The Machine Stops: Will Gompertz reviews EM Forster's work ★★★★★

My wife was listening to a radio programme the other day and heard a man talking about artificial intelligence. He mentioned a science fiction novella by EM Forster called The Machine Stops, published in 1909. He said it was remarkably prescient. The missus hadn't heard of it, and nor had I. Frankly, we didn't have Forster down as a sci-fi guy, more Merchant Ivory films starring Helena Bonham Carter and elegant Edwardian dresses.

We ordered a copy (you can read it for free online).

OMG! as Forster would not have said.

The Machine Stops is not simply prescient; it is a jaw-droppingly, gob-smackingly, breath-takingly accurate literary description of lockdown life in 2020.

If it had been written today it would be excellent, that it was written over a century ago is astonishing.

WLC PUBLISHING

WLC PUBLISHING

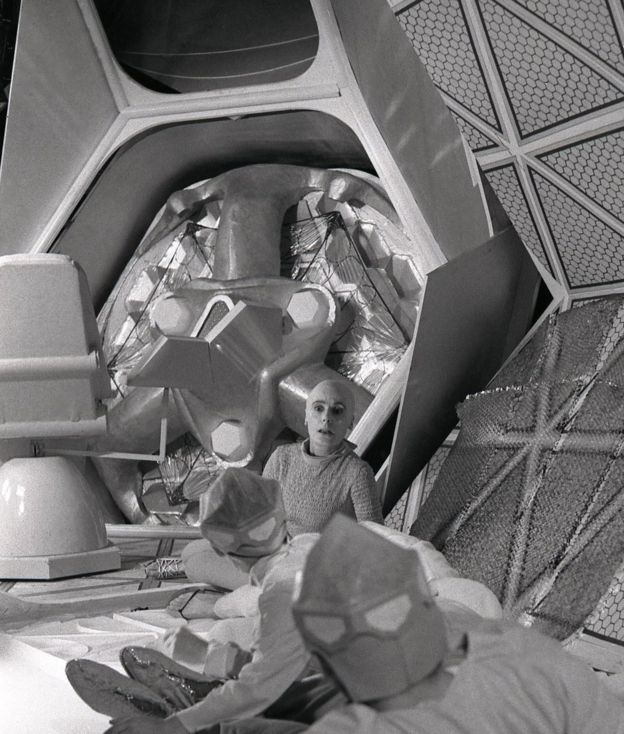

The short story is set in what must have seemed a futuristic world to Forster but won't to you. People live alone in identikit homes (globalisation) where they choose to isolate (his word), send messages by pneumatic post (a proto email or WhatsApp), and chat online via a video interface uncannily similar to Zoom or Skype.

"The clumsy system of public gatherings had long since been abandoned", along with touching strangers ("the custom had become obsolete"), now considered verboten in this new civilisation in which humans live in underground cells with an Alexa-like computer catering to their every whim.

If it already sounds spookily close for comfort, you won't be reassured to know that members of this detached society know thousands of people via machine-controlled social networks that encourage users to receive and impart second-hand ideas.

"In certain directions human intercourse had advanced enormously" writes the visionary author drily, before adding later:

"But humanity, in its desire for comfort, had over-reached itself. It had exploited the riches of nature too far. Quietly and complacently, it was sinking into decadence, and progress had come to mean progress of the machine."

SHUTTERSTOCK

SHUTTERSTOCK

It's not lost on me that you are reading this on the internet on a man-made device over which we just about still believe we have mastery. Not for long according to Forster's story, nor, I suspect, some of the boffins behind AI today.

We are in Frankenstein's monster territory, another literary warning we probably shouldn't ignore.

Forster has no similar scary physical manifestation of science going wrong in The Machine Stops (the title says it all), but that brings it even closer to home. The tale's two protagonists, Vashti and her son Kuno, are normal people, just like you or me. She lives in the southern hemisphere, he lives in the north.

Kuno wants his mother to visit. She isn't keen.

"But I can see you!" she exclaimed. "What more do you want?"

"I want to see you not through the Machine," said Kuno. "I want to speak to you not through the wearisome Machine."

"Oh, hush!" said his mother, vaguely shocked. "You mustn't say anything against the Machine."

She prefers social distancing and giving her online lecture on Music During the Australian Period to an unseen armchair audience who lap-up abstract historical information that has absolutely no relevance to their actual subterranean lives beyond being an illusory distraction from their hollowed-out existence (not dissimilar to lectures under lockdown, maybe).

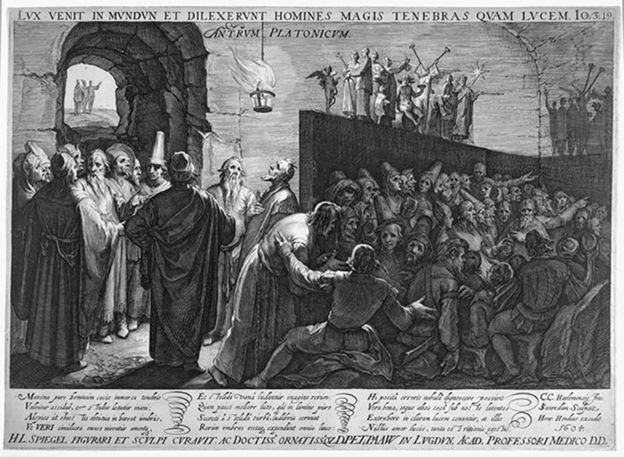

I won't say any more about what happens - it is a very short story that can be read in under an hour - other than to mention it is basically a machine-age take on Plato's The Allegory of the Cave.

TRUSTEES OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM

TRUSTEES OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM

The Machine (or internet for us) is the airless, sunless, solitary cave in which we exist, the information it imparts the shadows on the wall.

EM Forster published the story between A Room with a View (1908) and Howard's End (1910), two novels in which he explores similar philosophical themes around inner and outer worlds, truth and pretence.

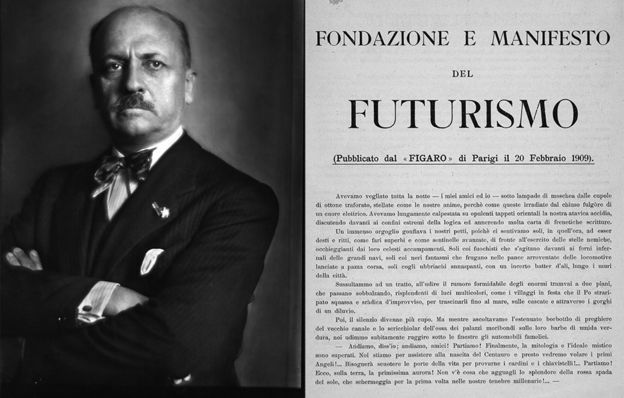

The Machine Stops first appeared in the Oxford and Cambridge Review in the same year as Filippo Tommaso Marinetti published his furious Futurist Manifesto in Le Figaro newspaper.

The Italian poet was arguing for the very opposite to Forster's prophetic parable.

Marinetti embraced the machine, arguing that a speeding car was far more beautiful than an ancient Greek sculpture. The past was a dead weight that needed destroying to make way for the future.

ALAMY

ALAMY

GETTY/SOTHEBY'S

GETTY/SOTHEBY'S

He would have liked Vashti, who, when travelling by airship to see Kuno, pulled down her blind over Greece because that was no place to find ideas - an ironic joke by Forster given the idea for his story came from Plato's Athens.

That's about it for jokes in a novella where there really is no such thing as community, or direct experience, and it is impossible to get away from the constant hum of the machine without asking the Central Committee for an Egression-permit to go outside. At which point you strap on a respirator and take your chances in the real world.

As the man on the radio said, it's prescient. And very, very good.

Recent reviews by Will Gompertz

- Who's Joe Rogan and is his podcast really worth $100m? ★★★☆☆

- Revelations about Rembrandt's masterpiece captured on camera ★★★★★

- Self-taught artist gets top prize: A worthy winner? ★★★☆☆

Follow Will Gompertz on Twitter

Lam Thuy Vo is a reporter for BuzzFeed News and is based in New York.

Lam Thuy Vo is a reporter for BuzzFeed News and is based in New York.