CBC

Thu, August 24, 2023

A lone caibou crosses a fen in Wapusk National Park in northern Manitoba. The Cape Churchill herd, one of the most stable populations of caribou in Canada, is estimated to be comprised of 1,000 to 3,000 animals. (Matthew Van Egmond/Parks Canada - image credit)

Wildlife scientists from two provinces are using motion-activated cameras to try to discern why one caribou population in northern Manitoba appears to be stable while herds are dwindling almost everywhere else in Canada.

Since 2022, researchers from Parks Canada, the University of Saskatchewan and the Manitoba Métis Federation have been collecting images from 92 motion-activated wildlife cameras placed in and around Wapusk National Park, a protected area in northern Manitoba along the coast of Hudson Bay.

The park protects about 99 per cent of the summer calving range of the Cape Churchill caribou herd, whose population has been estimated at somewhere between 1,000 and 3,000 animals for decades.

Wapusk also protects part of the herd's spring and fall migratory routes, while their wintering grounds lie outside the park in relatively pristine forests.

Russell Turner, an ecosystems scientist for the park, said Parks Canada and its research partners are hoping to collect enough data to establish a link between habitat protection and population health.

"Almost every other caribou population in Canada is declining, and so it's unfortunate that we don't know why these caribou are stable, but it could be because of the national park and they're protected," Russell said in an interview outside Churchill, Man., earlier this month.

While the connection between protection and population may sound logical, Turner said the Cape Churchill herd is unusual. It winters in the boreal forest and summers on the tundra, rather than spending all year in one ecological zone or another.

"We have a unique type that utilizes both the woodland and barren ground," Turner said. "It's a relatively small herd in Manitoba and relatively understudied, so we know very little information about it."

Remote cameras

A caribou walks along a fen in Wapusk National Park in August 2022. This image was captured by a motion-activated wildlife camera. Researchers with Parks Canada, the University of Saskatchewan and the Manitoba Metis Federation are trying to discern migration patterns of the Cape Churchill caribou herd.

A caribou walks along a fen in Wapusk National Park in August 2022. This image was captured by a motion-activated wildlife camera. Researchers with Parks Canada, the University of Saskatchewan and the Manitoba Metis Federation are trying to discern migration patterns of the Cape Churchill caribou herd. (Ryan Brook/University of Saskatchewan)

Gathering that information is not easy. Trail cameras are not easy to install in and around Wapusk, which is bitterly cold and snowy during the winter, soggy in the summer and has no road access any time of year.

Parks Canada and its partners at the Métis Federation and the University of Saskatchewan collect images from 92 cameras mounted on posts, walking on foot to swap out batteries and memory cards at locations close to a Wapusk research camp called Nester One.

Other cameras are serviced by helicopter. Those include locations close to Cape Churchill, which is home to a sandbar dubbed "the lounge" where some of the largest male polar bears in the park congregate.

Polar bears destroyed six of the cameras in 2022. Turner knows this because the ursine offenders were caught on camera.

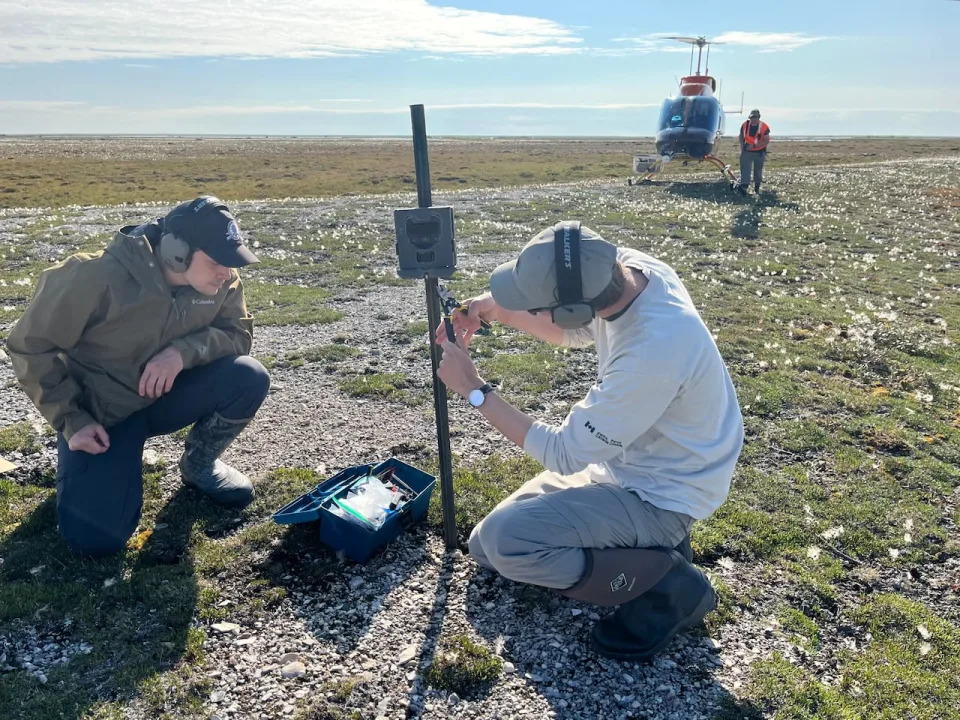

Riley Bartel of the Manitoba Metis Federation, left, and Parks Canada's Matthew Van Egmond replace the batteries and data card on a wildlife camera placed in Wapusk National Park while Parks Canada ecosystem scientist Russell Turner watches for polar bears. This team replaced the batteries and cards on 28 cameras in one day, flying between sites by helicopter to both speed the process and minimize the chance of a polar-bear encounter.More

Riley Bartel of the Manitoba Metis Federation, left, and Parks Canada's Matthew Van Egmond replace the batteries and data card on a wildlife camera placed in Wapusk National Park while Parks Canada ecosystem scientist Russell Turner watches for polar bears. This team replaced the batteries and cards on 28 cameras in one day, flying between sites by helicopter to both speed the process and minimize the chance of a polar-bear encounter. (Bartley Kives/CBC News)

The cameras have also captured images of grizzly bears, Arctic foxes, 25 species of birds and errant scientists who walked in front of the motion sensors. But the vast majority of the roughly 68,000 images collected during the first year of the project involved caribou.

"One of the interesting patterns that we can kind of see is that there's really not much utilizing the park or moving much in the winter. You kind of see all species showing up in May and June, and really only some wolves and foxes in the winter," Turner said.

The cameras also end up with closeups from animals that inspect the cameras as well as posterior views,

"We definitely get a lot of butt photos, a lot of caribou walking away from the camera," Turner quipped.

The motion-activated cameras also capture images of other animals, including foxes, polar bears and this wolf.

The motion-activated cameras also capture images of other animals, including foxes, polar bears and this wolf. (Ryan Brook/University of Saskatchewan)

The researchers are also hoping to use the cameras to demonstrate what traditional knowledge has maintained for years: That caribou prefer to migrate along dry beach ridges rather than slog it out on soggy fens.

"We're trying to use these cameras to learn when they're at different locations, what habitat they're using, and hopefully also be able to learn about their their predators and some of their activity in the environment as well," Turner said.

Ryan Brook, a wildlife ecologist at the University of Saskatchewan, said it's interesting to see where timber wolves are relative to their caribou prey.

"They den mostly in the forested areas to the south end of the park, but they they will make daily or or longer-term trips further north where the caribou are," he said at Nester One.

The motion sensor on this wildlife camera bears puncture marks from a polar bear. This camera, which was placed at Cape Churchill - a summer gathering place for adult male polar bears - had to be replaced.

The motion sensor on this wildlife camera bears puncture marks from a polar bear. This camera, which was placed at Cape Churchill — a summer gathering place for adult male polar bears — had to be replaced. (Bartley Kives/CBC)

Riley Bartel, conservation coordinator for the Manitoba Métis Federation, said his organization hopes to use data from the cameras to support the creation of an Indigenous protected area for for the Cape Churchill caribou herd southwest of Wapusk.

Such a move would require provincial co-operation, but Parks Canada is already on board.

"Their summer grounds are protected, but if the wintering grounds could also be protected that that just helps preserve this species even more," said Bartel, also speaking at Nester One.

Ultimately, Turner hopes to demonstrate habitat protection is directly connected to the health of the caribou population, a seemingly obvious link that nonetheless has yet to be demonstrated by science.

"I think that would be a huge benefit for potentially new protected parks," he said.

A polar bear rests on the coast of Wapusk. It was one of 15 bears spotted from the air during one day of wildlife-camera servicing by Parks Canada staff.

A polar bear rests on the coast of Wapusk. It was one of 15 bears spotted from the air during one day of wildlife-camera servicing by Parks Canada staff. (Matthew Van Egmond/Parks Canada)

No comments:

Post a Comment