Stemming the methane leaks from landfills, oil fields, natural gas pipelines and more is one of the most powerful levers we have to quickly slow global warming. New satellites are bolstering this urgent mission by pinpointing emitters of this potent greenhouse gas from space.

A computer rendering of a methane-sensing satellite to be launched in 2023 by Carbon Mapper, a U.S. public-private partnership. CARBON MAPPER / PLANET

BY CHERYL KATZ • JUNE 15, 2021

The threat was invisible to the eye: tons of methane billowing skyward, blown out by natural gas pipelines snaking across Siberia. In the past, those plumes of potent greenhouse gas released by Russian petroleum operations last year might have gone unnoticed. But armed with powerful new imaging technology, a methane-hunting satellite sniffed out the emissions and tracked them to their sources.

Thanks to rapidly advancing technology, a growing fleet of satellites is now aiming to help close the valve on methane by identifying such leaks from space. The mission is critical, with a series of recent reports sounding an increasingly urgent call to cut methane emissions.

While shorter-lived and less abundant than carbon dioxide, methane is much more powerful at trapping heat, making its global warming impact more than 80 times greater in the short term. Around 60 percent of the world’s methane emissions are produced by human activities — with the bulk coming from agriculture, waste disposal, and fossil fuel production. Human-caused methane is responsible for at least 25 percent of today’s global warming, the Environmental Defense Fund estimates. Stanching those emissions, a new Global Methane Assessment by the United Nations Environmental Programme stresses, is the best hope for quickly putting the brakes on warming.

“It’s the most powerful lever we have for reducing warming and all the effects that come with climate change over the next 30 years,” said Drew Shindell, an earth sciences professor at Duke University and lead author on the UN report. Scientists stress that major reductions in both carbon dioxide and methane are critical for averting extreme climate change. “It is not a substitute for reducing CO2, but a complement,” Shindell said.

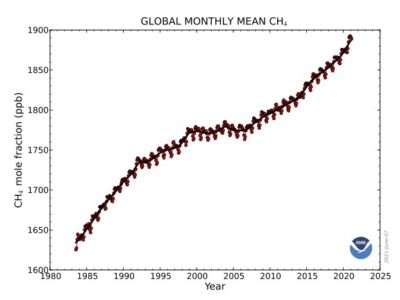

Atmospheric methane levels surged over the last half-decade. 2020 saw the biggest one-year jump on record.

Nearly half of the roughly 380 million metric tons of methane released by human activities annually can be cut this decade with available and largely cost-effective methods, according to the UN assessment. Doing so would stave off nearly 0.3 degrees C of warming by the 2040s — buying precious time to get other greenhouse gas emissions under control. The easiest gains can be made by fixing leaky pipelines, stopping deliberate releases such as venting unwanted gas from drilling rigs, and other actions in the oil and gas industry, the UN report says. Capturing fumes from rotting materials in landfills and squelching the gassy belches of ruminant livestock will also help.

ALSO ON YALE E360

What is causing the recent rise in methane emissions? Read more.

For now, though, the trend is running in the opposite direction: The methane concentration in Earth’s atmosphere has been surging over the past half-decade, the NOAA Annual Greenhouse Gas Index shows. And despite the pandemic, 2020 saw the biggest one-year jump on record. The causes of the recent spike are unclear, but could include natural gas fracking, increased output from methane-producing microbes spurred by rising temperatures, or a combination of human-caused and natural forces.

All this, experts say, underscores the need to track down and plug any leaks or sources that can be controlled. Tracing emissions to their source is no easy task, however. Releases are often intermittent and easy to miss. Ground-based sensors can detect leaks in local areas, but their coverage is limited. Airplane and drone surveys are time-intensive and costly, and air access is restricted over much of the world.

That’s where a crop of recently launched and upcoming satellites with increasingly sophisticated tools comes in.

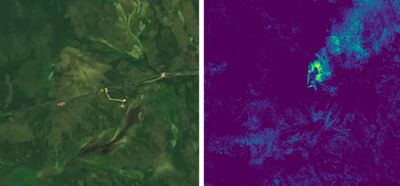

Satellite imagery shows a Russian gas pipeline (left) and highlights huge amounts of methane (right) being emitted from the pipeline on September 6, 2019. KAYRROS AND MODIFIED COPERNICUS DATA, 2019

A cluster of satellites launched by national space agencies and private companies over the last five years have greatly sharpened our view of what methane is being leaked from where. In the next couple of years, new satellite projects are headed for launch — including Carbon Mapper, a public-private partnership in California, and MethaneSAT, a subsidiary of the Environmental Defense Fund — that will help fill in the picture with unprecedented range and detail. These efforts, experts say, will be crucial not just for spotting leaks but also developing regulations and guiding enforcement — both of which are sorely lacking.

“You can’t mitigate what you can’t measure,” said Cassandra Ely, director of MethaneSAT.

Earlier satellites, such as the Japan Aerospace Exploration’s GOSAT launched in 2009, were able to detect methane, yet their resolution wasn’t good enough to identify specific sources.

But satellite technology is now advancing rapidly, boosting resolution, shrinking size, and gaining a host of cutting-edge capabilities. Powerful new eyes in space include the European Space Agency’s Sentinel 5P (launched in 2017), the Italian Space Agency’s PRISMA (launched 2019), and systems operated by private Canadian company GHGSat (with satellites launched in 2016, 2020 and 2021). Companies like French Kayrros are using artificial intelligence to enhance satellite imaging, paired with air and ground data, to provide detailed methane reports.

At any given time, there are about 100 high-volume methane leaks around the world.

In the past year, methane-hunting satellites have made a number of concerning discoveries. Among them: Despite the pandemic, methane emissions from oil and gas operations in Russia rose 32 percent in 2020. Satellites also observed sizeable releases from gas pipelines in Turkmenistan, a landfill in Bangladesh, a natural gas field in Canada, and coal mines in the U.S. Appalachian Basin.

At any given time, according to Kayrros, there are about 100 high-volume methane leaks around the world, along with a mass of smaller ones that add significantly to the total. Targeting emitters on a global scale from space, the European Space Agency says, provides “an important new tool to combat climate change.”

Now, Carbon Mapper is developing what it promises will be the most sensitive and precise tool for spotting point sources yet. The project aims to launch two satellites in 2023, eventually growing to a constellation of up to 20 that will provide near-constant methane and CO2 monitoring around the globe. Partners include NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, the California Air Resources Board, private satellite company Planet, and universities and nonprofits, with funding from major private donors, including Bloomberg Philanthropies.

The impetus is the current global monitoring gap, said Riley Duren, a remote-sensing scientist at the University of Arizona and Carbon Mapper CEO. “There’s no single organization that has the necessary mandate and resources and institutional culture to deliver an operational monitoring system for greenhouse gases,” Duren said. “At least not in the time frame that we need.” Duren likens Carbon Mapper to the U.S. National Weather Service, as it will provide an “essential public service” with its routine, sustained monitoring of greenhouse gases.

Cows at a dairy farm in Merced, California. Gassy belches of ruminant livestock are a significant source of methane. MARMADUKE ST. JOHN / ALAMY

The project’s main focus is to find super emitters, Duren said. He and colleagues conducted a previous study via methane-sensing airplane surveys of oil and gas operations, landfills, wastewater treatment, and agriculture in California that found that nearly half of the state’s methane output came from less than 1 percent of its infrastructure. Landfills produced the biggest share of the state’s overall emissions in that survey, followed by agriculture and then oil and gas.

The survey pointed out the need to “scale that up and operationalize it globally by going into space,” Duren said. The orbiters will employ “hyperspectral” spectrometers designed by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, which the project’s website says will provide “unparalleled sensitivity, resolution and versatility.” The minifridge-sized satellites will be able to target a release to within 30 meters, precise enough to identify the exact piece of equipment that’s leaking.

When emissions are detected, subscribers to a rapid alert service will be notified within 24 hours by Planet, a private, San Francisco-based satellite operator that will build and manage the Carbon Mapper satellites.

The satellites will enhance the California Air Resources Board’s monitoring with wider and more frequent coverage, said Jorn Herner, who heads the board’s emissions monitoring program. Monitoring now is done once a quarter, he said. When the full constellation of Carbon Mapper satellites is deployed, that will increase to near-daily. “You just have a much better handle on what’s going on [and] when,” Herner said, “and you’ll be able to address any leaks more quickly.”

The global policies needed to do something about methane emissions aren’t yet in place.

Also joining the orbiting hunters will be MethaneSAT, a satellite that will scan wider areas — up to 200 kilometers in a swath, albeit with lower, 100-meter, resolution. This program uses a special algorithm that generates flux rates from the satellite data. “So instead of just getting a picture or a snapshot, you actually get more of a movie,” said MethaneSAT director Ely. That’s a first for satellite-based sensing and a boon to tracing wind-blown plumes back to their source, she said.

MethaneSAT will focus on the global oil and gas industry and aims to be sensitive enough to reveal the multitude of small methane releases that can account for the majority of emissions, Ely says. The findings will be made available to industry operators, regulators, investors and the public in near-real time. The data, she said, will help “prioritize what makes the most sense in terms of emissions reductions and mitigation.”

Yet while the world’s ability to hunt down methane emitters is growing, the global policies needed to do something about it aren’t yet in place.

Much of the current approach to dialing back methane is dependent on voluntary actions by the oil and gas industry. Satellites can help with that, UN report lead author Shindell and others said, by identifying leaks that, if stopped, will save or make those companies money. “If you capture the methane instead of letting it escape to the atmosphere, you have something quite useful,” Shindell said. “So, there’s a nice financial incentive not to waste it.” But if gas prices aren’t high enough, operators can feel it’s not worth the expense and effort to find, stem, and utilize runaway emissions — making rules and fees a necessary part of the picture.

“Having stronger regulations is really key,” Shindell said.

The global monthly average concentration of methane in the atmosphere. NOAA

Regulations on methane emissions today are a patchwork of local and national measures, with few international agreements that set specific targets, the UN report points out. In the United States, state policies range from fairly strict controls in some states, such as California and Colorado, to little enforcement in Texas and others. The U.S. Senate recently moved to reinstate methane emissions rules for the oil and gas industry that the Trump administration had rescinded; Congress is expected to vote on that action later this month. A Senate bill proposed in March would levy a fee on the industry’s methane output. And the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency just issued a plan to cap methane and other air pollutants from landfills.

The European Union is currently working on new regulations for emissions from the energy sector. However, other big emitters, such as Russia, have almost no methane-restricting policies in effect, according to the International Energy Agency analysis. Ahead of the UN climate change conference in November, the International Energy Forum this month launched its Methane Measurement Methodology Project, giving member nations access to data from the Sentinel 5P satellite along with analyses from Kayrros, to get a better handle on emissions from the energy industry.

Data from satellites could provide a useful political lever to compel countries to crack down on their emissions, scientists say. Precise measurements on Russian pipeline leaks, for example, could enable the EU, a major customer for Russian oil and gas, to impose border tariffs based on the emissions from production and transport. Better monitoring could also aid recent actions by shareholders and courts compelling major fossil fuel corporations to rein in their greenhouse gas emissions.

ALSO ON YALE E360

Methane detectives: Can a wave of new technology slash natural gas leaks? Read more.

Whatever measures come into effect, policymakers and regulators will need eyes in space to keep tabs on whether those rules are working, and to pinpoint violators and incentivize change.

Said Carbon Mapper’s Duren: “There are many uses for just making the invisible visible.”

Cheryl Katz is a Northern California-based freelance science writer covering climate change, earth sciences, natural resources, and energy. Her articles have appeared in National Geographic, Scientific American, Eos and Hakai Magazine, among other publications.

Yale Environment 360

Published at the Yale School of the Environment