leader of the Carrizo/Comecrudo Tribe of Texas talked about colonialism and indigenous people’s fight to preserve their land and their culture in the Rio Grande Valley, about the environmental degradation of the Wall, and the inhumanity of it all. We talked about the need for more witnesses, more national outrage.

Through the bars of the wall, across the blue-green river under a brilliant blue sky, not far away, we saw a family resting on the banks. We waved at each other across the invisible border. So close by.

February 16: The Kids, Part II

On Sunday, we held a memorial for the seven children who have died in Border Patrol custody (or one soon after) during the past year and a half:

Felipe Gomez Alonzo, 8, Guatemala

Darlyn Cristabel Cordova-Valle, 10, El Salvador

Juan de Leon Gutierrez, 16, Guatemala

Mariee Juarez, 19 months, Guatemala

Jakelin Caal Maquin, 7, Guatemala

Carlos Gregorio Hernandez Vasquez, 16, Guatemala

Wilmer Josue Ramirez Vasquez, 2, Guatemala

Marina Vasquez, a nurse who lives in Austin, arranged an altar with pictures of the children, candles, a beautiful cloth and a quilt with the image of the Virgin of Guadalupe. She spoke prayerfully about the children. Camilo, the human rights attorney, spoke about the historical context of how we got here: conflicts in Central America, US greed, intervention and duplicity. Then he read the poem, “Floaters”, by Martín Espada (excerpted here).

And the dead have a name: floaters, say the men of the Border Patrol,

keeping watch all night by the river, hearts pumping coffee as they say

the word floaters, soft as a bubble, hard as a shoe as it nudges the body, to see

if it breathes, to see if it moans, to see if it sits up and speaks….

And the dead still have names, names that sing in praise of the saints,

names that flower in blossoms of white, a cortege of names dressed

all in black, trailing the coffins to the cemetery….Enter their names in the

book of names.

Say Óscar Alberto Martínez Ramírez; say Angie Valeria Martínez Ávalos….”

Afterwards, we traipsed over to a stage to listen to speakers and hear music. Dr. Amy Cohen is a child and family psychiatrist who currently advises attorneys working with children in detention centers and families who have been separated by immigration policies. She has interviewed children held in government custody and, for much of her 30-year career, has treated traumatized children.

This is a holocaust of danger being visited upon the young. Children whose only crime has been to seek safety from the deadly conditions of their home countries. I don’t want to have to see—as I did a week ago—the child in my office who weeps and trembles even TWO YEARS LATER as she recalls the cruelty of the officers who separated her from her mother and then threatened to send her back to her country all by herself if she cried. Officers who locked her into a crowded, freezing cage bathed in perpetual light and then came into that cage, went up to her on the concrete floor, and kicked her because, exhausted from her quiet weeping, she’d fallen asleep.

I don’t want the call about the 1–1/2 year old child desperate for treatment for pneumonia, which she contracted as a complication of not one but two barely treated infections she contracted in the squalid conditions of American detention….Some medical professional signed the order to have this sick child discharged from the hospital without medication so she could be put on a plane to a third country where she, her mother and her sister knew no one and had no resources whatsoever. If a child dies in Guatemala because of American policies, will we ever know?

I don’t want to have to come down to the border to help parents to face the excruciating decision of whether or not to separate from their children to keep them alive. Whether to send them across the bridge by themselves, these small children they have held in their arms to protect through the dangerous journey to what they thought was safety. Watching them disappear as they cross that bridge on their own, praying that they will be safe. Because our government is now exposing them to the VERY SAME DANGERS of violence that they faced in the countries they fled. No parent should have to make that decision.

You thought family separation ended? Make no mistake. This administration is nimble. And MPP is yet another child separation program.

February 18: What Fathers Do

Amy asked me to accompany her when she visited with families at the Resource Center of Matamoros, where Project Corazon, a project of Lawyers for Good Government, tries to stem the tide with only two full time lawyers. A young doctor from Philadelphia joined Amy and me to translate. X, a young father from Honduras, arrived with his ten-year-old daughter, V. Amy, who speaks like a kind preschool teacher or an angel, gently spoke to the girl, giving her crayons and drawing paper. Then turned her attention to X:

“So let’s talk about your decision to get your daughter across the border by herself.”

X explained how he had to carry two IDs in Honduras—he showed them to us. Gang members would stop him in the street: one gang was shown one ID, the other gang the other. Finally, he was attacked too many times, his life and his family’s lives threatened too intensely. Still, the court questioned why he’d waited six months to leave home with his daughter—are you really in danger? Seriously? Why would you wait so long?

“What would you do? You have to figure it out! Where do I go? How do I leave my whole life behind? It takes a while,” he says in Spanish. He finally convinced his wife to take their three-year-old son and hide at her parents while he and V made the trek north.

“We’ve been here five months, in the camp. I had my third hearing and they denied me asylum, because I waited so long to come. They didn’t believe me when I said if I go home, I’ll be killed. I guess I’ll have to go home eventually but I want V to get across and go to my cousin. She’s in Houston,” he says. “And someday, I’ll get there too.”

V is drawing a beautiful drawing of a house with flowers in the windows. I smile at her and offer her more colored pencils. She is hearing every word.

A discussion goes back and forth about the cousin. Does X have any family in New York or California (the best states to seek asylum)? No, one in Maryland, but a single man, not the best sponsor for a ten-year-old daughter. They discuss how best to get V across the bridge so she can spend the minimum amount of time in detention and/or foster care, and then on to the Houston cousin. X shows us a picture of himself six months ago, when he was 30 pounds heavier. He pulls up his shirt to show us his psoriasis. “El estres.” (The stress.)

We spent over an hour with X and V. That evening I spoke to my friend, Gale, who also helped with translation. She had spent the afternoon with Amy, who interviewed six other families. “That father and daughter were heartbreaking, no?” I asked Gale. “How was the afternoon?” “Horrifying. A mother is fleeing domestic violence. Her husband has connections in the Guatemalan government so he was able to locate her. She got a call that he’s coming to the camp to kill her. Their eight-year-old son is in foster care in Pennsylvania. Amy is desperately trying to get both mom and the boy to safe houses.”

These are the bad hombres.

Since this article was written, asylum has been virtually banned and court hearings postponed.The Witness at the Border vigil in Brownsville has been suspended for now due to COVID-19. Follow our website to learn more. Support Amy Cohen’s work at Every.Last.One. Support health care in Matamoros: Global Response Management. Support Amy Cohen’s work at Every.Last.One. Support health care in Matamoros: Global Response Management.

ContributorMargaret M. Seiler

Margaret M. Seiler is an educator and activist living in Brooklyn, New York. Besides her work with Witness at the Border, she volunteers with two NYC-based groups promoting humane immigration policies and supporting asylum seekers: Don’t Separate Families and Team TLC NYC.

ArtSeen

Against, Again: Art Under Attack in Brazil

By Sumeja Tulic

Jaime Lauriano, America, 2020. Drawing made with black pemba (chalk used in rituals of Umbanda), dermatographic pencil, charcoal and golden self-adhesive high tack tape on cotton. 150 x 160 cm. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Alex Korolkovas/Courtesy of AnnexB.

ON VIEW

ON VIEW

Anya and Andrew Shiva Gallery

New York

What happens when nostalgia and the future collide? A very complicated present, befitting a group show. Against, Again: Art Under Attack in Brazil presents the work of more than 30 artists whose practices respond to the seemingly cyclical waves of authoritarianism brought back into full swing in Brazil with the election of the far-right president Jair Bolsonaro. Since his inauguration in January of 2019, Bolsonaro, a retired military officer and admirer and ally of President Trump, has begun a steady attack against the Brazilian democracy and its institution, threatening and censuring political opposition, activists, intellectuals, and artists. In addition to being a vocal opponent of same-sex marriage, environmental regulations, abortion, affirmative action, immigration, drug liberalization, land reform, and secularism, Bolsonaro is a staunch defender of the Brazilian military dictatorship (1964–1985) and its torture practices.

The show begins with America: democracia racial, melting pot and pureza de razas (2019) by São Paulo based Jaime Lauriano, whose work often deals with institutional violence and historical traumas. Here, he resurrects the aesthetics of colonial cartography and “the discovery of the new world” on a white textile, drawing the Americas with the black chalk used in the rituals of a syncretic Afro-Brazilian religion. America distinguishes itself from colonial cartography by concretizing, in language, with honesty and irony, the ideals and deceptions of the settler-colonial expansion and its genocidal practices. In Lauriano’s map, instead of the Atlantic Ocean the viewer reads in Portuguese "Racial Democracy" while "Race Purity" takes the place of the Pacific Ocean. “The Melting Pot” is spelled out in quaint typography over the lands of North America.

While Lauriano’s work examines the production and representations of history, the decades-long practice of Maria Thereza Alves has been concerned with the detrimental effects of the Portuguese imperialism on the indigenous peoples of Brazil as well as the impact of the Spanish conquest on the Americas. The show features two iterations of Alves’s meeting with her mentor, indigenous leader Tupã-Y Guaraní (Marçal de Souza). The first, from 1980, is a black-and-white photograph of Guaraní standing at the edge of his tribe’s land in the interior state of Mato Grosso do Sul, pointing at the mountain that once marked its border. The other documentation Alves presents is an audio recording of a conversation she had with Guaraní, also in 1980, which is played as the soundtrack of a single-frame video made of the photograph, which has been colorized, of Guaraní pointing at the mountain. During their discussion, Guaraní explains that a union of indigenous peoples has been formed and encourages Alves to join the fight for indigenous rights. Three years after their meeting, in 1983, Guaraní was brutally murdered by a Euro-Brazilian landowner wanting his tribal lands.

New York

What happens when nostalgia and the future collide? A very complicated present, befitting a group show. Against, Again: Art Under Attack in Brazil presents the work of more than 30 artists whose practices respond to the seemingly cyclical waves of authoritarianism brought back into full swing in Brazil with the election of the far-right president Jair Bolsonaro. Since his inauguration in January of 2019, Bolsonaro, a retired military officer and admirer and ally of President Trump, has begun a steady attack against the Brazilian democracy and its institution, threatening and censuring political opposition, activists, intellectuals, and artists. In addition to being a vocal opponent of same-sex marriage, environmental regulations, abortion, affirmative action, immigration, drug liberalization, land reform, and secularism, Bolsonaro is a staunch defender of the Brazilian military dictatorship (1964–1985) and its torture practices.

The show begins with America: democracia racial, melting pot and pureza de razas (2019) by São Paulo based Jaime Lauriano, whose work often deals with institutional violence and historical traumas. Here, he resurrects the aesthetics of colonial cartography and “the discovery of the new world” on a white textile, drawing the Americas with the black chalk used in the rituals of a syncretic Afro-Brazilian religion. America distinguishes itself from colonial cartography by concretizing, in language, with honesty and irony, the ideals and deceptions of the settler-colonial expansion and its genocidal practices. In Lauriano’s map, instead of the Atlantic Ocean the viewer reads in Portuguese "Racial Democracy" while "Race Purity" takes the place of the Pacific Ocean. “The Melting Pot” is spelled out in quaint typography over the lands of North America.

While Lauriano’s work examines the production and representations of history, the decades-long practice of Maria Thereza Alves has been concerned with the detrimental effects of the Portuguese imperialism on the indigenous peoples of Brazil as well as the impact of the Spanish conquest on the Americas. The show features two iterations of Alves’s meeting with her mentor, indigenous leader Tupã-Y Guaraní (Marçal de Souza). The first, from 1980, is a black-and-white photograph of Guaraní standing at the edge of his tribe’s land in the interior state of Mato Grosso do Sul, pointing at the mountain that once marked its border. The other documentation Alves presents is an audio recording of a conversation she had with Guaraní, also in 1980, which is played as the soundtrack of a single-frame video made of the photograph, which has been colorized, of Guaraní pointing at the mountain. During their discussion, Guaraní explains that a union of indigenous peoples has been formed and encourages Alves to join the fight for indigenous rights. Three years after their meeting, in 1983, Guaraní was brutally murdered by a Euro-Brazilian landowner wanting his tribal lands.

Maria Thereza Alves, Marçal Tupã Y (Tupã-Y Guaraní, Marçal de Souza), 1980. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Alex Korolkovas/Courtesy of AnnexB.

Despite a recent drop in murders in Brazil, violent crimes continue to plague the country—a problem compounded by the use of lethal force by Brazilian police. An Apology to Elephants (2019), a video by Brooklyn-based Anna Parisi (b. 1984), is dedicated to five children, ranging from 8 to 12 years old, who were killed in Rio de Janeiro’s favelas during police raids. The video begins with footage of a baby elephant, “…so cute, young and plump… docile eyes…so dark,” the narrator says, walking down a road, before the video shifts its tone. An older elephant then is punished by a trainer, a white, middle-aged woman. The training sequence dissolves into footage of police breaking into a favela, gathering boys and men, hitting and degrading their black and brown bodies, which the police body cameras render gray and blue.

Despite a recent drop in murders in Brazil, violent crimes continue to plague the country—a problem compounded by the use of lethal force by Brazilian police. An Apology to Elephants (2019), a video by Brooklyn-based Anna Parisi (b. 1984), is dedicated to five children, ranging from 8 to 12 years old, who were killed in Rio de Janeiro’s favelas during police raids. The video begins with footage of a baby elephant, “…so cute, young and plump… docile eyes…so dark,” the narrator says, walking down a road, before the video shifts its tone. An older elephant then is punished by a trainer, a white, middle-aged woman. The training sequence dissolves into footage of police breaking into a favela, gathering boys and men, hitting and degrading their black and brown bodies, which the police body cameras render gray and blue.

Berna Reale, Camuflagem #01 (Camouflage #01), 2018. Inkjet print with mineral pigment on paper, 100 x 150 cm. Courtesy the artist and Galeria Nara Roesler, São Paulo and New York. Photo: Alex Korolkovas/Courtesy of AnnexB.

Also on view is Camuflagem #01 (2018), a photograph by the performance artist Berna Reale (b.1965), who is known for using her body in constructing reflections on social conflicts and disparities. For Camuflagem #01, Reale wears a military uniform while pushing a wagon carrying bundles that are shaped like human corpses and made from sheets used to cover victims of violence that Reale, who is also a forensic investigator, sourced from her colleagues working in police departments. In Camuflagem #01, Reale's back is to the camera—the bodily position of a perfect target.

The show also includes Inserções em circuitos ideológicos: Projeto cédula ("Insertions into Ideological Circuits: Banknote Project"), the work of the acclaimed conceptual artist and sculptor Cildo Meireles (b.1948). For this installation, made in 1970, Meireles stamped official banknotes with subversive messages and then returned them to regular circulation, including one asking "Quem Matou Herzog?" or "Who Killed Herzog?" The question refers to the death by torture of the journalist Vlado Herzog, a vocal opponent of the military dictatorship, by the police. Herzog’s murder was officially reported as suicide. The Banknote Project exemplifies Meireles’s practice of producing unexpected opportunities for viewer engagement as he did again in response to the 2018 murder of Marielle Franco, a Rio de Janeiro councilwoman, feminist, human rights activist, and outspoken critic of police brutality and extrajudicial killings. In 2019, two former police officers were arrested and charged with her murder. Before their arrest, both suspects had pictures taken with Bolsonaro. Recently, several Brazilian media outlets reported that the police were investigating possible ties of Bolsonaro’s second son, Carlos, to the murder.

Originally the title of a book by the Viennese-born writer Stefan Zweig, “Brazil is the land of the future,” is a repeated refrain amongst Brazilians envisioning what is to come as a society marked by plurality, diversity, and economic prosperity. In the past few years, the latter part of the phrase, "and always will be," has been replaced by "but that future never arrives." Between the idealism and resolve of the first and irony of the second accompanying phrase is a positive-bias. This positive-bias, common to all people and not just Brazilians, refuses to acknowledge the future as an adverse condition immune to the promises of historical and technological progress. Some of that future is the present, quarantined life sustaining the world.

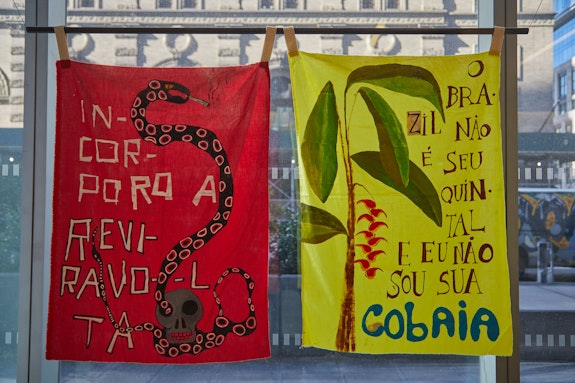

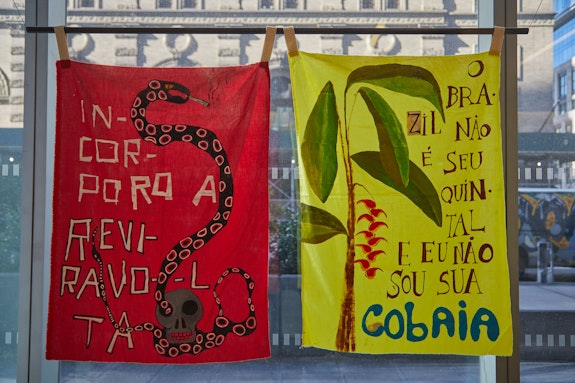

#CóleraAlegria, Selection of protest flags and slideshow with images of protests, 2016–ongoing. Dimensions variable. Courtesy the artists. Photo: Alex Korolkovas/Courtesy of AnnexB.

#CóleraAlegria, Selection of protest flags and slideshow with images of protests, 2016–ongoing. Dimensions variable. Courtesy the artists. Photo: Alex Korolkovas/Courtesy of AnnexB.

On the way out of the gallery are works by the collaborative action project #CóleraAlegria, which creates banners, posters, and flags for political demonstrations and online campaigns. On the day the gallery reopened after closing for one day because of the COVID-19 outbreak, between two gallery shifts, the front desk was empty. Befittingly to the moment and scene, #CóleraAlegria's poster hung above the desk and the empty chair: "Democracy, what time will she return?"

ContributorSumeja Tulic

is a contributor to the Rail.

Also on view is Camuflagem #01 (2018), a photograph by the performance artist Berna Reale (b.1965), who is known for using her body in constructing reflections on social conflicts and disparities. For Camuflagem #01, Reale wears a military uniform while pushing a wagon carrying bundles that are shaped like human corpses and made from sheets used to cover victims of violence that Reale, who is also a forensic investigator, sourced from her colleagues working in police departments. In Camuflagem #01, Reale's back is to the camera—the bodily position of a perfect target.

The show also includes Inserções em circuitos ideológicos: Projeto cédula ("Insertions into Ideological Circuits: Banknote Project"), the work of the acclaimed conceptual artist and sculptor Cildo Meireles (b.1948). For this installation, made in 1970, Meireles stamped official banknotes with subversive messages and then returned them to regular circulation, including one asking "Quem Matou Herzog?" or "Who Killed Herzog?" The question refers to the death by torture of the journalist Vlado Herzog, a vocal opponent of the military dictatorship, by the police. Herzog’s murder was officially reported as suicide. The Banknote Project exemplifies Meireles’s practice of producing unexpected opportunities for viewer engagement as he did again in response to the 2018 murder of Marielle Franco, a Rio de Janeiro councilwoman, feminist, human rights activist, and outspoken critic of police brutality and extrajudicial killings. In 2019, two former police officers were arrested and charged with her murder. Before their arrest, both suspects had pictures taken with Bolsonaro. Recently, several Brazilian media outlets reported that the police were investigating possible ties of Bolsonaro’s second son, Carlos, to the murder.

Originally the title of a book by the Viennese-born writer Stefan Zweig, “Brazil is the land of the future,” is a repeated refrain amongst Brazilians envisioning what is to come as a society marked by plurality, diversity, and economic prosperity. In the past few years, the latter part of the phrase, "and always will be," has been replaced by "but that future never arrives." Between the idealism and resolve of the first and irony of the second accompanying phrase is a positive-bias. This positive-bias, common to all people and not just Brazilians, refuses to acknowledge the future as an adverse condition immune to the promises of historical and technological progress. Some of that future is the present, quarantined life sustaining the world.

#CóleraAlegria, Selection of protest flags and slideshow with images of protests, 2016–ongoing. Dimensions variable. Courtesy the artists. Photo: Alex Korolkovas/Courtesy of AnnexB.

#CóleraAlegria, Selection of protest flags and slideshow with images of protests, 2016–ongoing. Dimensions variable. Courtesy the artists. Photo: Alex Korolkovas/Courtesy of AnnexB.On the way out of the gallery are works by the collaborative action project #CóleraAlegria, which creates banners, posters, and flags for political demonstrations and online campaigns. On the day the gallery reopened after closing for one day because of the COVID-19 outbreak, between two gallery shifts, the front desk was empty. Befittingly to the moment and scene, #CóleraAlegria's poster hung above the desk and the empty chair: "Democracy, what time will she return?"

ContributorSumeja Tulic

is a contributor to the Rail.

Field Notes

New Pandemic, Old Story

One of the most remarkable aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic is the way it has made visible and concrete the links between the social, economic, and political systems we have created for ourselves and our health. These links have been manifested both in the effects of the pandemic itself as well as in the ways we have responded (or failed to respond) to it. A second no less remarkable aspect is the sheer magnitude and unprecedented nature of the global response, a response that has perhaps made it possible to experience glimmers of ways in which we could live and be organized differently. Whether the experience will lead to real change, or whether after deaths begin to drop (and the disease settles into endemic transmission among the most vulnerable) we will all return to business as usual remains to be seen.

On a very practical level, one striking aspect of the pandemic response has been how unprepared we appear to have been, despite decades of pandemic preparedness exercises. A striking example has been that a country like the United States, one of the wealthiest countries in the world and the one that spends the largest percentage of GDP on health care, failed miserably to respond to basic needs generated by the growing spread of the virus. Nothing illustrates this more clearly than the lack of access to the tests needed to identify cases and the scarcity of protective equipment needed to protect health care workers from becoming infected themselves. Given the critical importance of case identification and contact tracing as the core public health approach to controlling epidemics in early stages, it is likely that the scarcity of testing was a major determinant of the inability to stop the spread earlier resulting in extensive community transmission and the consequent need for draconian stay-at-home measures. The inability to ensure even the most basic protective gear for health care workers (so-called PPE or personal protective equipment) has placed many at risk. The ongoing saga regarding the availability and distribution of ventilators, which even had US states bidding against each other1 is yet another example. It could be argued that the surge in cases was faster than anticipated, yet even well into the pandemic it has been extremely challenging to provide these basic resources when and where they are needed. Where is “the invisible hand of the market” when we really need it?

Of course, the lack of testing and PPE are manifestations of a much broader problem: the lack of a coordinated and cohesive public health response for the country as a whole. As a result, jurisdictions all over the US have responded as best they can, often piecemeal and with minimum (if any) coordination across adjacent geographic areas. To make things worse, the limited access to testing has meant not only that case identification for purposes of isolation and contact becomes impossible but also that basic statistics regarding the epidemiology of the disease are just not available. We have limited data on the rate at which new cases are occurring or on the proportion of the population that has already been infected. Some suggest that in some settings cases may actually be as much as 10 times higher2 than those reported. Lack of testing may also be skewing key measures like the case fatality rate (the proportion of cases that die) as well as information on the proportion of all infections that are asymptomatic, and on how soon after acquiring the infection people can transmit the disease. Data like these are critical to modelling efforts that attempt to predict the number of cases, the number of hospitalized cases, and the number of deaths that we can expect within specific time periods. Lack of information on these very basic aspects of the epidemiology of the virus are behind the highly variable estimates of the impact of the pandemic generated by various modelling groups. Only recently has the Centers for Disease Control (the premier public health agency of the United States and many would argue across the world) announced the launching of a series of population studies aimed at obtaining vital information needed to guide our response. Although it has consistently issued clear guidance via its website, the agency has been amazingly absent in guiding and coordinating national policy which has been left to politicians with variable scientific input. In this vacuum various individuals, ad-hoc groups of scientists, and think tanks have put forward multiple point plans on how we should respond, often disseminated through journal articles, social media or the press. [(As I write this, several US governors have announced that they plan to form coalitions to do the sensible thing and begin to coordinate responses across states.)]

On a more positive note, it has been striking to observe how the health threat created by the virus motivated a halt to business as usual in ways that no one would have imagined, with the explicit goal of protecting health. As it became apparent that case identification and contact tracing was not going to work to stop transmission, place after place (sometimes whole countries, sometimes cities, sometimes states) adopted “stay at home orders” or even more restrictive curfews. In a matter of weeks schools, universities, and “non-essential” businesses grounded to a halt. Life was completely transformed. Children stayed home, universities shifted to remote teaching, large portions of the workforce were instructed to work from home, all social activities and non-essential travel ceased. All this, as has been repeatedly emphasized in the press, to “flatten the curve” in order to reduce the burden of cases on the health care system and hopefully to reduce the number of deaths. Regardless of whether one believes this was justified or not, at least on the face of it, it was an unprecedented prioritization of health over the economy. Only an infectious disease pandemic, something everyone could relate to because of the fear of “contagion” (and the images of refrigerated trailers holding bodies in New York City), could accomplish this. None of the other silent killers, the 4.2 million deaths3 attributable to air pollution every year, the 1.35 million road traffic fatalities4 worldwide each year, the over 250,000 annual deaths caused by firearms5 (nearly 700 a day), the increasing mortality and morbidity linked to climate change (heat, drought, and floods) have been enough to make us question, let alone interfere with, our economy. For comparison purposes, on the day I am writing this (April 12 2020) the World Health Organization reports a total of 112,652 deaths from COVID-19, although questions remain about the accuracy with which deaths are being attributed or not to the virus.

The fact that this social distancing was implemented so quickly and so pervasively is mind boggling. Surreal images of empty city streets abound. It is hard to deny that social distancing will have an impact on reducing disease transmission although the magnitude of this impact and how it compares to other options (such as intensive case identification and contact tracing coupled with some more limited social distancing measures) is hard to determine. Numerous modelling efforts have reported often widely disparate estimates of cases and deaths expected, and speculation about whether the social distancing measures have or have not worked abounds. We probably will not know for sure for a long time (if at all), when retrospective studies have been performed. But given the threat of large numbers of deaths and an overwhelmed health care system (which was certainly real in some regions like northern Italy and even New York City), there was consensus despite significant uncertainty (and even skepticism among some scientists) that no other option was possible. [(Certainly the need for drastic measures appears to be justified by recent data suggesting that deaths in New York City during the last month were more than twice6 what would have been expected.)]

Aside from its impact on the pandemic itself, the social distancing policies are a grand natural experiment that could affect health in many different ways. One of the obvious consequences is the impact of stay-at-home orders on the slowdown of economic activity with its consequences for unemployment. This was starkly illustrated by the 17 million unemployment claims filed in the US since the start of the pandemics until April 9. Many studies have documented short-term effects of unemployment on the deterioration of physical and mental health with implications not only for those who lose their jobs but for their families.