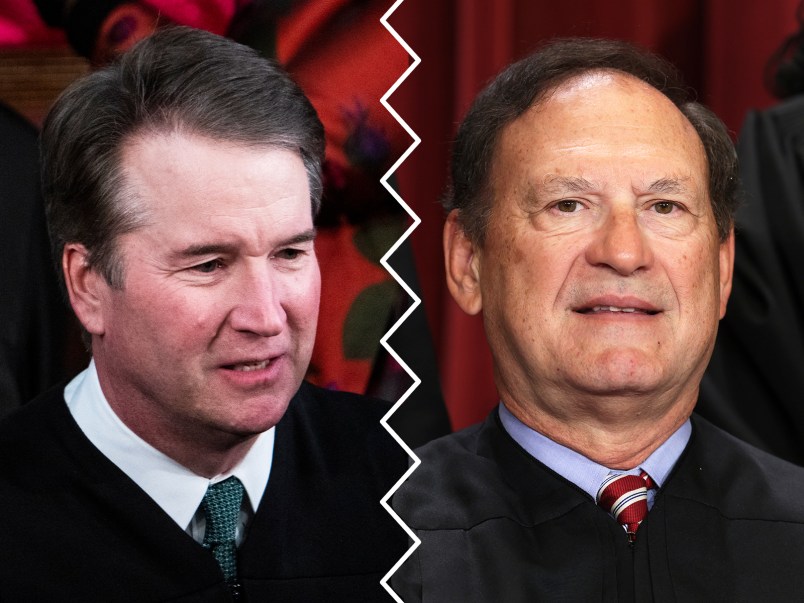

Justices Brett Kavanaugh and Samuel Alito. TPM Illustration/Getty Images

By Kate Riga

|

February 26, 2024

The Supreme Court on Monday heard arguments centered on what’s become a cottage industry on the right: crafting legal and statutory challenges to social media platforms’ content moderation practices.

These cases grew out of endless conservative complaints about “shadow banning” and “censorship,” platforms’ policies that conservatives claim are single-mindedly aimed at tamping down right-wing influence. It’s a natural outgrowth of the Republican Party’s grievance politics, and ramped up after the COVID-19 pandemic, when anti-vaxxer content on social media became a huge point of contention.

Monday’s arguments centered on laws out of Florida and Texas that would guide and restrict the platforms’ content moderation decisions, and demand platforms provide individualized explanations for those decisions to the affected users. The oral arguments over challenges to the pair of laws are just the first on the Court’s docket this term to deal with these issues; another challenging the Biden administration’s practice of flagging misinformation to tech companies will be argued next month.

The Florida law in particular is quite sprawling, including provisions that the platforms cannot “censor” any “journalistic enterprise” or “willfully deplatform a candidate” for office. It also potentially extends beyond the traditional social media sites, prompting many justices to ask how the law may be applied to messaging carriers like Gmail or marketplaces like Etsy.

Questions about the breadth of the legislation consumed much of the hearings, with some justices clearly mulling remanding at least the Florida case to address the further flung applications.

But perhaps the most interesting moments in the proceedings arose when the right-wing justices’ long-held reflexive positioning came into conflict with a newer strain of their ideology: old-school, free market, pro-business conservatism vs. the new age, Trumpian culture wars. The Court’s Republican appointees are a microcosm of the same dynamic playing out in the party at large, as the old guard fights to retain relevance amid the influx of MAGA politicians and their new, often vindictive, priorities.

Justice Samuel Alito was trying to press U.S. Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar into admitting that a hypothetical private law school saying that any student who expresses support for Israel in the war with Hamas will be expelled is “censorship.”

She pushed back that the “semantics” — censorship, moderation — matter much less for these cases than what’s being regulated.

“The particular word that you use matters only to the extent that some may want to resist the Orwellian temptation to recategorize offensive conduct in seemingly bland terms,” he quipped in response.

It’s typical Alito, using a hypothetical to make his views clear: that the social media companies are “censoring” right-wing viewpoints, and using terms like “content moderation” or “editorial discretion” to obscure that. This is the culture warrior position — that red states can and should use government to punish companies acting in ways they don’t like. For some on the right, especially of the MAGA persuasion, these companies are no longer cloaked by the shibboleth that corporations are benevolent, economic drivers who deserve the benefit of the doubt and unregulated freedom. Call it the Ron DeSantis thesis.

A rebuttal came from an unlikely place a few minutes later: Justice Brett Kavanaugh.

“I just want to follow-up on Justice Alito’s questions,” he said. “I think he asked a good, thought provoking, important question, and used the term ‘Orwellian.’ When I think of Orwellian, I think of the state, not the private sector, not a private individual.”

“Maybe people have different conceptions of Orwellian,” he added, before pointing to “the state taking over the media like in some other countries.”

And here’s our old-school Republican position. Private entities are trustworthy with power, or at least more trustworthy than the tyrannical government trying to regulate them.

Chief Justice Roberts, throughout, hewed to Kavanaugh’s camp.

“I wonder, since we’re talking about the First Amendment, whether our first concern should be with the state regulating what we have called the modern public square,” he said the first time he spoke.

Justice Clarence Thomas, unsurprisingly, seemed to side with Alito, his natural ally. While noting that the attorney for the social media platforms called it “censoring” if the government does it and “content moderation” if done by a private party, he snarked: “These euphemisms elude me.”

For all but the most dedicated culture warriors, the Florida and Texas laws may ultimately prove too sprawling for them to get behind. The justices spent much of the arguments debating the knock-on effects of the laws and of questioning how, if one of these tech platforms chose to opt out of serving Florida or Texas rather than complying with the law, it could even manage to do it.

But the issue isn’t going away. As long as a sizeable chunk of the right-wing legal world cares greatly about punishing companies it views as enemies — and as long as the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals happily rubber stamps these suits on the way up — the pro-business justices and the culture warriors on the Supreme Court will continue to be locked into their internecine battles.

“[To whom] do you want to leave the judgment about who can speak or who cannot speak on these platforms?” Roberts asked. “Do you want to leave it with the government or the state, or leave it with the platforms? The First Amendment has a thumb on the scale when that question is asked.”

Kate Riga (@Kate_Riga24) is a D.C. reporter for TPM and cohost of the Josh Marshall Podcast.

|

February 26, 2024

The Supreme Court on Monday heard arguments centered on what’s become a cottage industry on the right: crafting legal and statutory challenges to social media platforms’ content moderation practices.

These cases grew out of endless conservative complaints about “shadow banning” and “censorship,” platforms’ policies that conservatives claim are single-mindedly aimed at tamping down right-wing influence. It’s a natural outgrowth of the Republican Party’s grievance politics, and ramped up after the COVID-19 pandemic, when anti-vaxxer content on social media became a huge point of contention.

Monday’s arguments centered on laws out of Florida and Texas that would guide and restrict the platforms’ content moderation decisions, and demand platforms provide individualized explanations for those decisions to the affected users. The oral arguments over challenges to the pair of laws are just the first on the Court’s docket this term to deal with these issues; another challenging the Biden administration’s practice of flagging misinformation to tech companies will be argued next month.

The Florida law in particular is quite sprawling, including provisions that the platforms cannot “censor” any “journalistic enterprise” or “willfully deplatform a candidate” for office. It also potentially extends beyond the traditional social media sites, prompting many justices to ask how the law may be applied to messaging carriers like Gmail or marketplaces like Etsy.

Questions about the breadth of the legislation consumed much of the hearings, with some justices clearly mulling remanding at least the Florida case to address the further flung applications.

But perhaps the most interesting moments in the proceedings arose when the right-wing justices’ long-held reflexive positioning came into conflict with a newer strain of their ideology: old-school, free market, pro-business conservatism vs. the new age, Trumpian culture wars. The Court’s Republican appointees are a microcosm of the same dynamic playing out in the party at large, as the old guard fights to retain relevance amid the influx of MAGA politicians and their new, often vindictive, priorities.

Justice Samuel Alito was trying to press U.S. Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar into admitting that a hypothetical private law school saying that any student who expresses support for Israel in the war with Hamas will be expelled is “censorship.”

She pushed back that the “semantics” — censorship, moderation — matter much less for these cases than what’s being regulated.

“The particular word that you use matters only to the extent that some may want to resist the Orwellian temptation to recategorize offensive conduct in seemingly bland terms,” he quipped in response.

It’s typical Alito, using a hypothetical to make his views clear: that the social media companies are “censoring” right-wing viewpoints, and using terms like “content moderation” or “editorial discretion” to obscure that. This is the culture warrior position — that red states can and should use government to punish companies acting in ways they don’t like. For some on the right, especially of the MAGA persuasion, these companies are no longer cloaked by the shibboleth that corporations are benevolent, economic drivers who deserve the benefit of the doubt and unregulated freedom. Call it the Ron DeSantis thesis.

A rebuttal came from an unlikely place a few minutes later: Justice Brett Kavanaugh.

“I just want to follow-up on Justice Alito’s questions,” he said. “I think he asked a good, thought provoking, important question, and used the term ‘Orwellian.’ When I think of Orwellian, I think of the state, not the private sector, not a private individual.”

“Maybe people have different conceptions of Orwellian,” he added, before pointing to “the state taking over the media like in some other countries.”

And here’s our old-school Republican position. Private entities are trustworthy with power, or at least more trustworthy than the tyrannical government trying to regulate them.

Chief Justice Roberts, throughout, hewed to Kavanaugh’s camp.

“I wonder, since we’re talking about the First Amendment, whether our first concern should be with the state regulating what we have called the modern public square,” he said the first time he spoke.

Justice Clarence Thomas, unsurprisingly, seemed to side with Alito, his natural ally. While noting that the attorney for the social media platforms called it “censoring” if the government does it and “content moderation” if done by a private party, he snarked: “These euphemisms elude me.”

For all but the most dedicated culture warriors, the Florida and Texas laws may ultimately prove too sprawling for them to get behind. The justices spent much of the arguments debating the knock-on effects of the laws and of questioning how, if one of these tech platforms chose to opt out of serving Florida or Texas rather than complying with the law, it could even manage to do it.

But the issue isn’t going away. As long as a sizeable chunk of the right-wing legal world cares greatly about punishing companies it views as enemies — and as long as the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals happily rubber stamps these suits on the way up — the pro-business justices and the culture warriors on the Supreme Court will continue to be locked into their internecine battles.

“[To whom] do you want to leave the judgment about who can speak or who cannot speak on these platforms?” Roberts asked. “Do you want to leave it with the government or the state, or leave it with the platforms? The First Amendment has a thumb on the scale when that question is asked.”

Kate Riga (@Kate_Riga24) is a D.C. reporter for TPM and cohost of the Josh Marshall Podcast.

No comments:

Post a Comment