SPACE/COSMOS

Africa sets up Cairo-based Space Agency

Africa has launched its first continent-wide space agency, headquartered in Cairo, to coordinate national space programmes and expand access to climate and weather data at a time of rising environmental vulnerability and declining foreign support, Bloomberg reports.

The African Space Agency, operating under the African Union, officially began operations last month and is currently recruiting for key technical and administrative roles. Its primary mandate is to unify fragmented space initiatives across member states, launch satellites, and establish a data-sharing infrastructure to improve forecasting and disaster preparedness.

“Space activities on the continent have been happening in a very fragmented fashion,” said Meshack Kinyua, a space engineer and veteran of Africa’s space policy community who now oversees capacity-building at the new agency, cited by Bloomberg. “The African Space Agency brings a coordination mechanism and economies of scale — it puts all members of the African Union at an equal level in terms of gathering data that they can access according to their needs.”

The move comes as the availability of high-resolution climate and weather data becomes increasingly restricted, particularly following cuts to US-led development assistance. Under the Trump administration, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) ended funding for 80% of its projects, including SERVIR, a key initiative in partnership with NASA that supported climate monitoring and disaster response in developing countries.

The loss of such programmes has made it more difficult for African governments to access the data required to issue weather alerts or build accurate long-term climate models. “We need to ensure that African satellites can improve measurements and fill data gaps,” Kinyua said. “These gaps will always be there, and we need to fill some of them ourselves, and engage with other agencies.”

Africa remains the most climate-vulnerable region globally, despite contributing relatively little to global carbon emissions. Limited weather infrastructure has left many countries unable to track extreme weather events or prepare for long-term environmental shifts.

The new agency aims to scale up local successes, including early warning systems for fishermen in West Africa and communities along the Congo River basin. “The African Space Agency is a step toward changing that,” Kinyua said.

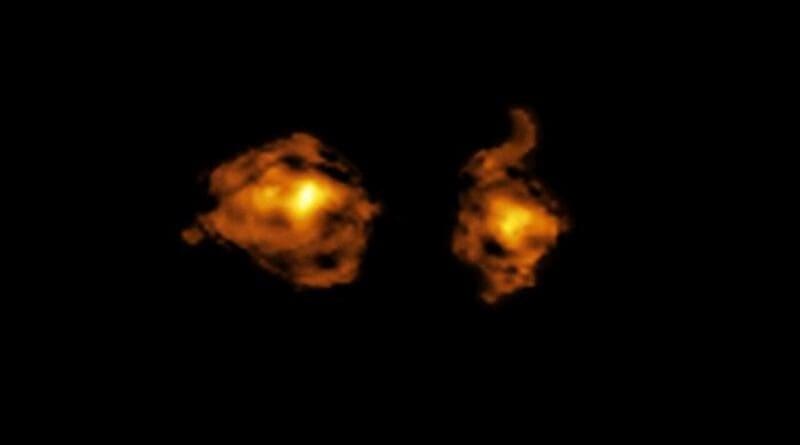

‘Cosmic Joust’: Astronomers Observe Pair Of Galaxies In Deep-Space Battle

This image, taken with the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), shows the molecular gas content of two galaxies involved in a cosmic collision. The one on the right hosts a quasar –– a supermassive black hole that is accreting material from its surroundings and releasing intense radiation directly into the other galaxy. Credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO)/S. Balashev and P. Noterdaeme et al.

Astronomers have witnessed for the first time a violent cosmic collision in which one galaxy pierces another with intense radiation. Their results, published today in Nature, show that this radiation dampens the wounded galaxy’s ability to form new stars. This new study combined observations from both the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope (ESO’s VLT) and the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), revealing all the gory details of this galactic battle.

In the distant depths of the Universe, two galaxies are locked in a thrilling war. Over and over, they charge towards each other at speeds of 500 km/s on a violent collision course, only to land a glancing blow before retreating and winding up for another round. “We hence call this system the ‘cosmic joust’,” says study co-lead Pasquier Noterdaeme, a researcher at the Institut d’Astrophysique de Paris, France, and the French-Chilean Laboratory for Astronomy in Chile, drawing a comparison to the medieval sport. But these galactic knights aren’t exactly chivalrous, and one has a very unfair advantage: it uses a quasar to pierce its opponent with a spear of radiation.

Quasars are the bright cores of some distant galaxies that are powered by supermassive black holes, releasing huge amounts of radiation. Both quasars and galaxy mergers used to be far more common, appearing more frequently in the Universe’s first few billion years, so to observe them astronomers peer into the distant past with powerful telescopes. The light from this ‘cosmic joust’ has taken over 11 billion years to reach us, so we see it as it was when the Universe was only 18% of its current age.

“Here we see for the first time the effect of a quasar’s radiation directly on the internal structure of the gas in an otherwise regular galaxy,” explains study co-lead Sergei Balashev, who is a researcher at the Ioffe Institute in St Petersburg, Russia. The new observations indicate that radiation released by the quasar disrupts the clouds of gas and dust in the regular galaxy, leaving only the smallest, densest regions behind. These regions are likely too small to be capable of star formation, leaving the wounded galaxy with fewer stellar nurseries in a dramatic transformation.

But this galactic victim isn’t all that is being transformed. Balashev explains: “These mergers are thought to bring huge amounts of gas to supermassive black holes residing in galaxy centres.” In the cosmic joust, new reserves of fuel are brought within reach of the black hole powering the quasar. As the black hole feeds, the quasar can continue its damaging attack.

This study was conducted using ALMA and the X-shooter instrument on ESO’s VLT, both located in Chile’s Atacama Desert. ALMA’s high resolution helped the astronomers clearly distinguish the two merging galaxies, which are so close together they looked like a single object in previous observations. With X-shooter, researchers analysed the quasar’s light as it passed through the regular galaxy. This allowed the team to study how this galaxy suffered from the quasar’s radiation in this cosmic fight.

Observations with larger, more powerful telescopes could reveal more about collisions like this. As Noterdaeme says, a telescope like ESO’s Extremely Large Telescope “will certainly allow us to push forward a deeper study of this, and other systems, to better understand the evolution of quasars and their effect on host and nearby galaxies.”

Eurasia Review

Eurasia Review is an independent Journal that provides a venue for analysts and experts to disseminate content on a wide-range of subjects that are often overlooked or under-represented by Western dominated media.

‘Pinballs in a cosmic arcade’: New study suggests how wide-orbit planets form, supporting existence of Planet Nine

Rice University

image:

André Izidoro, assistant professor of Earth, environmental and planetary sciences at Rice University.

view moreCredit: Alex Becker/Rice University

In the cold, dark outskirts of planetary systems far beyond the reach of the known planets, mysterious gas giants and planetary masses silently orbit their stars — sometimes thousands of astronomical units (AU) away. For years, scientists have puzzled over how these “wide-orbit” planets, including the elusive Planet Nine theorized in our own solar system, could have formed. Now, a team of astronomers may have finally found the answer.

In a new study published in Nature Astronomy, researchers from Rice University and the Planetary Science Institute used complex simulations to show that wide-orbit planets are not anomalies but rather natural by-products of a chaotic early phase in planetary system development. This phase occurs while stars are still packed tightly in their birth clusters and planets are jostling for space in turbulent, crowded systems.

“Essentially, we’re watching pinballs in a cosmic arcade,” said André Izidoro, assistant professor of Earth, environmental and planetary sciences at Rice and the study’s lead author. “When giant planets scatter each other through gravitational interactions, some are flung far away from their star. If the timing and surrounding environment are just right, those planets don’t get ejected, but rather they get trapped in extremely wide orbits.”

For the study, the team ran thousands of simulations involving different planetary systems embedded in realistic star cluster environments. They modeled a variety of conditions, from systems like our solar system with a mix of gas and ice giants to more exotic systems including those with two suns. What they discovered was a recurring pattern: Planets were frequently pushed into wide, eccentric orbits by internal instabilities, then stabilized by the gravitational influence of nearby stars in the cluster.

“When these gravitational kicks happen at just the right moment, a planet’s orbit becomes decoupled from the inner planetary system,” said study co-author Nathan Kaib, senior scientist and senior education and communication specialist at the Planetary Science Institute. “This creates a wide-orbit planet — one that’s essentially frozen in place after the cluster disperses.”

The researchers define wide-orbit planets as having semimajor axes between 100 and 10,000 AU — distances that place them far beyond the reach of most traditional planet-forming disks.

The findings could help explain the long-standing mystery of Planet Nine, a hypothetical planet believed to orbit our sun at a distance of 250 to 1,000 AU. Though it has never been directly observed, the odd orbits of several trans-Neptunian objects hint at its presence.

“Our simulations show that if the early solar system underwent two specific instability phases — the growth of Uranus and Neptune and the later scattering among gas giants — there is up to a 40% chance that a Planet Nine-like object could have been trapped during that time,” Izidoro said.

Interestingly, the study also ties wide-orbit planets to the growing population of free-floating, or “rogue,” planets — worlds ejected from their systems entirely.

“Not every scattered planet is lucky enough to get trapped,” Kaib said. “Most end up being flung into interstellar space. But the rate at which they get trapped gives us a connection between the planets we see on wide orbits and those we find wandering alone in the galaxy.”

This concept of “trapping efficiency” — the likelihood that a scattered planet remains bound to its star — is central to the study. The researchers found that solar system-like systems are particularly efficient with trapping probabilities of 5-10%. Other systems, like those composed only of ice giants or circumbinary planets, had much lower efficiencies.

“We expect roughly one wide-orbit planet for every thousand stars,” Izidoro said. “That may seem small, but across billions of stars in the galaxy, it adds up.”

Moreover, the study identifies promising new targets for exoplanet hunters. It suggests that wide-orbit planets are most likely to be found around high-metallicity stars that already host gas giants, making these systems prime candidates for deep imaging campaigns. The researchers also noted that if Planet Nine exists, it could be discovered soon after the Vera C. Rubin Observatory becomes fully operational. With its unparalleled ability to survey the sky in depth and detail, the observatory is expected to significantly advance the search for distant solar system objects, increasing the likelihood of either detecting Planet Nine or providing the evidence needed to rule out its existence.

“As we refine our understanding of where to look and what to look for, we’re not just increasing the odds of finding Planet Nine — we’re opening a new window into the architecture and evolution of planetary systems throughout the galaxy,” Izidoro said.

Journal

Nature Astronomy

Article Title

Very-wide-orbit planets from dynamical instabilities during the stellar birth cluster phase

Article Publication Date

27-May-2025

Politecnico di Milano returns to deep space - 2028 mission to earth-grazing asteroid Apophis

Politecnico di Milano

image:

Simulated image of asteroid Apophis during its close encounter with Earth (credits: DART Lab).

view moreCredit: DART Lab - Politecnico di Milano

After Rosetta, DART and Hera, Politecnico di Milano is preparing for a return to deep space. In 2028, the university will take part in the European Space Agency’s RAMSES mission to study Apophis which is a 350-metre-wide asteroid that will pass remarkably close to Earth, just 31,000 km away, on 13 April 2029.

The DART (Deep-space Astrodynamics Research and Technology) Laboratory, part of the Department of Aerospace Science and Technology, has been selected by ESA to contribute to the RCS-1 CubeSat, which is being developed by Tyvak International. This miniature satellite will travel aboard the RAMSES probe. Led by Professors Francesco Topputo and Fabio Ferrari, the Politecnico team will be responsible for mission design, development of autonomous guidance systems, and acquisition of close-up images of the asteroid’s surface.

CubeSats are compact, low-cost satellites that deliver significant scientific and technological value. In the RAMSES mission, they will operate autonomously in the vicinity of Apophis which is a fast-moving body travelling within geostationary orbit.

Scientifically, RCS-1 will provide key insights into Apophis's physical and dynamic properties through imagery and data gathered during the flyby. CubeSat RCS-1 will serve as a test platform for new autonomous navigation algorithms developed by the Politecnico team.

RAMSES, an ESA-proposed mission, aims to rendezvous with Apophis ahead of its 2029 flyby. The probe is scheduled to arrive by February 2029 to observe the asteroid and monitor any changes caused by Earth’s gravitational pull during its close approach.

Politecnico di Milano Department of Aerospace Science and Technology’s Francesco Topputo and Fabio Ferrari said: "Being part of the Apophis mission is a tremendous honour. We are developing state-of-the-art technologies that will venture into deep space, showcasing Italian innovation in tackling unprecedented challenges.”

On 13 April 2029 Apophis will be visible from Earth with the naked eye. But observing it up close, from just 31,000 km away, will be instruments and algorithms created at the Politecnico di Milano. This marks a new milestone in Italian space exploration.

Auburn physicist honored with international “Star Dust Award” for pioneering work in dusty plasmas

AUBURN, Ala. — Professor Edward Thomas Jr., from Auburn University’s Department of Physics, has been awarded the prestigious Star Dust Award by the International Dusty Plasma Community. The award was presented at the 10th International Conference on the Physics of Dusty Plasmas (ICPD10), held at Eindhoven University of Technology in the Netherlands.

The award citation recognizes Dr. Thomas “for thirty years of stellar contributions (pioneering discoveries and inspired leadership) to the field” of dusty plasma physics—a branch of plasma science that investigates plasmas containing micrometer- or nanometer-sized particles. These complex systems are found in environments ranging from industrial processing to the rings of Saturn and interstellar space.

“I am deeply humbled to receive this recognition,” said Thomas. “This honor is truly shared with the many students, colleagues, and collaborators who have supported and enriched this journey. The dusty plasma community has been a remarkable group to grow with over the past three decades.”

Dr. Thomas has led groundbreaking research in the dynamics of magnetized dusty plasmas, including the development of novel experimental diagnostics such as Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV). His leadership was also instrumental in the construction of the Magnetized Dusty Plasma Experiment (MDPX)—a world-class facility funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) and housed at Auburn University. The MDPX is a cornerstone of the university’s Magnetized Plasma Research Laboratory (MPRL), supported by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) and the National Science Foundation (NSF).

Throughout his career, Thomas has mentored over 50 undergraduate and graduate students and guided more than a dozen students to PhDs in plasma physics. His work has received continuous support from federal science agencies including the NSF’s CAREER, Major Research Instrumentation (MRI), and EPSCoR programs.

“This award celebrates not just past achievements but a future of continued exploration,” said Thomas. “I’m incredibly grateful to Auburn University and the College of Sciences and Mathematics for their unwavering support of our research mission.”

To learn more about dusty plasmas and Dr. Thomas’s work, visit Auburn University Physics Department.

“Raindrops in the Sun’s corona”: New adaptive optics shows stunning details of our star’s atmosphere

Scientists develop new optical system that removes blur over fine-structure in the Sun’s corona, revealing clearest images to date

video:

This time-lapse video of a prominence above the solar surface reveals its rapid, fine, and turbulent restructuring with unprecedented detail. The Sun’s fluffy-looking surface is covered by “spicules”, short-lived plasma jets, whose creation is still subject of scientific debate. The streaks on the right of this image are coronal rain falling down onto the Sun’s surface. This video was taken by the Goode Solar Telescope at Big Bear Solar Observatory using the new coronal adaptive optics system Cona. The video shows the hydrogen-alpha light emitted by the solar plasma. The video is artificially colorized, yet based on the color of hydrogen-alpha light, and darker color is brighter light.

view moreCredit: Schmidt et al./NJIT/NSO/AURA/NSF

BOULDER, CO, Tuesday, May 27, 2025 – The Sun’s corona—the outermost layer of its atmosphere, visible only during a total solar eclipse—has long intrigued scientists due to its extreme temperatures, violent eruptions, and large prominences. However, turbulence in the Earth’s atmosphere has caused image blur and hindered observations of the corona. A ground-breaking recent development by scientists from the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) National Solar Observatory (NSO), and New Jersey Institute of Technology (NJIT), is changing that by using adaptive optics to remove the blur.

As published in Nature Astronomy, this pioneering ‘coronal adaptive optics’ technology has produced the most astonishing, clearest images and videos of fine-structure in the corona to date. This development will open the door for deeper insights into the corona’s enigmatic behavior and the processes driving space weather.

Most Detailed Coronal Images to Date Revealed

Funded by the NSF and installed at the 1.6-meter Goode Solar Telescope (GST), operated by NJIT’s Center for Solar-Terrestrial Research (CSTR) at Big Bear Solar Observatory (BBSO) in California, “Cona”—the adaptive optics system responsible for these new images—compensates for the blur caused by air turbulence in the Earth’s atmosphere —similar to the bumpy air passengers feel during a flight.

“The turbulence in the air severely degrades images of objects in space, like our Sun, seen through our telescopes. But we can correct for that,” says Dirk Schmidt, NSO Adaptive Optics Scientist who led the development.

Among the team’s remarkable observations is a movie of a quickly restructuring solar prominence unveiling fine, turbulent internal flows. Solar prominences are large, bright features, often appearing as arches or loops, extending outward from the Sun's surface.

A second movie replays the rapid formation and collapse of a finely structured plasma stream. “These are by far the most detailed observations of this kind, showing features not previously observed, and it’s not quite clear what they are,” says Vasyl Yurchyshyn, co-author of the study and NJIT-CSTR research professor. “It is super exciting to build an instrument that shows us the Sun like never before,” Schmidt adds.

A third movie shows fine strands of coronal rain—a phenomenon where cooling plasma condenses and falls back toward the Sun’s surface. “Raindrops in the Sun’s corona can be narrower than 20 kilometers,” NSO Astronomer Thomas Schad concludes from the most detailed images of coronal rain to date, “These findings offer new invaluable observational insight that is vital to test computer models of coronal processes.”

Another movie shows the dramatic motion of a solar prominence being shaped by the Sun’s magnetism.

A Breakthrough in Solar Adaptive Optics

The corona is heated to millions of degrees–much hotter than the Sun’s surface–by mechanisms unknown to scientists. It is also home to dynamic phenomena of much cooler solar plasma that appears reddish-pink during eclipses. Scientists believe that resolving the structure and dynamics of the cooler plasma at small scales holds a key to answering the coronal heating mystery and improving our understanding of eruptions that eject plasma into space driving space weather—i.e., the conditions in Earth's near-space environment primarily influenced by the Sun's activity (e.g., solar flares, coronal mass ejections, and the solar wind) that can impact technology and systems on Earth and in space. The precision required demands large telescopes and adaptive optics systems like the one developed by this team.

The GST system Cona uses a mirror that continuously reshapes itself 2,200 times per second to counteract the image degradation caused by turbulent air. “Adaptive optics is like a pumped-up autofocus and optical image stabilization in your smartphone camera, but correcting for the errors in the atmosphere rather than the user’s shaky hands,” says BBSO Optical Engineer and Chief Observer, Nicolas Gorceix.

Since the early 2000s, adaptive optics have been used in large solar telescopes to restore images of the Sun’s surface to their full potential, enabling telescopes to reach their theoretical diffraction limits—i.e., the theoretical maximum resolution of an optical system. These systems have since revolutionized observing the Sun’s surface, but until now, have not been useful for observations in the corona; and the resolution of features beyond the solar limb stagnated at an order of 1,000 kilometers or worse—levels achieved 80 years ago.

“The new coronal adaptive optics system closes this decades-old gap and delivers images of coronal features at 63 kilometers resolution—the theoretical limit of the 1.6-meter Goode Solar Telescope,” says Thomas Rimmele, NSO Chief Technologist who built the first operational adaptive optics for the Sun’s surface, and motivated the development.

Implications for the Future

Coronal adaptive optics is now available at the GST. “This technological advancement is a game-changer, there is a lot to discover when you boost your resolution by a factor of 10,” Schmidt says.

The team now knows how to overcome the resolution limit imposed by the Earth’s lowest region of the atmosphere—i.e., the troposphere—on observations beyond the solar limb and is working to apply the technology at the 4-meter NSF Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope, built and operated by the NSO in Maui, Hawaiʻi. The world’s largest solar telescope would see even smaller details in the Sun’s atmosphere.

“This transformative technology, which is likely to be adopted at observatories world-wide, is poised to reshape ground-based solar astronomy,” says Philip R. Goode, distinguished research professor of physics at NJIT-CSTR and former director at BBSO, who co-authored the study. “With coronal adaptive optics now in operation, this marks the beginning of a new era in solar physics, promising many more discoveries in the years and decades to come.”

The paper describing this study, titled “Observations of fine coronal structures with high-order solar adaptive optics,” is now available in Nature Astronomy.

The authors are: Dirk Schmidt (NSO), Thomas A. Schad (NSO), Vasyl Yurchyshyn (NJIT), Nicolas Gorceix (NJIT), Thomas R. Rimmele (NSO), and Philip R. Goode (NJIT).

###

Multimedia Resources

Additional visuals are available. To access high-resolution images, videos, and full caption and credit details, click here: Press Release Media Album

About the U.S. NSF National Solar Observatory

The mission of the NSF National Solar Observatory (NSO) is to advance knowledge of the Sun, both as an astronomical object and as the dominant external influence on Earth, by providing forefront observational opportunities to the research community.

NSO built and operates the world’s most extensive collection of ground-based optical and infrared solar telescopes and auxiliary instrumentation— including the NSF GONG network of six stations around the world, and the world’s largest solar telescope, the NSF Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope—allowing solar physicists to probe all aspects of the Sun, from the deep solar interior to the photosphere, chromosphere, the outer corona, and out into the interplanetary medium. These assets also provide data for heliospheric modeling, space weather forecasting, and stellar astrophysics research, putting our Sun in the context of other stars and their environments.

Besides the operation of cutting-edge facilities, the mission includes the continued development of advanced instrumentation both in-house and through partnerships, conducting solar research, and educational and public outreach. NSO is managed by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, Inc. (AURA) under a cooperative agreement with NSF. For more information, visit nso.edu.

About the Big Bear Solar Observatory

The Center for Solar-Terrestrial Research (CSTR) at New Jersey Institute of Technology (NJIT) is an international leader in ground- and space-based solar and terrestrial physics, with interest in understanding the effects of the Sun on the geospace environment. CSTR operates, along with a number of other observatories, the Big Bear Solar Observatory (BBSO).

BBSO is located on the north side of Big Bear Lake in the San Bernardino Mountains of southwestern San Bernardino County, California, approximately 75 miles East of downtown Los Angeles. BBSO has a 1.6-meter clear-aperture Goode Solar Telescope (GST), which has no obscuration in the optical train. The telescopes and instruments at the observatory are designed and employed specifically for studying the activities and phenomena of the Sun. GST was the largest and highest-resolution solar telescope in the world for ten years, and is a leading facility for solar physics research.

The NSF National Solar Observatory and BBSO have collaborated for over two decades to develop and to advance adaptive optics technologies for solar observations. The GST has been a critical facility to develop and test prototypes for the 4-meter NSF Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope, which took over as the world’s largest solar telescope in 2022. GST’s first-ever coronal adaptive optics system Cona is the latest product of this successful and pioneering collaboration. For more information, visit bbso.njit.edu.

This time-lapse movie of a solar prominence shows how plasma “dances” and twists with the Sun’s magnetic field. This video was taken by the Goode Solar Telescope at Big Bear Solar Observatory using the new coronal adaptive optics system Cona. The video shows the hydrogen-alpha light emitted by the solar plasma. The video is artificially colorized, yet based on the color of hydrogen-alpha light, and darker color is brighter light.

Coronal Rain Video [VIDEO] |

Coronal rain forms when hotter plasma in the Sun’s corona cools down and becomes denser. Like raindrops on Earth, coronal rain is pulled down to the surface by gravity. Because the plasma is electrically charged, it follows the magnetic field lines, which make huge arches/loops, instead of falling in a straight line. This time-lapse video is composed of the highest resolution images ever made of coronal rain. The scientists show in the paper that the strands can be narrower than 20 kilometers. This video was taken by the Goode Solar Telescope at Big Bear Solar Observatory using the new coronal adaptive optics system Cona. The video shows the hydrogen-alpha light emitted by the solar plasma. The video is artificially colorized, yet based on the color of hydrogen-alpha light, and darker color is brighter light.

This time-lapse movie shows the formation and collapse of a complexly shaped plasma stream traveling at almost 100 kilometers per seconds in front of a coronal loop system. This is likely the first time such a stream, which the scientists refer to as “plasmoid”, has been observed, leaving them wondering about the physical explanation of the observed dynamics. This video was taken by the Goode Solar Telescope at Big Bear Solar Observatory using the new coronal adaptive optics system Cona. The video shows the hydrogen-alpha light emitted by the solar plasma. The video is artificially colorized, yet based on the color of hydrogen-alpha light, and darker color is brighter light.

Credit

Schmidt et al./NJIT/NSO/AURA/NSF

Schmidt et al./NJIT/NSO/AURA/NSF

Journal

Nature Astronomy

Article Title

Observations of fine coronal structures with high-order solar adaptive optics

Article Publication Date

27-May-2025

Space-to-ground infrared camouflage with radiative heat dissipation

Light Publishing Center, Changchun Institute of Optics, Fine Mechanics And Physics, CAS

image:

Figure | 1 Principle for space-to-ground infrared camouflage with radiative heat dissipation.

view moreCredit: Qin, B., Zhu, H., Zhu, R. et al.

In recent years, the space industry has experienced unprecedented explosive growth, with the number of satellite launches increasing exponentially. By the end of 2023, the number of global operational spacecraft exceeded 9,850, and the annual revenue of the space economy reached a staggering $400 billion. As space technology becomes increasingly integrated into our daily lives, enhancing the stealth of high-value space objects like spacecraft to reduce the risk of detection has become a critical challenge.

Currently, space objects face ground-based detection threats primarily in the visible, infrared, and microwave bands. Visible detection is limited by bright sky backgrounds during the day, significantly reducing its effectiveness, while microwave detection, constrained by transmitting power, is mainly used for the detection of low-orbit objects. In contrast, infrared detection, benefiting from weaker background sky radiation, can achieve higher signal-to-noise ratios, posing a particularly significant threat to space objects.

Despite the advancements in infrared camouflage technologies, their effectiveness remains limited in the unique and extreme environment of space (Fig. 1). Firstly, infrared camouflage in the solar radiation bands is rarely considered. Secondly, the efficacy of current radiative heat dissipation bands is insufficient for space objects to maintain a safe temperature range (typically -20 to 70 °C), calling for more appropriate heat dissipation bands. In the space environment, both conduction and convection are inhibited, leaving thermal radiation as the sole way for heat dissipation. Finally, the extreme application scenario in space necessitates the development of camouflage materials with reduced weight and enhanced robustness.

To address these challenges, Professor Qiang Li’s team from the State Key Laboratory of Extreme Photonics and Instrumentation, College of Optical Science and Engineering, Zhejiang University, China, proposed a novel camouflage strategy for space objects in a new paper published in Light: Science & Applications. By analyzing the energy distribution across infrared bands, they determined a camouflage strategy covering the H (1.5–1.8 μm), K (2–2.4 μm), mid-wave-infrared (MWIR, 3–5 μm), and long-wave-infrared (LWIR, 8–13 μm) bands, while utilizing the very-long-wave-infrared (VLWIR, 13–25 μm) band for efficient radiative heat dissipation.

A multilayer camouflage device, composed of ZnS/GST/HfO2/Ge/HfO2/Ni, was employed to meet the camouflage and heat dissipation demands (Fig. 2a). High absorptivity (0.839/0.633) in the H/K bands minimizes the reflected signal of solar radiation and low emissivity (0.132/0.142) in the MWIR/LWIR bands suppresses the thermal radiation signal (Fig. 2b). Additionally, high emissivity (0.798) in the VLWIR band ensures efficient thermal management (Fig. 2b).

The device was attached to a satellite model and observed outdoors against the sky using infrared cameras to simulate ground-based infrared detection of space objects. Under MWIR and LWIR cameras, the exposed sections of the satellite model reached maximum radiative temperatures of 42.2°C and 45.5°C, respectively, while the sections covered with the camouflage device exhibited radiative temperatures of only 30.5°C and 21.0°C, closely matching the sky background (Fig. 2c). In H and K band infrared cameras, the signal intensity of the device decreased by 36.9% and 24.2%, respectively, compared to the bare metallic accessories (Fig. 2c). These results demonstrated the device's excellent capabilities of concealing thermal radiation and reflected signals.

To validate its radiative heat dissipation performance, the team simulated the space environment using a vacuum chamber (Fig. 3). The chamber pressure was maintained at 0.15 Pa, where convective heat transfer becomes negligible compared to radiative heat transfer, ensuring that heat dissipation occurs primarily through radiation. Liquid nitrogen was used to simulate the 3K background of space. Simultaneously, an electric heating plate was employed to heat the device, mimicking the thermal energy captured or generated during the operation of a space object. Under a heating power of 1,200 W m-², the device achieved a thermal equilibrium temperature reduction of 39.8°C compared to a reference metal film. This performance is crucial for stabilizing the temperature of space objects, highlighting the device's significant potential for thermal management in space applications.

This research, through the rational design of thin-film structures, achieved precise spectral control across multiple bands and goals. With a total thickness of only 4.25 μm, the device realized spectral regulation in five bands and three design goals, simultaneously exhibiting excellent thermal stability. “This work holds significant prospects for augmenting our capabilities in space exploration and exploitation, thereby paving the way for humanity to venture into expanded realms of habitable space.” the researchers forecast.

Journal

Light Science & Applications

Article Title

Space-to-ground infrared camouflage with radiative heat dissipation

Figure | 2 The multilayer camouflage device and its infrared camouflage performance. a, Photograph of the multilayer camouflage device. b, The absorptivity/emissivity spectra of the device. c, Infrared images of the device affixed to the satellite model in the MWIR, LWIR, H, K, and combined H&K bands.

Figure | 3 The simulated space environment.

Credit

Qin, B., Zhu, H., Zhu, R. et al.

New method of measuring gravity with 3D velocities of wide binary stars is developed and confirms modified gravity at low acceleration

Sejong University

image:

3D velocities versus sky-projected 2D velocities of a wide binary system. The new method uses the 3D velocities while all existing methods use the 2D velocities.

view moreCredit: Kyu-Hyun Chae

Wide binary stars with separation greater than about 2000 astronomical units are interesting natural laboratories that allow a direct probe of gravity at low acceleration weaker than about 1 nanometer per second squared. Astrophysicist Kyu-Hyun Chae at Sejong University (Seoul, South Korea) has developed a new method of measuring gravity with all three components of the velocities (3D velocities) of stars (Figure 1), as a major improvement over existing statistical methods relying on sky-projected 2D velocities. The new method based on the Bayes theorem derives directly the probability distribution of a gravity parameter (a parameter that measures the extent to which the data departs from standard gravitational dynamics) through the Markov Chain Monte Carlo simulation of the relative 3D velocity between the stars in a binary.

For the significance of the new method, Chae says, “The existing methods to infer gravity have the limitation that only the sky-projected velocities are used. Moreover, they have some limitations in accounting for the uncertainties of various factors including stellar masses to derive the probability distribution of a gravity parameter. The new method overcomes all these limitations. It is a sort of revolutionary and ultimate method for wide binaries whose motions can only be ‘snapshot-observed’ (that is, observed only at a specific phase of the orbital motion: because of the very long orbital periods of these binaries, a direct consequence of the low accelerations involved, one can only measure the positions and velocities of the stars at one moment, which is far less informative than having, ideally, data on a full orbit or at least a segment of it).” Chae adds, “However, the new method requires accurate and precise values of the third velocity component, that is, the line-of-sight (radial) velocity. In other words, only wide binaries with precisely measured radial velocities can be used.”

On the significance of the methodology, Xavier Hernandez, who initiated wide binary gravity tests in 2012, says, “The latest paper by Dr. K.-H. Chae on wide binaries presents a fully rigorous Bayesian approach which will surely become the standard in the field. Further, this latest paper presents also a proof of concept in going from 2-dimensional projected velocities to full 3D relative velocities between the two components of a wide binary. The level of accuracy reached from making full use of all available information is impressive.”

For the first application of the new method, Chae used about 300 wide binaries with relatively precise radial velocities selected from the European Space Agency’s Gaia data release 3. Although the first results are limited by the fact that Gaia’s reported radial velocities are not as precise as the sky-projected velocities, the derived probability distributions of gravity agree well with the recent results published by Chae and independently by Hernandez’s group as well. For wide binaries whose stars orbit each other with an internal acceleration greater than about 10 nanometers per second squared, the inferred gravity is precisely Newtonian, but for an internal acceleration lower than about 1 nanometer per second squared (or separation greater than about 2000 au), the inferred gravity is about 40 to 50 percent stronger than Newton. The significance of the deviation is 4.2sigma meaning that standard gravity is outside the 99.997 percent probability range. What is striking is that the deviation agrees with the generic prediction of modified gravity theories under the theoretical framework called modified Newtonian dynamics (MOND, sometimes referred to as Milgromian dynamics), introduced about 40 years ago by Mordehai (Moti) Milgrom.

On the first results based on the new method, Chae says, “It is encouraging that a direct inference of the probability distribution of gravity can be obtained for wide binaries that are bound by extremely weak internal gravity. This methodology may play a decisive role in the coming years in measuring gravity at low acceleration. It is nice that the first results agree well with the results for the past 2 years obtained by Hernandez’s group and myself with the existing methods.”

Pavel Kroupa, professor at the University of Bonn in Germany, says, “This is an impressive study of gravitation using very wide binaries as probes taken to a new level of accuracy and clarity by Prof. Dr. Kyu-Hyun Chae. This work greatly advances this topic, and the data, which will be improving over time, are already showing an increasingly significant deviation from Newtonian gravitation with an impressive consistency with the expectations from Milgromian gravitation. This has a major fundamentally important impact on theoretical physics and cosmology.”

Milgrom expresses his thoughts on the general significance of the wide binary results. “This new result by Prof. Chae strengthens in important ways earlier findings by him and others. They demonstrate a departure from the predictions of Newtonian dynamics in low-acceleration binary stars in our Galaxy. Such a departure from standard dynamics would be existing in itself. But it is even more exciting because it enters and appears in the same way as the departure from Newtonian dynamics appears in galaxies. It appears in the analysis only at or below a certain acceleration scale that is found to agree with the fundamental acceleration of MOND, and the magnitude of the anomaly they find is also consistent with the generic predictions of existing MOND theories. In galaxies, the observed (and MOND-predicted) anomaly is much larger, and is established very robustly, but much of the community support the view that it is due to the presence of dark matter; so, to them the galactic anomalies do not bespeak a conflict with standard dynamics. But, an anomaly as found by Prof. Chae, while more modest, cannot be accounted for by dark matter, and thus would indeed necessarily spell a breakdown of standard dynamics.”

Chae and his collaborators including Dongwook Lim and Young-Wook Lee at Yonsei University (Seoul, South Korea) and Byeong-Cheol Lee at Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute (Daejeon, South Korea) are now obtaining precise radial velocities from their new measurements using observation facilities such as GEMINI North Observatory (with the instrument MAROON-X) and Las Cumbres Observatory, and from archival data outside Gaia as well. Hernandez and his collaborators are carrying out the speckle photometry of target wide binaries to identify any systems with a hidden third star. Hernandez comments on this point, “This methodology requires using pure binaries that are free of any hidden companion stars. This highlights the relevance of upcoming results from dedicated ground-based follow-up studies which will unambiguously rule out dubious systems containing hidden third components and hence permit to reach the full potential of the new method.” When all these observation results are combined, decisive results on the low-acceleration anomaly are expected.

On the near future prospect Chae says, “With new data on radial velocities, most of which have already been obtained, and results from speckle photometric observations, the Bayesian inference is expected to measure gravity sufficiently precisely, not only to distinguish between Newton and MOND well above 5sigma, but also to narrow theoretical possibilities of gravitational dynamics. I expect exciting opportunities for theoretical physics with new results in the coming years.”

Caption

The inferred probability distribution (indicated by the thick blue-dotted magenta curve) of a gravity parameter (a measure of departure from standard gravity) is compared to the Newton-Einstein standard gravity. The standard gravity is outside the 99.997 percent probability range. Thin blue curves indicate individual probability distributions for 111 wide binaries with accelerations lower than about 1 nanometer per second squared, from which the combined distribution is obtained.

Credit

Kyu-Hyun Chae

Reference:

“Low-Acceleration Gravitational Anomaly from Bayesian 3D Modeling of Wide Binary Orbits: Methodology and Results with Gaia Data Release 3” published in the Astrophysical Journal on 27 May 2025 https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/adce09

https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.09373 (preprint archive)

Journal

The Astrophysical Journal

Method of Research

Computational simulation/modeling

Subject of Research

Not applicable

Article Title

Low-Acceleration Gravitational Anomaly from Bayesian 3D Modeling of Wide Binary Orbits: Methodology and Results with Gaia Data Release 3

Article Publication Date

27-May-2025

No comments:

Post a Comment