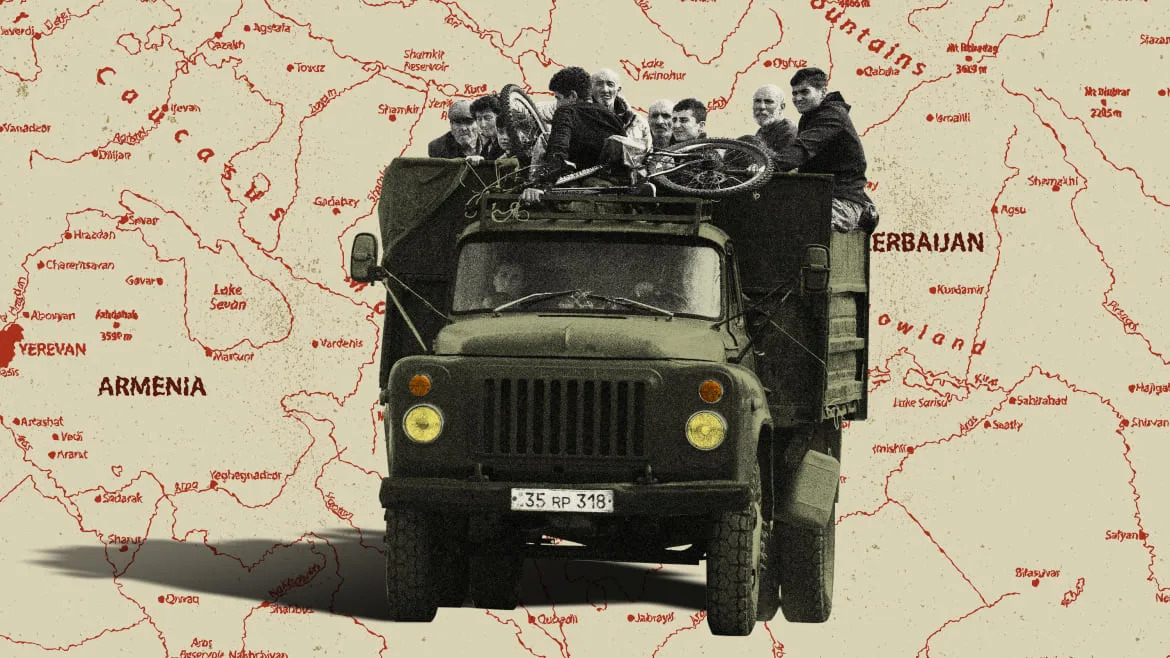

Huge queues of cars are leaving the territory in the direction of Armenia.

The ethnic Armenian inhabitants of the breakaway territory of Nagorno-Karabakh, which surrendered to Azerbaijan last Wednesday, are in mass flight to Armenia.

Social media carried photos of huge queues of cars leaving the territory in the direction of Armenia. Armenia's government said that almost 6,500 refugees had entered the country by 5pm local time on September 25.

Refugees are fleeing from areas occupied by Azerbaijani forces, as well as from areas that are poised to be occupied by them, in what risks becoming a humanitarian disaster.

“There are no words to describe [it],” one refugee told the Associated Press about their plight. “The village was heavily shelled. Almost no one is left in the village.”

In a statement the US government said it was “deeply concerned about reports on the humanitarian conditions in Nagorno-Karabakh and calls for unimpeded access for international humanitarian organisations and commercial traffic”.

Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan had advised the territory’s 120,000 residents last week not to leave but thousands have begun a mass exodus along the Lachin Corridor to Armenia rather than risk living under Azerbaijani rule. The road, which Azerbaijan has been blocking since December, is the territory’s only link with the outside world.

In an address on September 24, Pashinyan – who is facing huge domestic criticism and protests over the fall of Nagorno-Karabakh – said Azerbaijan was planning ethnic cleansing, and he admitted that a mass exodus now looked inevitable. Space for 40,000 people from Karabakh had been prepared in Armenia, Reuters reported.

"If proper conditions are not created for the Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh to live in their homes and there are no effective protection mechanisms against ethnic cleansing, the likelihood is rising that the Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh will see exile from their homeland as the only way to save their lives and identity," he said.

There were more demonstrations against Pashinyan on September 25 with more than 200 protesters detained.

Nagorno-Karabakh won self-rule in the early 1990s after the collapse of the Soviet Union but its declaration of independence has never been internationally recognised, even by Armenia. Its position was severely weakened in 2020 when Azerbaijan retook much of its lost territory.

Under the ceasefire Nagorno-Karabakh forces have begun handing in their arms after their surrender on Wednesday last week after a sudden 24-hour offensive by Azerbaijani forces. On the Nagorno-Karabakh side more than 200 people were killed and 400 were wounded in the Azerbaijani attack. Baku has not released casualty figures.

Ethnic Armenian residents of the territory lost in 2020 fled their homes and now many residents of the remaining rump statelet are expected to follow them.

"Ninety-nine point nine per cent prefer to leave our historic lands," David Babayan, an adviser to Nagorno-Karabakh’s’ president Samvel Shahramanyan told Reuters.

"The fate of our poor people will go down in history as a disgrace and a shame for the Armenian people and for the whole civilised world," Babayan said. "Those responsible for our fate will one day have to answer before God for their sins."

Nagorno-Karabakh leaders have said that all those wanting to leave the territory would be escorted to Armenia by Russian peacekeepers. Several thousand of those displaced by the recent fighting are already camped at the main airport, the base for the peacekeepers.

Talks on guarantees for the residents are continuing between Azerbaijani officials and representatives of the Nagorno-Karabakh government. Baku has pledged to respect the rights of the inhabitants of its breakaway region. Azerbaijan dictator Ilham Aliyev has said that the region would be turned into a "paradise". Baku has also begun to allow humanitarian aid to enter the territory, after blocking shipments for nine months.

However, these statements are widely dismissed because of Azerbaijan’s previous behaviour and its repression of dissent at home.

There is widespread fear that Azerbaijani forces will expel ethnic Armenians and will make reprisals against those who took part in the fighting over the past three decades, and those who led them. In recent weeks some ethnic Armenians who travelled through the Azerbaijani checkpoint on the Lachin Corridor have been arrested.

Hikmet Hajiyev, an adviser to Aliyev, told the Financial Times that Baku plans to fully absorb and integrate Nagorno-Karabakh, giving it no special autonomous status within Azerbaijan. He also said Baku was planning an “amnesty” for all Nagorno-Karabakh residents who served in separatist forces or with the Armenian army but that would not extend to “criminals, who have . . . used crimes against humanity and war crimes against Azerbaijani civilians. That is a separate story.”

Nagorno-Karabakh's 120,000 Armenians will leave for Armenia, leadership says

Sky News

Updated Sun, September 24, 2023

Almost all the 120,000 Armenians living in war-torn Nagorno-Karabakh will leave for Armenia, the region's de-facto leadership has said, after Azerbaijan regained control of the breakaway region.

The Armenians of Karabakh were forced to declare a ceasefire on Wednesday as Azeri forces reclaimed the territory following a 24-hour offensive.

The US and EU have expressed "deep concerns" for the Armenians in Karabakh, which is recognised internationally as part of Azerbaijan but had been under Armenian control since the fall of the Soviet Union.

Armenians say they fear repression and ethnic cleansing - allegations strongly denied by Azerbaijan.

David Babayan, an adviser to Samvel Shahramanyan, the president of the self-styled Republic of Artsakh, which is the Armenian name for the region, has warned of a mass exodus and says his people will not be part of Azerbaijan.

"Our people do not want to live as part of Azerbaijan, 99.9% prefer to leave our historic lands," he said. "The fate of our poor people will go down in history as a disgrace and a shame for the Armenian people and for the whole civilised world."

He said it was unclear when the Armenians would move down the Lachin corridor, which links the territory to Armenia, where Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan has faced calls to resign for failing to save Karabakh.

Meanwhile, long-awaited aid has arrived in the region following a nine-month blockade imposed by Azerbaijan, which dwindled the Armenians' food, fuel and medical supplies.

Azerbaijan has repeatedly said no harm will come to civilians - though reports suggest some may have died and residential buildings were damaged during the latest attack.

The country's ambassador to the UK, Elin Suleymanov, rejected claims his country would "ethnically cleanse" the region.

He told Sky News: "That is completely untrue. First, you don't offer food and aid to people you are planning to ethnically cleanse.

"Second, it was Armenia that committed ethnic cleansing in the 1990s. The reason there are only Armenians living in the region today is because the Armenians ethnically cleansed everyone else. It was a diverse region before the 1990s.

"We don't want to do what they did to us, we want to integrate that community into the diverse fabric of Azerbaijani society."

Asked if there could be peace, he said: "Of course there can be peace, there was peace in Europe after the Second World War, people nuked each other and now they are still friends."

The military offensive exacerbated problems for the population there, with many said to be sleeping outdoors and unable to get in touch with family and friends in rural areas.

The potential exodus from Karabakh marks another twist in the region's tumultuous and bloody history, with both Armenians and Azerbaijanis suffering greatly over the years.

Read more:

Azerbaijan claims full control of Nagorno-Karabakh

Protests in Armenia after dozens killed in Azerbaijan military offensive

Hundreds of thousands of Azerbaijanis were displaced following the first war between 1988-1994, which saw Armenian forces take control of the region and occupy surrounding areas.

The fate of the conflict's latest displaced people remains unclear, but Mr Pashinyan said in an address to the nation on Sunday that Armenia is ready to accept all compatriots from Karabakh.

Reuters

Updated Sun, September 24, 2023

MOSCOW, Sept 24 (Reuters) - Armenia's Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan said on Sunday the likelihood was rising that ethnic Armenians would flee the breakaway region of Nagorno-Karabakh and blamed Russia for failing to ensure Armenian security.

If 120,000 people go down the Lachin corridor to Armenia, the small South Caucasian country could face both a humanitarian and political crisis.

"If proper conditions are not created for the Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh to live in their homes and there are no effective protection mechanisms against ethnic cleansing, the likelihood is rising that the Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh will see exile from their homeland as the only way to save their lives and identity," Pashinyan said in address to the nation.

"Responsibility for such a development of events will fall entirely on Azerbaijan, which adopted a policy of ethnic cleansing, and on the Russian peacekeeping contingent in Nagorno-Karabakh," he said, according to a government transcript.

He added that the Armenian-Russian strategic partnership was "not enough to ensure the external security of Armenia".

Last week, Azerbaijan scored a victory over ethnic Armenians who have controlled the Karabakh region since the dissolution of the Soviet Union. An adviser to the leader of the Karabakh Armenians told Reuters earlier on Sunday that the population would leave because they feel unsafe under Azerbaijani rule.

Russia had acted as guarantor for a peace deal that ended a 44-day war in Karabakh three years ago, and many Armenians blame Moscow for failing to protect the region.

Russian officials say Pashinyan is to blame for his own mishandling of the crisis, and have repeatedly said that Armenia, which borders Turkey, Iran, Azerbaijan and Georgia, has few other friends in the region.

"The government will accept our brothers and sisters from Nagorno-Karabakh with full care," Pashinyan said.

Pashinyan has warned that some unidentified forces were seeking to stoke a coup against him and has accused Russian media of engaging in an information war against him.

"Some of our partners are increasingly making efforts to expose our security vulnerabilities, putting at risk not only our external, but also internal security and stability, while violating all norms of etiquette and correctness in diplomatic and interstate relations, including obligations assumed under treaties," Pashinyan said in his Sunday address.

"In this context, it is necessary to transform, complement and enrich the external and internal security instruments of the Republic of Armenia," he said.

Fleeing bombs and death, Karabakh Armenians recount visceral fear and hunger

Refugees from Nagorno-Karabakh arrive at Armenian checkpoint in Kornidzor

By Felix Light

Sun, September 24, 2023

GORIS, Armenia (Reuters) - After the village was bombed so hard there was no way to bury the truckloads of dead, he fled with his family and stuffed whatever possessions could be salvaged into two vans.

Petya Grigoryan is one of the first ethnic Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh to make it to Armenia after a lightning 24-hour Azerbaijani military operation defeated the Karabakh Armenian forces.

The ethnic Armenians of Karabakh, internationally recognised as part of Azerbaijan, say they will not live as part of Azerbaijan and that almost all of the 120,000 Armenians there will leave for Armenia.

So far several hundred have reached Armenia.

Grigoryan, a 69-year-old driver, said his Kochoghot village in what the Armenians know as the Martakert district of Karabakh was pummelled by Azerbaijan armed forces. There were two KAMAZ-truckloads full of civilian dead in the village, he said.

"There was nowhere to bury them," Grigoryan told Reuters after making his way down the Lachin corridor and across the border into Armenia, where Reuters interviewed him and other refugees in the border town of Goris.

"We took what we could and left. We don’t know where we’re going. We have nowhere to go," he said.

Of the 500 villagers, he said 40 had got out.

Reuters was unable to independently verify his account but it chimed with the outline given by other ethnic Armenians fleeing Karabakh, which Azerbaijan says will be turned into a "paradise" and fully integrated.

Azerbaijan said it launched the operation against Karabakh forces after attacks on its own citizens. President Ilham Aliyev said his army had only targeted Karabakh fighters and that civilians had been protected.

STRICT ORDER

"Before the operation, I once again gave a strict order to all our military units that the Armenian population living in the Karabakh region should not be affected by the anti-terrorist measures and that the civilian population be protected," he said in an address to the nation on Sept. 20.

"Civilians felt protected entirely thanks to the professionalism of our armed forces," he said.

Grigoryan and thousands of other Armenians made their way to the airport near the Karabakh capital, known as Stepanakert by Armenians and Khankendi by Azerbaijan, where some Russian peacekeepers are based.

"It was scary there," he said. Thousands slept on the ground without food and little water. "There was nothing to eat or drink; three days without food," he said.

Nairy, a builder from Leninakan, Armenia, said he had been trapped in Karabakh since December by the blockade. Then the Azerbaijan military shelled the Shosh village where he was staying.

"The kids were injured. We sat in the basements until the peacekeepers came in and took the people out," he said.

He too had made his way to the airport.

"We are extremely grateful to the lads for sharing their rations with the kids," he said. "The Russian peacekeepers went hungry to give the kids their rations."

At the airport, he said, there were thousands sleeping outside.

(Writing by Guy Faulconbridge; Editing by David Holmes)

UNITED NATIONS, Sept 23 (Reuters) - Russia's Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov said in a speech at the U.N. General Assembly on Saturday that time was ripe for trust-building measures between Armenia and Azerbaijan in Nagorno-Karabakh, and that Moscow's troops would help that.

Lavrov accused the West of trying to force themselves as mediators between the two countries, which he said was not needed.

"Yerevan and Baku actually did settle the situation," Lavrov said. "Time has come for mutual trust-building. There are Russian troops who will certainly help this," he said via translation.

Russia has peace-keeping missions in Nagorno-Karabakh, a separatist Armenian enclave inside Azerbaijan where Baku launched an offensive this week.

The ethnic Armenian leadership of breakaway Nagorno-Karabakh said on Saturday that the terms of their ceasefire with Azerbaijan were being implemented, with work proceeding on the delivery of humanitarian aid and evacuation of the wounded.

The fall of Nagorno-Karabakh

In a sense, all of this was expected. Nagorno-Karabakh and its ally, Armenia, had suffered a devastating defeat in the 2020 war.

After 32 years, the de facto independence of the Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh is reaching its end.

The tense and often-violated ceasefire that had governed the region since the end of the 2020 Second Karabakh War was overwhelmingly violated by Azerbaijan around 1pm local time on Tuesday. Azerbaijani military units, which had been gathering near the line of contact in Nagorno-Karabakh and on the borders of Armenia for weeks, launched a massive assault across all areas of the Nagorno-Karabakh frontline.

Artillery, precision missile strikes and airstrikes struck the beleaguered units of the Artsakh Defence Army, as the breakaway region’s military forces are known, while Azerbaijani infantry launched an offensive on the ground.

24 hours later, it was all over. Weakened by nine months of siege and starvation, without any supply lines to the outside world and hopelessly outmatched by Azerbaijan’s modern military, the president of the Republic of Artsakh, Samvel Shahramanyan, announced that his government had accepted the demands of Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev. The Artsakh Defence Army would be dissolved, its weapons would be handed over, and the region would, finally and definitively, come under Azerbaijani control.

In a sense, all of this was expected. Nagorno-Karabakh and its ally, Armenia, had suffered a devastating defeat in the 2020 war. Much of Nagorno-Karabakh had been captured – around 75% of the lands held by Karabakh Armenians before 2020 were conquered by Azerbaijan or ceded to them in the ceasefire agreement. The Armenian army, reeling from its losses, had been forced out of the conflict, left struggling to repel even the Azerbaijani incursions into Armenia itself.

The nine months of Azerbaijani blockade that began in December 2022 had been met with indifference from the international community, with ‘urges’ and ‘calls’ for Azerbaijan to reopen the Lachin Corridor – Nagorno-Karabakh’s single lifeline to the outside world – but no consequences when Azerbaijan refused to do so, ignoring even the International Court of Justice ruling on the matter.

The Russian peacekeeping mission, entrusted with ensuring that road remained open and active, similarly demurred from any real attempts to unblock it. Aliyev clearly read these signals – that there would be no consequences for violating yet another tenet of the 2020 ceasefire – and sent his army in for the kill.

Massive casualties

At the time of writing, so much is still unclear. The 24-hour war involved massive casualties: Nagorno-Karabakh’s authorities have confirmed over 200 dead and 400 wounded from their side, a number that is sure to rise as more bodies are found, while Azerbaijani social media reports place the number of Azerbaijan casualties at over 150.

What exactly happens next is anyone’s guess, including the people of Nagorno-Karabakh themselves. In the wake of the Azerbaijani assault and subsequent capture of numerous villages and key roads, tens of thousands of the region’s 120,000 inhabitants have been displaced. Stepanakert is overrun, with every public building hosting dozens of families; the city’s airport, the site of the main Russian peacekeeping base, is an even more dire site, with thousands of civilians now encamped there in the open air, having fled from the Azerbaijani soldiers who captured their villages.

Other areas are entirely isolated: the towns of Martuni and Martakert, Nagorno-Karabakh’s second- and third-largest settlements, are surrounded by Azerbaijani forces, their populations unable to escape and with little known about their condition.

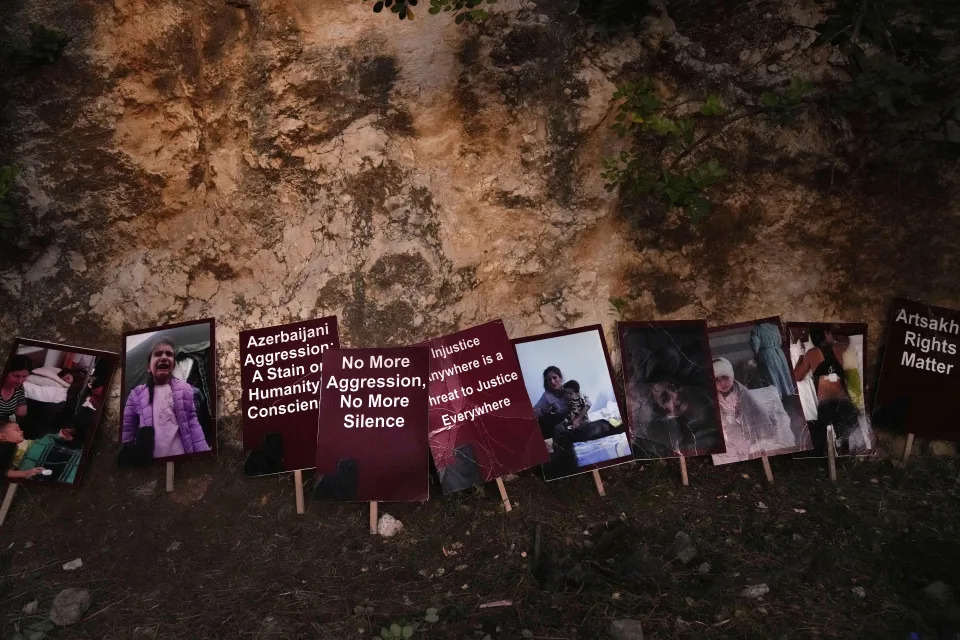

In this near-total information blackout, with no independent media access and limited internet connectivity, rumors of Azerbaijani atrocities have spread. One woman claimed that Azerbaijani troops had beheaded her three young children in front of her; another said that the same had happened to a Karabakh Armenian soldier. A woman named Sofik, from the Karabakh village of Sarnaghbyur, described in video testimony how Azerbaijani artillery bombardment of her village had killed at least five children and wounded 13 more.

There is little verification or ability to confirm these claims, but there is ample precedent for them: Azerbaijani troops have previously filmed themselves beheading elderly Karabakh Armenian civilians, have executed groups of POWs, and indiscriminately bombarded Karabakh settlements. In the coming days, videos of atrocities committed over the past few days are likely to come to light.

The ultimate fate of the population of Nagorno-Karabakh is similarly unclear. While Azerbaijani officials have said that civilians will be allowed to stay there unharmed, few, if any, of the locals believe them.

Armenian Prime Nikol Pashinyan stated in a speech on Thursday that a mass evacuation was “not plan A nor plan B,” and that he hoped the Karabakh Armenians would still be able to live a “safe and dignified” life there, but that Armenia was ready and able to accept 40,000 families if the need arose.

More despair than revolution

The view of Nagorno-Karabakh’s residents is a sharply different one. Ashot Gabrielyan, a local teacher who has documented life in Nagorno-Karabakh under the blockade, summed up the local community’s views in an Instagram post on Friday. “We, the people in Artsakh, need a humanitarian corridor to leave [to Armenia],” he wrote. “We are not ready to live with a country [Azerbaijan] which starved us, then killed us. We NEED to leave.”

The catastrophic situation has understandably led to political unrest in Armenia itself. On Tuesday night, as the Azerbaijani offensive into Nagorno-Karabakh was still going strong, thousands gathered in Yerevan’s Republic Square, a common spot for demonstrations in the capital. The clashes reached a rare level of violence, with police deploying stun grenades against the crowd at one point; 16 policemen and 18 civilians were wounded in the event.

But the mood was more despair than revolution. While many of those in attendance demanded the resignation of the government, few had any suggestions for what should be done differently.

“Nikol [Pashinyan] led us to this horrible situation, this catastrophe,” said Tigran, one of those in attendance. “He must resign.” Another attendee, Daniella, a 20-year old student from Nagorno-Karabakh, had a different take. “I don’t know what [the government] can even do [about this],” she said. “My family are still there [in Karabakh] and I’m very worried for them, but I don’t know that violence here [in Yerevan] will help anything,” she said.

The public paralysation is exacerbated by Russia, which has come out staunchly against the Armenian government and sought to pin the entire blame for the present tragedy in Nagorno-Karabakh on Pashinyan. A series of Kremlin media guidelines for Russian state media was leaked to the Russian opposition outlet Meduza, in which Russian government publications are instructed to blame the Azerbaijani assault on “Armenia and its Western partners”.

Mass public outrage at Russia and its absent peacekeepers in both Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh has been fanned further by posts by top Russian propagandists such as Margarita Simonyan and Vladimir Solovyov, who shared identical Telegram posts suggesting that Armenians should overthrow the Pashinyan government.

Armenian journalist Samson Martirosyan summed up the mood succinctly in a Twitter post. “Most people in Armenia don’t know what to do, caught between Pashinyan and [the] opposition. By going to protests, you would stir up chaos, which serves Russia and Azerbaijan. Not going would mean silently agreeing with Pashinyan’s disastrous policies,” Martirosyan wrote.

Meanwhile, the 120,000 inhabitants of Nagorno-Karabakh await the outcome of the surrender negotiations currently taking place between their leadership and that of Azerbaijan in the Azerbaijani city of Yevlakh.

There are few reasons for optimism: Nagorno-Karabakh presidential advisor David Babayan said on Friday that there were “no concrete results” from Baku on either security guarantees for the population of Karabakh or regarding amnesty for its soldiers and leaders, all of whom Azerbaijan regards as criminals and terrorists.

The Azerbaijani army currently sits at the entrances to Stepanakert, poised to enter. It is difficult to imagine the scenes that will result when that happens.

The Western reaction to Azerbaijan’s attack on Nagorno-Karabakh this week has been muted by its growing dependence on Azeri gas supplies.

Azerbaijan launched a so-called anti-terrorist operation in the enclave on September 19, shelling cities and towns that rapidly led to Nagorno-Karabakh’s surrender within 24 hours on September 20.

Thanks to the war in Ukraine, the EU has turned to Baku to replace the lost Russian gas deliveries. European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen travelled to Baku to sign a 10bn cubic metre gas supply deal last year as the EU scrambled to find new sources of gas.

“The European Union has therefore decided to diversify away from Russia and to turn towards more reliable, trustworthy partners. And I am glad to count Azerbaijan among them,” von der Leyen said in a speech to President Ilham Aliyev during her visit to Baku. “You are indeed a crucial energy partner for us and you have always been reliable.”

IEA chief Fatih Birol said at the time that new supplies of Azerbaijan still fall far short of being able to meet European demand for gas in the long term.

“It is categorically not enough to just rely on gas from non-Russian sources – these supplies are simply not available in the volumes required to substitute for missing deliveries from Russia,” Birol wrote in an article published by the IEA. “This will be the case even if gas supplies from Norway and Azerbaijan flow at maximum capacity.”

The gas deal doubled the supply of gas from Azerbaijan to the EU and committed to an expansion of the Southern Gas Corridor (SGC) to deliver more gas in the future.

“This is already a very important supply route for the European Union, delivering currently more than 8 bcm of gas per year,” von der Leyen said in Baku. “And we will expand its capacity to 20 bcm in a few years. From [2023] on, we should already reach 12 bcm. This will help compensate for cuts in supplies of Russian gas and contribute significantly to Europe's security of supply.”

Azerbaijan’s oil and gas export pipeline routes to the West

Leyen’s deal and personal meeting with President of Azerbaijan Ilham Aliyev was heavily criticised by NGOs for ignoring Azerbaijan’s widespread human rights abuses and brutal authoritarian control of the country.

The attack on Nagorno-Karabakh, which technically belongs to Azerbaijan, but is almost entirely populated by Armenians, has also brought down international criticism, as it appears that Baku is attempting to retake control of the enclave, force the residents out and replace them with Azeris.

Europe gets around 3% of its gas from Azerbaijan. However, as Baku has been piping more gas west to the EU, it has also been importing more gas from Russia in the east, as its domestic gas production is insufficient both to meet domestic demand and its export commitments to the EU. The Azeri gas deal is in fact a backdoor route for Russian to continue its gas exports to Europe, in addition to the ongoing exports via Ukraine and Turkey.

Aliev has been able to take advantage of Armenia’s relative isolation to bring about the attack and recapture of Nagorno-Karabakh. Russia is supposed to provide security in the region under the terms of the Collective Security Treaty Organisation (CSTO), but has been passive in the dispute, distracted by its own war in Ukraine.