Armenia accuses Azerbaijan of "ethnic cleansing" in Nagorno-Karabakh

Chris Livesay, Tucker Reals

Updated Fri, September 29, 2023

Armenia accuses Azerbaijan of "ethnic cleansing" in Nagorno-Karabakh

Armenia's Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan accused neighboring Azerbaijan on Thursday of "ethnic cleansing" as tens of thousands of people fled the Azerbaijani region of Nagorno-Karabakh into Armenia. Pashinyan predicted that all ethnic Armenians would flee the region in "the coming days" amid an ongoing Azerbaijani military operation there.

"Our analysis shows that in the coming days there will be no Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh," Pashinyan told his cabinet members on Thursday, according to the French news agency AFP. "This is an act of ethnic cleansing of which we were warning the international community for a long time."

Nagorno-Karabakh is internationally recognized as part of Azerbaijan, but it has been populated and run by ethnic Armenian separatists for several decades. About a week ago, Azerbaijan launched a lightning military offensive to bring the breakaway region — home to fewer than 150,000 people before the exodus began — fully under its control.

Over the last week, amid what Azerbaijan calls "anti-terrorist" operations in Nagorno-Karabakh, tens of thousands of people have fled to Armenia. Armenian government spokeswoman Nazeli Baghdasaryan said in a statement that some "65,036 forcefully displaced persons" had crossed into Armenia from the region by Thursday morning, according to AFP.

Some of the ethnic Armenian residents have said they had only minutes to decide to pack up their things and abandon their homes to join the exodus down the only road into neighboring Armenia.

"We ran away to survive," an elderly woman holding her granddaughter told the Reuters news agency. "It was horrible, children were hungry and crying."

Samantha Powers, the head of the U.S. government's primary aid agency, was in Armenia this week and announced that the U.S. government would provide $11.5 million worth of assistance.

"It is absolutely critical that independent monitors, as well as humanitarian organizations, get access to the people in Nagorno-Karabakh who still have dire needs," she said, adding that "there are injured civilians in Nagorno-Karabakh who need to be evacuated and it is absolutely essential that evacuation be facilitated by the government of Azerbaijan."

The conflict between the Armenian separatists in Nagorno-Karabakh and Azerbaijan had simmered for years, but after the recent invasion was launched, the separatists agreed to lay down their arms, leaving the future of their region and their people shrouded in uncertainty.

The fall of an enclave in Azerbaijan stuns the Armenian diaspora, extinguishing a dream

BASSEM MROUE

Updated Fri, September 29, 2023

Lebanese Armenians clash with police outside the Azerbaijani embassy in Beirut, Lebanon, Thursday, Sept. 28, 2023. The swift fall of the Armenian-majority enclave of Nagorno-Karabakh to Azerbaijani troops and exodus of much of its population has stunned the large Armenian diaspora around the world. Hundreds of Lebanese Armenians on Thursday protested outside the Azerbajani Embassy in Beirut. They waved flags of Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh and burned pictures of the Azerbaijani and Turkish presidents. Riot police lobbed tear gas when they threw firecrackers at the embassy.

(AP Photo/Hussein Malla, File)

BEIRUT (AP) — The swift fall of the Armenian-majority enclave of Nagorno-Karabakh to Azerbaijani troops and the exodus of much of its population has stunned the large Armenian diaspora around the world. Traumatized by a widely acknowledged genocide a century ago, they fear the erasure of what they consider a central and beloved part of their historic homeland.

The separatist ethnic Armenian government in Nagorno-Karabakh on Thursday announced that it was dissolving and that the unrecognized republic will cease to exist by year’s end -– a seeming death knell for its 30-year de facto independence.

Azerbaijan, which routed the region’s Armenian forces in a lightning offensive last week, has pledged to respect the rights of the territory’s Armenian community. Tens of thousands of people — more than 70% of the region's population — had fled to Armenia by Friday morning, and the influx continues, according to Armenian officials.

Many in Armenia and the diaspora fear a centuries-long community in the territory they call Artsakh will disappear.

Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan has termed it “a direct act of an ethnic cleansing.” Azerbaijan’s Foreign Ministry strongly rejected the accusation, saying the departures are a "personal and individual decision and has nothing to do with forced relocation.”

Armenians abroad also accuse European countries, Russia and the United States -– and the government of Armenia itself -– of failing to protect the population during months of a blockade of the territory by Azerbaijan’s military and a swift offensive last week that defeated separatist forces.

Armenians say the loss is a historic blow. Outside the modern country of Armenia itself, the mountainous land was one of the only surviving parts of a heartland that centuries ago stretched across what is now eastern Turkey, into the Caucasus region and western Iran.

Many in the diaspora had pinned dreams on it gaining independence or being joined to Armenia.

Nagorno-Karabakh was “a page of hope in Armenian history,” said Narod Seroujian, a Lebanese-Armenian university instructor in Beirut.

“It showed us that there is hope to gain back a land that is rightfully ours. … For the diaspora, Nagorno-Karabakh was already part of Armenia.”

Hundreds of Lebanese Armenians on Thursday protested outside the Azerbajani Embassy in Beirut. They waved flags of Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh and burned pictures of the Azerbaijani and Turkish presidents. Riot police lobbed tear gas when they threw firecrackers at the embassy.

Ethnic Armenians have communities around Europe and the Middle East and in the United States. Lebanon is home to one of the largest, with an estimated 120,000 of Armenian origin, 4% of the population.

Most are descendants of those who fled the 1915 campaign by Ottoman Turks in which some 1.5 million Armenians died in massacres, deportations and forced marches. The atrocities, which emptied many ethnic areas in eastern Turkey, are widely viewed by historians as genocide. Turkey rejects the description of genocide, saying the toll has been inflated and that those killed were victims of civil war and unrest during World War I.

In Bourj Hammoud, the main Armenian district in Beirut, memories are still raw, with anti-Turkey graffiti common. The red-blue-and-orange Armenian flag flies from many buildings.

“This is the last migration for Armenians,” said Harout Bshidikian, 55, sitting in front of an Armenian flag in a Bourj Hamoud cafe. “There is no other place left for us to migrate from.”

Azerbaijan says it is reuniting its territory, pointing out that even Armenia’s prime minister recognized that Nagorno-Karabakh is part of Azerbaijan. Though its population has been predominantly ethnic Armenian Christians, Turkish Muslim Azeris also have communities and cultural ties to the territory, particularly the city of Shusha, famed as a cradle of Azerbaijani poetry.

Following the breakup of the Soviet Union, Nagorno-Karabakh came under control of ethnic Armenian forces backed by the Armenian military in separatist fighting that ended in 1994. Azerbaijan took parts of the area in a 2020 war. Now after this month’s defeat, separatist authorities surrendered their weapons and are holding talks with Azerbaijan on reintegration of the territory into Azerbaijan.

Thomas de Waal, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Europe think tank, said Nagorno-Karabakh had become “a kind of new cause” for an Armenian diaspora whose forebearers had suffered the genocide.

“It was a kind of new Armenian state, new Armenian land being born, which they projected lots of hopes on. Very unrealistic hopes, I would say,” he added, noting it encouraged Karabakh Armenians to hold out against Azerbaijan despite the lack of international recognition for their separatist government.

Armenians see the territory as a cradle of their culture, with monasteries dating back more than a millennium.

“Artsakh or Nagorno-Karabakh has been a land for Armenians for hundreds of years,” said Lebanese legislator Hagop Pakradounian, head of Lebanon’s largest Armenian group, the Armenian Revolutionary Federation. “The people of Artsakh are being subjected to a new genocide, the first genocide in the 21st century.”

The fall of Nagorno-Karabakh is not just a reminder of the genocide, “it’s reliving it,” said Diran Guiliguian, a Madrid-based activist who holds Armenian, Lebanese and French citizenship.

He said his grandmother used to tell him stories of how she fled in 1915. The genocide “is actually not a thing of the past. It’s not a thing that is a century old. It’s actually still the case,” he said.

Seroujian, the instructor in Beirut, said her great-grandparents were genocide survivors, and that stories of the atrocities and dispersal were talked about at home, school and in the community as she grew up, as was the cause of Nagorno-Karabakh.

She visited the territory several times, most recently in 2017. “We’ve grown with these ideas, whether they were romantic or not, of the country. We’ve grown to love it even when we didn’t see it,” she said. “I never thought about it as something separate” from Armenia the country.

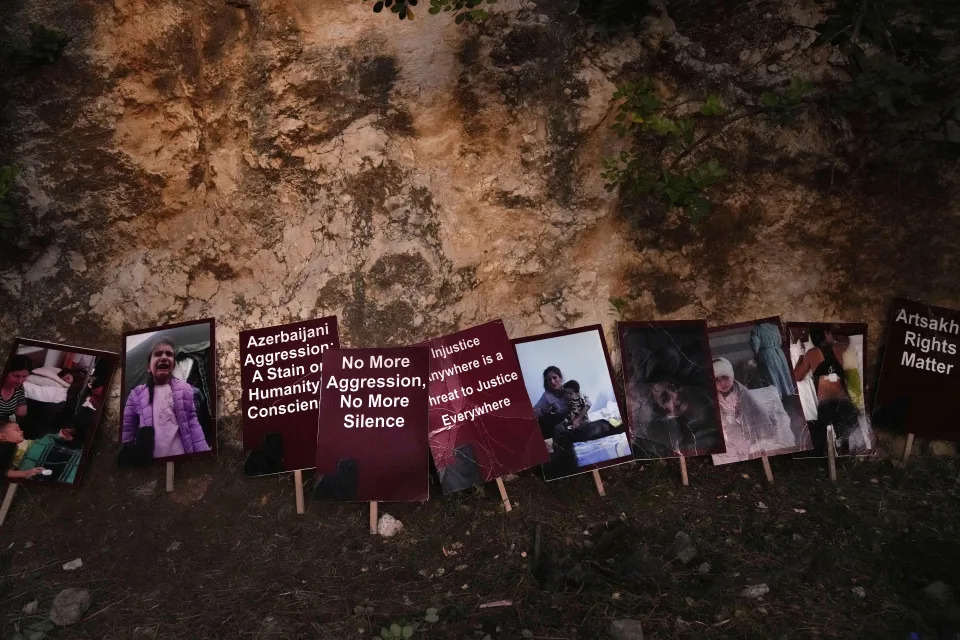

A diaspora group called Europeans for Artsakh plans a rally in Brussels next week in front of European Union buildings to denounce what they say are human rights abuses by Azerbaijan and to call for EU sanctions on Azerbaijani officials. The rally is timed ahead of an Oct. 5 summit of European leaders in Spain, where the Armenian prime minister and Azerbaijani president are scheduled to hold talks mediated by the French president, German chancellor and European Council president.

In the United States, the Armenian community in the Los Angeles area -– one of the world’s largest -– has staged protests to draw attention to the situation. On Sept. 19, they used a trailer truck to block a freeway for several hours, causing major traffic jams.

Kim Kardashian, perhaps the best-known Armenian-American, went on social media to urge President Joe Biden “to Stop Another Armenian Genocide.”

Several groups are collecting money for Karabakh Armenians fleeing their home. But Seroujian said many feel helpless.

“There are moments where personally, the family, or among friends we just feel hopeless,” she said. “And when we talk to each other we sort of lose our minds."

___

Associated Press writers Emma Burrows in London, Kareem Chehayeb and Fadi Tawil in Beirut, Angela Charlton in Paris and John Antczak in Los Angeles contributed.

Karabakh Armenians dissolve breakaway government in capitulation to Azerbaijan

Updated Thu, September 28, 2023

Refugees from Nagorno-Karabakh arrive in Kornidzor

By Felix Light

GORIS, Armenia (Reuters) -Ethnic Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh said on Thursday they were dissolving the breakaway statelet they had defended for three decades, where more than half the population has fled since Azerbaijan launched a lightning offensive last week.

In a statement, they said their self-declared Republic of Artsakh would "cease to exist" by Jan. 1, in what amounted to a formal capitulation to Azerbaijan.

For Azerbaijan and its president, Ilham Aliyev, the outcome is a triumphant restoration of sovereignty over an area that is internationally recognised as part of its territory but whose ethnic Armenian majority won de facto independence in a war in the 1990s.

For Armenians, it is a defeat and a national tragedy.

Some 70,500 people had crossed into Armenia by early Thursday afternoon, Russia's RIA news agency reported, out of an estimated population of 120,000.

"Analysis of the situation shows that in the coming days there will be no Armenians left in Nagorno-Karabakh," Interfax news agency quoted Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan as saying. "This is an act of ethnic cleansing."

Azerbaijan denies that accusation, saying it is not forcing people to leave and that it will peacefully reintegrate the Karabakh region and guarantee the civic rights of the ethnic Armenians.

Karabakh Armenians say they do not trust that promise, mindful of a long history of bloodshed between the two sides including two wars since the break-up of the Soviet Union. For days they have fled en masse down the snaking mountain road through Azerbaijan that connects Karabakh to Armenia.

Azerbaijan's ambassador to London, Elin Suleymanov, told Reuters in an interview that Baku did not want a mass exodus from Karabakh and was not encouraging people to leave.

He said Azerbaijan had not yet had a chance to prove what he said was its sincere commitment to provide secure and better living conditions for those ethnic Armenians who choose to stay.

The Kremlin said on Thursday it was closely monitoring the humanitarian situation in Karabakh and said Russian peacekeepers in the region were providing assistance to residents. It said Russian President Vladimir Putin had no plans to visit Armenia.

'TROUBLING REPORTS'

Western governments have also expressed alarm over the humanitarian crisis and demanded access for international observers to monitor Azerbaijan's treatment of the local population.

Samantha Power, head of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), said this week she had heard "very troubling reports of violence against civilians".

Azerbaijan said Aliyev had told her at a meeting on Wednesday that the rights of ethnic Armenians would be protected by law, like those of other minorities.

"The Azerbaijani president noted that the civilian population had not been harmed during the anti-terrorist measures, and only illegal Armenian armed formations and military facilities had been targeted," a statement said.

Aliyev's office said on Thursday he was visiting Jabrayil, a city on the southern edge of Karabakh that was destroyed by Armenian forces in the 1990s, which Azerbaijan recaptured in 2020 and is now rebuilding.

While saying he had no quarrel with ordinary Karabakh Armenians, Aliyev last week described their leaders as a "criminal junta" that would be brought to justice.

A former head of Karabakh's government, Ruben Vardanyan, was arrested on Wednesday as he tried to cross into Armenia. Azerbaijan's state security service said on Thursday he was being charged with financing terrorism and with illegally crossing the Azerbaijani border last year.

David Babayan, an adviser to the Karabakh leadership, said in a statement he was voluntarily giving himself up to the Azerbaijani authorities.

Mass displacements have been a feature of the Karabakh conflict since it broke out in the late 1980s as the Soviet Union headed towards collapse.

Between 1988 and 1994 about 500,000 Azerbaijanis from Karabakh and the areas around it were expelled from their homes, while the conflict prompted 350,000 Armenians to leave Azerbaijan and 186,000 Azerbaijanis to leave Armenia, according to "Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan Through Peace and War", a 2003 book by Caucasus scholar and analyst Thomas de Waal.

Many of the Armenians escaping this week in heavily laden cars, trucks, buses and even tractors said they were hungry and fearful.

"This is one of the darkest pages of Armenian history," said Father David, a 33-year-old Armenian priest who came to the border to provide spiritual support for those arriving. "The whole of Armenian history is full of hardships."

(Additional reporting by Nailia Bagirova and Anton Kolodyazhnyy; writing by Mark Trevelyan and Gareth Jones; Editing by Kevin Liffey, Alexandra Hudson)

Nagorno-Karabakh to dissolve, ending independence dream

AFP

Thu, September 28, 2023

Nagorno-Karabakh's decades-long, bloody dream of independence ended on Thursday with a formal decree declaring that the ethnic Armenian statelet in Azerbaijan "ceases to exist" at the end of the year.

The dramatic decree issued by the separatist region's leader came moments after it was announced that more than half of the ethnic Armenian population has fled in the wake of last week's assault by arch-rival Azerbaijan.

Baku's lightning offensive ended with a September 20 truce in the which the rebels pledged to disarm and enter "reintegration" talks.

Two rounds of talks were held as Azerbaijani forces methodically worked with Russian peacekeepers to collect separatist weapons silos and enter towns that had remained outside Baku's control since the sides first fought over the region in the 1990s.

Azerbaijani forces have now approached the edge of Stepanakert -- an emptying rebel stronghold where separatist leader Samvel Shakhramanyan issued his decree.

"Dissolve all state institutions and organisations under their departmental subordination by January 1, 2024, and the Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh (Artsakh) ceases to exist," said the decree.

"The population of Nagorno-Karabakh, including those located outside the republic, after the entry into force of this Decree, familiarise themselves with the conditions of reintegration presented by the Republic of Azerbaijan."

- 'Ethnic cleansing' -

The republic and its separatist dream have been effectively vanishing since Azerbaijan unlocked the only road leading to Armenia on Sunday.

Tens of thousands have since been piling their belonging on top of their cars and taking the winding mountain journey to Armenia every day.

Armenia said more than 65,000 had left by Thursday morning -- more than half of the region's estimated 120,000-strong population.

Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan said Thursday that "in the coming days" all ethnic-Armenians will have left the region, where ethnic Armenians have been living for centuries.

"This is an act of ethnic cleansing of which we were warning the international community (about for a long time."

Nagorno-Karabakh has been officially recognised as part of Azerbaijan since the Soviet Union's collapse in 1991.

No country -- not even Armenia -- recognised the statelet's independence claim.

But ethnic Armenian separatists have been running the region since winning a brutal war in the 1990s that claimed tens of thousands of lives.

The fighting was accompanied by allegations of massacres against civilians and gross violations of human rights that many in the region recall to this day.

But the bloody feud between the mostly Christian Armenian and predominantly Muslim Azerbaijan dates back to the years in the 1920s when the region was handed to Baku by the Soviets.

Baku clawed back large parts of the statelet and its surrounding areas in a six-week war in 2020 that significantly weakened rebel defences.

Azerbaijan has agreed to allow rebel fighters who lay down their arms to withdraw to Armenia.

But Baku added that it reserved the right to detain and prosecute suspects of "war crimes".

Azerbaijani border guards on Wednesday detained Ruben Vardanyan -- a reported billionaire who headed the Nagorno-Karabakh government from November 2022 until February.

Baku said on Thursday it had charged Vardanyan with "financing terrorism".

The region's former foreign minister David Babayan said he had also been added to Baku's "black list" and agreed to hand himself over to Azerbaijani authorities.

Why this week's mass exodus from embattled Nagorno-Karabakh reflects decades of animosity

JIM HEINTZ

Updated Thu, September 28, 2023

Armenia AzerbaijanEthnic Armenian elderly women from Nagorno-Karabakh rest after arriving in Armenia's Goris in Syunik region, Armenia, Thursday, Sept. 28, 2023. Armenian officials say over 66,000 people — more than half of the region's population of 120,000 — has already left for Armenia.

Exodus and ethnic cleansing? The sudden end of a decades long dream in the Caucasus

Matt Bradley and Natasha Lebedeva

Thu, September 28, 2023

Nagorno-Karabakh to dissolve after years-long war with Azerbaijan ends

After years of conflict, the war between Nagorno-Karabakh and Azerbaijan has finally ended. The contested region now falls under Azerbaijani control as tens of thousands of ethnic Armenians flee their homeland. NBC News’ Matt Bradley reports.

After more than half the population of an ethnic Armenian enclave fled their homes in a mountainous pocket of land south of Russia, the breakaway republic’s leaders said it would soon “cease to exist.”

In what amounted to a formal capitulation to Azerbaijan, which surrounds it, the Armenian leaders of Nagorno-Karabakh said the self-declared Republic of Artsakh would be dismantled by the end of the year.

This would end three decades of intermittent conflict in and around the enclave, break a 10-month blockade of the region in the South Caucasus that residents said had starved them into submission, and dash hopes of an independent state in territory claimed by Azerbaijan.

The dissolution of Nagorno-Karabakh as a breakaway state is a seminal point — a rare supernova among the constellation of ethnic conflicts left by the implosion of the then-Soviet Union in the early 1990s. The conflict’s abrupt halt reflects how the geopolitical reach of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has forced realignments far beyond that war.

In an official decree, the region’s separatist President Samvel Shakhramanyan said that residents of Nagorno-Karabakh must now “familiarize themselves with the conditions of reintegration” into Azerbaijan and make “an independent and individual decision about the possibility of staying (or returning) in Nagorno-Karabakh.”

The announcement came as around 70,000 of the enclave’s population of about 120,000 fled from the region, which sits within Azerbaijan’s borders, to neighboring Armenia, according to Armenia’s government, with more still arriving.

Many residents hauled what few personal belongings they could gather into packed cars, trucks, buses and tractors, some pockmarked with shrapnel after days of Azerbaijani attacks.

Armenia’s leadership has accused Azerbaijan of instigating a refugee crisis by launching a swift invasion this week. Azerbaijan has denied allegations of “ethnic cleansing,” saying it is not forcing people to leave, and would peacefully reintegrate the region and guarantee rights of ethnic Armenians.

Holding a wealth of monasteries, mosques and other religious sites, Nagorno-Karabakh is culturally significant for both Muslim Azeris and what was an overwhelming Christian Armenian population. Armenians in Azerbaijan have been victims of pogroms, while Azerbaijanis claim discrimination and violence at the hands of Armenians.

“Azerbaijan has won a comprehensive military victory and what we’re looking at now is the prospect of Nagorno-Karabakh without Armenians or with very few Armenians remaining,” said Thomas de Waal, a senior fellow with the London-based Carnegie Europe think tank. “So in that sense, Azerbaijan has won.”

For those fleeing, the despair of losing their homes was made worse by losing their homeland.

“Many of them are from villages which were taken by the Azerbaijani army, so they really lost their homes already,” said Astrig Agopian, a French Armenian journalist who has been reporting this week on the refugee crisis from Armenia’s border. “There is really this feeling that this time is different. It’s another war, but it’s a war that is definitely lost this time.”

Were that the case, it would bring to an end decades of violence in the region, which has been at the center of geopolitical interests between Eastern and Western nations for centuries.

The political dispute between Armenia and Azerbaijan over Nagorno-Karabakh began as the then-Soviet Union weakened in the late 1980s, and Armenians demanded that the majority-Armenian region be incorporated into the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic.

After the USSR collapsed in 1991, the conflict erupted into a full-scale war that persisted until a Russian-brokered peace deal in 1994. About 30,000 people were killed and more than a million people displaced.

“My husband died in the first war. He was 30, I was 26. Our children were 3 and 4 years old. It is the fourth war that I went through,” Narine Shakaryan, a grandmother of four, told the Reuters news agency after she arrived in Armenia. “My husband died back then, he was 30 in 1994. That’s the cursed life that we live.”

The fighting continued intermittently for several more decades, leaving an indelible mark on generations of Nagorno-Karabakh’s ethnic Armenian residents. A recent war in 2020 saw the more powerful Azerbaijan, backed by Turkey, reclaim much of the land surrounding the area, as well as part of the region itself.

Russia negotiated an end to that flare-up and even deployed peacekeepers to ensure security along the Lachin Corridor, the single mountain road that connected Armenia to Nagorno-Karabakh.

But the events of the past year show how Moscow, which has historically played the role of both peacekeeper and ally to Armenia — which shares its Christian roots and hosts a Russian military base — has adjusted its allegiances following its invasion of Ukraine and its conflicts with the West.

“The pivotal factor was that Azerbaijan was talking separately to the Russians, and had a joint agenda with the Russians, to pressure Armenia and also to keep the West out of the Caucasus,” de Waal said. “This is why when the Azerbaijani assault happened, Russian peacekeepers who could have actually stopped it stood down. And then Russia failed to condemn the attack.”

After its invasion of Ukraine left Russia isolated, Moscow may feel it has more to gain from cozying up to Azerbaijan than Armenia, particularly after the latter made a public display of cozying up to the West and provided humanitarian aid to Kyiv.

Earlier this month, the country conducted joint exercises with the U.S. military and the Armenian Parliament is set to vote next week on whether to accede to the International Criminal Court, which classifies Russian President Vladimir Putin as a war criminal — a move the Kremlin characterized Thursday as “extremely hostile.”

Inside Nagorno-Karabakh, Azerbaijan’s government has assured the region’s Armenian population that they will be treated humanely and afforded equal rights.

But after months of blockades and blistering fighting, few ethnic Armenians believe it and many feel they have no choice but to flee.

This article was originally published on NBCNews.com

Armenians in Russia return home to help Karabakh refugees

Felix Light

Wed, September 27, 2023

Refugees from Nagorno-Karabakh arrive in Kornidzor

KORNIDZOR, Armenia (Reuters) - When Azerbaijan overran the breakaway region of Nagorno-Karabakh, David Harapetyan drove 1,000 km (620 miles) from his home in the Russian city of Stavropol to this Armenian border village to help fleeing Karabakh Armenians.

The 36-year-old taxi driver on Wednesday was handing out food, water and cigarettes to refugees arriving in Armenia after spending 10 months under an Azerbaijani blockade that led to critical shortages in Karabakh.

"I came here from Stavropol when I saw what is happening here. I came to help my people however I can," said Harapetyan, who was born in this southern corner of Armenia but holds only Russian citizenship.

Russia is home to the world's largest Armenian diaspora. The United States and France also have large ethnic Armenian communities.

Armenia’s government said on Wednesday that more than 50,000 Karabakh refugees so far had crossed the border, out of a total estimated Karabakh Armenian population of 120,000.

The sudden influx has strained resources in Goris, the border town where Armenian authorities have booked out hotels for refugees with nowhere to go.

Harapetyan said he and a group of 10 Stavropol Armenians he had arrived with were helping new arrivals with accommodation.

"We arrived and even found houses where we can accommodate some people who have no home."

Among those helped by Harapetyan were 49 men, women and children who arrived crammed into Karen Martirosyan’s KAMAZ truck.

Martirosyan, 39, a soldier in Karabakh’s defeated army, had driven from the frontline village of Badara in his truck.

BREAKDOWNS

During the 77 km (48 mile) drive from Stepanakert, the capital of Karabakh, which took two days due to heavy traffic, he picked up stragglers whose truck had broken down.

"Their KAMAZ broke down on the road late at night," said Martirosyan, whose own overloaded truck was also towing a car carrying five more people who had run out of fuel.

"They were out in the open. So I took them with me and came here - 43 (people) in the back, and five more in the cabin."

As volunteers at the border gave out food and water to the 20 or so children on board, an old woman shouted from the truck that she blamed Armenian and Karabakh leaders, past and present, for the loss of her homeland.

"All of Karabakh has been taken hostage by Azerbaijan! That's it! It's all our president's fault! He did all of it, he is the one responsible!"

(Writing by Gareth Jones, Editing by William Maclean)

BEIRUT (AP) — The swift fall of the Armenian-majority enclave of Nagorno-Karabakh to Azerbaijani troops and the exodus of much of its population has stunned the large Armenian diaspora around the world. Traumatized by a widely acknowledged genocide a century ago, they fear the erasure of what they consider a central and beloved part of their historic homeland.

The separatist ethnic Armenian government in Nagorno-Karabakh on Thursday announced that it was dissolving and that the unrecognized republic will cease to exist by year’s end -– a seeming death knell for its 30-year de facto independence.

Azerbaijan, which routed the region’s Armenian forces in a lightning offensive last week, has pledged to respect the rights of the territory’s Armenian community. Tens of thousands of people — more than 70% of the region's population — had fled to Armenia by Friday morning, and the influx continues, according to Armenian officials.

Many in Armenia and the diaspora fear a centuries-long community in the territory they call Artsakh will disappear.

Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan has termed it “a direct act of an ethnic cleansing.” Azerbaijan’s Foreign Ministry strongly rejected the accusation, saying the departures are a "personal and individual decision and has nothing to do with forced relocation.”

Armenians abroad also accuse European countries, Russia and the United States -– and the government of Armenia itself -– of failing to protect the population during months of a blockade of the territory by Azerbaijan’s military and a swift offensive last week that defeated separatist forces.

Armenians say the loss is a historic blow. Outside the modern country of Armenia itself, the mountainous land was one of the only surviving parts of a heartland that centuries ago stretched across what is now eastern Turkey, into the Caucasus region and western Iran.

Many in the diaspora had pinned dreams on it gaining independence or being joined to Armenia.

Nagorno-Karabakh was “a page of hope in Armenian history,” said Narod Seroujian, a Lebanese-Armenian university instructor in Beirut.

“It showed us that there is hope to gain back a land that is rightfully ours. … For the diaspora, Nagorno-Karabakh was already part of Armenia.”

Hundreds of Lebanese Armenians on Thursday protested outside the Azerbajani Embassy in Beirut. They waved flags of Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh and burned pictures of the Azerbaijani and Turkish presidents. Riot police lobbed tear gas when they threw firecrackers at the embassy.

Ethnic Armenians have communities around Europe and the Middle East and in the United States. Lebanon is home to one of the largest, with an estimated 120,000 of Armenian origin, 4% of the population.

Most are descendants of those who fled the 1915 campaign by Ottoman Turks in which some 1.5 million Armenians died in massacres, deportations and forced marches. The atrocities, which emptied many ethnic areas in eastern Turkey, are widely viewed by historians as genocide. Turkey rejects the description of genocide, saying the toll has been inflated and that those killed were victims of civil war and unrest during World War I.

In Bourj Hammoud, the main Armenian district in Beirut, memories are still raw, with anti-Turkey graffiti common. The red-blue-and-orange Armenian flag flies from many buildings.

“This is the last migration for Armenians,” said Harout Bshidikian, 55, sitting in front of an Armenian flag in a Bourj Hamoud cafe. “There is no other place left for us to migrate from.”

Azerbaijan says it is reuniting its territory, pointing out that even Armenia’s prime minister recognized that Nagorno-Karabakh is part of Azerbaijan. Though its population has been predominantly ethnic Armenian Christians, Turkish Muslim Azeris also have communities and cultural ties to the territory, particularly the city of Shusha, famed as a cradle of Azerbaijani poetry.

Following the breakup of the Soviet Union, Nagorno-Karabakh came under control of ethnic Armenian forces backed by the Armenian military in separatist fighting that ended in 1994. Azerbaijan took parts of the area in a 2020 war. Now after this month’s defeat, separatist authorities surrendered their weapons and are holding talks with Azerbaijan on reintegration of the territory into Azerbaijan.

Thomas de Waal, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Europe think tank, said Nagorno-Karabakh had become “a kind of new cause” for an Armenian diaspora whose forebearers had suffered the genocide.

“It was a kind of new Armenian state, new Armenian land being born, which they projected lots of hopes on. Very unrealistic hopes, I would say,” he added, noting it encouraged Karabakh Armenians to hold out against Azerbaijan despite the lack of international recognition for their separatist government.

Armenians see the territory as a cradle of their culture, with monasteries dating back more than a millennium.

“Artsakh or Nagorno-Karabakh has been a land for Armenians for hundreds of years,” said Lebanese legislator Hagop Pakradounian, head of Lebanon’s largest Armenian group, the Armenian Revolutionary Federation. “The people of Artsakh are being subjected to a new genocide, the first genocide in the 21st century.”

The fall of Nagorno-Karabakh is not just a reminder of the genocide, “it’s reliving it,” said Diran Guiliguian, a Madrid-based activist who holds Armenian, Lebanese and French citizenship.

He said his grandmother used to tell him stories of how she fled in 1915. The genocide “is actually not a thing of the past. It’s not a thing that is a century old. It’s actually still the case,” he said.

Seroujian, the instructor in Beirut, said her great-grandparents were genocide survivors, and that stories of the atrocities and dispersal were talked about at home, school and in the community as she grew up, as was the cause of Nagorno-Karabakh.

She visited the territory several times, most recently in 2017. “We’ve grown with these ideas, whether they were romantic or not, of the country. We’ve grown to love it even when we didn’t see it,” she said. “I never thought about it as something separate” from Armenia the country.

A diaspora group called Europeans for Artsakh plans a rally in Brussels next week in front of European Union buildings to denounce what they say are human rights abuses by Azerbaijan and to call for EU sanctions on Azerbaijani officials. The rally is timed ahead of an Oct. 5 summit of European leaders in Spain, where the Armenian prime minister and Azerbaijani president are scheduled to hold talks mediated by the French president, German chancellor and European Council president.

In the United States, the Armenian community in the Los Angeles area -– one of the world’s largest -– has staged protests to draw attention to the situation. On Sept. 19, they used a trailer truck to block a freeway for several hours, causing major traffic jams.

Kim Kardashian, perhaps the best-known Armenian-American, went on social media to urge President Joe Biden “to Stop Another Armenian Genocide.”

Several groups are collecting money for Karabakh Armenians fleeing their home. But Seroujian said many feel helpless.

“There are moments where personally, the family, or among friends we just feel hopeless,” she said. “And when we talk to each other we sort of lose our minds."

___

Associated Press writers Emma Burrows in London, Kareem Chehayeb and Fadi Tawil in Beirut, Angela Charlton in Paris and John Antczak in Los Angeles contributed.

Karabakh Armenians dissolve breakaway government in capitulation to Azerbaijan

Updated Thu, September 28, 2023

Refugees from Nagorno-Karabakh arrive in Kornidzor

By Felix Light

GORIS, Armenia (Reuters) -Ethnic Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh said on Thursday they were dissolving the breakaway statelet they had defended for three decades, where more than half the population has fled since Azerbaijan launched a lightning offensive last week.

In a statement, they said their self-declared Republic of Artsakh would "cease to exist" by Jan. 1, in what amounted to a formal capitulation to Azerbaijan.

For Azerbaijan and its president, Ilham Aliyev, the outcome is a triumphant restoration of sovereignty over an area that is internationally recognised as part of its territory but whose ethnic Armenian majority won de facto independence in a war in the 1990s.

For Armenians, it is a defeat and a national tragedy.

Some 70,500 people had crossed into Armenia by early Thursday afternoon, Russia's RIA news agency reported, out of an estimated population of 120,000.

"Analysis of the situation shows that in the coming days there will be no Armenians left in Nagorno-Karabakh," Interfax news agency quoted Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan as saying. "This is an act of ethnic cleansing."

Azerbaijan denies that accusation, saying it is not forcing people to leave and that it will peacefully reintegrate the Karabakh region and guarantee the civic rights of the ethnic Armenians.

Karabakh Armenians say they do not trust that promise, mindful of a long history of bloodshed between the two sides including two wars since the break-up of the Soviet Union. For days they have fled en masse down the snaking mountain road through Azerbaijan that connects Karabakh to Armenia.

Azerbaijan's ambassador to London, Elin Suleymanov, told Reuters in an interview that Baku did not want a mass exodus from Karabakh and was not encouraging people to leave.

He said Azerbaijan had not yet had a chance to prove what he said was its sincere commitment to provide secure and better living conditions for those ethnic Armenians who choose to stay.

The Kremlin said on Thursday it was closely monitoring the humanitarian situation in Karabakh and said Russian peacekeepers in the region were providing assistance to residents. It said Russian President Vladimir Putin had no plans to visit Armenia.

'TROUBLING REPORTS'

Western governments have also expressed alarm over the humanitarian crisis and demanded access for international observers to monitor Azerbaijan's treatment of the local population.

Samantha Power, head of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), said this week she had heard "very troubling reports of violence against civilians".

Azerbaijan said Aliyev had told her at a meeting on Wednesday that the rights of ethnic Armenians would be protected by law, like those of other minorities.

"The Azerbaijani president noted that the civilian population had not been harmed during the anti-terrorist measures, and only illegal Armenian armed formations and military facilities had been targeted," a statement said.

Aliyev's office said on Thursday he was visiting Jabrayil, a city on the southern edge of Karabakh that was destroyed by Armenian forces in the 1990s, which Azerbaijan recaptured in 2020 and is now rebuilding.

While saying he had no quarrel with ordinary Karabakh Armenians, Aliyev last week described their leaders as a "criminal junta" that would be brought to justice.

A former head of Karabakh's government, Ruben Vardanyan, was arrested on Wednesday as he tried to cross into Armenia. Azerbaijan's state security service said on Thursday he was being charged with financing terrorism and with illegally crossing the Azerbaijani border last year.

David Babayan, an adviser to the Karabakh leadership, said in a statement he was voluntarily giving himself up to the Azerbaijani authorities.

Mass displacements have been a feature of the Karabakh conflict since it broke out in the late 1980s as the Soviet Union headed towards collapse.

Between 1988 and 1994 about 500,000 Azerbaijanis from Karabakh and the areas around it were expelled from their homes, while the conflict prompted 350,000 Armenians to leave Azerbaijan and 186,000 Azerbaijanis to leave Armenia, according to "Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan Through Peace and War", a 2003 book by Caucasus scholar and analyst Thomas de Waal.

Many of the Armenians escaping this week in heavily laden cars, trucks, buses and even tractors said they were hungry and fearful.

"This is one of the darkest pages of Armenian history," said Father David, a 33-year-old Armenian priest who came to the border to provide spiritual support for those arriving. "The whole of Armenian history is full of hardships."

(Additional reporting by Nailia Bagirova and Anton Kolodyazhnyy; writing by Mark Trevelyan and Gareth Jones; Editing by Kevin Liffey, Alexandra Hudson)

Nagorno-Karabakh to dissolve, ending independence dream

AFP

Thu, September 28, 2023

Nagorno-Karabakh's decades-long, bloody dream of independence ended on Thursday with a formal decree declaring that the ethnic Armenian statelet in Azerbaijan "ceases to exist" at the end of the year.

The dramatic decree issued by the separatist region's leader came moments after it was announced that more than half of the ethnic Armenian population has fled in the wake of last week's assault by arch-rival Azerbaijan.

Baku's lightning offensive ended with a September 20 truce in the which the rebels pledged to disarm and enter "reintegration" talks.

Two rounds of talks were held as Azerbaijani forces methodically worked with Russian peacekeepers to collect separatist weapons silos and enter towns that had remained outside Baku's control since the sides first fought over the region in the 1990s.

Azerbaijani forces have now approached the edge of Stepanakert -- an emptying rebel stronghold where separatist leader Samvel Shakhramanyan issued his decree.

"Dissolve all state institutions and organisations under their departmental subordination by January 1, 2024, and the Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh (Artsakh) ceases to exist," said the decree.

"The population of Nagorno-Karabakh, including those located outside the republic, after the entry into force of this Decree, familiarise themselves with the conditions of reintegration presented by the Republic of Azerbaijan."

- 'Ethnic cleansing' -

The republic and its separatist dream have been effectively vanishing since Azerbaijan unlocked the only road leading to Armenia on Sunday.

Tens of thousands have since been piling their belonging on top of their cars and taking the winding mountain journey to Armenia every day.

Armenia said more than 65,000 had left by Thursday morning -- more than half of the region's estimated 120,000-strong population.

Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan said Thursday that "in the coming days" all ethnic-Armenians will have left the region, where ethnic Armenians have been living for centuries.

"This is an act of ethnic cleansing of which we were warning the international community (about for a long time."

Nagorno-Karabakh has been officially recognised as part of Azerbaijan since the Soviet Union's collapse in 1991.

No country -- not even Armenia -- recognised the statelet's independence claim.

But ethnic Armenian separatists have been running the region since winning a brutal war in the 1990s that claimed tens of thousands of lives.

The fighting was accompanied by allegations of massacres against civilians and gross violations of human rights that many in the region recall to this day.

But the bloody feud between the mostly Christian Armenian and predominantly Muslim Azerbaijan dates back to the years in the 1920s when the region was handed to Baku by the Soviets.

Baku clawed back large parts of the statelet and its surrounding areas in a six-week war in 2020 that significantly weakened rebel defences.

Azerbaijan has agreed to allow rebel fighters who lay down their arms to withdraw to Armenia.

But Baku added that it reserved the right to detain and prosecute suspects of "war crimes".

Azerbaijani border guards on Wednesday detained Ruben Vardanyan -- a reported billionaire who headed the Nagorno-Karabakh government from November 2022 until February.

Baku said on Thursday it had charged Vardanyan with "financing terrorism".

The region's former foreign minister David Babayan said he had also been added to Baku's "black list" and agreed to hand himself over to Azerbaijani authorities.

Why this week's mass exodus from embattled Nagorno-Karabakh reflects decades of animosity

JIM HEINTZ

Updated Thu, September 28, 2023

Armenia AzerbaijanEthnic Armenian elderly women from Nagorno-Karabakh rest after arriving in Armenia's Goris in Syunik region, Armenia, Thursday, Sept. 28, 2023. Armenian officials say over 66,000 people — more than half of the region's population of 120,000 — has already left for Armenia.

(AP Photo/Vasily Krestyaninov)

TALLINN, Estonia (AP) — The exodus of ethnic Armenians this week from the region known as Nagorno-Karabakh has been a vivid and shocking tableau of fear and misery. Roads are jammed with cars lumbering with heavy loads, waiting for hours in traffic jams. People sit amid mounds of hastily packed luggage.

As of Thursday, more than 78,300 people had left the breakaway region for Armenia. That's a huge number — more than half of the population of the region that is located entirely within Azerbaijan.

Still, it's not the largest displacement of civilians in three decades of conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan following the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union.

After ethnic Armenian forces secured control of Nagorno-Karabakh and surrounding territories in 1994, refugee organizations estimated that some 900,000 people had fled to Azerbaijan and 300,000 to Armenia.

When war broke out again in 2020 and Azerbaijan seized more territory, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees said 90,000 had gone to Armenia and 40,000 to Azerbaijan.

Those figures underline the fierce animosity between the two countries, and they raise questions about the region’s future.

WHAT IS THE REGION?

Nagorno-Karabakh, with a population of about 120,000, is a mountainous, ethnic Armenian region inside Azerbaijan in the southern Caucasus Mountains.

When both Azerbaijan and Armenia were part of the Soviet Union, the region was designated as an autonomous republic, but as Moscow’s central control of far-flung regions deteriorated, a movement arose in Nagorno-Karabakh for incorporation into Armenia.

Tensions burst into violence in 1988 when more than 30 — some say as many as 200 — ethnic Armenians were killed in a pogrom in the Azerbaijani city of Sumgait. Armenians fled, as did many ethnic Azeris who lived in Armenia. When a full-scale war broke out, the numbers soared. That first war lasted until 1994.

Azerbaijan regained control of parts of Nagorno-Karabakh and large swaths of adjacent territory held by Armenians in a six-week war in 2020, driving out tens of thousands of Armenians that the government in Baku declared to have settled illegally.

WHAT HAPPENED IN RECENT DAYS?

Last week, Azerbaijan launched a blitz that forced the capitulation of Nagorno-Karabakh’s separatist forces and government. On Thursday, the separatist authorities agreed to disband by the end of this year.

The events put the region's ethnic Armenians on the move out of the territory.

Nagorno-Karabakh and the territory around it have deep cultural and religious significance for Christian Armenians and predominantly Muslim Azeris, and each group denounces the other for alleged efforts to destroy or desecrate monuments and relics.

Armenians were deeply angered by recent video that purportedly showed an Azerbaijani soldier firing at a monastery in the region. Azeris have seethed with resentment at Armenians’ wholesale pillaging of the once-sizable city of Aghdam and the use of its mosque as a cattle barn.

WHY HAVE THE SEPARATISTS QUICKLY GIVEN UP?

A Russian peacekeeping force of about 2,000 was deployed to Nagorno-Karabakh under an armistice that ended the 2020 war. But its inaction in the latest Azerbaijani offensive probably was a key factor in the separatists’ quick decision to give in.

In December, Azerbaijan began blocking the only road leading from Nagorno-Karabakh to Armenia.

Armenians bitterly criticized the peacekeepers for failing to follow their mandate to keep the road open. The blockade caused severe food and medicine shortages in Nagorno-Karabakh. International organizations and governments called repeatedly for Baku to lift the blockade.

Russia, which is fighting a war in Ukraine, seems to be unable or unwilling to take action to keep the road open. That appears to have persuaded the separatists that they would get no support when Azerbaijan launched its blitz.

Nagorno-Karabakh’s forces were small and poorly supplied in comparison with those of Azerbaijan, thanks to the country’s surging oil revenues and support from Turkey.

WHAT WILL THE FUTURE HOLD?

Under last week's cease-fire, Azerbaijan will “reintegrate” Nagorno-Karabakh, but the terms for that are unclear. Baku repeatedly has promised that the rights of ethnic Armenians will be observed if they stay in the region as Azerbaijani citizens.

That promise appears to have reassured almost no one. Although Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan said last week that he saw no immediate need for Armenians to leave, on Thursday he said he expected that none would be left in Nagorno-Karabakh within a few days.

Ethnic Armenians in the region do not trust Azerbaijan to treat them fairly and humanely or grant them their language, religion and culture.

Without an international peacekeeping or police force in the region, ethnic violence would be almost certain to flare.

TALLINN, Estonia (AP) — The exodus of ethnic Armenians this week from the region known as Nagorno-Karabakh has been a vivid and shocking tableau of fear and misery. Roads are jammed with cars lumbering with heavy loads, waiting for hours in traffic jams. People sit amid mounds of hastily packed luggage.

As of Thursday, more than 78,300 people had left the breakaway region for Armenia. That's a huge number — more than half of the population of the region that is located entirely within Azerbaijan.

Still, it's not the largest displacement of civilians in three decades of conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan following the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union.

After ethnic Armenian forces secured control of Nagorno-Karabakh and surrounding territories in 1994, refugee organizations estimated that some 900,000 people had fled to Azerbaijan and 300,000 to Armenia.

When war broke out again in 2020 and Azerbaijan seized more territory, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees said 90,000 had gone to Armenia and 40,000 to Azerbaijan.

Those figures underline the fierce animosity between the two countries, and they raise questions about the region’s future.

WHAT IS THE REGION?

Nagorno-Karabakh, with a population of about 120,000, is a mountainous, ethnic Armenian region inside Azerbaijan in the southern Caucasus Mountains.

When both Azerbaijan and Armenia were part of the Soviet Union, the region was designated as an autonomous republic, but as Moscow’s central control of far-flung regions deteriorated, a movement arose in Nagorno-Karabakh for incorporation into Armenia.

Tensions burst into violence in 1988 when more than 30 — some say as many as 200 — ethnic Armenians were killed in a pogrom in the Azerbaijani city of Sumgait. Armenians fled, as did many ethnic Azeris who lived in Armenia. When a full-scale war broke out, the numbers soared. That first war lasted until 1994.

Azerbaijan regained control of parts of Nagorno-Karabakh and large swaths of adjacent territory held by Armenians in a six-week war in 2020, driving out tens of thousands of Armenians that the government in Baku declared to have settled illegally.

WHAT HAPPENED IN RECENT DAYS?

Last week, Azerbaijan launched a blitz that forced the capitulation of Nagorno-Karabakh’s separatist forces and government. On Thursday, the separatist authorities agreed to disband by the end of this year.

The events put the region's ethnic Armenians on the move out of the territory.

Nagorno-Karabakh and the territory around it have deep cultural and religious significance for Christian Armenians and predominantly Muslim Azeris, and each group denounces the other for alleged efforts to destroy or desecrate monuments and relics.

Armenians were deeply angered by recent video that purportedly showed an Azerbaijani soldier firing at a monastery in the region. Azeris have seethed with resentment at Armenians’ wholesale pillaging of the once-sizable city of Aghdam and the use of its mosque as a cattle barn.

WHY HAVE THE SEPARATISTS QUICKLY GIVEN UP?

A Russian peacekeeping force of about 2,000 was deployed to Nagorno-Karabakh under an armistice that ended the 2020 war. But its inaction in the latest Azerbaijani offensive probably was a key factor in the separatists’ quick decision to give in.

In December, Azerbaijan began blocking the only road leading from Nagorno-Karabakh to Armenia.

Armenians bitterly criticized the peacekeepers for failing to follow their mandate to keep the road open. The blockade caused severe food and medicine shortages in Nagorno-Karabakh. International organizations and governments called repeatedly for Baku to lift the blockade.

Russia, which is fighting a war in Ukraine, seems to be unable or unwilling to take action to keep the road open. That appears to have persuaded the separatists that they would get no support when Azerbaijan launched its blitz.

Nagorno-Karabakh’s forces were small and poorly supplied in comparison with those of Azerbaijan, thanks to the country’s surging oil revenues and support from Turkey.

WHAT WILL THE FUTURE HOLD?

Under last week's cease-fire, Azerbaijan will “reintegrate” Nagorno-Karabakh, but the terms for that are unclear. Baku repeatedly has promised that the rights of ethnic Armenians will be observed if they stay in the region as Azerbaijani citizens.

That promise appears to have reassured almost no one. Although Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan said last week that he saw no immediate need for Armenians to leave, on Thursday he said he expected that none would be left in Nagorno-Karabakh within a few days.

Ethnic Armenians in the region do not trust Azerbaijan to treat them fairly and humanely or grant them their language, religion and culture.

Without an international peacekeeping or police force in the region, ethnic violence would be almost certain to flare.

Exodus and ethnic cleansing? The sudden end of a decades long dream in the Caucasus

Matt Bradley and Natasha Lebedeva

Thu, September 28, 2023

Nagorno-Karabakh to dissolve after years-long war with Azerbaijan ends

After years of conflict, the war between Nagorno-Karabakh and Azerbaijan has finally ended. The contested region now falls under Azerbaijani control as tens of thousands of ethnic Armenians flee their homeland. NBC News’ Matt Bradley reports.

After more than half the population of an ethnic Armenian enclave fled their homes in a mountainous pocket of land south of Russia, the breakaway republic’s leaders said it would soon “cease to exist.”

In what amounted to a formal capitulation to Azerbaijan, which surrounds it, the Armenian leaders of Nagorno-Karabakh said the self-declared Republic of Artsakh would be dismantled by the end of the year.

This would end three decades of intermittent conflict in and around the enclave, break a 10-month blockade of the region in the South Caucasus that residents said had starved them into submission, and dash hopes of an independent state in territory claimed by Azerbaijan.

The dissolution of Nagorno-Karabakh as a breakaway state is a seminal point — a rare supernova among the constellation of ethnic conflicts left by the implosion of the then-Soviet Union in the early 1990s. The conflict’s abrupt halt reflects how the geopolitical reach of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has forced realignments far beyond that war.

In an official decree, the region’s separatist President Samvel Shakhramanyan said that residents of Nagorno-Karabakh must now “familiarize themselves with the conditions of reintegration” into Azerbaijan and make “an independent and individual decision about the possibility of staying (or returning) in Nagorno-Karabakh.”

The announcement came as around 70,000 of the enclave’s population of about 120,000 fled from the region, which sits within Azerbaijan’s borders, to neighboring Armenia, according to Armenia’s government, with more still arriving.

Many residents hauled what few personal belongings they could gather into packed cars, trucks, buses and tractors, some pockmarked with shrapnel after days of Azerbaijani attacks.

Armenia’s leadership has accused Azerbaijan of instigating a refugee crisis by launching a swift invasion this week. Azerbaijan has denied allegations of “ethnic cleansing,” saying it is not forcing people to leave, and would peacefully reintegrate the region and guarantee rights of ethnic Armenians.

Holding a wealth of monasteries, mosques and other religious sites, Nagorno-Karabakh is culturally significant for both Muslim Azeris and what was an overwhelming Christian Armenian population. Armenians in Azerbaijan have been victims of pogroms, while Azerbaijanis claim discrimination and violence at the hands of Armenians.

“Azerbaijan has won a comprehensive military victory and what we’re looking at now is the prospect of Nagorno-Karabakh without Armenians or with very few Armenians remaining,” said Thomas de Waal, a senior fellow with the London-based Carnegie Europe think tank. “So in that sense, Azerbaijan has won.”

For those fleeing, the despair of losing their homes was made worse by losing their homeland.

“Many of them are from villages which were taken by the Azerbaijani army, so they really lost their homes already,” said Astrig Agopian, a French Armenian journalist who has been reporting this week on the refugee crisis from Armenia’s border. “There is really this feeling that this time is different. It’s another war, but it’s a war that is definitely lost this time.”

Were that the case, it would bring to an end decades of violence in the region, which has been at the center of geopolitical interests between Eastern and Western nations for centuries.

The political dispute between Armenia and Azerbaijan over Nagorno-Karabakh began as the then-Soviet Union weakened in the late 1980s, and Armenians demanded that the majority-Armenian region be incorporated into the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic.

After the USSR collapsed in 1991, the conflict erupted into a full-scale war that persisted until a Russian-brokered peace deal in 1994. About 30,000 people were killed and more than a million people displaced.

“My husband died in the first war. He was 30, I was 26. Our children were 3 and 4 years old. It is the fourth war that I went through,” Narine Shakaryan, a grandmother of four, told the Reuters news agency after she arrived in Armenia. “My husband died back then, he was 30 in 1994. That’s the cursed life that we live.”

The fighting continued intermittently for several more decades, leaving an indelible mark on generations of Nagorno-Karabakh’s ethnic Armenian residents. A recent war in 2020 saw the more powerful Azerbaijan, backed by Turkey, reclaim much of the land surrounding the area, as well as part of the region itself.

Russia negotiated an end to that flare-up and even deployed peacekeepers to ensure security along the Lachin Corridor, the single mountain road that connected Armenia to Nagorno-Karabakh.

But the events of the past year show how Moscow, which has historically played the role of both peacekeeper and ally to Armenia — which shares its Christian roots and hosts a Russian military base — has adjusted its allegiances following its invasion of Ukraine and its conflicts with the West.

“The pivotal factor was that Azerbaijan was talking separately to the Russians, and had a joint agenda with the Russians, to pressure Armenia and also to keep the West out of the Caucasus,” de Waal said. “This is why when the Azerbaijani assault happened, Russian peacekeepers who could have actually stopped it stood down. And then Russia failed to condemn the attack.”

After its invasion of Ukraine left Russia isolated, Moscow may feel it has more to gain from cozying up to Azerbaijan than Armenia, particularly after the latter made a public display of cozying up to the West and provided humanitarian aid to Kyiv.

Earlier this month, the country conducted joint exercises with the U.S. military and the Armenian Parliament is set to vote next week on whether to accede to the International Criminal Court, which classifies Russian President Vladimir Putin as a war criminal — a move the Kremlin characterized Thursday as “extremely hostile.”

Inside Nagorno-Karabakh, Azerbaijan’s government has assured the region’s Armenian population that they will be treated humanely and afforded equal rights.

But after months of blockades and blistering fighting, few ethnic Armenians believe it and many feel they have no choice but to flee.

This article was originally published on NBCNews.com

Armenians in Russia return home to help Karabakh refugees

Felix Light

Wed, September 27, 2023

Refugees from Nagorno-Karabakh arrive in Kornidzor

KORNIDZOR, Armenia (Reuters) - When Azerbaijan overran the breakaway region of Nagorno-Karabakh, David Harapetyan drove 1,000 km (620 miles) from his home in the Russian city of Stavropol to this Armenian border village to help fleeing Karabakh Armenians.

The 36-year-old taxi driver on Wednesday was handing out food, water and cigarettes to refugees arriving in Armenia after spending 10 months under an Azerbaijani blockade that led to critical shortages in Karabakh.

"I came here from Stavropol when I saw what is happening here. I came to help my people however I can," said Harapetyan, who was born in this southern corner of Armenia but holds only Russian citizenship.

Russia is home to the world's largest Armenian diaspora. The United States and France also have large ethnic Armenian communities.

Armenia’s government said on Wednesday that more than 50,000 Karabakh refugees so far had crossed the border, out of a total estimated Karabakh Armenian population of 120,000.

The sudden influx has strained resources in Goris, the border town where Armenian authorities have booked out hotels for refugees with nowhere to go.

Harapetyan said he and a group of 10 Stavropol Armenians he had arrived with were helping new arrivals with accommodation.

"We arrived and even found houses where we can accommodate some people who have no home."

Among those helped by Harapetyan were 49 men, women and children who arrived crammed into Karen Martirosyan’s KAMAZ truck.

Martirosyan, 39, a soldier in Karabakh’s defeated army, had driven from the frontline village of Badara in his truck.

BREAKDOWNS

During the 77 km (48 mile) drive from Stepanakert, the capital of Karabakh, which took two days due to heavy traffic, he picked up stragglers whose truck had broken down.

"Their KAMAZ broke down on the road late at night," said Martirosyan, whose own overloaded truck was also towing a car carrying five more people who had run out of fuel.

"They were out in the open. So I took them with me and came here - 43 (people) in the back, and five more in the cabin."

As volunteers at the border gave out food and water to the 20 or so children on board, an old woman shouted from the truck that she blamed Armenian and Karabakh leaders, past and present, for the loss of her homeland.

"All of Karabakh has been taken hostage by Azerbaijan! That's it! It's all our president's fault! He did all of it, he is the one responsible!"

(Writing by Gareth Jones, Editing by William Maclean)

No comments:

Post a Comment