New research suggests that a psychological concept known as “the need for chaos” plays a bigger role than partisanship and ideology in the sharing of conspiracy theories on the internet. The study, published in Research & Politics, indicates that individuals driven by a desire to disrupt and challenge established systems are more inclined to share conspiracy theories.

The study was authored by Christina Farhart (assistant professor, Carleton College), Erin Fitz (PhD candidate, Colorado State University), Joanne Miller (professor, University of Delaware), and Kyle Saunders (professor, Colorado State University).

The authors wanted to explore three specific motivations behind the sharing of conspiracy theories: motivated sharing (sharing to bolster their or their group’s beliefs), sounding the alarm (sharing to generate collective action against a political outgroup due to feelings of losing), and the need for chaos (sharing to disrupt the political system regardless of partisanship or belief).

“We were motivated by prior research that revealed the relationship between the need for chaos and willingness to share conspiracy theories on social media,” the researchers told PsyPost.

“Although earlier work found a positive relationship between the need for chaos and sharing (and that the need for chaos superseded partisan motivations for sharing) these studies did not assess how the need for chaos affected sharing when pitted against a direct measure of conspiracy theory belief. Testing these mechanisms together is important because people who believe conspiracy theories might be more willing to share them online, but belief is not a necessary condition for sharing.”

To conduct the study, the researchers administered an original survey in December 2018 using the Lucid platform, which recruits online survey respondents in line with US Census demographics. The survey included questions about respondents’ beliefs in specific conspiracy theories and their willingness to share those conspiracy theories. A total of 3,336 respondents participated in the survey. Among them, 1,772 identified as Democrats/leaning Democrat, and 1,564 identified as Republicans/leaning Republican.

Motivated sharing was operationalized by assessing respondents’ beliefs in specific conspiracy theories and their willingness to share those conspiracy theories. The study examined how the willingness to share was related to whether the conspiracy theories aligned with respondents’ partisan identity.

For example, an item assessing Democratic-aligned conspiracy theories asked: “Some people believe Donald Trump is plotting with secret societies of white supremacists, such as the Ku Klux Klan, to take control of the United States. Others do not believe this. What do you think?”

On the other hand, an item assessing Republican-aligned conspiracy theories asked: “Some people believe that the Mueller investigation is not, in fact, an investigation into the Trump campaign’s collusion with the Russian government. Instead, they believe it is an investigation into nefarious activities, including child molestation and a variety of other crimes, perpetrated by the Clintons, Barack Obama, and other unelected people who are currently working behind the scenes to run the government. Others do not believe this. What do you think?”

To measure the “sounding the alarm” motivation, the researchers asked respondents about their perception of whether their political side was winning or losing more often on issues that mattered to them. The study explored how the feeling of being on the losing side influenced the willingness to share conspiracy theories.

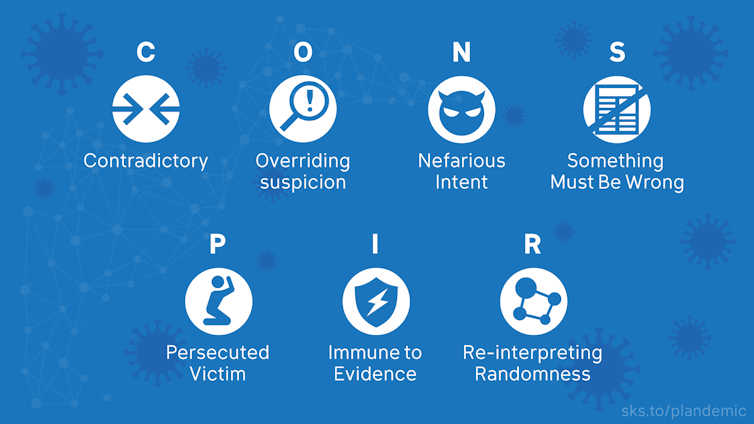

The researchers employed the eight-item Need for Chaos scale to measure individuals’ desire for extreme disruption of the established democratic system. This scale aimed to assess whether individuals with a higher need for chaos were more likely to share conspiracy theories regardless of their truth value or partisanship.

Those with a high need for chaos agree with statements such as “We cannot fix the problems in our social institutions, we need to tear them down and start over” and “I need chaos around me – it is too boring if nothing is going on.”

The researchers also included various control variables to account for other factors that might influence respondents’ willingness to share conspiracy theories, such as their strength of partisan identity, authoritarianism, trust, religiosity, education, income, gender, age, ethnicity, and race.

After controlling for these variables, the researchers confirmed that the need for chaos was positively associated with the willingness to share conspiracy theories on social media. Individuals with a higher need for chaos were more likely to express willingness to share all six conspiracy theories included in the study.

They also found that individuals who believed in a conspiracy theory were more willing to share that theory on social media. In other words, belief in a conspiracy theory was a strong predictor of the willingness to share it.

“While we also found that those with a higher need for chaos consistently expressed greater willingness to share conspiracy theories on social media, our results ultimately indicated that belief in conspiracy theories was the strongest predictor of willingness to share,” the researchers told PsyPost. “These findings contribute to our understanding of why people share conspiracy theories by suggesting that, whereas some individuals share specifically to impugn political rivals, others do so to challenge the entire political system.”

Surprisingly, loser perceptions (feeling that one’s side is losing in politics) were negatively associated with the willingness to share conspiracy theories. Those who perceived their side as currently winning more often than losing expressed greater willingness to share conspiracy theories.

Contrary to expectations, the researchers also did not find a significant relationship between partisanship or ideology and the willingness to share conspiracy theories. Partisanship and ideology did not robustly predict the sharing of either ideologically-aligned or ideologically-inconsistent conspiracy theories.

The study, like all research, also includes some caveats. The study is observational, meaning it’s based on observing and analyzing existing behaviors rather than manipulating variables. This prevents the researchers from drawing causal conclusions about the relationships between motives, beliefs, and sharing behavior.

“Altogether, our findings reveal that prior notions of partisanship and chaos as drivers of sharing hostile political rumors (including [conspiracy theories]) are perhaps more nuanced than extant literature suggests,” the researchers concluded.

The study, “By any memes necessary: Belief- and chaos-driven motives for sharing conspiracy theories on social media“, was published online August 1, 2023.

© PsyPost